The Forgotten Bedouin Palestinian Herders

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 12 Feb 2024

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

“Indigenous communities throughout the world are being increasingly marginalized and face the danger of imminent extinction. This is the stark reality facing the Palestinian Bedouin Herders, who not only have to confront the challenges of the 21st century rapidly encroaching upon their traditional lifestyle, but also the Jewish settlers invading their ancestral land for the development of the Israeli government approved housing settlements.” [1]

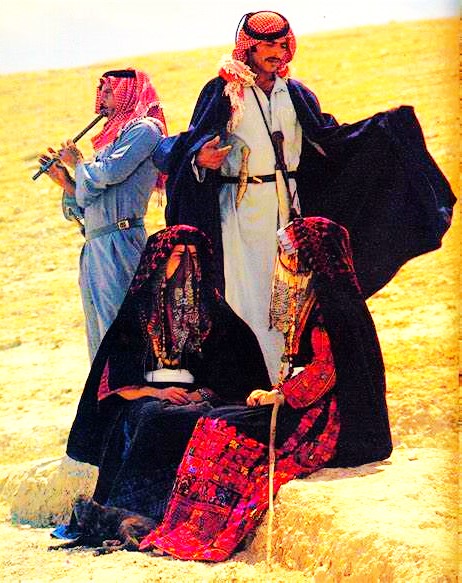

A colourised, vintage photo of a Palestinian Bedouin Tribal Herd Leader, attired in his traditional costume. Note the handcrafted headgear, belts and the sword, as a traditional weapon, carried by men of the tribe, the leader represents. The wealth of a particular Bedouin tribe is reflected by the number of livestock they possess. This cultural display and traditional attire is becoming increasingly rare, due to challenges of the 21st century.

This paper, discusses the Bedouin tribes of the Middle East[2] and highlights the challenges faced by these, nomadic, Indegenous communities throughout the troubled and worn torn region, with special reference to the Bedouin Herders of Palestine, who have noting to do with the geopolitics of the regions, but yet are caught up in the carnage of the War ON Gaza,[3] waged by Israel under the brutal government of Netanyahu’s[4] “scorched earth policy”, in the region. In addition, these Bedouins who have lived on their ancestral land, leading nomadic existence for centuries are now seriously threatened not only by the challenges of modernisation[5] in the 21st century, but are faced with ongoing harassment and physical violence by the Israeli settlers occupying the pastoral land they used for millennia. These Bedouins ae becoming an increasingly rare species of the human community, about to become extinct, in a process expedited by Israeli settlers.[6]

Colourised photograph of a Traditional Bedouin Family in the Middle East

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The History and Distribution of the Bedouin Herders.[7]

The word “Bedouin” is derived from the Arabic term “badawī” (بَدَوي), which has uncertain origins, but a couple of theories on its etymology:

- From the Arabic root words ‘b-d-w’ (بدو) meaning “to be isolated/alone”. This could refer to the isolated, remote desert areas the Bedouin peoples traditionally inhabited.

- From the term “al-bādiyah”, used for arid open land or the desert/wilderness regions in which Bedouin tribes roamed and lived across the Middle East and North Africa.

- Potentially linguistically related to the Arabic “bidan” (بِدَن), meaning “without”. Refers to Bedouin existing without permanent settlements or habitats. Always traveling through the landscape.

- Associated with the word “abda” meaning “herder”. Relates to the tribal pastoral lifestyle of herding camels, goats and sheep as nomads across desert terrains for grazing and water access.[8]

In essence, “Bedouin” in Arabic signifies desert wild dwelling[9], isolated nomadic peoples moving with their livestock herds across vast barren and arid regions devoid of major permanent settlements or cities. They are masters of mobility in areas considered uninhabitable “wilderness” zones by most societies. The core linguistic meaning captures their resilience and adaptability to survive and thrive in terrains where others could not.

Bedouins are nomadic Arab peoples who have historically inhabited the desert regions of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA)[10] , for centuries, even prior to the Biblical times. Some key points about Bedouins:

- They are traditionally pastoral nomads, moving their herds of goats, sheep, and camels over large swathes of desert based on the availability of grazing lands and water sources. This lifestyle is known as a nomadic or tent-dwelling lifestyle.

- Major Bedouin groups include those found in the Arabian Desert, Syrian Desert, Negev Desert, Sinai Peninsula, and Sahara Desert, among other arid regions. Historically many Bedouin tribes migrated across borders seasonal in search of grazing.

- Their society and culture have been shaped by the demanding conditions of desert life. Survival has depended on close social organisation based around tribal and clan lineages. While the collective West and urban dwellers, look down upon, the Bedouins, as lower life forms, with no culture, they have, on the contrary, rich oral poetic, artistic, cultures, with demonstrable survival physiology, under the harshest climatic conditions and ethnomedical traditions, which the so-called civilised communities, have absolutely no concept of.

- Their mobile lifestyle and fierce independence often put them at odds with settled peoples and centralised governments who sought to tax, conscript or control them. Tensions persist in some areas, to this day.

- Bedouin lifestyles and living patterns have changed dramatically over the 20th century due to challenges like national borders, restricted mobility, land privatisation programmes, and desire for more stable incomes. Many Bedouin now have settled or partly settled lifestyles focused on livestock trade, agriculture or wage labour.

In essence, Bedouins are desert-dwelling Arab tribal peoples found across North Africa and the Middle East, whose traditional nomadic cultures, remain influential, even as lifestyles have changed in modern times. Their history and culture reveal much about human resilience and adaptation to harsh desert environments.

It is important to note that not all shepherds are Bedouins. The term “Bedouin” refers specifically to ethnic Arab tribal groups who have traditionally lived a nomadic desert-dwelling lifestyle raising livestock across parts of the Middle East and North Africa. Some key points:

- There are many other groups worldwide historically known as nomadic shepherds or pastoralists who migrate with animal herds but are not Arabs. Examples include Berbers in North Africa, Maasai in East Africa, Mongols in Asia, Sami in northern Europe and others. These have their own cultural identities and terms.

- Similarly, there are shepherds in places like Europe, Americas and elsewhere who lead more sedentary lifestyles guiding sheep/goats between set seasonal pastures rather than constantly wandering across wide undefined ranges tracking scarce desert vegetation and oases like classic Bedouin groups did. These are referred to by other names – shepherds, livestock farmers, transhumance pastoralists etc.

- Over the past century, many Bedouin groups have transitioned to more settled ways in towns, taking up farming or other livelihoods as mobility became constrained by modern borders, land policies etc. Yet they still retain a cultural identity linked to nomadic Arab desert heritage distinguishing them from other pastoral societies worldwide.

In essence, while the concepts overlap, the term Bedouin refers to ethnically Arab tribal-organized peoples from desert regions across the MENA region who developed a distinctive nomadic culture and identity over centuries to thrive in arid landscapes too harsh for most other groups. This sets them apart from sedentary shepherds or non-Arab nomads globally. Components of traditional lifestyle remain embedded in Bedouin community memory today. In respect of other, global, nomadic communities, the Romani and Gypsy peoples share some key traits with the Bedouins, but originating out of the Indian subcontinent instead of the Arabian region. Some parallels:

- Like the Bedouins, Romani[11] form distinct ethnic groups scattered but related across diverse countries. And both traditionally maintained nomadic pastoral-type lifestyles combined with providing trade services as they migrated between areas.

- Their minority status, frequent exclusion from rights, and persistence of mobility-based livelihoods despite pressures to better ‘integrate’ or settle into mainstream state policies offers poignant similarities.

- As ethnic groups originating from elsewhere now woven across global regions without homogenous national states of their own, both face issues retaining coherent cultural identity as diasporic peoples while adapting in foreign lands.

- Both groups have endured long legacies of discrimination or ethnic stereotyping due to apparent “otherness” from more rooted, established surrounding populations in lands they traversed.

However, key contrasts also exist, as the Romani language and backgrounds derive from India not the Arab world as with Bedouins. Cultural markers around issues like religion also differ substantially. Lighter skin permitted Romanis potentially more flexible assimilation over time.[12]

While sharing the collapse of traditional crafts/caravan trades under modernity, plus problems securing rights without firm national bases, the Romani and Bedouins represent culturally distinct nomadic diasporas opening thought-provoking avenues around long-term adaptation.

