Global Symbols of Peace (Part 1): The Emerald Buddha

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 10 Apr 2023

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

The Revengeful, Greedy and Lustful Humanoids need to be regularly reminded about Peace in these times of Global Belligerence.[i]

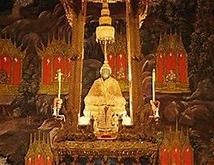

Demon Guardians in Wat Phra Kaew Grand Palace, ancient temple, complex, Bangkok, Thailand, where the Emerald Buddha is housed

This publication, in the series on the Global Symbols of Peace, discusses the different representative symbols signifying Peace. Amongst the myriad of symbols, in different cultures, religions, nations and legends, it is worthwhile highlighting the following:-

- Dove: A dove is a well-known symbol of peace, often depicted carrying an olive branch in its beak. This symbol originates from the biblical story of Noah’s Ark, where a dove was sent out to find dry land after the great flood. The White Dove, symbol of purity, often depicted in art and literature. The Dove of Peace, a sculpture by Pablo Picasso that has become a symbol of peace, worldwide.

- Olive Branch: The olive branch has been a symbol of peace for thousands of years. It is believed to have originated from ancient Greece, where it was used as a symbol of victory and peace.

- White Poppy: The white poppy is a symbol of peace and a non-violent alternative to the red poppy, which is often worn to commemorate war veterans. The white poppy was first introduced in 1933 by the Women’s Co-operative Guild in the United Kingdom.

- Peace Sign: The peace sign is a widely recognized symbol of peace, originally designed in 1958 by British artist Gerald Holtom. The symbol consists of a circle with three lines running through it, representing the letters “N” and “D” for “nuclear disarmament”.

- CND Symbol: The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) symbol is a stylised version of the semaphore letters “N” and “D” standing for “nuclear disarmament”. This symbol has become an internationally recognized symbol of peace.

- Cranes: In Japan, cranes are considered a symbol of peace and longevity. The tradition of folding paper cranes, or “origami,” is said to bring good luck, and is often associated with the hope for peace.

- World Peace Flag: The World Peace Flag is a simple design featuring a blue and white dove carrying an olive branch on a field of green. The flag was designed in 1921 by an international committee of women, and was intended to be a symbol of peace and unity among nations.

- Tibetan Prayer Flags: Tibetan prayer flags are colorful flags inscribed with prayers and mantras, often featuring the symbol of the windhorse. The flags are believed to bring peace, happiness, and good fortune to those who display them.

- Rainbow: The rainbow has been used as a symbol of peace in various cultures and traditions. Its vibrant colors are often seen as representing diversity and unity.

- Peace Bell: The Peace Bell a large bell in the United Nations headquarters in New York City. It is a symbolic bell that has been installed in many cities around the world, including Berlin, and Hiroshima. It is often rung to mark important events, such as the International Day of Peace, and to call for peace and unity.

- The Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands, which houses the International Court of Justice and the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

- The Peace Pagoda, a Buddhist stupa in Hiroshima, Japan, built as a symbol of peace and hope after the atomic bombing of the city in 1945.

- The Peace Memorial Museum in Hiroshima, Japan, which documents the atomic bombing of the city and advocates for peace and nuclear disarmament.

- The Peace Flame, a flame that burns continuously at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in Japan, representing the desire for global peace and nuclear disarmament.

- The Olive Tree, a symbol of peace and reconciliation in many cultures, particularly in the Middle East.

- The Ribbon of Peace, a sculpture in front of the United Nations headquarters in New York City that depicts a ribbon wrapped around a globe, symbolizing the unity and peace of all nations.

- The Mandela Peace Garden in Johannesburg, South Africa, dedicated to the legacy of Nelson Mandela and his efforts to promote peace and reconciliation.

While the Emerald Buddha represents the Buddhist faith and is associated with concepts such as compassion, wisdom, and spiritual enlightenment, it is not usually seen as a symbol of peace in the way that other symbols, such as the dove or the peace sign, are often used to represent peace on a global scale. However, the Emerald Buddha is a highly revered and significant symbol in Thai culture and Buddhism, although, it is not typically associated with global symbols of peace. The Emerald Buddha is a small statue made of green jadeite or jasper, and is believed to have originated in India or Sri Lanka. The statue is said to have been brought to Thailand in the 15th century, and has since been housed in the Temple of the Emerald Buddha in Bangkok.

The Emerald Buddha is known as “the palladium of Thai society”. This is a term that refers to the revered and highly esteemed statue of Phra Kaeo Morakot, also known as the Emerald Buddha. The statue is considered a national treasure and a symbol of Thai culture and identity. The Emerald Buddha is a small statue made of green jadeite or jasper, and is believed to have originated in India or Sri Lanka. It is highly revered in Thai culture and is seen as a symbol of prosperity, peace, and spiritual enlightenment. The statue is housed in the Temple of the Emerald Buddha in Bangkok, which is one of the most important Buddhist temples in Thailand.

The term “palladium” is often used to describe an object or symbol that is believed to be a safeguard or protector of a particular society or culture. In the case of Thailand, the Emerald Buddha is considered the palladium of Thai society, as it represents the country’s cultural heritage and serves as a unifying symbol for the Thai people. Located on the grounds of the Grand Palace and situated within Wat Phra Keo, The Emerald Buddha watches over the Thai nation. Yet the image’s history continues to reveal very little. Fable, myth, legend and fact intermingle, creating a morass for those who study the Emerald Buddha. While the Buddha is often mentioned in texts about Thailand, surprisingly little is written about it in great length. Beyond the image’s origins in documented history, the Emerald Buddha has traveled widely. It is important to examine the mythical origins of the Emerald Buddha as recorded in The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha and other sources and trace its history in Thailand beginning from its first appearance in the town of Chieng Rai. Upon its discovery in Chieng Rai, the Emerald Buddha became much coveted. The image moved throughout the region, from Chieng Rai to Lampang, Chieng Mai, Luang Prabang, Vientiane, Thonburi, and finally, to its present location in Bangkok. More than just a spoil of battle, the Emerald Buddha was believed to bring legitimacy and prosperity to all those who possess it. Thus kings throughout the region have desired to have the Emerald Buddha preside over and bring good favor to their capitals. The arrival of the Emerald Buddha in Bangkok marked the beginning and the rise of the Chakri dynasty. The first king of the Chakri dynasty Rama I validated his reign by moving the seat of his government to Bangkok and further strengthened his position through his possession of the Emerald Buddha. Rama I constructed a magnificent temple to house the Buddha, and today the image serves as a potent religious symbol for the majority of the Thai Buddhists in the region. A study of the iconography of this image may provide clues to its origins, and the stone used to create it in jasper, not emerald, may also suggest the original craftsmanship of the Emerald Buddha. The older a Buddha image is, the more power it is believed to have. The Emerald Buddha has a long history, possibly reaching back to India. Early in the Bangkok period, the Emerald Buddha was taken out of its temple and paraded in the streets to relieve the city and countryside of various calamities. The image also marks the changing of the seasons in Thailand, with the king presiding over the seasonal ceremonies. The power of the Emerald Buddha gives legitimacy to the king and protection to the nation. The image’s significance is built upon its long history and symbolism as an object of power for those able to possess it. During the Bangkok period not all who desired the Emerald Buddha were of royal lineage. The political significance of the Buddha also marked Thailand’s legitimacy during World War II. The image serve to mark political legitimacy outside the royal family. Today, King Rama IX, still wields considerable power and influence in Thailand. Some believe he is the second to the last king of the Chakri dynasty, with his successor marking the Tenth and final rule of the Chakri. Of the King’s children there are two candidates from whom he must choose, a prince and a princess. After Rama X who will be the caretaker of the Emerald Buddha? While the Emerald Buddha has had a murky past, its future is even less clear.

