Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi: The Making of the Mahatma in South Africa

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 28 Mar 2022

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

The Cutting, Faceting and Polishing of a Diamond

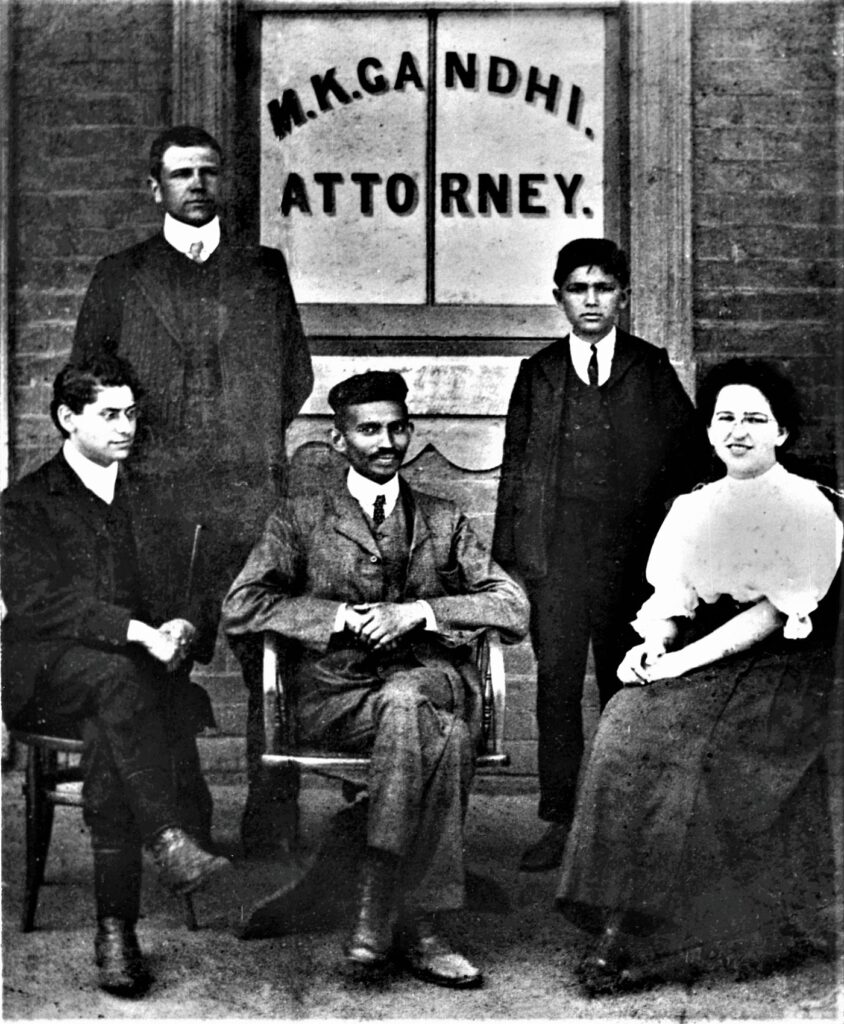

London trained Barrister: Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (center) sits with co-workers at his Johannesburg law office in South Africa, 1902, before his transformation into The Mahatma.

There were the usual supporters and followers of The Mahatma who were making their way to the grounds of Birla House in Delhi on Friday, 30th January 1948, to participate in the evening prayers which the Gandhiji was attending. In the crowd was Nathuram Godse, an ultra-Hindu nationalist, who was a member of the Hindu Maha Sabha, a right-wing, religio-political fundamentalist party, who felt that Gandhiji was too sympathetic towards to minority Muslim population of India. This party justifiably were of an opinion that the Hindus were persecuted during the rule of the Mughal dynasty, of India, and over this era developed deep seated acrimony towards the Muslims, who were really converted Hindus. As Nathuram Godse edged his way towards the asthenic figure of the Mahatma, his hand went into his pocket and felt the cold steel of the Italian-made, automatic pistol No. 719791, Beretta CAL 9, manufactured in 1934. It is believed that the pistol changed many hands in Gwalior, until it finally came in possession of Jagdish Prasad Goel who passed it on to Gangadhar Dandavate who finally delivered it to Nathuram Godse. The question regarding ownership of the pistol has been the subject of great controversy and aggressive debate. Prior to this fateful day, the Mahatma, was perpetually fasting for 21 days[1], with total starvation, except water, to end the horrific massacres of the sectarian violence, including rape, of women and girls, between Hindus and Muslims, around The Partition of the Indian Peninsula. This was specifically designed and executed by the departing British Raj, after nearly 200 years of oppressive rule and exploitation of India. This divide and rule policy was the British trademark, as final punishment for the Indian resistance eventually leading to the bloody Indian independence scenario in 1947-1948. “Bapujee”, “the Father of the Nation” , as the Mahatma was lovingly known in India, was highly respected, by both Hindus as well as Muslims and he was totally against the division of India along religious lines, a bad British legacy, which even in the 21st century is the cause of great acrimony and hatred amongst the two major religious groups in India.

Nathuram Godse was finally facing the Great Soul, as he pulled out the Beretta and fired three shots, at point blank range, into the thin chest of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. The crowd was stunned into silence as Gandhi collapsed to the ground. Gandhi took half an hour to expire from the mortal bullet wounds. It is most surprising that no efforts were made to seek medical attention for the seriously wounded Gandhiji during that eternally long half an hour. However, the Great Soul surrounded by his apparently, single assassin and a multitude of followers, expired peacefully, forgiving the man who killed by uttering “Oh Ram”, thus ending his 74 years of healthy, fit, illustrious life, fighting for justice against racial oppression by the British, utilising his trademark peaceful, non-violence resistance mechanism of Ahimsa.[2] The great love that the entire population of India had for Gandhi, be it Sikhs, Hindus, Muslims, Christians and other religious denominations, was clearly demonstrated by the immediate cessation of the serious violence and killings on both side during the mass migrations of Hindus and Muslims to the newly formed states of Pakistan and India.