The origins and history of the Bedouin peoples stretch back thousands of years:

Ancient Origins:

- There is evidence that a pastoralist desert lifestyle on the Arabian Peninsula dates back at least to the Nabatean kingdom based in Petra from 312 BCE to 106 CE[13]. The Nabateans conducted trade across the desert regions.

- Nomadic peoples traversed the arid expanses of the Near East and northern Arabian region mentioned in ancient texts as far back as Assyrian times in the 9th century BCE.

Biblical Times:

- Bedouins are referenced multiple times in the Bible and other Judeo-Christian texts, often called “Ishmaelites”[14]. Biblical depictions describe them as tribal nomads and skillful warriors.

- Historians believe Bedouin tribes inhabited desert oases, grazing lands and trade routes that crisscrossed Canaan, Jordan, Sinai and Northwest Arabia regions during biblical events.[15]

On a matter of religious genealogy, the question raised is that, were Jesus, Moses and Muhammad, Peace Be Upon Them All, born to a respective Bedouin family, historically? [16]Based on available historical evidence and scholarly consensus:

Jesus – Was not born into a Bedouin family. According to canonical Biblical scripture and other textual sources on the life of Jesus, he was born in Bethlehem to a family from Galilean Jewish lineages native to the region of Judea and areas within the Levant. No clear Bedouin connections are documented.

Moses – Uncertain links to Bedouins. While the Book of Exodus depicts Moses leading the Hebrew peoples out of Egypt through the Sinai desert after liberation, scriptural details on his family origins are vague. Potential theories exist tying Midianite tribes involved to Arabian proto-Bedouin groups. But concrete verification remains elusive.

Muhammad – Also shows no verified direct Bedouin lineage, but strong cultural affinities. Islamic texts like biographic Hadiths detail Muhammad’s early life in the urban trading center of Mecca with ties to the prominent Quraysh tribe[17], although tribal nomadic caravan commerce and associated Arabian oral traditions fundamentally shaped the landscape he was born into. Some ancestors were desert-dwelling, but he cannot be ethnographically classified as born into a Bedouin family strictly speaking based on current evidence.

Therefore, available documented histories of the patriarchal Abrahamic prophets do not conclusively confirm traces of Bedouin family lineages. But in the cases of Moses and Muhammad, broader imprints of enduring tribal nomadic cultures intrinsic to ancient Near Eastern/Arabian societies remain visible influencing the seminal Biblical and Quranic events conveying the foundations of Judaism, Christianity and Islam today. Bedouin traditions were profoundly impactful, but indirectly so. However, the depiction of Jesus as a shepherd in religious iconography and writings is primarily metaphorical, referring to his role as spiritual guide to humanity rather than literally meaning he herded livestock.

The “Good Shepherd” motif stems from several Biblical passages where Jesus describes himself caring for his “flock” of followers or disciples. For example (from John 10:11[18]):

“I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep.”

Here the metaphor serves to emphasise devoted protection and self-sacrifice in shepherding souls towards salvation.

While scripture has no record of Jesus practicing animal husbandry[19], calling him “shepherd” powerfully cements spiritual connotations of loving leadership safeguarding the righteous path. This explains the prevalence of pastoral shepherding imagery in historical Christian art regarding Jesus.

However, some scholars do speculate the parable could also reference contextual realities of Judaean working lifestyles. But ultimately the intent was delivering metaphysical resonance, not ethnographic commentary. Depictions of Jesus as a shepherd is aimed primarily towards unpacking theological guidance purpose over any biographical detail. The deeper spiritual meaning took precedence.

Challenges Over Time:

- Bedouin lifestyles have been impacted by wars, border restrictions and land/water access issues. 19th and 20th centuries, colonial boundaries disrupted traditional grazing patterns.

- Sedentarisation[20] (forced settlement programmes) under governments over the past century has radically altered Bedouin mobility and cultural identity in many nations.

- Today issues like land/housing discrimination, citizenship restrictions for migrants, religious/ethnic tensions, and loss of grazing lands pose ongoing hardships for Bedouin groups across the Middle East and North Africa.

The Bedouins as desert nomads have inhabited the arid expanses of the Near East and Arabia for millennia through a resilient tribal culture, but presently face marginalisation and survival struggles persisting into the modern age. Their rich history reminds us nomadic peoples have ancient roots going back to biblical-era and classical antiquity.

The pre-Abrahamic religious beliefs and practices of ancient Bedouin[21] peoples are not very well documented, but some insights can be gleaned:

- As nomads living in tribally-organised groups, Bedouins would likely have followed belief systems involving animism, polytheism, ancestor worship, and other common elements found globally in tribal indigenous religions.

- Worship often focused on supernatural elements/deities related to critical needs, those associated with fertility, longevity, rain, seasonal changes, astrological bodies, protection in the harsh desert climate, etc.

- Tribes held unique customs tied to major events – birth, transitions to adulthood/marriage, death, to cement social bonds and tribal identity. Ritual animal sacrifice was likely common.

- Adherence to codified religious scriptures and texts would have been unlikely, with spiritual/mythical traditions instead passed orally over generations. Rituals adapted locally.

- Ancient Bedouins left little or no written evidence themselves during the pre-Islamic times. But later Muslim writers sometimes classified Arabian tribal groups of pre-Islamic times as “pagans” or “idolators”[22], terms which carried negative connotations.

Ancient Bedouin faiths revolved around animistic, ancestral and polytheistic folk religions tailored to desert life prior to the shift towards monotheistic faiths like Judaism, Christianity and later Islam. Their flexible spiritual worldview allowed survival under harsh nomadic conditions. Lacking written histories, tracing precise origins/worship proves difficult. But ethnographic studies confirm indigenous belief systems dominated.

Given the harsh desert climate and challenging nature of a traditional Bedouin nomadic lifestyle, leisure time was more limited historically:

- Oral storytelling was a prime leisure activity around campfires, with poetry and fables recited among tribes to pass time, educate, and build cultural traditions.

- Music and singing using traditional instruments like drums and stringed ouds have long been important cultural expressions during rest periods or celebrations. Dancing and feasts accompanied music.

- Smoking various forms of tobacco, like shisha pipes, was common, as tobacco was one of few plants growing in the desert that could be used recreationally.

- Handicrafts[23] such as weaving, textile-making, leatherworking, jewelry, metal tool-crafting occupied leisure hours (often for women). These not only passed time but allowed creation of functional cultural art.

- Camel or horse racing occurred for both recreation and competition among tribes. Much prestige could come from breeding the fastest racing animals.

- Resting in the shade during intense daylight hours due to extreme heat was, and still is common during peak hot seasons where day work is avoided.

In modern times:

- Satellite TV, video games, electronics are now more accessible even in remote encampments, with solar equipment adopted. So digital entertainment also fills leisure time.

In essence, oral culture, handicrafts, celebrations and resting during intense heat fill Bedouin leisure time, though modernity provides some new digital options. The harsh desert climate historically made extensive free time quite rare.

Bedouins have developed remarkable ethnomedical knowledge and remedies to treat snake or scorpion bites and other medical emergencies, despite lacking access to modern healthcare, even deep in desert environments. Some traditional techniques include:

- Oral history and folk knowledge of indigenous flora/fauna means Bedouins[24] often expertly recognize dangerous species and symptoms of different venomous bites and stings.

- Immediate first-aid includes techniques like constricting blood flow, suction/removal of venom when possible, cauterizing wounds with hot coals, and quickly killing then eating the raw flesh of the snake/scorpion in hopes of absorbing antivenom.

- Herbal antidotes derived from local desert plants thought to have curative powers or counteract poisons are ingested, made into pastes for wounds, or boiled into medicinal teas, techniques passed down for generations.

- Bloodletting via cutting skin then using suction cups is believed to extract toxins from snake/scorpion bites in some Bedouin groups. Ritual animal sacrifice for healing also occurs.[25]

- Spiritual healing rituals involve shamans, animal sacrifices, symbolic dances and trance states to treat snake and scorpion bites believed caused by supernatural forces like jinn or curses.

- In serious cases, victims would be stabilised as best as possible in tents/camps while awaiting potential long transports to cities for hospitalization.