The Emerald Buddha is enshrined at the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, attired by the King of Thailand in Gold

Legend narrates that five centuries after the Buddha’s passing into Nirvana, there lived in India an ascetic named Nagasena. Nagasena was deeply devoted to the teachings of Buddha. His dedication directed him toward becoming a monk at Wat Asokarem in the city of Padalibutra. In Padalibutra, Nagasena’s devotion and love for the Buddha intensified. Confident in his abilities, Nagasena’s unwavering devotion and words sparked renewed interest for the people of the city who had forgotten Buddha’s teachings. Yet confidence and devotion aside, Nagasena’s heart grew heavy due to his daily mental and physical exertion. His sharing the Buddha’s teachings with the growing numbers of devotees in the city began to take its toll. Nagasena’s sadness soon reached the slopes of Mt. Meru and the powerful god Indra. Alarmed and concerned, Indra and Visnu descended from the mountain to lift the heavy burden from Nagasena’s heart. Waiting in the lush garden of Wat Asokaren, Indra and Visnu, surrounded by peacocks and the scent of jasmine, approached Nagasena as he entered the garden. Upon seeing the two deities, Nagasena dropped to his knees with his hands and face close to the ground. Indra asked Nagasena to stand up and share his troubles. Nagasena explained to the gods that Buddha’s teachings should be shared with all and that a image of the Buddha be created so that all could worship and pay reverence. The Buddha image had to be made to last forever, the likeness of the Buddha chiseled from precious stone. Compelled to help Nagasena, Indra instructed Visnu to go to the dreaded Mountain of Velu and seek out the most precious of all gem stones to be used for the image of Buddha. Staring at the ground, Visnu refused to budge, seeming to ignore Indra words. Indra’s patience quickly waned and he demanded that Visnu obey his request. Visnu dropped to his knees and told Indra of his fears of the dark demons filling the slopes of Mt. Velu. Speaking in a voice choked with fear, Visnu told Indra that those who try to remove the precious gems from the mountain would be turned to vapor by the demons. Indra calmed Visnu’s fears and offered to accompany him to Mt. Velu. In Marian Davies Toth’s version of this tale, she notes that “the demons and giants of the mountain guard its treasures as carefully as the kings of Siam guard their white elephants.”[1] The great leap in time between the creation of the first Buddha image and the kings of Siam noted in Toth’s version foreshadows the eventual resting place of the Emerald Buddha in Thailand. This time gap is not important, however; only the reference to Siam is relevant. In this case, the Hindu deities Indra and Visnu show their respect to the kings of Siam by acknowledging the difficult task of retrieving a stone great enough to produce the first image of Buddha. As the story continues, both Indra and Visnu confront the demons of Mt. Velu. Recognizing Indra, the demons drop their aggressive posture and bow to him, asking how they can be of service. Indra explains that a most precious stone is needed to create an image of Buddha that will inspire all who gaze upon it. Displeased with Indra’s request, the demons respond that they serve as guardians of the precious gems for King Isvara, a ruler living high up in the Himalaya Mountains. The demons note that the most precious of all these gems is a rare chunk of jade. Indra and Visnu are allowed to view the stone, and they marvel at the luminous green glow emanating from it. Convinced that this is the stone they must have, Indra asks if he might give the stone to Nagasena. In reverence of the Lord Buddha, the demons agree to Indra’s request. Indra and Visnu returned with the precious stone to the gardens of Wat Asokarem and presented it to Nagasena. At that point, Indra sensed that Nagasena heart was no longer burdened with grief. While Indra returned to Mt. Meru, Visnu stayed with Nagasena, taking on the form of a sculptor who created the likeness of the Buddha. Thus was the luminous chunk of jade transformed in the gleaming image of the Emerald Buddha. The Emerald Buddha was placed in a beautiful new temple with a roof of gold and attracted thousands of people from every corner of the land. This popular fable serves as the birth story of the Emerald Buddha. An image retrieved and sculpted by gods in honor of Buddha. An image well suited to serve as the palladium of Thai society.

The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha is a text tracing the mythical origins and travels of the Emerald Buddha. As yet there has been little attempt to determine what is factual and what is mythical in this account. The chronicle is generally considered to be a morass of information: it includes instances in which the Emerald Buddha is in two places at once, significant time discrepancies, and descriptions such as the king who could fly through the air to reach his desired destination in a short period of time. It would be easy to disregard the contents of this chronicle as mere fable, ignoring the possible merits hidden within it. At this time it is safe to say that there has been little academic research regarding The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha. The Nagara Krtagama, the fourteenth-century Javanese poem by Mpu Prapanca, was once regarded by academics such as C.C. Berg as offering little more than an author’s flight of fancy. While Berg’s criticisms do have merit, since questioning historical authenticity is important, his dismissal of this text should serve as caution to not simply to discredit a traditional history out of hand. Today, the Negara Krtagama is considered an important source of information for scholars seeking to unravel the histories of the Singasari and Majapahit periods in eastern Java. Unraveling The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha may likely prove a much more difficult task due to its many ambiguities. The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha was first translated into French, then into English, in 1932 by Camille Notton. Notton translated the Chieng Mai dialect (yuon) text, which was originally taken from a palm leaf manuscript found in Chieng Mai. This original manuscript is in the Pali language. According to Notton, there is no indication of the original author or a date of composition for The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha. There are also manuscripts about the Emerald Buddha found in neighboring countries. Laos, Cambodia, and the Shan States of Burma all acknowledge their own manuscripts of The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha. The fact that there is more than one manuscript seems to imply that there had been an older text that existed at an earlier time. Notton notes that S.S. Reinach, a member of the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres in Paris supports the idea that the later versions of the Emerald Buddha manuscript reflect some semblance of the original version of the chronicle. Notton further acknowledges Reinach’s judgments that there is evidence that the original manuscript must have been an object of particular esteem. The Chieng Mai manuscript came to the attention of a young Frenchman whose interest in Siam took him beyond his daily duties as a servant to the government of France. Camille Notton had a rather undistinguished career as a diplomat. Trained in Thai language at the Ecole des Langues Vivantes in Paris, Notton was appointed in August of 1906 as a student interpreter for the Bangkok legation. [2] He was transferred in 1916 to Chieng Mai and moved back and forth between Chieng Mai and Bangkok for several years. In 1930 he became a First-Class interpreter and was sent back to Chieng Mai from Bangkok in 1932. In 1935 Notton was promoted to Second-Class Consul and remained in Chieng Mai until 1938. According to Kennon Breazeale, there was no central-Thai version of the Chieng Mai annals in Camille Notton’s time, Notton must have thus gained a reading knowledge of the northern-Thai script in order to translate the annals. Notton’s translation of The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha marks the first translation of the text by a Westerner.

The chronicle’s first Epoch relates how, from his home in India, Nagasena first conceived the idea of creating an image of the Buddha to encourage the flourishing of Buddhism. Nagasena was aided by both Indra and Visnu, and proclaimed that the newly-produced image would last five thousand years. Nagasena also predicted the Emerald Buddha’s future importance in lands located beyond India. Nagasena had through his supernatural knowledge a prescience of future events, and he made this prediction: ‘The image of the Buddha is assuredly going to give to religion the most brilliant importance in five lands, that is in Lankadvipa (Sri Lanka), Ramalakka, Dvaravati, Chieng Mai and Lan Chang (Laos).’ Moreover, the five images of the Buddha, namely Phra Ken Chan Deng (Buddha-heart-sandal-red), which was made by King Pasena, Phra Bang (Buddha-partly; so called because as it is said in the chronicle of The Phra Bang, everybody among human beings and angels contributed a small quantity of gold, silver and copper for casting the statue), Phra Keo Amarakata (Buddha-crystal-smaragd), Phra Che Kham (Buddha-pure-gold) will ensure very great prosperity and give preeminence to the countries where they are established; and the kings of these places will excel all other kings. So shall it be.[3] The section of Notton’s translation in bold clearly notes the future significance that each image, including the Emerald Buddha, will have in the countries in which each image is established. Beyond being a self-fulfilling prophecy, the significance of the Emerald Buddha will be highlighted.