Nathuram Godse killed Mahatma Gandhi with the infamous Beretta, was arranged by the Gwalior doctor Dattatreya Parchure, who is believed to have founded the Hindu Rashtra Sena (HRS), party. According to Suresh[3], in the book, he tries to analyse which Gandhi was assassinated:

- The anti-national, anti-colonial protagonist of equality for all and the champion of the poor. in the caste dominated, hierarchical society of India, in the immediate post- independence period in1948.

- Or alternatively, the apostle of non-violence and the promulgator of the peaceful resistance against the British Empire and its colonial regimes, the one for whom God was love, not Rama, not Allah, which eventually led to the independence of India.

The authors say that Godse and those whom he represented killed a Gandhi they completely misunderstood. “Or perhaps they never had the ethical sensibility and the spiritual imagination that are necessary to understand him in the first place,” they write.

While Gandhi is always associated with the passive resistance “fight” for the Independence of India, as the thin, Indian, dressed in loincloth and energetically walking the equivalent of twice round the world, in sandals, as estimated by one source, with his traditional stick, what most do not know that he spent 21 years of his early formative life in South Africa. as a London trained Barrister.

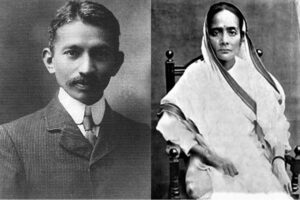

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on 2nd October 1869 into a Gujarati Hindu Bania family[4] of the Vaishya varna in Porbandar, also known as Sudamapuri, a coastal town on the Kathiawar Peninsula and then part of the small princely state of Porbandar in the Kathiawar Agency of the Indian Empire, the capital of a small principality in what is today the state of Gujarat in Western India. His mother was a profoundly religious Hindu. His father, Karamchand Uttamchand Gandhi (1822–1885), served as the Diwan, the chief Minister of Porbandar state.[5] There is a paucity of records of Gandhi’s early life. In May 1883, 14-year-old Gandhi was married to 13-year-old Kasturbai Gokuldas Kapadia, who was born on 1th 1 April 1869 to Gokuladas Kapadia and Vrajkunwerba Kapadia. The marriage was arranged by their parents. Arranged marriages being commonplace and traditional in India.[6] They were married for a total of sixty-two years.[7] Recalling the day of their marriage, her husband once said, “As we didn’t know much about, for us it meant only wearing new clothes, eating sweets and playing with relatives.” However, as was prevailing tradition, the adolescent bride was to spend the first few years of marriage , until old enough to cohabit with her husband, at her parents’ house, and away from her husband.[8] Writing many years later, Mohandas described with regret the lustful feelings he felt for his young bride, “even at school I used to think of her, and the thought of nightfall and our subsequent meeting was ever haunting me.”[9] At the beginning of their marriage, Mohandas was also possessive and manipulative; he wanted the ideal wife who would follow his command.[10] In 1896 she and their two sons went to live with him in South Africa.[11]

In April 1893, Gandhi aged 23, set sail for South Africa to be the lawyer[12] for Abdullah’s cousin,[13] to fight Dadabhai Abdulla’s case.[14] It was a long journey from India to South Africa. Gandhi reached the port of Natal towards the end of May, 1893. This Indian businessman admired him for his fluency in English, legal matters and Gujarati background.[15] The first thing he noticed was that the Indians there were treated with little respect. Within a week of his arrival in Durban, he visited the court with Abdulla Seth of Dada, Abdulla &Co. No sooner Gandhi had sat down, the magistrate pointed his plump finger at him. ‘You must remove your turban,’ he said sternly. Gandhi was surprised. He looked round and saw several Mohammedans and Parsees wearing turbans.[16] He could not understand why he was singled out to be rebuked. ‘Sir,’ he replied, ‘I see no reason why I should remove my turban. I refuse to do so.’ ‘You will please remove it,’ the magistrate roared. At this Gandhi left the court.

Abdulla ran after him into the corridor and caught his arm. ‘You don’t understand,’ he said. ‘I will explain why these white-skinned people behave like this.’ Abdulla continued: ‘They consider Indians inferior and address them as ‘coolie’ or sami’. Parsees and Mohammedans are permitted to wear turbans as their dress is thought to be of religious significance.’ Gandhi’s dark eyes flashed with anger. ‘The magistrate insulted me, ‘he said. ‘Any such rule is an insult to a free man. I shall write at once to the Durban press to protest against such insulting rules.’ However, Gandhi did write. The letter was published and it received unexpected publicity. However, some papers describe Gandhi as an ‘unwelcome visitor’.[17]

However, Gandhi did not serve only those rich businessmen. Albeit, the success of this case won Gandhi great respect with the local Indian community and resulted in him have a large number of retainers from local, Indian businessmen in Durban. He also fought cases for indentured laborer, mainly permit renewal type litigations. Interestingly, he was the only Indian barrister practicing in Natal. Hence very busy with work. He spent 21 years in South Africa, where he developed his political views[18], ethics and politics.[19] Immediately upon arriving in South Africa, Gandhi faced discrimination because of his skin colour and heritage, like all people of colour.[20] He was not allowed to sit with European passengers in the stagecoach and told to sit on the floor near the driver, then beaten when he refused; elsewhere he was kicked into a gutter for daring to walk near a house.