Bedouins have had to cultivate an impressive array of ethnomedical and improvised techniques tailored to surviving solely in remote desert wilds when bitten by venomous wildlife and lacking access to clinics [26]. Though emergency access and care has improved recently in some regions as more Bedouins settle.

The Bedouins of Palestine

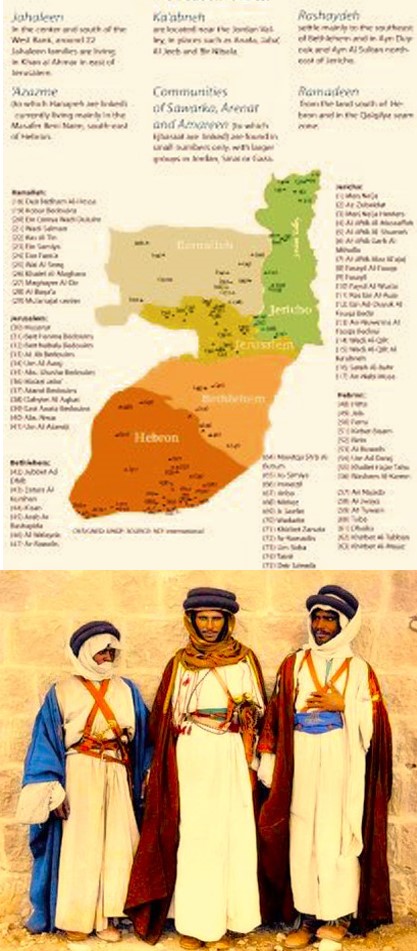

Photo Top: The geographic distribution of the different Bedouin Tribes of Palestine

Photo Bottom: Colourised Picture of leaders of Bedouin Tribes, attired in traditional costumes. circa 1900

The Bedouin Tribes[27]

The modern Bedouin tribes found today across the desert regions of the Middle East do have absolutely no verified ancestral or ethnic connections back to the Twelve Tribes of Biblical lore stemming from the prophet Jacob and his twelve sons as described in Judaic and Islamic scriptures. They are completely separate groupings.

The Twelve Tribes as depicted in the founding stories of Judaic culture refer specifically to the original Israelite confederacy of Semitic clans forged over centuries following the exodus hardships faced under the guidance of prophets like Moses and Aaron during the departure from Egypt towards the Holy Land.

In contrast, the emerged later on from localized Arab tribal nomadic groups indigenous to Arabia and surrounding desert regions with bloodlines and lineages tracing back to different progenitors.

In summary, while both enduring desert-based tribal ethnic subgroups, the ancestral origins of contemporary Bedouin tribes are decisively unlinked to the Twelve Tribes of Mosaic biblical tradition.

There are several main Bedouin tribes that have traditionally inhabited different regions of Palestine. Some of the major ones include:

- Jahalin Bedouins[28] – Originally nomadic shepherds from the Negev desert. After 1948 displacement from Israel, they resettled around East Jerusalem and the E1 area of the West Bank with livestock herding focus. Face high risk of displacement by settlements today.

- Ta’amra[29] – Largest Bedouin tribe in Palestine, based northeast of Bethlehem. Village agriculture and pastoralism maintaining strong tribal social framework and customs. Known for embroidery handicrafts and traditional poetry.

- Azazme[30] – Centered around the hills of the southern West Bank. Semi-nomadic herders today moving seasonally between village homes and grazing lands. political activism against Israeli land confiscations has been notable.

- Arab al-Rashaida[31] – migrated from the Sinai and Negev, now scattered small communities exist around Hebron and the Judean desert’s edge. Known for brightly coloured woven dresses. Speak a different dialect from other tribes.

- Arab al-Jahalin[32]: Originally dwelled throughout the Jordan Valley before many were forced into the Judean Desert after 1967. Extreme poverty and denial of infrastructure services in areas like Khan al-Ahmar.

While sharing common Bedouin heritage, the different tribal groups have distinct dialects, traditional territorial ranges, handicrafts, activism histories, facing varied current challenges tied to geography and Israeli policies pressuring communities since 1948. But overall nomadic pastoralism lifestyle remains deeply ingrained in culture and identity.An overview of some of the notable traditional crafts and art forms specifically associated with the major Bedouin tribal groups found in the Palestinian territories:

Jahalin Bedouins:

- Intricate beading art for decorating women’s dresses, jewelry, camel decorations

- Basket weaving using desert date palm fronds

- Herbal medicine preparations from indigenous plants

Ta’amra Bedouins:

- “tatreez” colourful cross-stitch embroidery featured on dresses, cushions etc.

- Al-Mafjar handwoven textiles with striped geometric patterns

- Crafting ibex horn jewellery and ornaments

Azazmeh:

- rugs and carpets with symbolic motifs woven from goat/sheep wool

- palm fiber baskets and mats

- camel leather bags and waterskins

Arab al-Rashaida:

- Brightly coloured patched dresses with coins decoratively embroidered

- Wool rugs with zigzag/diamond patterns

- Silver jewellery crafted by village smiths

Across groups:

- Glass/ceramic bead work featured on headpieces and garment trim

- Goat hair tent weaving knowledge

- Henna tattooing arts

So rich and diverse artisanal heritage exists – although much now threatened by displacement and craft knowledge not being passed on effectively amidst political turmoil and declining market viability. Cultural preservation is crucial. The Bedouins have adapted their living spaces and cultural expressions to the demands of a mobile, nomadic existence in the desert. Here are some details on traditional Bedouin rock art and housing:

Bedouin Rock Art[33]

- Petroglyphs and rock drawings dating back thousands of years found carved into remote desert rocks and cliff faces across the Middle East.

- Motifs depict tribal life including livestock, hunting, vegetation, mythology. Drawn for decoration, communication, storytelling, spiritual rituals.

- Styles vary across tribes/regions – from very simple engraved shapes of people, animals, weapons to elaborate multi-colour paintings in some areas like Libya’s Acacus Mountains.

- Rock art offers archaeologists insights into ritual practices, cultural symbolism, and ways of life that left few written records otherwise. Still being discovered today.

Bedouin Homes[34]

Housing is easy to transport – low squat tents woven with goat hair provide cool shade, rain protection. Divided interior spaces.

- Tents can be quickly broken down as camel-based caravans move seasonally across vast distances searching grazing/water.

- Modern permanent settlements now more common, but tents frequently pitched nearby to house livestock. Concrete block houses also built, but decorative tents erected beside for cultural identity.

Rock paintings reveal how Bedouins decorated shelter areas and culturally recorded history for generations. Portable woven tents still symbolise the flexible, transitory ethos central to being Bedouin, whether nomadic or settled. Home is adaptive space allowing group survival under the harsh desert sun and extremely dehydrating climate.

There has been substantial intergenerational loss of traditional Bedouin cultural elements, especially among youth migrating to cities instead of continuing pastoral or nomadic lifestyles:

- Factors like drought, lack of governmental support, and desire for amenities in cities have enticed younger generations to abandon the harsher tribal desert existence of their parents and ancestors.

- Bedouin literacy rates lag national averages across MENA countries. Some parents themselves push children to pursue urban education and careers rather than continue perceived ‘backward’ ways.

- Traditions like folk music/poetry, textile-weaving, nomadic herding skills are threatened as elders with such knowledge pass on. Cultural identity for those assimilating urban life frays.

- Sedentarisation programs have forcibly settled some tribes transitioning them abruptly from highly mobile ways, rupturing cultural continuity between generations.

- Modern legal constraints and border restrictions prevent migratory grazing patterns used for centuries. Climate change disrupts natural cycles relied on.

However, there are some pushbacks:

- Cultural groups using workshops, festivals try preserving threatened Bedouin heritage, teaching youth arts, music, medicines etc. of their ancestors.

- Some governments now recognize cultural losses. Steps taken for national non-material culture protection programs, heritage site recognitions.