The second epoch of the Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha, moves to former Ceylon, notes a civil war in Pataliputra. Concerned about the safety of the Emerald Buddha, the ruler of Pataliputra sent the image to the King of Lankadvipa for safe keeping, intending to restore it to his kingdom once the fighting has ceased. The account continues by noting that the ruler of Pataliputra likely never journeyed to retrieve the image from Lankadvipa. Therefore, the image is said to have remained in Lankadvipa for two centuries. With the Emerald Buddha in Lankadvipa, Buddhism flourished. Lanka emerged as a stronghold of Buddhism and upon his death the Buddha himself sought celestial protection for Sri Lanka and its faith. According to Karen Schur Narula, “the belief in the Buddha’s statement upon his death would form the basis of Sri Lanka’s concept of itself as a place of special sanctity for the Buddhist religion.[4] The style of Buddha images appearing in Sri Lanka reflect a characteristically Sri Lankan craftsmanship, according to Dorothy Fickle. The most common pose of Sri Lanka’s seated images of the Buddha is that of virasana (yogic) position, the position that the Emerald Buddha of Wat Phra Keo shares. Yet based on these features alone, it is not possible to determine whether the Emerald Buddha originated in Sri Lanka. Burma The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha continues, noting that monks from Burma, dissatisfied with Buddhist scripture from India, ventured to Lanka to make transcriptions of texts there. The monks believed that the scriptures found at Lanka were the purest scriptures of the Buddha. Finishing their tasks in Lanka the monks made arrangements for their return to Pagan. Two boats set off for the return voyage, one carrying scriptures written by Sri Lankans, and the other carrying teachings for the people of Pagan as well as the image of the Emerald Buddha. As fate would have it, the boat carrying the Emerald Buddha never arrived in Pagan. Narula notes: Recorded history pays homage to King Anawratha as the legendary and historical ruler who united peoples and places under the banner of a Theravada Buddhist Burma. The fact that this king ruled some six hundred years after the date attributed to him in The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha should be laid aside. The earliest recorded religious contacts between Burma and Sri Lanka date to the eleventh century. Indeed, the priest known in the chronicle as Silakhanda may well be the Mon monk Shin Arakan whom according to tradition, worked under King Anawratha to convert the Burmese to Theravada Buddhism.[5] The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha records that Anuruddha flew back to Pagan, weary with the length of time it was taking for the boat carrying the scriptures (Tripitaka ) and the Emerald Buddha to arrive in his kingdom. It is worth noting that the term ‘flying’ often symbolizes divinity, therefore its mention within the chronicle may be much more than literal. Upon his arrival, Anuruddha received word that the long missing boat had arrived in Indrapatha Nagara (Angkor). Such a journey is possible but the likelihood of the boat being blown off course and arriving at Angkor would entail more skill than fate. If one did not want to travel over land and abandon his ocean-going vessel, one would have to navigate the Straits of Melaka and then head north to reach the coast of Cambodia avoiding possible mistaken landfalls all along the journey. While not mentioned in The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha, the Emerald Buddha could have traveled over the Isthmus of Kra, close to the site of Ligor. In this case it would be a short journey to the Gulf of Thailand with a continuation on to Cambodia. The film Emerald Buddha, Seat of the Center of the Earth[6], comments in passing about the myth of the Emerald Buddha being left at Ligor (Nakhon Si Thammarat) for 1,700 years. The film suggests that the Emerald Buddha was brought to Ligor by a ship carrying a princess. The film does not mention where the ship came from or who the princess was; it also fails to offer a time frame for this tale. Today, there is a wat located in Nakhon Si Thammarat that is said to contain a relic of the Buddha. One of the most revered temples in southern Thailand, Wat Phra Mahathat is a prominent landmark, its original pagoda said to have been built some 1700 years ago to house the relic brought from Sri Lanka. Yet whether or not the Emerald Buddha followed the same path as the relic at Nakhon Si Thammarat is unknown and speculative. Cambodia. The newly-arrived treasures came into the hands of Indrapatha, but this ruler of Angkor ignored Anuruddha’s demand to return both the Tripitaka and the Emerald Buddha to Burma. Angered by the news that the king of Angkor refused to return the treasured items, Anuruddha flew through the air to Angkor to scare Indrapatha and his associates. Anuruddha flew around Indrapatha and his men, slashing their necks with his sword. While bleeding, the men were not seriously wounded and Indrapatha, fearing Anuruddha’s powers, relinquished control of the Tripitaka. Yet the Pagan King Anuruddha, perhaps in his haste to leave Angkor, took only the boat containing the Tripitaka, leaving behind the statue of the Emerald Buddha. According to The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha, some time after Anuruddha, during the reign of Senaraja, an incident of grave consequences took place at Angkor that would once again relocate the Emerald Buddha. This incident involved the young son of an officer and Senaraja’s own son. The two boys commonly played together and each possessed a pet insect. The officer’s son had a pet spider while the Senaraja’s son kept a pet fly. The boys often let their insects play with each other until one day the spider killed and ate the fly belonging to Senaraja’s son. The king exploded with anger upon receiving this news and immediately had the officer’s son put to death by drowning. Upon the death of the officer’s son, a great naga appeared, creating a tremendous storm and flood that killed the king and most of the inhabitants at Angkor. A monk concerned for the safety of the Emerald Buddha took the image and traveled north. Narula attempts to link the ruler who perished in the tempest created by the naga to the Khmer King Dharmasoka whose death during the siege of Angkor in 1431 was followed by the defection of two important monks to the Siamese. Narula notes that “the past and the Chronicle overlap here; Angkor was abandoned.”[7] The Luang Prabang Chronicle and The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha Before continuing with the mythical history of the Emerald Buddha, it is important to consider the Luang Prabang chronicle. The Fine Arts Department in Bangkok argues that the 1967 publication of Tamnan Phra Keao Morakot (A Historical Account of the Emerald Buddha) contains the 1788 Thai translation of the Luang Prabang version of the history. Kennon Breazeale notes that since this version was rewritten in the Fifth Reign, it should be treated cautiously, since the author not only brought the history up to date but also may have ‘corrected’ some passages in the period prior to 1788.[8] Breazeale also feels that the date of the composition can be determined tentatively from the terms Lao Phung Dam (“Black-belly Lao”) and Lao Phung Khao (“White-belly Lao”). According to Breazeale, these were old terms known to the Thai, but they seem to be used here to indicate the northern region (Lanna and Nan) and the upper-Mekong region (Luang Prabang), which, during 1890-1899 were officially designated as the Lao Phung Dam and Lao Phung Khao circles, respectively. Breazeale believes that these terms would not have been used in such a composition after 1899, because of Thai policy of suppressing ethnic identifications in official toponyms. Given the Thai government’s efforts for the years prior to 1893 to find documents in provincial towns to support Thai territorial claims in the Mekong basin, Breazeale guesses that the anonymous document was written before 1893, hence his tentative dating of 1890-1892. The Luang Prabang chronicle parallels The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha for the most part with only a few details distinguishing them apart. For example, in the Luang Prabang’s version, Anuruddha sails on a Chinese junk rather than flying to Angkor. The Luang Prabang version also notes that Anuruddha tried to steal back the Emerald Buddha from Angkor disguised as a merchant but failed in his attempt. Both chronicles have the Emerald Buddha taken to the north after the devastating tempest at Angkor. Once it came in the north, the reigning king of Ayutthaya (Ayuddhya) Boran (King Atitaraj, according to the Luang Prabang text) took possession of the Emerald Buddha as well as its attendants. The image was kept at Ayutthaya Boran for many generations. The use of the term boran after the Ayutthaya period translates to ‘ancient’ in Thai, but the use of the term in the Luang Prabang chronicle is not clear. A relation to the king of Ayutthaya Boran, The king of Kamphaeng Phet, asked for the image and carried it off to Kamphaeng Phet where it stayed for a time. This Kamphaeng Phet king then allowed one of his son’s, who was governor of Lopburi, to keep the Emerald Buddha for one year and nine months, a time period agreed upon by both The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha and the Luang Prabang text. Both chronicles relate that a king of Chieng Rai (King Phromma That, according to the Luang Prabang text), friend of the king at Kamphaeng Phet, was allowed to take the image to Chieng Rai. The Chronicle of the Emerald Buddha notes that the image stayed in Chieng Rai until 1506. According to Narula, the Chieng Mai version of the chronicle explains that it was during the reign of Sen Muang Ma in the years 1388-1411 that the Emerald Buddha was hidden behind stucco in a Chieng Rai temple. Chieng Rai, Lampang, Chieng Mai, Luang Prabang, and Vientiane Perhaps the most reproduced aspect of the history of the Emerald Buddha is its remarkable discovery in 1434. The majority of books dealing with Thailand’s history mention this discovery of the Emerald Buddha in Chieng Rai. Depending on which sources are used, the Emerald Buddha is said to appear in either 1434 or in 1436. Those who quote W.A.R. Wood’s A History of Siam note the date 1436, while those who cite the chronicles use 1434. Yet what is important is not the slight discrepancy in the date of discovery, but the emergence of the Emerald Buddha from a mythical past to a historical reality. According to the history found in the chronicles, in 1434 the Phra Keo Morakot was inside a large stupa at Chieng Rai. When the stupa tumbled down after being struck by lightning, a monk noticed a Buddha image covered in gold leaf beneath the crumbled stucco. Believing that the image was composed of ordinary stone, the monks of the temple placed it in the wihan (temple sanctuary) along with the many other Buddhist statues. Chadin Flood writes: Two or three months later, the plaster that covered the statue that was lacquered over and then covered with gold leaves, chipped off at the tip of the statue’s nose. The head monk of the temple saw that indeed the statue inside was made of a beautiful green crystal. He therefore chipped out the rest of the plaster, and it was then seen by all that the statue was made of one solid piece of crystal without marks or imperfection.[9] The population of Chieng Rai and the surrounding regions soon flocked to venerate the Emerald Buddha. News was also sent to the ruler of Chieng Mai who ordered an elephant procession to transport the image (called Phra Mahamaniattanapatimakon according to the chronicles) to Chieng Mai. As the procession approached the crossroads leading to Lampang, the elephant carrying the Emerald Buddha became agitated and ran off down the road toward Lampang. The elephant’s mahout calmed his pachyderm then struggled to return it to the intersection, to continue the journey to Chieng Mai. Yet once again the elephant became excited and ran off toward Lampang. At this point it was decided that a more docile elephant would be chosen to carry the image, yet the next elephant also reacted in the same way, charging down the road to Lampang. The news of the combative elephants soon reached the ruler of Chieng Mai. Being a strong believer in the supernatural, he feared the consequences of the incident and felt that the spirit guarding the Emerald Buddha did not want the image to come to Chieng Mai. The ruler of Chieng Mai thus allowed the image to go to Lampang and stay at a temple built from alms given by the people of Lampang. The image remained in Lampang for the next thirty-two years, residing within a temple that even today is referred to as the Phra Keo.[10] According dynastic chronicles of the Bangkok Era (First Reign), in the year of the Chula Era, A. D. 1468, a new ruler of Chieng Mai came to power. He believed that the previous ruler should not have allowed the Emerald Buddha to stay in Lampang. Diskul Subhadradis confirms that “the Emerald Buddha was moved to Lampang from Chieng Mai in 1468.”