In another racial incident, Gandhi thrown off a train at Pietermaritzburg[21] after refusing to leave the first-class compartment, for which he paid appropriately.[22] After a week in Durban, he left for Pretoria to attend to the case for which he had been engaged. With a first-class ticket he boarded the train. At the next stop an Englishman got into his compartment. He looked at a Gandhi with contempt, called the conductor, and said: ‘Take this coolie out and put him in the place where he belongs. I will not travel with a coloured man.’ ‘Yes, sir,’ said the conductor. He then turned to Gandhi. ‘Hey sami,’ he said, ‘come along with me to the next compartment.’ ‘No, I will not,’ said Gandhi calmly. ‘I was sold a first-class ticket and I have every right to be here.’ A constable was called in and he pushed Gandhi out with bag and baggage. The train steamed away leaving him on the platform. He spent the night shivering in the dark waiting-room. Gandhi took this experience to heart and resolved that, whatever the cost might be, he would fight all such injustices. He sent a note of protest to the General Manager of the railway, but the official justified the conduct of his men. He sat in the train station, shivering all night and pondering if he should return to India or protest for his rights.[23] He chose to protest and was allowed to board the train the next day.[24] Indians were not allowed to walk on public footpaths in South Africa. Gandhi was kicked by a police officer out of the footpath onto the street without warning.[25] When Gandhi arrived in South Africa, according to Herman, he thought of himself as “a Briton first, and an Indian second”.[26] However, the prejudice against him and his fellow Indians from British people that Gandhi experienced and observed deeply bothered him. He found it humiliating, struggling to understand how some people can feel honour or superiority or pleasure in such inhumane practices.[27] Gandhi began to question his people’s standing in the British Empire.[28]

Originally, Gandhi only planned to stay in South Africa for one year, however, after witnessing the racial segregation, discrimination, and systematic oppression that South African Indians were forced to deal with, he decided to stay. Furthermore, his personal humiliating experience of being expelled from a “whites only” train, despite the fact that he paid for a first class ticket, and the subsequent trail, in which he was forced to remove is turban, spurred his inner determination to stay in South Africa and help his fellow Indians. The 21 years that Gandhi spent in South Africa before returning to India and fighting for their liberation from British rule were monumental. It was during these 21 years that he started a movement towards non-violence and peaceful resistance that would impact future great leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Nelson Mandela.[29]

The Abdullah case that had brought him to South Africa concluded in May 1894, and the Indian community organised a farewell party for Gandhi as he prepared to return to India.[30] However, a new Natal government discriminatory proposal led to Gandhi extending his original period of stay in South Africa. He planned to assist Indians in opposing a bill to deny them the right to vote, a right then proposed to be an exclusive European right. He asked Joseph Chamberlain, the British Colonial Secretary, to reconsider his position on this bill.[31] Though unable to halt the bill’s passage, his campaign was successful in drawing attention to the grievances of Indians in South Africa. He helped found the Natal Indian Congress in 1894,[32] and through this organisation, he moulded the Indian community of South Africa into a unified political force. In January 1897, when Gandhi landed in Durban, a mob of white settlers attacked him[33] and he escaped only through the efforts of the wife of the police superintendent. However, he refused to press charges against any member of the mob.[34]

During the Boer War, Gandhi volunteered in 1900 to form a group of stretcher-bearers as the Natal Indian Ambulance Corps. According to Arthur Herman, Gandhi wanted to disprove the British colonial stereotype that Hindus were not fit for “manly” activities involving danger and exertion, unlike the Muslim “martial races”.[35] Gandhi raised eleven hundred Indian volunteers, to support British combat troops against the Boers. They were trained and medically certified to serve on the front lines. They were auxiliaries at the Battle of Colenso to a White volunteer ambulance corps. At the battle of Spion Kop Gandhi and his bearers moved to the front line and had to carry wounded soldiers for miles to a field hospital because the terrain was too rough for the ambulances. Gandhi and thirty-seven other Indians received the Queen’s South Africa Medal.[36]

Gandhi with stretcher bearers if the Indian Ambulance Corps during the Anglo Boer War in South Africa

In August 1906, the British administration in the Transvaal passed the Asiatic Law Amendment Ordinance (Black Act) to control the entry of Indians into the Transvaal. Every Indian man, woman and child older than 8 years had to register with the Registrar of Asiatics. Indians and Chinese who did not register by a certain date would no longer be allowed to stay in the Transvaal. The law required Indian people to have their fingerprints taken in order to be issued with their registration certificates. The certificate had to be carried at all times and be produced on demand to any policeman who asked to see them. An Indian who could not produce a certificate could be fined and sent to prison. Gandhi moved to the Transvaal and set up an office in Johannesburg. He wasted no time in mounting a campaign to oppose the new law.

Gandhi contacted Leung Quinn, the leader of the Chinese community, to discuss the Black Act as it applied to that community too. The majority of the Chinese people in South Africa were brought as indentured labourers to work on the Transvaal gold mines.