In fact, the point about the next generation abandoning traditional desert tribal ways in favour of urban life is extremely prescient. Concerted efforts by both Bedouin communities and governments are vital to record and sustain ancient indigenous knowledge and culture being lost. More creative transitional programmes, balancing modernisation with heritage preservation are acutely needed. The gold and silver coins traditionally worn by Bedouin women on their face veils or headpieces are linked to specific tribal heritage and cultural identity markers. Some key details:

- The coins are known as “al-shadfa”[35] or “al-morqoa” in Arabic. They are often inheritance pieces made from gold and passed down between women of the family across generations.

- Affixing them to veils or headbands is a long-standing traditional practice particularly associated with Bedouin tribes in the Sinai peninsula and the Levant region.

- The coins signify tribal honour, marital status and respectable womanhood. New brides often receive coins from their mothers/grandmothers which they’ll then pass to their own daughters later.

- Older historical meanings tie the coins to superstitions around warding off poverty or the “evil eye”.[36] But today wearing them expresses cultural pride and preserving identity against disappearance more than magical beliefs.

- With declining numbers of Bedouin women donning face veils, the coins remain an iconic marker of enduring tradition and respectability even if married women adopt modern dress otherwise in daily life.

While the custom has evolved, the passed-down gold tribal coins hold deep social importance and sentimental value to Bedouin women as heritage keepsakes conveying identity and self-worth. The elegant glinting sight remains a distinctive cultural statemen

Comprehensive statistics on Bedouin demographics and health profiles are hard to come by due to their nomadic lifestyles, dispersion across many national boundaries, and lack of close monitoring by most MENA governments. However, I can provide a broad overview of available data as well as highlight some key socioeconomic and human rights issues:

Bedouin Demographic Statistics[37]

- Fertility Rates are typically higher among Bedouin groups compared to wider regional averages, though reliable recent data is scarce. Most recent birth rates found were between 4 – 7 children per Bedouin woman on average.

- Average Life Expectancy is estimated to be about 10 years lower for Bedouins (around 60-65 years) compared to non-Bedouin citizens in the same MENA countries, a notable gap likely tied to poorer access to healthcare.

- Infant/Child Mortality Rates also lag the averages for their resident nations – again by 10 or more additional deaths per 1000 live births among Bedouin children in most studied areas.

Socioeconomic Issues[38]

Today there are four major issues affecting Bedouin society: (i) large economic gaps and economic development efforts, (ii) an ongoing land dispute with the state, (iii) internal dilemmas around modernization, culture change and community development.(iv) Attacks by Israeli settlers and prejudices by the Israeli government as well as the Western, White, neo colonialists and racist imperialists.

- Many Bedouin groups face discrimination, exclusion, and restrictive citizenship policies depending on their country of residence currently. This creates barriers to health services, legal protections, education, employment. Statelessness issues have arisen for some.

- Reports of unfair land appropriation by governments or private interests, forced community relocations/settlement, and violent clashes seeking to dominated Bedouin inhabited areas continue periodically across several MENA nations.

- Poverty levels are high in many Bedouin communities today with shifts away from subsistence tribal living yet without the proper modern resources in place. Reliable income sources are a key problem.

The limited available data shows poorer health outcomes and socioeconomic equity issues adversely affecting Bedouin groups – but more comprehensive ethnic-line health statistics coupled with culturally-aware policy changes remain hugely needed from MENA governments to rectify human rights gaps. MENA is an acronym that stands for “Middle East and North Africa”. So MENA refers to a large combined region stretching from Morocco to Iran, covering the Arabic-speaking countries of the Middle East as well as the North African countries located along southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea.

In more detail:

- Middle East in this context includes nations on the Arabian Peninsula (Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman etc) plus Levantine countries like Jordan, Iraq, Syria; Egypt, and territories like Palestine.

- North Africa here includes the five northernmost countries – Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt (which spans both Middle East and North Africa).

- Some definitions also include Sudan, South Sudan, Turkey, and Iran when using the MENA acronym given proximity and shared aspects of history/culture.

MENA serves as a common geographical and geopolitical shorthand to refer to the broad, culturally interconnected region spanning the deserts and coastal civilizations across the Middle East territories and countries in the northern half of Africa. Grouping them under the MENA umbrella is convenient for discussing history, economics, travel or issues like the Arab Spring affecting several countries across this large transcontinental zone.

The country with the largest Bedouin population in the world is Egypt. According to estimates, Egypt has around 1.5 – 2 million Bedouins residing within its borders, primarily concentrated in the Sinai Peninsula and Eastern Desert regions.

The Egyptian Bedouins represent around one fifth of the total global Bedouin population, which is estimated to be between 7-10 million people living across the Middle East and North Africa regions combined.

After Egypt, the countries containing sizable Bedouin populations include:

- Jordan: Over 1 million Bedouins make up important components of Jordanian society and political elite. Many were integrated from Saudi Arabia or surrounding nations.

- Saudi Arabia: 900,000+ Bedouins inhabit the vast desert hinterlands. Pressures from Saudi oil extraction and infrastructure sectors have impacted grazing lands.

- Syria: Roughly 500,000 Bedouins resided in Syria before civil war turmoil displaced communities. The richest pastoral lands lie in east.

- Libya: Perhaps 450,000 Bedouins call Libya home, with best known groups including the Fezzan and Cyrenaican Bedouin having rich cultural traditions.

As the largest Middle Eastern country spanning the crossroads between North Africa and the Horn of Arabia, Egypt contains the greatest number of indigenous Bedouin peoples identifying as part of this unique desert-dwelling ethnolinguistic group. The Egyptian Sinai and Negev remain quintessential Bedouin heartlands.

The Negev Desert is located in southern Israel, covering over 60% of Israel’s land area. So in terms of current geopolitical control and administration:

- The Negev Desert is part of sovereign Israeli territory, with the Negev comprising the southern administrative district of Israel.

- The largest city located within the boundaries of the Negev desert region is Beersheba, which serves as the capital and economic center of the broader Negev district.

However, there have been some disputes regarding land rights and autonomy involving the Negev Desert[39]:

- Many Bedouin Arab tribes have inhabited and grazed lands within the Negev Desert for centuries. After the formation of Israel in 1948, many Bedouin communities were relocated or restricted into designated zones, creating tensions over indigenous land ownership that continue today.

- There are still several “unrecognised villages” dotting the Negev which lack full infrastructure and government services because their legality has not been formalized under Israeli administration. This also applies to some Bedouin townships.

In practical sovereign terms, Israel administers the Negev Desert through its southern Negev administrative district. But disputes over the treatment, land access, and cultural autonomy of the historically semi-nomadic Bedouin Arab residents remains an issue of tension and debate in this hotly contested region. Balancing growth, resources access, and indigenous rights continues to pose challenges in the sensitive geopolitical ecosystem of the Negev.

there is a sizable Bedouin population living within Israel’s borders, mainly concentrated in the southern Negev desert expanse. There is also a much smaller Bedouin presence in Palestinian administered areas. Some key details:

Bedouins in Israel[40]

- Around 300,000 Bedouins live in the Negev Desert including within officially designated towns/villages as well as informal “unrecognized” encampments lacking infrastructure.

- Around 60,000 live elsewhere in Israel outside the Negev region, mostly integrated within other cities/towns.

- Bedouins are full Israeli citizens entitled to vote, however community activists have highlighted systematic discrimination in access to land, housing, basic services both in the Negev communities and broader society.

Bedouins in Palestinian Areas[41]

- Populations far smaller – an estimated 72,000 Bedouins lived across the West Bank and Gaza Strip regions as per the Palestinian Authority’s 2016 census, concentrated around Hebron, Bethlehem and East Jerusalem outskirts.

- Most are officially registered Palestinian residents holding ID cards though Israel never fully recognized many villages after 1967 occupation. Rights groups say this leaves communities stateless without basic amenities and under threat of displacement by settlement expansion.

Indigenous Bedouin peoples who were traditionally nomadic do reside within both Israel and Palestinian administered areas, but face varying degrees of citizenship rights, discrimination in practice, and pressures from policies undermining traditional lifestyles especially with regards land usage and mobility restrictions upon communities stretching back centuries.

The Broader Societal Importance of the Bedouins[42]

1 Regional Societal Impacts

- As nomads crisscrossing the deserts, Bedouins have for centuries connected settled towns/oases via trade routes and transportation caravans. This encouraged economic and cultural exchange.