[11] The Buddha was brought in procession to Chieng Mai and set up in a wihan. The Chieng Mai ruler ordered a prasat (spiral roof) for the temple housing the Emerald Buddha, but after repeated lightning strikes destroyed the roof, the idea was abandoned. Within the wat, the Emerald Buddha was kept in a cabinet and was put on public display only occasionally. The Emerald Buddha stayed in Chieng Mai for eighty-four years. Flood writes: In 1551 the ruler of Chieng Mai was Chao Chaiyasetthathirat, the son of the ruler (Phra Chao Phothisan) of Luang Prabang. The previous ruler of Chieng Mai gave his daughter, Nang Yotkham, in Marriage to Phra Chao Phothisan. She became his consort and bore him a son Chao Chaiyaset. When the latter was fifteen years of age, the ruler of Chieng Mai, his maternal grandfather, passed away. There was no other descendant to succeed him. High-ranking officials and Buddhist monks therefore agreed unanimously to offer the throne to Chao Chaiyaset, the eldest son of Phra Chao Phothisan and the grandson of the late ruler of Chieng Mai. His name was lengthened to Chao Chaiyasetthathirat.[12] http://www.hawaii.edu/cseas/pubs/explore/eric.html (9 of 24)7/17/2008 10:01:51 AM The Origin and Significance of the Emerald Buddha After Chaiyasetthathirat assumed rule of Chieng Mai, his father Phothisan passed away in Luang Prabang. Concerned that if he attended his father’s funeral, he might be prevented from returning to Chieng Mai, Chaiyasetthathirat decided to take the Emerald Buddha with him to Luang Prabang. He also claimed that taking it to Luang would allow his relatives the opportunity to venerate the image and make merit. The Chieng Mai chronicles record that Chaiyasetthathirat also decided to stay and rule Luang Prabang. The dynastic chronicles of the Bangkok era (First Reign) tell a slightly different story; while there is no mention of Chaiyasetthathirat’s rule of Luang Prabang, it is written that he was on good terms with his half-brother and thus decided to stay in Luang Prabang for three years, discussing the division of their inheritance. It is also indicated that the officials of Chieng Mai felt that Chaiyasetthathirat had stayed away too long. Breazeale writes that these officials of Lanna (Chieng Mai) were no longer willing to wait for Chaiyasetthathirat, and sought found another descendant of Mangrai dynasty to take the throne. This Shan prince, known as Mae ku, was a distant relative of Chaiyasetthathirat. The Chieng Mai chronicles again differ in their version of the story, recording that the officials chose a Buddhist monk called Mekuti, a relative of the late ruler of Chieng Mai. Yet neither text mentions any attempt by Chieng Mai to retrieve the Emerald Buddha from Luang Prabang. In any case, Mekuti or Mae Ku may not have had an opportunity to do anything. Chaiyasetthathirat came under serious threat of attack after the Burmese took Chieng Saen, north-east of Chieng Mai, and Bayin-naung’s forces gained the position to make an armed attack down the Mekong river. Thus, after twelve years in Luang Prabang, Chaiyasetthathirat decided to move his residence to Vientiane in the 1560’s, taking the Emerald Buddha with him. The image stayed in Vientiane for two hundred and fifteen years until 1778. Taksin and Chao Phya Chakri Around the time the Burmese captured and pillaged Ayuddhya in 1767, a young Siamese general fled the capital with a few hundred followers. Scholars have speculated about the origins of this Ayuddhya citizen, Taksin, who seems to have been born with the Chinese family name Sin, which when was then extended to ‘Taksin’ when he served as governor of Tak.[13] As he traveled south of the sacked city of Ayuddhya, Taksin was able to increase his following and go on the offensive, routing the Burmese. Remarkably, within a short period of time Taksin had reconstituted the kingdom and was crowned king in 1768. Indeed, during his fifteen-year reign of Siam, Taksin was able to both unite the kingdom and expand its territorial claims. With Ayuddhya so thoroughly destroyed, Taksin set up his new capital of Thonburi on the western side of the Menam Chao Phya, south of Ayuddhya. While Taksin set about the task of expanding his territory, one of his most accomplished generals also made a name for himself on the battlefield. A long-time associate of Taksin’s, Chao Phya Chakri was victorious in the majority of his battle campaigns; one of his few defeats took place at Phitsanulok in 1776. Due to famine and a lack of supplies, Chao Phya Chakri was forced to abandon Phitsanulok to the Burmese. According to W.A.R. Wood, During this invasion Maha Sihasura expressed a desire to meet Chao Phya Chakri, whom he had found to be the toughest of his antagonists. A meeting was arranged, and the Burmese General, himself a very old man, was astonished to find that Chao Phya Chakri was only thirty-nine years of age. Maha Sihasura prophesied that Chao Phya Chakri was destined to wear the crown; a prophecy which came true approximately six years later.[14] It should be noted that ‘Chakri,’ which designates the present dynasty, is a title rather than a family name. The title Chao Phya Chakri is found at various times in the history of Thailand. It is conferred upon a high-ranking military officer, who, upon accepting the title, will drop the name given to him at birth. The Chao Phya Chakri who served King Taksin was one of King Taksin’s top military commanders. In 1778, he subdued Vientiane and removed the Emerald Buddha from Vientiane, taking it to Thonburi. When Taksin acquired the Emerald Buddha, he placed it in a building near the site of Wat Arun, an action that has, curiously, been overlooked by many historians. The Emerald Buddha remained in Thonburi until Taksin’s death. Alleged to have become insane, Taksin was removed as king and put to death by Chao Phra Chakri, who in turn ascended the throne. When Chao Phra Chakri assumed the title Rama I, he moved the site of the capital across the Menam Chao Phra to its present location in Bangkok. The Emerald Buddha also traveled across the river, very likely accompanied with pomp and circumstance. To house the image, Rama I constructed Wat Phra Keo. After Rama I’s ascent to the throne in 1782, he proclaimed a celebration to mark the site of the new capital. The dynastic chronicles note that the three-day celebration and festival also honored the Phra Sirattanasatsadaram Temple that housed the Emerald Buddha. Flood comments: At the conclusion of the celebration, Rama I renamed the capital city to accommodate the name of the Buddhist statue of Phra Phuttharattanpatimakon; Krungthepmahanakhon Bawonrattanakosin Mahintharayutthaya Mahadilokphop Noppharattanaratchathaniburirom Udomratchaniwetmahasathan Amonphiman-awatansathit Sakkathattiyawisanukamprasit. This was to be the capital city that housed the Buddhist statue Phra Mahamanirattanapatimakon, made of the finest, most beautiful crystal. The statue indeed enhanced the honor of the king, who himself established this capital city of Krungthepmahanakhon.[15] Wat Phra Keo (Phra Sri Rattana Satsadaram) The temple of the Emerald Buddha known in Thai as Wat Phra Keo is the most famous and perhaps the most beautiful wat in Thailand. The official name of Wat Phra Keo is Phra Sri Rattana Satsadaram, which translates into “the residence of the Holy Jewel Buddha.” Wat Phra http://www.hawaii.edu/cseas/pubs/explore/eric.html (11 of 24)7/17/2008 10:01:51 AM The Origin and Significance of the Emerald Buddha Keo was built in 1784 by King Rama I and was constructed at the same time as the Grand Palace, which shares the grounds with Wat Phra Keo. Since its foundation in 1784, Wat Phra Keo has never been allowed to fall into decay. The bot, or chapel, of the Emerald Buddha contains three small chambers on the west, twelve salas –four on the northern and southern sides and two on the eastern side and western sides. A tower, or belfry, is located on the south end of the structure, and there is also a small bot on the south-eastern corner next to the bot that houses the Emerald Buddha. The bot of the Emerald Buddha was constructed according to the standard plan of the majority of Thai temples but with the specific purpose of housing the Emerald Buddha. The image of the Emerald Buddha sits upon an elaborate multi-terraced altar that is the focal point within the bot. The upper part of the altar, which was built during the original construction of the temple, rests upon a base added by King Rama III; on either side stand two images of the Buddha, said to personify the first two kings of the Chakri dynasty.[16] The bot of the Emerald Buddha has not changed much since its construction, though its woodwork was replaced by King Rama III and King Chulalongkorn. The beautiful doors and windows of the bot, as well as the copper plates that cover the floor, were installed during the reign of King Mongkut. The wall paintings representing the universe according to Buddhist cosmology and the various reliefs depicting the various stages of the Buddha’s life were partly restored under Rama III. The three chambers on the western side of the Bot were constructed by King Mongkut. The northern most chamber (Phra Kromanusorn) contains images of Buddha in remembrance of the kings of Ayuddhya, and the wall murals were painted by In Khong, a famous painter of the nineteenth century. Perhaps due to their highly visible location at Wat Phra Keo, the best known Thai paintings are of the Ramakien, the Thai version of the ancient Hindu epic Ramayana. Originating in India well over 2,000 years ago, the Ramayana is a literary epic dealing with a reincarnation on earth of Visnu, destined in his rebirth to rid the world of demons. The Ramakien was written during the reign of Rama I (1782-1809). The 178 mural panels depicting the Ramakien at the Temple of the Emerald Buddha were also created during Rama I’s reign and have received extensive restoration up to the present time. While elaborate and colorful, the Ramakien murals also serve a didactic purpose, exemplifying virtues such as honesty, faith, and devotion. The story relates how the king of Ayuddhya, beset by the intrigues of one of his wives, banishes his son Rama to the forest. Rama is the reincarnation of Visnu on earth, and his beautiful wife Sita is the reincarnation of the goddess Lakshmi. The beauty of Sita comes to the attention of the ruler of Langka (Sri Lanka), the great demon Ravana or Tosakan. He kidnaps Sita and Rama, along with his brother Laksmana, must call upon Hanuman the White Monkey to help free Sita. In their devotion to Rama, Hanuman and his monkey army agree to attack Langka. It is also Hanuman who ultimately discovers and destroys Ravana’s key to immortality by removing Ravana’s heart from a box and allowing Rama to kill the demon. http://www.hawaii.edu/cseas/pubs/explore/eric.html (12 of 24)7/17/2008 10:01:51 AM The Origin and Significance of the Emerald Buddha Hanuman’s loyalty is rewarded by Rama who builds a city in Hanuman’s honor. According to the Ramakien, the site of Hanuman’s new city was decided by the landing place of a magic arrow fired by Rama, and the boundaries of the town were determined by the circumference made by Hanuman’s tail. According to Rita Ringus, Hanuman was reward with the city of Lopburi.[17] Today, Lopburi is the site of a festival honoring the monkeys residing at an old Khmer temple. Each year, these monkeys receive a bountiful buffet of fruits and vegetables. After fourteen years of captivity in Langka, Sita was forced to prove her chastity through an ordeal by fire, in which she completed unharmed. Yet Rama remained unconvinced of his wife fidelity, and his suspicions were reinforced when he found a drawing of Ravana beneath Sita’s bed. Rama’s anger forced Sita to move to the forest where she gives birth to Rama’s son. In succeeding years, Rama and his son, unaware of their relationship to each other, battled for control of the kingdom. In time, a recognition and understanding occurred, and father, mother, and son were finally united to live happily in Ayuddhya. The story of the Ramakien is an elaborate and important part of the art-works displayed at Wat Phra Keo. While the origin of the Ramakien is Indian, the story has been assimilated by the Thai, and is known by the majority of the people of Thailand. Along with other works of art, the presence of the Ramakien murals reinforce the importance and meanings associated with the Emerald Buddha, which watches over all things associated with being Thai. Continuing with the description of the bot of the Emerald Buddha, Rama I also placed twelve salas around the bot. Each contains fascinating remains brought from various regions, such as Cambodia and Java. Indeed, it was within one of these salas that the famous inscription of Ramkamhaeng resided, until it was moved to the National Library in 1924.[18]A sala on the western side of the bot contains an important bronze image of a rusi, or hermit, said to have the power to healing the sick. The small chapel on the southwestern corner (Phra Gandhararaj) and the high belfry were both built during the reign of King Mongkut.[19]The buildings on the platform to the north of the Bot are occupied by a library and another small chapel in the northwest corner. The focus of this northern collection of structures is the Mahamandapa, a square pavilion erected by Rama I on the site of the ancient library, which was destroyed by fire upon its completion. This pavilion was built for the purpose of housing sacred scriptures and was restored by King Mongkut. The platform or terrace upon it which it stands was enlarged by King Mongkut. At the same time, Mongkut also constructed the stupa Phra Sri Ratanachetiya, the building of which was completed by King Chulalongkorn, who adorned it with gold-colored tiles.[20] Also begun in 1855, the pantheon was originally planned as a special chapel for the Emerald Buddha but was later found to be too small for ceremonial purposes. Notton comments that the pantheon was renewed in 1903 after it had been partly destroyed by fire. During the reign of Rama VI, the king placed statues of his five ancestors in the pantheon to be worshipped at certain times of the year.