Within a few days, on 11th September, thousands of Indians and Chinese attended the meeting held at the Empire Theatre and vowed not to submit to the Black Act, no matter what the consequences and the government’s threats. This vow came to be later known as the Satyagraha Oath, and it marked the beginning of the eight-year-long Satyagraha Campaign and the Birth of the Satyagraha movement. Smuts did not repeal the Black Act as he had promised. His breaking of the agreement angered the Indian community and Gandhi sent a letter to Parliament, reminding Smuts of the terms of their agreement. In the letter, Gandhi warned that if Smuts did not repeal the Act as promised the Indians would burn their registration certificates. By the closing date of registration in terms of the Black Act, only 511 Indians had registered out of the total Indian population of over 13 000 in the Transvaal. Gandhi gave Smuts until 16th August 1908 to respond. On this day, the Indian community held a meeting on the grounds of the Hamidia Mosque in Johannesburg. A three-legged pot stood in the corner of the grounds, waiting to be used to burn the registration certificates, if necessary. A telegram arrived from Smuts, saying that the government could not agree to the request of the community.

The certificates were burnt and the Satyagraha Campaign started again. The newspapers gave vivid descriptions of the bonfire, in which more than 2 000 certificates were burnt.[37] Gandhi adopted his still evolving methodology of Satyagraha, devotion to the truth, or nonviolent protest, for the first time.[38] According to Anthony Parel, Gandhi was also influenced by the Tamil moral text Tirukkuṛaḷ after Leo Tolstoy[39] mentioned it in their correspondence that began with “A Letter to a Hindu”.[40] Gandhi urged Indians to defy the new law and to suffer the punishments for doing so. Gandhi’s ideas of protests, persuasion skills and public relations had emerged. He took these skills, acquired while in South Africa, to India, upon his return in 1915.[41],[42]

Gandhi focused his attention on Indians while in South Africa. He initially was not interested in politics. This changed, however, after he was discriminated against and bullied, such as by being thrown out of a train coach because of his skin colour by a white train official. After several such incidents with Whites in South Africa, Gandhi’s thinking and focus changed, and he felt he must resist this and fight for rights. He entered politics by forming the Natal Indian Congress.[43] According to Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed, Gandhi’s views on racism are contentious, and in some cases, distressing to those who admire him. Gandhi suffered persecution from the beginning in South Africa. Like with other coloured people, white officials denied him his rights, and the press and those in the streets bullied and called him a “parasite”, “semi-barbarous”, “canker”, “squalid coolie”, “yellow man”, and other epithets. People would spit on him as an expression of racial hate.[44]

While in South Africa, Gandhi focused on racial persecution of Indians but ignored those of Africans. In some cases, state Desai and Vahed, his behaviour was one of being a willing part of racial stereotyping and African exploitation.[45] During a speech in September 1896, Gandhi complained that the whites in the British colony of South Africa were degrading Indian Hindus and Muslims to “a level of Kaffir”.[46] Scholars cite it as an example of evidence that Gandhi at that time thought of Indians and black South Africans differently. As another example given by Herman, Gandhi, at age 24, prepared a legal brief for the Natal Assembly in 1895, seeking voting rights for Indians. Gandhi cited race history and European Orientalists’ opinions that “Anglo-Saxons and Indians are sprung from the same Aryan stock or rather the Indo-European peoples”, and argued that Indians should not be grouped with the Africans.[47]

Years later, Gandhi and his colleagues served and helped Africans as nurses and by opposing racism, according to the Nobel Peace Prize winner Nelson Mandela. The general image of Gandhi, state Desai and Vahed, has been reinvented since his assassination as if he was always a saint when in reality his life was more complex, contained inconvenient truths and was one that evolved over time.[48] In contrast, other Africa scholars state the evidence points to a rich history of co-operation and efforts by Gandhi and Indian people with non-white South Africans against persecution of Africans and the Apartheid.[49]

In 1906, when the Bambatha Rebellion broke out in the colony of Natal, then 36-year old Gandhi, despite sympathising with the Zulu rebels encouraged Indian South Africans to form a volunteer stretcher-bearer unit.[50] Writing in the Indian Opinion, Gandhi argued that military service would be beneficial to the Indian community and claimed it would give them “health and happiness.”[51] Gandhi eventually led a volunteer mixed unit of Indian and African stretcher-bearers to treat wounded combatants during the suppression of the rebellion.[52]

The medical unit commanded by Gandhi operated for less than two months before being disbanded.[53] After the suppression of the rebellion, the colonial establishment showed no interest in extending to the Indian community the civil rights granted to white South Africans. This led Gandhi to becoming disillusioned with the Empire and aroused a spiritual awakening with him; historian Arthur L. Herman wrote that his African experience was a part of his great disillusionment with the West, transforming him into an “uncompromising non-cooperator”.[54]

The specific birth place of Gandhi’s non-violent ideas was the Phoenix settlement. The Phoenix settlement was originally established by Gandhi in 1904 to provide a location for him to found the Natal Indian Congress (NIC), teach others basic survival skills such as cloth weaving and farming, print his newspaper called The Indian Opinion, and lead others in prayer and studies of social justice, peace, and harmony. Moreover, in the future, the Phoenix settlement would serve as the site of Gandhi work camps which were started in 1967 to educate South Africans about unity and togetherness and the first meeting of the United Democratic Front (UDF) which was an organisation against Apartheid. Additionally, Gandhi’s newspaper, The Indian Opinion, would expand to provide a voice for all South Africans and their various viewpoints. On Friday, August 9, 1985 the settlement was destroyed and it was not reopened to honour Gandhi’s work until 2000. However, Gandhi’s teachings of the Gandhian Trinity, developed while in South Africa, were never forgotten.