- Tribal social structures and survivor skills adapted to the harshest landscapes provide lessons for resilience. Bedouin values of hospitality endure in many MENA societies.

- Knowledge of desert ecology and species exists within Bedouin traditions, offering insight on sustainable land use for development interests in arid areas.

2 Risks if Bedouins Die Out

- The rich cultural memory bank and reservoir of desert wisdom built over thousands of years would disappear before being fully tapped by modern societies.

- In some regions, loss of nomadic grazing herds allows dunes and aridity to overwhelm oases, reducing scarce arable land.

- An intangible but vital link connecting urban and rural habitations nourishing collective heritage is severed.

3 Legacy

- Iconic Arab folk arts like poetry, music, and textile-making trace origins to Bedouins.

- Camel domestication and selective breeding in Arabia arose from Bedouin lifestyles.

- Ancestral mobility patterns and spatial knowledge have left imprints on trade networks, pilgrimage routes, and city locations.

4 Economic Impact

- Bedouin groups attract cultural tourism in some wealthier MENA nations. However, overall, most Bedouin communities remain quite marginalized from national prosperity.

- Smuggling networks for goods, weapons etc thrive in peripheral deserts partly thanks to Bedouins’ mobility and infrastructure knowledge. But this represents survival responses to poverty/conflict more than economic leadership.

In essence, from archetypal cultural attributes to geopolitical connectivity to environmental equilibrium, the disappearance of enduring Bedouin heritages risks erasing a vital backbone subtly underpinning many MENA societies in absence of vigorous heritage safeguarding.

many MENA governments over history have harboured hostility or negligence towards the Bedouins as nomads living outside the norms of centralized statehood:

- Sedentarisation policies sought to forcibly settle Bedouins in towns, restrict mobility to monitor/tax them better. This clashed with pastoral needs.

- Land privatisations allocated customary tribal grazing commons to outside development interests, displacing communities and fuelling clashes over deeds.

- Discrimination is common denying Bedouins equal citizenship rights and access to state resources/services as ‘outsiders’, leading to socioeconomic marginalization.

- Military control tactics try limiting Bedouins’ movements especially in border zones or restive areas. Settlements without tribal approval raised tensions.

- Cultural practices like tribal justice codes were often banned by states wanting monopoly on law and order. Language and attire restrictions occurred under nationalism.

Key Root Causes

- Bedouin autonomy and mobility across expansive lands is inherently harder for distant rulers to assimilate into the machinery of government compared to sedentary peasants.

- Orientalist prejudices permeated colonial attitudes deeming pastoral nomads as ‘primitive’ and suspicious compared to elite urban societies. Dusty reality belied romantic literary exoticism.

So in summary, the flexible migratory lifeways central to Bedouin ethnic identity have been repeatedly stigmatized and suppressed over recent centuries under centralized MENA states as unwieldy to national consolidation and ‘civilizing’ visions. Transforming this fraught relationship requires profound policy shifts.

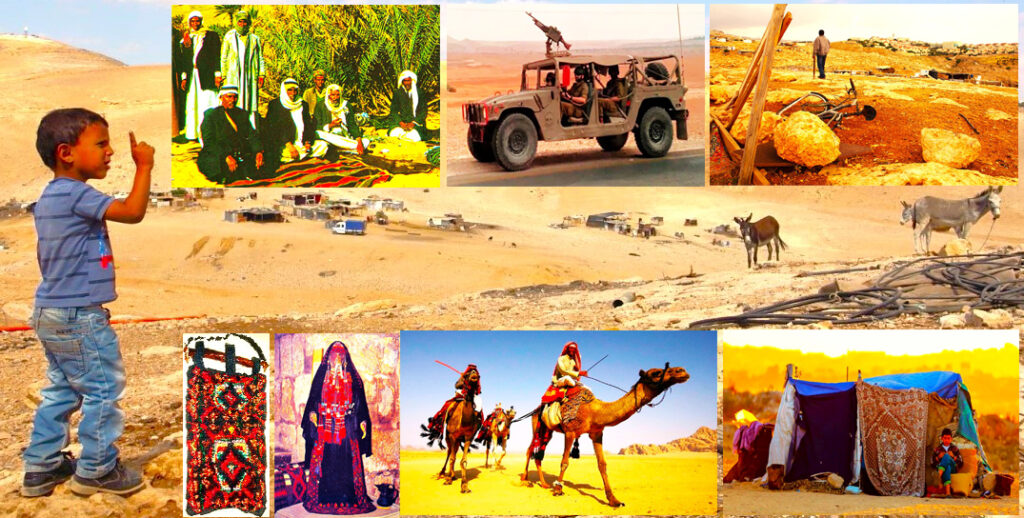

A photo collage of the contemporary Palestinian Bedouin Shepherds’ Lifestyle as well as internal and external challenges faced, by these nomadic communities.

Main Photo: A Palestinian Bedouin general grazing settlement showing the donkeys, as a mode of conveyance of goods and transport, with the tribal settlement in the background. The picture is dominated by a Palestinian, Bedouin child, attired in contemporary modern dress code, indicative of a dying Bedouin culture and ancestral traditions, dating back many millennia.

Inset Photos bottom from left to right: Example of traditional, handwoven, intricate wall decoration made from woven, dyed wool, in bright colours, incorporating traditional patterns. Bedouin lady in traditional tribal attire. Note the head piece and Islamic face cover, adorned with genuine gold and silver coins, reflecting the tribal wealth, as a family heirloom handed down from generation to generation. These jewellery pieces are often confiscated by attacking Israeli settlers, during ongoing skirmishes, buttressed by Israeli desert patrol forces. Camels used for long haul pastoral migration in the Negev Desert by the Bedouins. A typical Bedouin Tent, adorned with a traditional handwoven rug , outside. This could be offered for tourist as a tribal craft for sale to tourists. Which are increasingly rare and often a large percentage of this income is deducted by Israeli patrols, as extortion.

Inset Photos top from right to left: The aftermath of a Bedouin settlement attacked by Israeli settlers. Note the mangled bicycle and remnants of their tent dwellings, an all too common site in recent times. Often the Bedouins are killed in such attacks, with no accountability. Palestinians face frequent attacks from settlers in the occupied West Bank and the Negev Desert by heavily armed Israelis soldiers, ready to shoot first, at the slightest opportunity, at the Bedouins.

Photo Credit: Menahem Kahana /AFP/ Getty Images, Al Jazeera, Wiki Commons, AFP.

The relationships between the Palestinian Bedouins and Israeli settlers on original Bedouin lands in the Negev Desert[43]

The relationship between Israeli Bedouins and Israeli settlers in the Negev Desert has sadly been defined by tensions, discrimination, and at times open clashes related to contested land and water rights in the region. Since October 07th 2023, there have been 16 violent attacks on the Palestinian Bedouins, by militant Israeli settlers, who are now equipped with heavy arms supplied by the Netanyahu government, as a means to protect the settlers against Palestinian attacks. In reality, the widespread armed aggression is to kill as many Palestinian settlers who “do want war”[44] and has been on their ancestral land for millennia in the Israeli occupied West Bank. As of 07th October, there are approximately 500 Bedouin shepherds and 500,000 illegal settlers, who are expropriating the Sephardic ancestral land and terrorising these innocuous Palestinians in nightly raids, like the modus operandi of the IDF, attacking and conducting night raids on Gaza and civilian residents in the occupied territories, demolishing homes and committing other war crimes, in which the Biden administration, UK and Germany are certainly complicit. The entire philosophy is one of total annihilation of all people of Palestinian origins from the face of Gaza and the occupied territories, as clearly enunciated by the different, senior Israeli Ministers over the past years and emphasised further following the 07th October 2023, war on Gaza, in which the Hamas is trying to regain what rightfully belongs to them. These attacks on the Bedouin shepherds is a long standing aggression and have been have been in progress for many years. On 26th March 2023 a report appeared in the New Arab, that, a Palestinian herder was wounded and vehicles damaged in attacks by Israeli settlers in the occupied West Bank, according to reports. Palestinian drivers were attacked as they travelled through a junction near Nablus, local official Ghassan Daghlas was quoted as saying by the Palestinian Authority news agency WAFA. He said some vehicles were damaged, though nobody was hurt. Palestinian drivers were also attacked by stone-throwing settlers in the Jordan Valley, where Israeli extremists stopped traffic from going through the Al-Maleh junction, according to the official Mutaz Besharat. He also reported a settler attack on Palestinian herders in the Jordan Valley, in which one man was wounded after being struck on the head by a stone[45]. Palestinians face frequent attacks from settlers in the West Bank, incidents that sometimes turn deadly. Settlers went on a rampage in Hawara, a town near Nablus, following the killing of two Israelis. The attack saw homes and vehicles torched, with one Palestinian killed in a nearby town. Israeli forces and settlers have killed at least 90 Palestinians so far this year, an average of more than one a day. More than 700,000 settlers reside in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. Settlements are illegal under international law. When reports of attacks by the Palestinians are made to the Israeli police, they are biased and nothing happens, while the settlers return to terrorise the shepherds even more. One local shepherd leader spent nine hours at the police station, to no avail. These attacks have intensified as the war on Gaza is ongoing, with no peace in sight for the shepherds and their families.