http://www.hawaii.edu/cseas/pubs/explore/eric.html (13 of 24)7/17/2008 10:01:51 AM The Origin and Significance of the Emerald Buddha On the northern part of the terrace is a model of Angkor Wat that was begun by King Mongkut and completed by King Chulalongkorn. In the northeastern corner of the courtyard, the library, with its beautiful exterior and elaborate interior, was built by Rama I for storing sacred books. The magnificent bookcases of the library were made of lacquered wood inlaid with mother-ofpearl, at the request of Rama I. Besides all the structures that compliment Wat Phra Keo, there are also several guardian figures of more recent workmanship, bronze images of lions, elephants, oxen and monkeys. The nine towers standing in a row on the eastern side of the temple ground were erected by Rama I. The colors of the glazed tiles with which they are covered are different for each tower and correspond with the colors of the nine planets. Wat Phra Keo is clearly an appropriate showcase for the palladium of Thai society.

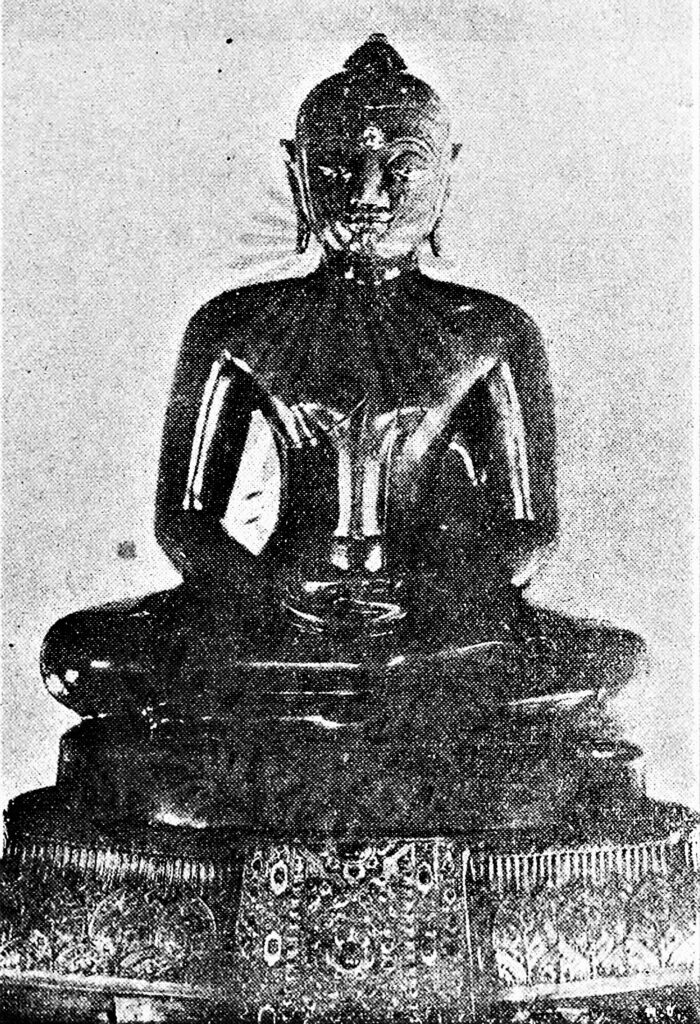

An original photograph of the Emerald Buddha without its golden, expensive, ceremonial and decorative attire, taken in 1932