The Gandhian Trinity consists of Satygraha (truth force), Ahimsa (non-killing and non-violence), and Savrodaya (the welfare of all). Gandhi used these principles to help struggling mine and sugar-cane field workers gain rights, liberate women from cultural oppression, and fight social injustices and evils. He truly believed that these principles, especially that of non-violence, was the only way to fight against wrongs because “an eye for an eye will leave the world blind.” In other words, he believed that fighting violence with violence would only beget more violence and that it takes a much stronger man to look his oppressor in the eyes and do nothing as he beats him mercilessly. Furthermore, it was these principles that inspired Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Nelson Mandela to use peaceful non-violence to end legal racial segregation and liberate South Africa and the United States of America from social oppression and injustice.[55] The ideas created at the Phoenix settlement and his personal experiences with racial discrimination, Gandhi’s presence in Durban was a pivotal moment in the history of non-violent movements for social inequality. Moreover, the reconstruction of the Phoenix settlement to commemorate Gandhi and his work in South Africa demonstrates the remarkable changes that have taken place post-Apartheid and the magnanimous influence that Gandhi has had on the world and future scholars.[56]

In 1910, Gandhi established, with the help of his friend Hermann Kallenbach, an idealistic community they named Tolstoy Farm near Johannesburg.[57] There he nurtured his policy of peaceful resistance.[58]

In the years after black South Africans gained the right to vote in South Africa (1994), Gandhi was proclaimed a national hero with numerous monuments.[59]

The Bottom Line is that Mahatma was an Indian lawyer,[60] anti-colonial nationalist[61] and political ethicist[62] who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India’s independence from British rule,[63] and to later inspire movements for civil rights and freedom across the world. The honorific Mahatma[64], Sanskrit: “great-souled”, “venerable”, first applied to him in 1914 in South Africa,[65] is now used throughout the world. Mahatma Gandhi was the leader of India’s non-violent independence movement against British rule and in South Africa who advocated for the civil rights of Indians, who were first brought into South Africa as Indentured labourers [66] by the British to work as “slaves” on sugar cane plantations. Between the years 1860 and 1911, 152 184 persons of Indian origins were introduced as indentured labour force into South Africa, the last batch having arrived on the S.S. Umlazi on 21st July 1911. The subsequent batch of Indian migrants were free Indians, who came to South Africa as business entrepreneurs, professionals such as educationist, craftsmen, jewelers and lawyers such a Gandhi, vernacular teachers such as Pundits, Brahmins, Moulanas and Alims, This was the beginning of the so called “Indian Problem” in South Africa, resulting in official racial discrimination and promulgation of legal apartheid acts officially into the legislature of the country, from 1948 until liberation in 1994. This was what Barrister Gandhi was exposed to when he came from India and what he personally experienced in terms of a second-class humanoid, compared to the Whites, who were officially classified as superior with special privileges afforded to them in South Africa. This appalled Gandhi and sowed the seeds of political activism leading up to his transformation into the Mahatma, both mentally, as well as physically, upon his return to India.

Furthermore, an important point to note as was with Tolstoy, The Mahatma received nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize, five times: 1937, 1938, 1939, 1947, and 1948. Under the rules governing the award of the Nobel Peace Prize, there was nothing to preclude the posthumous conferral of the award, though the Norwegian Nobel Committee’s own deliberations appear to have muddled the issue. On 30th January 1948, Gandhi was assassinated by Nathuram Godse; that year, six nominations were received on Gandhi’s behalf. On 18th November, the Nobel Committee, in a public pronouncement, declared that it had found “no suitable living candidate” for the award, thereby implying that that it was not empowered to confer posthumous awards.[67] However, Gandhi has never won the Nobel Prize. This singular omission, probably based on racial discrimination and not wanting to displease the British Master at the time, has been publicly regretted by later members of the Nobel Committee. It is interesting to note that when Dalai Lama was awarded the Peace Prize in 1989, the chairman of the committee said it was “in part a tribute to the memory of Mahatma Gandhi.[68] While the committee considered a posthumous award after his assassination, the explanation was that “Gandhi did not belong to an organisation, he left no property behind, and no will. So, who should receive the Prize money”? The Nobel Peace Prize committee rarely concedes a mistake, eventually acknowledged that not awarding Gandhi was an omission.[69] Let history, as viewed by the affected people, not the victorious, be the judge of these decisions made by the Nobel Committee.

Mahatma Gandhi, as he is known by his followers with reverence, preached the philosophy of non-violence which has become even more relevant today. His commitment to non-violence and satyagraha gave hope to marginalised sections of India.[70] Rajmohan Gandhi, while remembering his grandfather, said “his ideals and principles are much-needed in India nowadays where intolerance rules the roost.”[71]

The physical legacy of The Mahatma: A pair of sandals from the 1920s which were given to a friend by Gandhi auctioned for £19,000, £9,000 more than their asking price

References:

[1] https://www.wovo.org/how-long-did-gandhi-live-without-food/?msclkid=a2b8ac17aca811ec89ba06975c00cbd5

[2] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=1ef8ced04b0a5d7317c36298e0a1168c02c24c5764048247b819f9dee77e5e6aJmltdHM9MTY0ODI2MDY5NCZpZ3VpZD1mMjc1MGM3NS0wZWY0LTQ5YTQtYjZmMS0wNWNmYmEyYWIzZGEmaW5zaWQ9NTE0Nw&ptn=3&fclid=0f3397d1-acaa-11ec-a54d-2c5597e2da48&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvQWhpbXNhP21zY2xraWQ9MGYzMzk3ZDFhY2FhMTFlY2E1NGQyYzU1OTdlMmRhNDg&ntb=1

[3] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/india/beretta-gun-gwalior-link-and-gandhis-assassination/articleshow/86679050.cms

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#CITEREFRajmohan2006

[5] Gandhi, Mohandas K. (2009). An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments With Truth. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-77541-405-6.