On 27th January 2024, in Ein al-Hilweh, in the occupied West Bank, with two of his sons in prison and his cattle pens, his livelihood, all but emptied, Palestinian shepherd Kadri Daraghmeh,[46] 57, was beside himself. Inside their open-air tent, with no running water and minimal electricity, his sick wife fought back tears.[47] “My children are in prison, and every day it’s just more money I need to pay when we don’t even have money to buy food,” said a devastated Kadri. Kadri’s woes began to worsen dramatically last month. On December 25, he says, settlers stole 100 of his cattle in the night, released some cows near a road, and then called Israeli police. Cattle “roaming freely” is illegal under Israeli law, so the police confiscated the cows. Kadri was forced to pay 49,000 shekels ($12,900) to get 19 of his cows back. Kadri could pay only with the help of friends and Israeli activists. Kadri wanted to move on from the ordeal, but on the evening of January 7, two of his sons called to tell him they had been entrapped by a settler named Uri Cohen and arrested. Cohen contacted Jaser, 29, and Rihab, 19, and offered them a spot where they could graze their cattle undisturbed. It was an offer that was difficult to refuse. In the earlier days of the war, settlers, including those working for Cohen, had been attacking shepherds and their flocks with weapons, unleashing dogs or even scaring the sheep away with cars, and in more recent weeks such confiscations by authorities were on the rise. And “each time [there was an incident]”, recalled Kadri, “Uri would say: ‘Why do you need these problems? Sell your cattle to me.’” So Kadri’s sons decided to take up Cohen’s offer. But when they got to the spot, Cohen called the council inspector, a settler, who in turn called the police. Police came and cuffed the two men to each other and confiscated the 60 cows with them, for bringing the cattle onto “private land”. When he got the call, Kadri, his wife and two other sons, Luay, 31, and Basel, 27, rushed to help. As Kadri was protesting to Shai Eigner, a local settler who is a land inspector for the Jordan Valley Regional Council, a border patrol officer arrived, who shortly thereafter punched him in the face, making him bleed, and threw him to the ground. Spooked by the violence, Luay and Basel ran back to the car. Shouting at Kadri’s sons to stop, the border patrol officer began to shoot at the car.The Israeli officers arrested Luay and Basel and took them to the police station. Later, they were transferred to Ofer prison and then, a week later, to another prison. Basel was released after a week and a half, while Luay was released on bail after more than two weeks, accused by the border patrol officer of trying to run him over.Jaser and Rihab, who had brought the cattle, were taken to a remote area the night of January 7 by Israeli security personnel – and left there to fend for themselves. Kadri has been left with almost none of his cattle, his livelihood, and facing a 120,000-shekel ($31,600) bill he must somehow pay to retrieve the 60 cows the local settlement council is holding. The tab increases by 50 shekels per cow per day. Attacks and harassment from settlers and soldiers were happening before October 7, the day the Hamas attacks on Israel took place. But, Kadri says, this incident was the first time it was premeditated and coordinated. “This was the first time the settlers, the police and the army came together, like this, to make one fist,” he said. Facing insurmountable debt that only grows, Kadri and his family are beginning to see the writing on the wall: with increasing confiscations, restrictions, and now arrests and extraordinary fines, their way of life may no longer be feasible. Now, two of Kadri’s brothers are selling their cattle to an intermediary who will sell them to none other than Uri Cohen. A third brother is likely to follow suit. “The situation is very bad,” said a distraught Kadri. “No human rights, no justice. We want peace. We have no hate for anyone – Jewish, Christian, Muslim, Israeli, American, whatever. We have children, we want to live. But they make it so there is no future for us.” ‘They are working together in a way they hadn’t before’ The abyss confronting Kadri’s family also confronts most Palestinian shepherds across the Jordan Valley and much of Area C, a part of the West Bank that is under full Israeli military control. Many others in the area describe similar confiscations, detentions and restrictions by Israeli forces recently, often in conjunction with or carried out by settlers. Another incident similar to Kadri’s occurred two weeks later, in which Palestinian shepherds Shehda Dais and Ayed Dais in al-Jiftlik had their sheep taken by security personnel and were forced to pay 150,000 shekels to prevent their confiscation. The settlement council allegedly threatened the shepherds and six families from the community that they would be forced to pay 1 million shekels ($271,260) if they attempted to bring their flocks out grazing. For decades, the Palestinians of the Jordan Valley, which number approximately 65,000 according to rights group B’Tselem, have faced severe restrictions in access to critical resources such as water, 85 percent of which goes to settlers, though they number approximately 11,000 – a sixth of the Palestinian population – in the area. They are prohibited from collecting rainwater or accessing any water on their land. Kadri and his sons live along a spring that has been fenced off solely for settlers’ use. While all settlements are illegal under international law, the Jordan Valley at least had settlers who were relatively less violent in the past, and Kadri describes amicable relations with settlers once upon a time. But then the first Israeli settler outpost, illegal even under Israeli law, though in practice largely permitted by Israel and buttressed by its security forces, came in 2016, and attacks and harassment of shepherds have escalated since.

Albeit, some key aspects of the plight of the Bedouins are highlighted:

- Many Bedouin tribes inhabited parts of the Negev for centuries before the formation of Israel. After 1948, large areas were designated exclusively for new incoming Jewish agricultural settlements, displacing Bedouins without compensation.

- Bedouin villages have been repeatedly demolished and declared illegal by Israel over decades. Dozens still lack electrical power, water or healthcare access today, with permits denied for development.

- Settlers often see Bedouins as security threats or squatters on now state-owned lands. Security force and settler violence against Bedouins and livestock has occurred, stoking conflicts.

- Competing claims over vital underground water sources and aquifer-access between Israeli farms and Bedouin herders fuels economic and legal skirmishes with frequent biases against the politically weaker tribes through the court system.

- Calls for better integration of loyal Bedouins into Israeli society contrasts with demands for restoring indigenous land rights, self-governance and cultural protections – illustrating worldview gulfs.

In essence, while some cooperation efforts are emerging, the power imbalance allowed settlers to dominate choice Negev areas. Systemic inequities, active marginalisation of pre-existing land users, and cultural distrust plague positive relations currently – requiring profound shifts on recognition and restoration to mend. There are no effective strategies to reconcile these two groups in the future, noting that the numbers of Settlers are ever increasing, needing more land for domestic habitation, while the Bedouins are decreasing, in their original ancestral land and become a “rare ethnic, human species, about to become extinct”. growing gaps with major power/number asymmetries risks Bedouin cultural erasure over time. Survival would depend a lot on visionary reconciliation policies given current trends. Some ideas that could help deescalate long-term tensions include:

Suggested Strategies by the Author

- Formal truth and reconciliation efforts between Bedouin elders and settler communities to humanize perspectives and recognize harms inflicted on both sides historically. This can form bases for empathy.

- Negev-based intercultural schools, joint museum projects spotlighting diverse heritages of the region over the ages without politicization. Allows re-education on common humanity.

- Co-management of protected arid agro-ecology zones allowing sustainable integrative use of scarce desert resources like pastures, springs etc via traditional Bedouin ecological knowledge and appropriate advanced techniques without dislocation.