Regarding a detailed description of the Emerald Buddha it sits in the virasana position, a Yogic common meditation position for seated Buddha images in most of Thailand. Dorothy Fickle notes that “especially in southern India, Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, including Thailand, the right leg merely lies on top of the left leg in the ‘hero pose’ or virasana.”[21] This contrasts with the ‘adamantine’ pose in which the legs are fully crossed, with each foot resting on the opposite thigh. The Emerald Buddha itself sits under a canopy on a high-tiered pedestal decorated with gold leaf. The Emerald Buddha is 66 centimeters high, and its lap measures 48.3 centimeters.[22] The image has a round based, top-knot which is smooth, terminating in a dulled point marking the top of the image. The face of the Emerald Buddha has a gold third eye inset above its pronounced eyebrows. The eyes of the image are cast downward giving the image a placid appearance. The nose and mouth are small, and the mouth is closed. The ears are elongated, indicating the figure’s divine status. The torso of the image sits in an upright posture with smooth, rounded shoulders, an unpronounced chest, and a slightly protruding belly. The torso also appears to wear ‘wet’ drapery, with the robe clinging smoothly to it. The elbows of the statue almost rest on the thighs. The hands rest on the lap with the up-ward facing right palm resting in the palm of the left hand. This is the Dhyanamudra position indicating the ‘Buddha of the West’. The Emerald Buddha was carved resting upon a platform, while this base itself rests on a gold lotus blossom. Craftsmanship and Other Aspects According to Hiram Woodward, the Emerald Buddha is an aerial image, associated with Indra’s heaven.[23] The image has sometimes been linked to the Phra Sihing Buddha, which is a ‘watery’ image of Sri Lanka origin. It is possible that the Emerald Buddha was crafted in Sri Lanka, however, most art historians point to other locations of origin, with no general agreement. http://www.hawaii.edu/cseas/pubs/explore/eric.html (14 of 24)7/17/2008 10:01:51 AM The Origin and Significance of the Emerald Buddha Speculation on the craftsmanship has stirred controversy in the past. King Mongkut issued a declaration that the Emerald Buddha was made of jade and concluded from this that the stone used for the image had been brought from China. Challenging King Mongkut’s interpretation has proved unpopular. For example, when one art historian contended that two famous Thai Buddha images, Phra Sihing Buddha and the Emerald Buddha, “were not as commonly thought, from India but were locally made,” he was strongly criticized for causing confusion and undermining the fame and authenticity of the images.[24] Surprisingly, Subhadradis does not provide an illustration of the Emerald Buddha and says nothing of its origins in his text on the subject. The renowned scholar of Thai art, Hiram Woodward, also makes no stylistic observations about the Emerald Buddha in his 1997 study. Lingat ascribes the image to the Chieng Saen School of the late fourteenth century and suggests that it may have been hewn out of a stone found in the Nan province, which has been analyzed as a variety of quartz.[25] Le May also feels that the Emerald Buddha is clearly of local manufacture and probably belongs, as Lingat suggests, to the Chieng Saen School.[26] Le May states that he is familiar with the greenish stone found in the Nan region, attributing his knowledge to the stone Buddha images available for purchase at local markets. Basing his argument on stylistic grounds, Jean Boisselier contends that the image was probably not carved in Lanna. He notes that according to one tradition it arrived from Sri Lanka, while another says it came from South India. Yet, says Boisselier, art historians are not in the position to draw any definite conclusions about such an origin.[27] He believes that the Emerald Buddha is probably made of jasper, which is not a gem stone and which usually appears in the colors red, yellow or brown. It is worth noting, however, that the color green does not seem to be a feature of jasper. Both Chieng Rai and Chieng Mai are along the trail that led from the Salween estuary into southwest Yunnan Province in China. Breazeale notes that the overland trade along this trail is very old and presumably pre-dates the founding of Chieng Rai. Despite some rapids, Chieng Mai was a relatively easy contact down-river with the gulf. Given these geographical links and the established fact that Chinese-style celadons were produced in the Sukhotai kingdom, Breazeale feels it is not inconceivable that the stone used to create the Emerald Buddha was brought to Lanna from a quarry in China or South Asia and that the sculptor likewise came from elsewhere. The Significance of the Emerald Buddha In Thailand, images of the Buddha, particularly stone or gem images, have long been associated with having special powers. Buddha images have also long served as objects of veneration and worship. They appear on small tables and altars in homes, schools, and temples; they are found in police courts where people are required to take oaths; various organizations make their pledges before them; and they appear in the committee rooms of provincial capitals where officials gather for services on national holidays. Kenneth Wells points out that “whenever a http://www.hawaii.edu/cseas/pubs/explore/eric.html (15 of 24)7/17/2008 10:01:51 AM The Origin and Significance of the Emerald Buddha chapter of monks performs a ceremony, as at a funeral of an important person or laying a cornerstone of a great building, an image of the Buddha is usually present and a sacred sincana cord is often attached and held by chanting monks.”[28] Images of the Buddha are brought out from their respective sites, to be carried in procession at times of drought. At Wat Si Ubon Rattanaram in Northern Thailand there is a priceless topaz Buddha image the size of a small table lamp which is used on occasion for a rain-making ceremony. Chieng Mai also houses two small images believed to possess rain-making powers. One of these Buddha images is made of quartz crystal and the other is made of grey stone said to be of Indian craftsmanship. Buddha images were also brought out in procession during times of plague or epidemics. The Emerald Buddha itself has served to ward off the effects of epidemics. In the cholera epidemic of 1820, for example, the Emerald Buddha was taken from Wat Phra Keo and carried throughout Bangkok in both land and canal processions. Lingat notes that the 1820 epidemic was the worst in the history of Siam: Corpses which there was no time to burn were heaped up in the monastery ‘like stacks of timber’ or else left to float about in the river and the canals. The people fled in a panic from the capital; the monks deserted the monasteries, and the whole machinery of government was at a standstill. The king even released the royal guard from their duties in the palace. There were great ceremonies of propitiation; the Emerald Buddha and the precious relics kept in the monasteries were taken out in procession through the streets, and on the canals of the city, attended by high dignitaries of the Church who scattered consecrated sand and water. The king and the members of the royal family maintained a rigorous fast. The slaughter of animals was completely forbidden, and the king caused all supplies of fish, bipeds, and quadrupeds, offered for sale, to be bought up in order that they might be liberated. All criminals, except the Burmese prisoners of war, were released from prison. The scourge abated at last after taking 30,000 victims within a few months. Rama IV brought an end to the custom of removing the Emerald Buddha during times of epidemic for fear that it could suffer damage Also, Rama IV hoped that people would realize that diseases are caused by germs, not by evil spirits or the displeasure of the Buddha. After that point in history, a sacred cord was attached to the image so that ceremonies could take place outside of the temple on its behalf, without moving the image. By contrast, the Phra Sihing Buddha image, which is today located in the Buddhaisawan Chapel near the National Museum in Bangkok, is still removed from its site for short periods of time. During the Songkran festival in April, the Phra Sihing Buddha is taken out onto the Promenade Ground in front of the museum, where worshippers can sprinkle it with a few drops of water as a merit-making gesture. Chao Phra Chakri is believed to have collected over twelve hundred Buddha images from around the country while serving under King Taksin. These images were brought to Bangkok and installed in temples that were built when Chao Phra Chakri ascended the throne. After being crowned Rama I, the new king installed a regnal image at the Royal Chapel, The Phra Chai http://www.hawaii.edu/cseas/pubs/explore/eric.html (16 of 24)7/17/2008 10:01:51 AM The Origin and Significance of the Emerald Buddha Buddha. Seated on an elaborate pedestal beneath a five-tiered umbrella, this ‘Lord of Victory’ image is depicted in ‘the touching the earth’ mudra and holds a fan before his face, which, as Dorothy Fickle points out, suggests the manner of a monk in Thai society.[29]The function of the Phra Chai image was to ensure victory in the field of battle for the ruler, thus it accompanied the king on all his military excursions. It is believed that the older the image is, the more potent its power. In a temple containing several Buddha images, one or two in particular may be venerated for their unusual powers. Consecrated images are also believed to possess nana, or knowledge, which leads to release or transformation, and some images are even believed to have certain likes and dislikes. For example, the Phra Bang Buddha image was believed to have caused a series of disasters while it remained in the same city as the Emerald Buddha, and for this reason, Rama I finally returned it to Vientiane in 1782. In similar fashion, when the Phra Jinasi Buddha was removed from Pitsanulok and brought to Bangkok, the city suffered a three-year drought and the government official in charge of the image took ill and died.[30] According to Sombot Phlainoi, the first six kings of the Chakri dynasty had their own regnal crystal Buddha images.[31] The practice of creating regnal images was discontinued when Rama VII died before his own consecration. It is still taboo to inquire after the king’s health, and in the past, it was even forbidden to allude directly to the death of a king. Thus the term used to express this event is satec svargagata, ‘to migrate to heaven.’[32] Ritual Significance of the Emerald Buddha While many ceremonies are performed throughout the year on the grounds of the Grand Palace, which encloses Wat Phra Keo, most of these only briefly acknowledge the presence of the Emerald Buddha. One such ceremony is Chakri Day, which allegedly began April 6, 1782. On this national holiday honoring the founding of the Chakri dynasty, the king takes a leading part in the ceremony. Rama IX, the present king of the Chakri dynasty is accompanied by the Queen, members of the royal family, the Premier, and officials in the Ministry of Defense and other government departments. According to Kenneth Wells, the king and queen first pay homage to the Emerald Buddha, the palladium of the Chakri dynasty, in Wat Phra Keo. They then visit the pantheon, also on the grounds of the Grand Palace. It is at the pantheon where both the king and queen pay their respects to the images of previous Chakri rulers that have been enshrined there. Opened to the public only during the annual Chakri day commemoration, the small building is thronged by visitors throughout this day.[33] Next, the Royal family stops at the statue of Rama I to pay their respects and lead a procession of dignitaries who leave wreaths at the site. The ceremony closes with the king lighting candles and paying homage to Buddha and his ancestors. Quaritch Wales also notes a brief appearance by the Emerald Buddha in the coronation http://www.hawaii.edu/cseas/pubs/explore/eric.html (17 of 24)7/17/2008 10:01:51 AM The Origin and Significance of the Emerald Buddha ceremony. As part of his description of the coronation of Rama VI (King Prajadhipok), Wales records the Acceptance of the Headship of the Buddhist Religion: During the coronation ceremony the king is carried in procession to the Chapel Royal (Wat Phra Keo). He wore a Great Crown while seated on the palanquin, but when on foot before mounting the palanquin, after leaving it, and while on his way to enter the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, he wore a Royal Hat. On entering the Chapel Royal the king made offerings of gold and silver flowers and lit candles before the Emerald Buddha and the images of Buddha representing the earlier kings of the dynasty. Then in full congregation of the higher clergy of the kingdom, he made a formal declaration of his religion and his willingness to become Defender of the Faith.