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kasturba_Gandhi?msclkid=f11b349dacd811ec9fba97ef84999a6b#:~:text=Mohanty%2C%20Rekha%20(2011).%20%22From%20Satya%20to%20Sadbhavna%22%20(PDF).%20Orissa%20Review%20(January%202011)%3A%2045%E2%80%9349.

[7] Tarlo, Emma (1997). “Married to the Mahatma: The Predicament of Kasturba Gandhi”. Women: A Cultural Review. 8 (3): 264–277. doi:10.1080/09574049708578316.

[8]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kasturba_Gandhi?msclkid=f11b349dacd811ec9fba97ef84999a6b#:~:text=Gandhi%20(1940).%20Chapter%20%22Playing%20the%20Husband%22%20Archived%201%20July%202012%20at%20the%20Wayback%20Machine.

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kasturba_Gandhi?msclkid=f11b349dacd811ec9fba97ef84999a6b#:~:text=Gandhi%20before%20India.%20Vintage%20Books.%204%20April%202015.%20pp.%C2%A028%E2%80%9329.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D0%2D385%2D53230%2D3.

[10] Tarlo, Emma (1997). “Married to the Mahatma: The Predicament of Kasturba Gandhi”. Women: A Cultural Review. 8 (3): 264–277. doi:10.1080/09574049708578316.

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kasturba_Gandhi?msclkid=f11b349dacd811ec9fba97ef84999a6b#:~:text=In%201896%20she%20and%20their%20two%20sons%20went%20to%20live%20with%20him%20in%20South%20Africa.

[12] Giliomee, Hermann & Mbenga, Bernard (2007). “3”. In Roxanne Reid (ed.). New History of South Africa (1st ed.). Tafelberg. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-624-04359-1.

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#Herman2008

[14] https://mrunal.org/2014/04/world-history-gandhi-south-africa-transvaal-march-zulu-war-boer-war-civil-rights-movement.html?msclkid=9f5cb7b6acd211ec844ea021125089ea#:~:text=Gandhi%20Arrives%20in,busy%20with%20work.

[15] https://gandhiking.ning.com/profiles/blogs/dada-abdulla-and-mahatma-gandhi-1

[16] http://wikilivres.ca/wiki/The_Story_of_My_Experiments_with_Truth/Part_II/Some_Experiences

[17] https://www.mkgandhi.org/storyofg/chap05.htm#:~:text=The%20first%20thing,an%20%27unwelcome%20visitor%27.

[18] Into that Heaven of Freedom: The impact of apartheid on an Indian family’s diasporic history”, Mohamed M Keshavjee, 2015, by Mawenzi House Publishers, Ltd., Toronto, ON, Canada, ISBN 978-1-927494-27-1

[19] Power, Paul F. (1969). “Gandhi in South Africa”. The Journal of Modern African Studies. 7 (3): 441–55. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00018590. JSTOR 159062.

[20] Parekh, Bhikhu C. (2001). Gandhi: a very short introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-285457-5.

[21] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#:~:text=S.%20Dhiman%20(2016).%20Gandhi%20and%20Leadership%3A%20New%20Horizons%20in%20Exemplary%20Leadership.%20Springer.%20pp.%C2%A025%E2%80%9327.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D1%2D137%2D49235%2D7.

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#:~:text=Gandhi%20(1940).%20Chapter%20%22More%20Hardships%22.%20Archived%202%20July%202012%20at%20the%20Wayback%20Machine

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#Fischer2002

[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#Fischer2002

[25] Gandhi (1940). Chapter “What it is to be a coolie”. Archived 11 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

[26] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#Herman2008

[27] S. Dhiman (2016). Gandhi and Leadership: New Horizons in Exemplary Leadership. Springer. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-1-137-49235-7.

[28] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#:~:text=Allen%2C%20Jeremiah%20(2011).%20Sleeping%20with%20Strangers%3A%20A%20Vagabond%27s%20Journey%20Tramping%20the%20Globe.%20Other%20Places%20Publishing.%20p.%C2%A0273.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D1%2D935850%2D01%2D4.

[29] https://blogs.elon.edu/sasa/2008/11/18/gandhi-and-the-phoenix-settlement/?msclkid=20f93651ace711ec8e6d674a0ee47c74#:~:text=Orginially%2C%20he%20only,and%20Nelson%20Mandella.

[30] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#Herman2008

[31] Power, Paul F. (1969). “Gandhi in South Africa”. The Journal of Modern African Studies. 7 (3): 441–55. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00018590.

[32] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#:~:text=Tendulkar%2C%20D.%20G.%20(1951).%20Mahatma%3B%20life%20of%20Mohandas%20Karamchand%20Gandhi.%20Delhi%3A%20Ministry%20of%20Information%20and%20Broadcasting%2C%20Government%20of%20India.

[33] https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Collected_Works_of_Mahatma_Gandhi/Volume_II/March_1897_Memorial

[34] Tendulkar, D. G. (1951). Mahatma; life of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Delhi: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India.

[35] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#:~:text=Herman%20(2008)%2C%20page%20125

[36] “South African Medals that Mahatma Returned Put on View at Gandhi Mandap Exhibition” (PDF). Press Information Bureau of India – Archive. 5 March 1949.