- Special priority zones created just for maintaining mobile Bedouin routes and grazing access within wider settler state lands. Rights enshrined in binding international indigenous accords.

- Apologizes Bedouin political quotas, affirmative policies for economic inclusion, streamlined citizenship and site improvements to signal national embrace of Bedouin identity within fabric of society.

The keys would be mutual healing of historical wounds, building cultural bridges through younger generations, carving out integrative use spaces respecting all heritage practices, and signalling renewed commitment to equitable belonging in deeds not just words. Positive future possibilities exist if creativity and goodwill mobilised.

The Bedouin, Livestock Economy[48]

Bedouins have traditionally relied on a mix of key desert-adapted livestock that offered both subsistence usage and important bartering value in their pastoral nomadic economy. These included:

- Goats & Sheep – Hardy hair-covered breeds could survive arid conditions providing milk, meat, wool, hides. Mainstay of nutrition and trade goods.

- Camels – Camel hair textiles, milk etc were vital. Camels unmatched as water-efficient “desert ships” carrying people/loads enabled mobility and commerce between tribes/villages.

- Donkeys – Small sturdy donkeys served as primary beasts of burden moving campsites. Dung as fuel. Milk in diets or medicine.

- Horses – Prestigious riding horses and breeding of famed Arabian racehorse lineages elevated tribe status. Valued trade commodity.

Barter long predominated trade – animals themselves and their products directly exchanged outside cash economies. Established “prices” for sheep or weavings existed locally based on effort, needs. Some standard weights of salt, tea, spices etc also served as informal currency. Cash came later as traders entered areas.

Modern Changes – With settlement, links to urban markets grew via trucks. Sheep/wool focus prevails where possible, camels now smaller role. Crossbred animals yield more, but cultural shifts mixing herding with other incomes or small business are now common to sustain families. Cash crucial nowadays.

Bartering a range of livestock varieties and artisanal items from them allowed Bedouin cultures to thrive without formal currencies for centuries, with intricate localized knowledge shaping values. Blending such deep heritages with globalised realities poses an immense modern challenge.

Official body representing the Bedouins, Romanis, Gypsies[49], Inuits[50], Metis, [51] and other “off the grid” indigenous groups to prevent their cultural genocide.[52]

There are official organisations that advocate for the rights of indigenous groups like the Bedouins, Romani, and others at an international level:

United Nations:

- At the UN, the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues serves as an advisory body to the Economic and Social Council specifically addressing the rights and concerns of indigenous peoples globally.

- Relevant UN agreements like the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples also uphold key protections for traditional land usage, cultural freedoms, self-determination etc.

- Special UN Rapporteurs closely monitor threats to indigenous groups worldwide, aiming to pressure governments over issues like forced assimilation, displacement etc through investigations and speeches.

Beyond the UN:

- Organisations like Cultural Survival, Minority Rights Group International, and the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization uphold advocacy and activism spotlighting indigenous rights issues globally at a non-profit level.

- Grassroots indigenous movements have also formed umbrella solidarity networks and coordinating bodies spanning groups from multiple countries. For example, the International Romani Union for Romani advocacy.

Therefore, rising awareness of shared risks to indigenous lifestyles is spurring expanded cross-group representation efforts, although impact remains difficult given still powerful assimilation pressures from states and corporations worldwide in practice under globalisation. Yet the activism offers important unity and signals against cultural erosion.

The Bedouin Intertribal Dynamics[53], [54],[55]

While Bedouin tribal groups have historically had occasional rivalries and disputes, they shared more predominantly aspects of cultural unity and some key particulars:

- Infrequent skirmishes occurred between clans or tribes, often over scarce grazing lands or water access rights. But as survival in the harsh desert required mutual cooperation attitudes of larger social cohesion prevailed.

- Intermarriages between larger tribal confederations also softened major hostilities as kinship lines crossed group boundaries while certain tribes held more spiritual prestige like lineages tied to Muhammad.

- The Arabic language and Muslim faith formed two foundational markers of a broadly shared social identity transcending tribal levels despite local dialect variations. Customary legal norms around hospitality, justice etc also aligned.

- No verified equivalencies exist between modern Bedouin subgroups and the Twelve Tribes tracing symbolic ancestry to the sons of Jacob mentioned in Jewish/Christian biblical tradition. Origin connections are unrelated.

Strong cultural commonalities cantering on language, faith, and customary law meant that a sense of overarching belonging to a Bedouin meta-identity endured between tribes even despite occasional land usage rivalries or petty disputes arising in strained desert niches. The harshness of desert life reinforced cooperation on fundamentals.

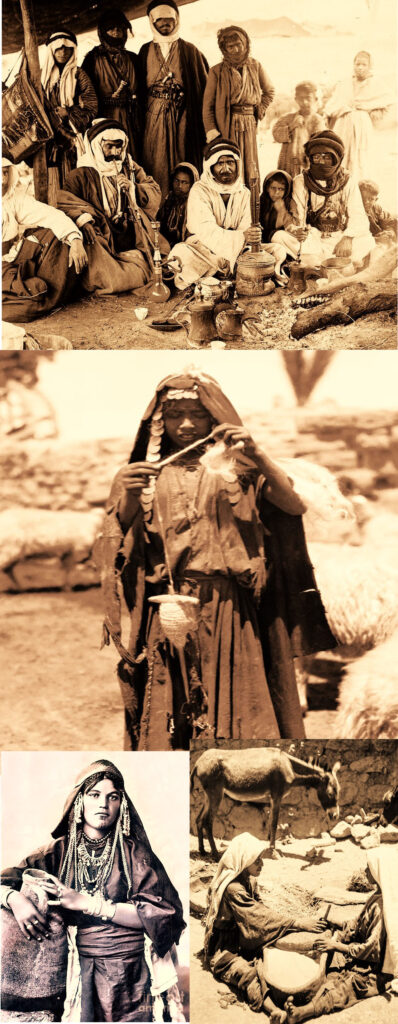

Vintage photos of the Bedouin Tribes and their traditional lifestyle

Top Photo: A Bedouin community with their Leader and slaves

Middle Photo: A Bedouin Women with wool taken from sheep in a traditional yarn reel, for weaving, rugs, clothing, tent material and carpets.

Photo Bottom left: Palestinian Bedouin Women in traditional attire Munir Alawi

Photo Bottom Right: Bedouin women grinding grain in traditional granite mill. Surrounded by mules, used for transport and milk.

Photo Credits: Wikimedia Commons. Circa 1900

The Bottom Line when it comes to the Bedouins is that their cultural survival faces major uncertainties in the future if no actions are taken. Some policy measures various MENA governments could implement to help preserve Bedouin heritage include:

- Legally designating Bedouin lands, routes, oases etc as protected indigenous territories and corridors. This secures space for traditional mobile grazing and prevents loss of ancestral lands to development.

- Funding special cultural programs like language revitalization, traditional skills teaching, storytelling festivals to pass endangered knowledge to Bedouin youth and build pride.

- Supporting Bedouin-led cooperatives focused on sustainable industries like handicrafts, ethno-tourism[56], niche food products. This provides livelihoods integrating with, not replacing, old ways.

- Joint management councils between tribes and governments to give Bedouins real decision-making power over policies impacting their communities instead of unilateral top-down control.

- Flexible models of schooling, healthcare and services delivery able to integrate with semi-nomadic movements if desired rather than forcing full sedentarisation.

- Reserved Bedouin political representation quotas to ensure governments heed their voices and special status as indigenous peoples during policy decisions on regional development.

- Human rights law protections explicitly defending distinctive Bedouin cultural freedoms related to mobility, land usage, language etc modelled off global best practices.

Contingency planning around flexible integration and hybrid lifestyles will be key, forcing stark choices between modernity and heritage makes assimilation inevitable.[57] Nuanced governance recognising Bedouins as unique indigenous cultures choosing which traditions to nurture forwards is vital for preservation. The key takeaways concerning the current situation and plight of Palestinian Bedouin tribes:

- Marginalised community with roots going back centuries facing cultural loss and displacement under ongoing Israeli land/settlement policies post-1948.

- Around 70,000 Palestinian Bedouins in scattered communities mainly near Jerusalem/Bethlehem, Hebron hills and the Jordan Valley now at risk.