[34] The coronation ceremony was last performed by King Rama IX upon his assent to the throne. It is one of many ceremonies in which the king pays homage to the Emerald Buddha; however, today the number of times a king takes part in ceremonies that require homage to the Emerald Buddha has been reduced. The Oath of Allegiance or the Drinking Water of Allegiance, in which the Emerald Buddha and other relics were honored, was once of great importance to the absolute monarchy. [35]But after the absolute monarchy was dissolved in 1932, this ceremony was no longer performed, having been replaced by Constitution Day. The Ceremony of the Expulsion of Disease was also ended by Rama IV after the cholera epidemic of 1820, thus eliminating its use in the future. Today the most significant ceremony associated with the Emerald Buddha takes place three times a year. The king climbs up behind the grand pedestal that supports the Emerald Buddha and cleans the image by wiping away any dust that has collected and changing the headdress of the image. One of the king’s royal attendants then ascends and changes the elaborate garments of the image while the king worships in silent prayer. As the designated Protector of the Faith, the king is the highest master of ceremonies for all Buddhist rites. Currently this distinction falls on Rama IX whose search for the meaning of life begins and ends within the power and influence of the charmed circle of the Emerald Buddha. The Emerald Buddha goes through this ceremony in March, the hot season, July. the rainy season, and November, the cool season. Rama I introduced the ceremonies marking the change of seasons as well as providing the garments in which the Emerald Buddha is dressed. However, he only introduced the ceremony for the hot season and the rainy season. Rama III (King Chulalongkorn) introduced the ceremony for the cool season during his reign. The hot season costume includes a pointed crown of gold and jewels, and a set of jeweled ornaments that are banded at various points on the body from the shoulders to the ankles. The rainy season costume is marked with a flaming top-knot headdress made of gold, enamel and sapphires. The gold robe is decorated with rubies and arranged with the robe draping over the left shoulder only, leaving the right shoulder bare. From the waist of the image down to the ankles, the image is covered with gold garments. The costume for the cool season introduced by Rama III is a mesh robe or covering made of gold beads. This elaborate garment covers the http://www.hawaii.edu/cseas/pubs/explore/eric.html (18 of 24)7/17/2008 10:01:51 AM The Origin and Significance of the Emerald Buddha entire body of the Emerald Buddha from the neck down and is draped like a poncho. Political Significance The Emerald Buddha’s mystical origins, its desirability by past rulers seeking to legitimize power, and the powers attributed to older Buddha images, have all allowed the Emerald Buddha to become a potent religio-political symbol and the palladium of Thai society. The Emerald Buddha also serves to legitimize the power of the Chakri dynasty as well as its present king. The current king of Thailand, King Bhumibol Adulyadej, has recently celebrated the fiftieth year of his reign. His legitimacy is reflected in his ability to defuse major crises in his country. In the recent past, the king has intervened to end crises between the military and students in October 1973, and most recently, in May 1992. Near the end of that May, the king ordered General Suchinda crawl on his knees in front of him, the media, and all the world, to shame Suchinda publicly. Broadcast over international television, this dramatic disgracing of an important military leader allowed the rest of the word to see the immense power the king of Thailand is still able to yield. Although the king does not have any political or administrative power under the system of constitutional monarchy, his role in times of political crises has been crucial. The Thai people view him as a sacred and spiritual leader who serves as a symbol of unity. Because of this, the monarch remains above all conflicting political groups. Support from the monarchy remains an indispensable source of political legitimacy. A political leader or regime, even a popularly elected government, cannot be truly legitimized without the king’s blessing. The king is the caretaker of the Emerald Buddha, and the possession of the image itself symbolizes the legitimacy of the king. In turn, the Emerald Buddha brings prosperity to the land in which it is kept. The legitimacy of power through the possession of the Emerald Buddha has not always been in the hands of the Chakri dynasty. When Prince Mahidol was out of the country there was no one to assume the role of King of Thailand, and in 1932, the monarchy lost its governing role in a coup d’état. A short time later, a youthful military leader gained the position as premier from Phraya Phahon. In 1938, Phibun Songkran was selected by the National Assembly to succeed Phahon. He held both the premiership and the post of Commander-in-Chief of the Army, and in 1941 assumed the role of Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. As a reward for winning the Indo-Chinese War against the French, Phibun was conferred the rank of field marshal in July 1941; he thus reached the summit of his military career at the relatively young age of fortyfour.[36] At the beginning of World War II, Phibun believed that Japan would emerge victorious at war’s end. Thus, on December 14, 1942, he signed a secret agreement with the Japanese, committing Thai troops to Burma.[37] Judith Stowe writes that on December 21, matters were taken a step further by the conclusion of a formal treaty of alliance between the two Buddhist countries: “To emphasize its solemn and binding nature, the treaty was signed by Phibun and Tsubokami in front of the Emerald Buddha, considered the most sacred object in the whole of Thailand.”[38] http://www.hawaii.edu/cseas/pubs/explore/eric.html (19 of 24)7/17/2008 10:01:51 AM The Origin and Significance of the Emerald Buddha By 1944, Phibun’s campaign to urge people in Bangkok to leave the area drew suspicions that Phibun was deliberately abandoning the capital founded by the Chakri dynasty to promote his own royal ambitions. Indeed, Phibun drew up bills to have the capital moved to Petchaboon and construct a new Buddhist city at Saraburi, the place of his birth. Yet government officials were reluctant to move to Petchaboon because of its lack of infrastructure. Electricity, potable water supplies, stores, and telephones were non-existent, and the road to the site was still unfinished. According to Stowe, “The valley up which Petchaboon was situated was so insalubrious and inhospitable that thousands of conscript workers were dying of malaria, inadequate health care, and lack of food.”[39] Yet Phibun remained undaunted by the mounting problems and loss of human life attributed to his project. He ordered the removal of all royal and national treasures to Petchaboon and the building of a grandiose new temple to house the Emerald Buddha. As Stowe notes, To set the seal on these developments, Phibun intended to visit Petchaboon on April 23,1944, with the Supreme Patriarch of the Buddhist Sangha for the ceremonial laying of the cornerstone of the new capital. But when the news of these plans was broadcast, it evoked comment from a Thai-language radio station based in India, which led Phibun to fear that the ceremony would be disrupted by an Allied bombing raid.[40] In July of 1944, Phibun’s bills for the construction of Saraburi were thrown out. Perhaps the Emerald Buddha had no plans of leaving Bangkok for the mosquito-infested land of Petchaboon. Yet Phibun managed to keep his colorful career going until 1957 with his once great ambitions kept to himself. On February 23, 1991, the National Peace-Keeping Council announced the total seizure of power by the armed forces. Martial law was declared by Generals Sunthorn and Suchinda. The two generals flew to Chieng Mai to meet with the king and to gain his blessing for their new government. Rama IX granted the generals royal amnesty and endorsed their new government. The king’s endorsement fended off any possible student protest and reassured foreign opinion. Elliott Kulick & Dick Wilson write that “over the next hours the final blessing came from the Supreme Patriarch of the Buddhist sangha, after which the two generals donned full dress uniform to go to the Grand Palace and the Temple of the Emerald Buddha.”[41] At Wat Phra Keo the two generals paid ceremonial respect to the Emerald Buddha, seeking final legitimacy for their fledgling government. In the presence of the Emerald Buddha each general swore to administer the Thai nation honestly and justly, for the well-being of the people of Thailand. The present government under Chuan Leekpai has also called upon the Emerald Buddha in the hope of raising the country out of its economic crisis and ensuring the stability of the new regime. Conclusion The palladium of Thai society continues to watch over the country. Perhaps in time the Emerald Buddha’s mythical past will share more of its secrets. Interest amongst western scholars in the history of the Emerald Buddha seems to have peaked in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s. Much of http://www.hawaii.edu/cseas/pubs/explore/eric.html (20 of 24)7/17/2008 10:01:51 AM The Origin and Significance of the Emerald Buddha what we do know about the Emerald Buddha comes from Western government officials who took an interest in the history and culture of Thailand during their respective tours of duty. The various annals or chronicles that speak of the creation and mystical travels of the Emerald Buddha have been found in the neighboring regions of present day Thailand. The presence of so many chronicles seems to indicate that there once was an original document from which the rest of the annals were created. It is possible that the Emerald Buddha, making its grand entrance in Chieng Rai, is a reproduction of a now lost version of the Emerald Buddha. For that matter, perhaps it is the great Buddha image that visited “five lands,” as predicted by Nagasena. The power of the Emerald Buddha seems to predate its discovery in Chieng Rai, making it a much coveted image among those who would count themselves as ‘men of prowess’ following its discovery. The Emerald Buddha was more than a mere spoil of battle. Along the its journey, the image gained fame for its power to bring prosperity to the kings and capitals in which it resided. Possession of the image gave and still gives legitimacy to those in power. The arrival of the Emerald Buddha to Bangkok marked the beginning of the rise of the Chakri dynasty. By taking the image across the Menam Chao Phra and building a temple to house it, Rama I validated himself as king and created the current capital of the country. Speculation continues about the origin of the stone used and the craftsmanship of the Emerald Buddha, but the creation of images such as the Emerald Buddha do not reveal the artists behind the image. It seems common practice for the creators of Buddha images not to inscribe their identities, choosing instead to remain anonymous. The stone used could be traced to many regions, with some art historians believing that the stone and it manufacture were of local origin in northern Thailand. Some scholars have dated the iconography of the Emerald Buddha to the Chieng Saen period. Placing the stone in an earlier era and noting the less than gem-like qualities of the stone has created controversy in the past. Art historians studying the image have occasionally received a strong rebuke from those in high places in Thailand. It is important to note that none of these scholars has ever had a close look at the image, their ideas should therefore be received with reservation. The magical powers linked with the Emerald Buddha have in the past been associated with the purging of evil spirits and disease. While no longer paraded in the streets, the image continues to be associated with the welfare of the country. Magical powers are also attributed to many Buddha images kept in Thailand. One of the more common powers associated with Buddha images is the ability to conjure up the rains in times of drought. In recent times the Chakri dynasty has not been alone in seeking legitimacy through the Emerald Buddha. After 1932, when the monarchy was reduced to constitutional status, the many premiers who have sought political office have also gone to the Chapel Royal to gain symbolic legitimacy from the Emerald Buddha. During World War II, Phibun Songkram came very close to moving the Emerald Buddha away from the present capital to a new capital at Saraburi, his birthplace. http://www.hawaii.edu/cseas/pubs/explore/eric.html (21 of 24) 7/17/2008 10:01:51 AM The Origin and Significance of the Emerald Buddha Last year Rama IX celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of his ascent to the throne. To mark the grand occasion, he was given a quartz crystal image of the Buddha. Rama IX’s long career of meritorious works and defusing volatile situations in his country has strengthened his status as well as increased the potency and power of the Emerald Buddha. The Emerald Buddha is the protector of the country, its significance resting upon its long history and Nagasena’s prediction that it would bring prosperity and preeminence to each country in which it resides.