[37] https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/gandhi-and-burning-passes#:~:text=In%20August%201906,certificates%20were%20burnt.

[38] Rai, Ajay Shanker (2000). Gandhian Satyagraha: An Analytical And Critical Approach. Concept Publishing Company. p. 35. ISBN 978-81-7022-799-1.

[39] Parel, Anthony J. (2002), “Gandhi and Tolstoy”, in M. P. Mathai; M. S. John; Siby K. Joseph (eds.), Meditations on Gandhi : a Ravindra Varma festschrift, New Delhi: Concept, pp. 96–112, ISBN 978-81-7022-961-2, retrieved 8 September 2012

[40] Tolstoy, Leo (14 December 1908). “A Letter to A Hindu: The Subjection of India-Its Cause and Cure”. The Literature Network. The Literature Network. Retrieved 12 February 2012. The Hindu Kural

[41] Parel, Anthony J. (2002), “Gandhi and Tolstoy”, in M. P. Mathai; M. S. John; Siby K. Joseph (eds.), Meditations on Gandhi : a Ravindra Varma festschrift, New Delhi: Concept, pp. 96–112, ISBN 978-81-7022-961-2, retrieved 8 September 2012

[42] Charles R. DiSalvo (2013). M.K. Gandhi, Attorney at Law: The Man before the Mahatma. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-520-95662-9.

[43] Jones, Constance; Ryan, James (2009). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. pp. 158–59. ISBN 978-1-4381-0873-5. Archived from the original on 21 October 2015.

[44] Ashwin Desai; Goolem Vahed (2015). The South African Gandhi: Stretcher-Bearer of Empire. Stanford University Press. pp. 22–26, 33–38. ISBN 978-0-8047-9717-7.

[45] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#:~:text=Ashwin%20Desai%3B%20Goolem%20Vahed%20(2015).%20The%20South%20African%20Gandhi%3A%20Stretcher%2DBearer%20of%20Empire.%20Stanford%20University%20Press.%20pp.%C2%A022%E2%80%9326%2C%2033%E2%80%9338.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D0%2D8047%2D9717%2D7.

[46] https://theprint.in/opinion/ramachandra-guha-is-wrong-a-middle-aged-gandhi-was-racist-and-no-mahatma/168222/

[47] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#Herman2008

[48] Ashwin Desai; Goolem Vahed (2015). The South African Gandhi: Stretcher-Bearer of Empire. Stanford University Press. pp. 22–26, 33–38. ISBN 978-0-8047-9717-7.

[49] Edward Ramsamy; Michael Mbanaso; Chima Korieh. Minorities and the State in Africa. Cambria Press. pp. 71–73. ISBN 978-1-62196-874-0.

[50] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#:~:text=Herman%20(2008)%2C%20pp.%20136%E2%80%9337.

[51] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#Herman2008

[52] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#Herman2008

[53] Herman (2008), pp. 136–37.

[54] Herman (2008), pp. 154–57, 280–81

[55] https://blogs.elon.edu/sasa/2008/11/18/gandhi-and-the-phoenix-settlement/?msclkid=20f93651ace711ec8e6d674a0ee47c74#:~:text=The%20specfic%20birth,oppression%20and%20injustice.

[56] https://blogs.elon.edu/sasa/2008/11/18/gandhi-and-the-phoenix-settlement/?msclkid=20f93651ace711ec8e6d674a0ee47c74#:~:text=Because%20of%20the,and%20future%20scholars.

[57] For Kallenbach and the naming of Tolstoy Farm, see Vashi, Ashish (31 March 2011) “For Gandhi, Kallenbach was a Friend and Guide”, The Times of India.

[58] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#:~:text=Corder%2C%20Catherine%3B%20Plaut%2C%20Martin%20(2014).%20%22Gandhi%27s%20Decisive%20South%20African%201913%20Campaign%3A%20A%20Personal%20Perspective%20from%20the%20Letters%20of%20Betty%20Molteno%22.%20South%20African%20Historical%20Journal.%2066%20(1)%3A%2022%E2%80%9354.%20doi%3A10.1080/02582473.2013.862565.%20S2CID%C2%A0162635102.

[59] Smith, Colleen (1 October 2006). “Mbeki: Mahatma Gandhi Satyagraha 100th Anniversary (01/10/2006)”. Speeches. Polityorg.za. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013.

[60] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#:~:text=B.%20R.%20Nanda%20(2019)%2C%20%22Mahatma%20Gandhi%22%2C%20Encyclop%C3%A6dia%20Britannica%20Quote%3A%20%22Mahatma%20Gandhi%2C%20byname%20of%20Mohandas%20Karamchand%20Gandhi%2C%20(born%20October%202%2C%201869%2C%20Porbandar%2C%20India%20%E2%80%93%20died%20January%2030%2C%201948%2C%20Delhi)%2C%20Indian%20lawyer%2C%20politician%2C%20…

[61] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#:~:text=B.%20R.%20Nanda%20(2019)%2C%20%22Mahatma%20Gandhi%22%2C%20Encyclop%C3%A6dia%20Britannica%20Quote%3A%20%22Mahatma%20Gandhi%2C%20byname%20of%20Mohandas%20Karamchand%20Gandhi%2C%20(born%20October%202%2C%201869%2C%20Porbandar%2C%20India%20%E2%80%93%20died%20January%2030%2C%201948%2C%20Delhi)%2C%20Indian%20lawyer%2C%20politician%2C%20…

[62] Parel, Anthony J (2016), Pax Gandhiana: The Political Philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi, Oxford University Press, pp. 202–, ISBN 978-0-19-049146-8 Quote: “Gandhi staked his reputation as an original political thinker on this specific issue. Hitherto, violence had been used in the name of political rights, such as in street riots, regicide, or armed revolutions. Gandhi believes there is a better way of securing political rights, that of nonviolence, and that this new way marks an advance in political ethics.”