- Israel deems habitats of many groups as “illegal” while denying requests for basic electrical, water, healthcare infrastructure for decades leaving dire poverty.

- Forced sedentarisation underway as pastoral mobility severely constrained by political boundaries, settlements, military zones and preserve areas limiting access.

- Traditional livelihoods like animal herding threatened without land access causing unemployment and cultural deterioration. Traditional skills not passing fully to new generations anymore amid upheaval.

- International rights groups decry lack of schools, imminent demolition orders, toxins and pressures to leave Palestinian Bedouin home areas under opaque relocation terms.[58]

In essence, the destabilised limbo of Palestinian Bedouins represents a complex long-term injustice toward vulnerable indigenous communities[59] with few easy resolutions given intractable land conflicts, requiring urgent moral attention and creative policy solutions to prevent complete cultural dissolution, as well as physical annihilation by the ongoing Israeli genocidal actions, against all Palestinians.[60]

References:

[1] Personal quote by author, February 2024

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bedouin#:~:text=The%20eastern%20Bedouin%20are%20camel,in%20time%20to%20practice%20agriculture.

[3] https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2023/11/29/egypts-sinai-bedouins-fear-israels-mass-displacement-of-gaza-palestinians

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/jan/13/israel-hamas-gaza-war-crimes

[5] https://www.jstor.org/stable/2536316

[6] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/10/20/silent-annexation-settlers-dispossess-west-bank-bedouins-amid-israel-war

[7] https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2023/10/23/israel-hamas-war-settlers-speed-up-eviction-of-palestinian-bedouins-in-west-bank-hills-amid-war_6195780_4.html

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pastoralism

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pastoralism

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_East_and_North_Africa#:~:text=The%20UNAIDS%20regional%20classification%20of,Arab%20Emirates%20and%20Yemen%22%2C%20according

[11] https://www.britannica.com/topic/Rom

[12] https://www.quora.com/Why-do-the-Romani-seem-to-assimilate-better-in-the-United-States-than-they-do-in-Europe-You-never-hear-about-crime-and-gypsies-in-the-U-S-but-people-in-Europe-seem-to-have-a-lot-more-issues-with-them

[13] https://study.com/academy/lesson/nabateans-history-culture-facts.html#:~:text=Between%20312%20BCE%20and%20106,parts%20of%20Arabia%20and%20Syria.

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ishmaelites#:~:text=The%20%22Arabized%20Arabs%22%20(musta%CA%BFribah,tribes%20of%20Otaibah%20and%20Mutayr.

[15] https://isac.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/shared/docs/ois5.pdf

[16] https://www.islamic-invitation.com/article/details/English/78/Moses-Jesus-Muhammad-Three-Men-One-Mission

[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quraysh#:~:text=The%20Quraysh%20(Arabic%3A%20%D9%82%D9%8F%D8%B1%D9%8E%D9%8A%D9%92%D8%B4%D9%8C),Hashim%20clan%20of%20the%20tribe.

[18] https://bible.oremus.org/?passage=John+10:11-16#:~:text=11%20’I%20am%20the%20good,his%20life%20for%20the%20sheep.&text=The%20hired%20hand%2C%20who%20is,snatches%20them%20and%20scatters%20them.

[19] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christianity_and_animal_rights

[20] https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/S%C3%A9dentarisation#:~:text=Les%20premi%C3%A8res%20traces%20de%20s%C3%A9dentarisation,dans%20le%20Croissant%20fertile).

[21] https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hccc-worldcivilization/chapter/culture-and-religion-in-pre-islamic-arabia/#:~:text=Before%20the%20rise%20of%20Islam,phenomena)%20possess%20a%20spiritual%20essence.

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Idolatry

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palestinian_handicrafts

[24] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344257752_INTEGRATING_BEDOUIN_INDIGENOUS_AND_SCIENTIFIC_KNOWLEDGE_FOR_LAND_RESOURCES_MANAGEMENT_IN_DRYLAND_AGRO-PASTORAL_AREANORTHWEST_COAST_EGYPT

[25] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1988790/

[26] https://www.britannica.com/topic/Bedouin

[27] https://www.greatvaluevacations.com/travel-inspiration/bedouin-tribes-of-the-middle-east

[28] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jahalin_Bedouin

[29] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beit_Ta%27mir

[30] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Azazima

[31] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rashaida_people

[32] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%27Arab_al-Jahalin

[33] https://www.csmonitor.com/Science/2019/1127/In-Jordan-s-desert-ancient-rock-art-finds-modern-defenders

[34] https://factsanddetails.com/world/cat52/sub331/item1987.html

[35] https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=the+coins+are+known+as+%22al-shafa+bedouin+coins+value&qpvt=the+coins+are+known+as+%22al-shadfa+bedouin+coins+value&FORM=IGRE

[36] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evil_eye

[37] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/droi/dv/138_abrahamfundstudy_/138_abrahamfundstudy_en.pdf

[38] https://scholar.google.co.za/scholar?q=Socioeconomic+Issues+affecting+bedouins&hl=en&as_sdt=0&as_vis=1&oi=scholart

[39] https://www.touristisrael.com/negev/295/

[40] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negev_Bedouin

[41] https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2022-11/internal-_resilience_series_-_bedouins_in_the_opt.pdf?ref=longroadmag.com#:~:text=Bedouins%20total%20approximately%2040%2C000%20people,the%201948%20Arab%2D%20Israeli%20War.

[42] https://escholarship.org/content/qt5fd390b0/qt5fd390b0.pdf

[43] https://www.jstor.org/stable/24585565

[44] https://www.newarab.com/news/settlers-hurl-stones-drivers-herders-west-bank

[45] https://www.newarab.com/news/settlers-hurl-stones-drivers-herders-west-bank

[46] https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2024/1/27/like-a-mafia-israeli-settlers-forces-squeeze-palestinian-shepherds-out

[47] https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2024/1/27/like-a-mafia-israeli-settlers-forces-squeeze-palestinian-shepherds-out

[48] https://www.routledge.com/Negev-Bedouin-and-Livestock-Rearing-Social-Economic-and-Political-Aspects/Abu-Rabia/p/book/9780367717032

[49] https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/roma-gypsies-in-prewar-europe

[50] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inuit

[51] https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/roma-gypsies-in-prewar-europe

[52] https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/genocide-of-european-roma-gypsies-1939-1945

[53] https://www.jstor.org/stable/3773568

[54] https://www.nature.com/articles/hdy201390

[55] https://cityterritoryarchitecture.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40410-016-0031-3

[56] https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/ethno-tourism-community-based-eco-tourism-market#:~:text=Ethno%2Dtourism%20is%20travel%20designed,tourists%20travel%20across%20the%20globe.

[57] http://www.stellenboschheritage.co.za/wp-content/uploads/Planning-and-Housing-in-the-Rapidly-Urbanising-World.pdf

[58] https://reliefweb.int/report/occupied-palestinian-territory/west-bank-israel-must-stop-demolition-palestinian-schools

[59] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0308518X16653404

[60] https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/11/12/genocide-in-gaza-a-call-for-urgent-global-action

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: Ethnic Cleansing, Gaza, Genocide, History, Human Rights, Indigenous Culture, Indigenous Rights, Israel, Jewish Settlers, Middle East, Palestine, Palestinian Rights, West Bank

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 12 Feb 2024.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: The Forgotten Bedouin Palestinian Herders, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

This beduins are probably decent from Nabatheans/Kenites. Roma Gypsies are descent from Melchizedekians which were Salemites/Rechabites. KENITES descent from Shasu-Shasas or Hindu RAKSHASAS and APIRU or Abhiru/Abhiras. Abhiras were Dravidians. Rakshasas were Aryans Brahmins. They were ancestors of KENITES. Jesus family were half Kenites half Rechabites . (check Simeon of Clopas Rechabite origin. Simeon was cousin to Jesus . Check Vatican archive. Salemites or Melchizedekians were members of Qumran community which was destroyed by Byzantine catholics. Jehonadab children mixed so much with Juda royals. Also with Aronites. Rechabites became Israelites because they mixed with Jews so much . They were ancestors of Roma Gypsies only. Different Gypsies are descent from different clans of KENITES.