The Emerald Buddha in the three seasonal decorations,

From left to right: Summer season, Rainy season, Winter season

The Emerald Buddha is adorned with three sets of gold seasonal decorations: two were made by Rama I, one for the summer and one for the rainy season, and a third made by Rama III for the winter or cool season.[10] In 1996 to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of King Bhumibol Adulyadej, the Bureau of the Royal Household commissioned a replica set of the seasonal decorations to be made in all the same materials. This new set was funded entirely by donations. The original set, which were made over 200 years ago, were retired and are on display at the Museum of the Emerald Buddha Temple in the Middle court of the Grand Palace.[14]

The decorations are changed by the King of Thailand, or a senior member of the royal family in his stead,[15] in a ceremony at the changing of the seasons – in the 1st Waning of lunar months 4, 8 and 12 (around March, August and November).[16]

For the three seasons, there are three sets of decorations for the Emerald Buddha:[3][16]

- Hot/summer seasonfrom March to August – a stepped, pointed crown (makuṭa); a breast pendant; a sash; a necklace, a number of armlets, bracelets and other items of royal attire. All items are made of enameled gold and embedded with precious and semi-precious stones.

- Rainy seasonfrom August to November – a pointed headpiece of enameled gold studded with sapphires; a gold-embossed monk’s robe draped over one shoulder (kasaya).

- Cool/winter seasonfrom November to March – a gold headpiece studded with diamonds; a jewel-fringed gold-mesh shawl draped over the rainy season attire.

The sets of gold clothing not in use at any given time are kept on display in the nearby Pavilion of Regalia, Royal Decorations, and Thai Coins on the grounds of the Grand Palace, where the public may view them.

Early in the Bangkok period, the Emerald Buddha was occasionally taken out and paraded through the streets to relieve the city and countryside of various calamities (such as plague and cholera). This practice was discontinued during King Rama IV‘s reign as it was feared that the image could be damaged during the procession and the king’s belief that; “Diseases are caused by germs, not by evil spirits or the displeasure of the Buddha”.

The Emerald Buddha also marks the changing of the seasons in Thailand, with the king presiding over seasonal ceremonies. In a ritual held at the temple three times a year, the decoration of the statue is changed at the start of each of the three seasons. The astrological dates for the ritual ceremonies, at the changing of the seasons, followed are in the first waning moon of the lunar calendar, months 4, 8 and 12 (around March, July, and November). Rama I initiated this ritual for the hot season and the rainy season; Rama III introduced the ritual for the winter season.[4][13] The decoration which adorn the image, represent those of monks and the king, depending on the season, an indication of its symbolic role “as Buddha and the King”, which role is also enjoined on the king who formally dresses the Emerald Buddha himself. The costume change ritual is performed by the king who is the most elevated master of ceremonies for all Buddhist rites. During the ceremony, the king first climbs up to the pedestal, cleans the image by wiping away any dust with a wet cloth, and changes the gold headdress of the Emerald Buddha. The king then worships nearby while an attendant performs the elaborate ritual of changing the rest of the decorative garments. The king also sprays holy water, which is mixed with the water rinsed from the wet cloth used to wipe the dust of the image, upon his subjects waiting outside the ordination hall. Previously this was a privilege afforded only to the princes and officials who were attending the ceremony (uposatha) inside the ubosot.

Ceremonies are also performed at the Emerald Buddha temple at other occasions such as Chakri Day (6 April 1782), a national holiday to honour the founding of the Chakri dynasty. The king and queen, an entourage of the royal family, as well as the prime minister, officials of the Ministry of Defence and other government departments, offer prayers at the temple.[4]

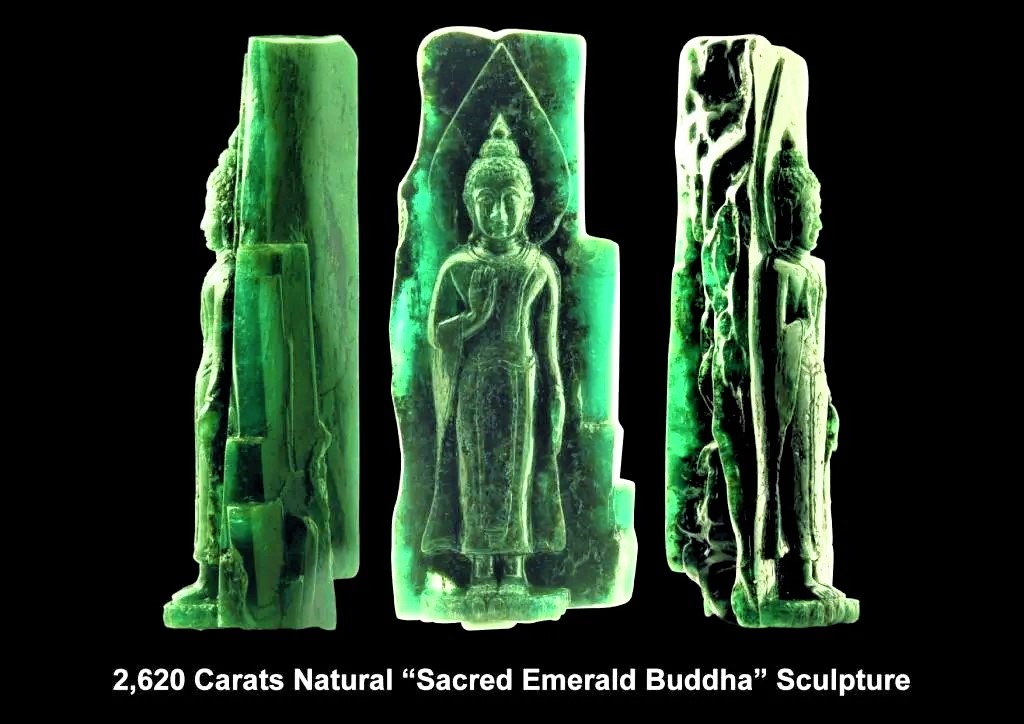

It is also interesting to note that an extremely special discovery in 1994, a 3,600-carat natural emerald crystal was discovered in Africa, although the exact country of origin has been disputed, with possibilities ranging from Madagascar to Zambia. By September of 1994, the large gemstone arrived in Thailand in search of a suitable buyer. Upon the crystal’s arrival, one astute gem dealer realised this was a very special stone. He wanted to maximize its potential rather than break it into smaller pieces as other competing dealers desired. After several months of intense negotiations, he finally won out. Hence began a quest for the best subject matter and design for this potentially world record-breaking emerald crystal. After extensive research into the history and art of Buddha images, the classic standing Buddha posture known in Thai as Harm Yhard emerged as the most appropriate choice. Traditionally, this was the Buddha’s admonition to his family members to stop quarrelling amongst themselves. The world suffered a great loss when Taliban extremists destroyed the giant standing Buddhas of Bamiyan, Afghanistan in 2001