[63] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahatma_Gandhi?msclkid=b2356ed6acac11ec8fc4aaf546718bbf#:~:text=Stein%2C%20Burton%20(2010)%2C%20A%20History%20of%20India%2C%20John%20Wiley%20%26%20Sons%2C%20pp.%C2%A0289%E2%80%93%2C%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D1%2D4443%2D2351%2D1%2C%20Gandhi%20was%20the%20leading%20genius%20of%20the%20later%2C%20and%20ultimately%20successful%2C%20campaign%20for%20India%27s%20independence.

[64] McGregor, Ronald Stuart (1993). The Oxford Hindi-English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 799. ISBN 978-0-19-864339-5. Retrieved 31 August 2013. Quote: (mahā- (S. “great, mighty, large, …, eminent”) + ātmā (S. “1. soul, spirit; the self, the individual; the mind, the heart; 2. the ultimate being.”): “high-souled, of noble nature; a noble or venerable man.”

[65] Gandhi, Rajmohan (2006). Gandhi: The Man, His People, and the Empire. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-520-25570-8. …Kasturba would accompany Gandhi on his departure from Cape Town for England in July 1914 en route to India. … In different South African towns (Pretoria, Cape Town, Bloemfontein, Johannesburg, and the Natal cities of Durban and Verulam), the struggle’s martyrs were honoured and the Gandhi’s bade farewell. Addresses in Durban and Verulam referred to Gandhi as a ‘Mahatma’, ‘great soul’. He was seen as a great soul because he had taken up the poor’s cause. The whites too said good things about Gandhi, who predicted a future for the Empire if it respected justice.

[66] https://www.bing.com/search?q=indentured+labourers+south+africa&cvid=f981f661d85e444f9a5db88966572a7e&aqs=edge.3.69i57j0l3.14777j0j1&pglt=43&FORM=ANNTA1&PC=U531#:~:text=Image%3A%20pinterest.com-,Between%20the%20years%201860%20and%201911%2C%20152%20184%20persons%20were%20introduced%20as%20indentured%20labour%20into%20South%20Africa%2C%20the%20last%20batch%20having%20arrived%20on%20the%20S.S.%20Umlazi%20on%2021%20July%201911.,-This%20database%20of

[67] https://southasia.ucla.edu/history-politics/gandhi/gandhi-nobel-peace-prize/?msclkid=eda43190acc211eca85519d69c2befeb#:~:text=and%20the%20Nobel%20Peace%20Prize%20is,not%20empowered%20to%20confer%20posthumous%20awards.%C2%A0

[68] https://www.documentarytube.com/articles/why-mahatma-gandhi-never-won-the-nobel-prize?msclkid=99df57c7acc411ec86d675b75443ed05#:~:text=But%20he%20has%20never%20won%20it.%20The%20omission%20has%20been%20publicly%20regretted%20by%20later%20members%20of%20the%20Nobel%20Committee.%20For%20example%2C%20when%20Dalai%20Lama%20was%20awarded%20the%20Peace%20Prize%20in%201989%2C%20the%20chairman%20of%20the%20committee%20said%20it%20was%20%E2%80%9Cin%20part%20a%20tribute%20to%20the%20memory%20of%20Mahatma%20Gandhi.

[69] https://www.documentarytube.com/articles/why-mahatma-gandhi-never-won-the-nobel-prize?msclkid=99df57c7acc411ec86d675b75443ed05#:~:text=Last%2C%20but%20not%20least%2C%20while%20the%20committee%20considered%20giving%20him%20a%20posthumous%20award%20after%20his%20passing%2C%20the%20explanation%20was%20that%20there%20%E2%80%9CGandhi%20did%20not%20belong%20to%20an%20organization%2C%20he%20left%20no%20property%20behind%2C%20and%20no%20will.%20So%2C%20who%20should%20receive%20the%20Prize%20money%E2%80%9D%3F

[70] https://www.google.com/search?q=What+was+Dadabhaii+Abdulla+case+all+about+in+1893&rlz=1C1PNBB_enZA933ZA933&oq=What+was+Dadabhaii+Abdulla+case+all+about+in+1893&aqs=chrome..69i57j33i10i160l4.34360j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#:~:text=Mahatma%20Gandhi%2C%20as%20he%20is%20known%20by%20his%20followers%20with%20reverence%2C%20preached%20the%20philosophy%20of%20non%2Dviolence%20which%20has%20become%20even%20more%20relevant%20today.%20His%20commitment%20to%20non%2Dviolence%20and%20satyagraha%20(peaceful%20resistance)%20gave%20hope%20to%20marginalized%20sections%20of%20India.

[71] https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/gandhis-message-relevant-in-india-of-today/1718271#:~:text=Rajmohan%20Gandhi%2C%20while%20remembering%20his%20grandfather%2C%20said%20his%20ideals%20and%20principles%20are%20much%2Dneeded%20in%20India%20nowadays%20where%20intolerance%20rules%20the%20roost.

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: Biography, Gandhi, India, South Africa

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 28 Mar 2022.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi: The Making of the Mahatma in South Africa, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.