Digitising Statelessness and Genocide in Palestine and Myanmar

PAPER OF THE WEEK, 11 Aug 2025

Natalie Brinham – TRANSCEND Media Service

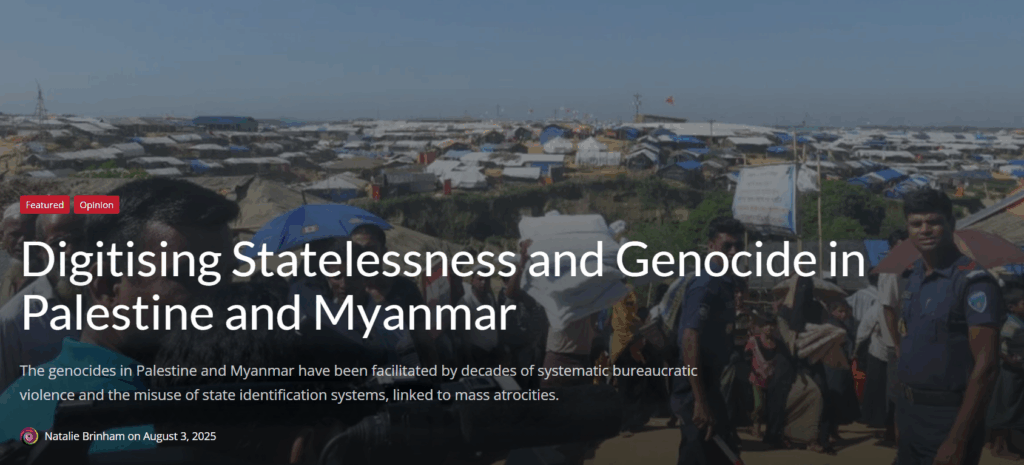

A scene of Rohingya refugee camps, one of the world’s largest population of genocide survivors, are crammed together in the hilly area in Cox’s Bazaar, Bangladesh, across the land border from Myanmar.

(Photo by Natalie Brinham, Nov 2017)

3 Aug 2025 – The genocides in Palestine and Myanmar have been facilitated by decades of systematic bureaucratic violence and the misuse of state identification systems. It’s high-time to rethink how state IDs and identification technologies are linked to mass atrocities. My new research brief is a small step towards this rethink. Here’s the thinking behind it.

The Historical Nexus between Statelessness and Genocide

A stateless person is someone who is not recognised as a citizen of any state. Historically, statelessness has been linked to genocide since before the terms were incorporated into international law. In 1944 Lemkin – in coining the term- described genocide as a dual process that aims to ‘destroy the national pattern of the oppressed group’ as well as ‘impose the national pattern of the oppressors’. In Lemkin’s conceptualisation, genocide was attempted through the systematic destruction of political and social institutions relating to culture, language, religion and economic existence of national groups. Citizenship, then was integral to genocide, but citizenship in a broader sense than an individual legal status. Hannah Arendt’s work The Origins of Totalitarianism in 1951 also linked mass denaturalisations and denationalisations in Europe during the interwar years to mass violence and extermination. She conceptualised the stateless person as someone who, without access to citizenship, was cast outside of the political community and was unable to realise their rights or access legal protections. It is Arendt’s conceptualisation of statelessness that tends to dominate today’s statist global discourses relating to ‘legal identities’ and ‘legal invisibility’. Within this conceptualisation, the passport or ID or work permit, acted as a mediator between the state authorities and the individual – it proved one’s belonging and provided access to a range of social, political, and economic rights, and promised safe passage and legal protections. Here, violence was understood as occurring as a result of the state denying their documents to individual humans, thus rendering them legally “invisible”.

Evolving Forms of ID Violence

In the interwar years, the technologies developed to link individual humans with the state records and classification systems were largely confined to photography, fingerprinting, and printing and production techniques that prevented “fakes” and “frauds”. Of course, just as technologies have evolved since then, so too have the techniques and strategies used by states to erase and destroy groups and persecute dissidents. The violence of state IDing systems and identification technologies is not confined to denying someone a document and thus delinking them from state and international legal protections. Systems that ID noncitizens (and those confined to lower tiers of citizenship) biometrically link humans through their body parts (not only documents) to a vast array of high-tech state infrastructure designed to surveille, control, expel, target, and sometimes kill. IDing systems are foundational to much of this infrastructure – from biometrics captured at internal borders, to motion and heat sensing, to CCTV, to open air prisons, to AI generated targets, and autonomous weapons. These forms of violence are closer to Lemkin’s original notion of genocide as the broad but systematic destruction of national groups, than to notions of ‘legal invisibility’.

IDing may have historically been linked to state crimes that target groups, but the proliferation of violent state technologies and violent state strategies, to which the IDing of noncitizens is linked, is unprecedented today. IDing has facilitated crimes against the group in both Myanmar and Palestine – from collective punishment, to apartheid, to mass deportations, to mass incarceration, to starvation as an weapon of war, to the acts of genocide including killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm: deliberately inflicting conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction; and imposing measures intended to prevent births.

The CCTV-dotted occupied Old City of Hebron is like a city in Nazi Germany with roads where native Palestinians are not allowed to walk. Like all of Palestinian territories under Israeli occupation, checkpoints and surveillance equipment are prevalent throughout this once holy city. In sharp contrast to its high-tech repression and control, the city has billboards transmitting biblical fairy tales-cum-messianic Zionist propaganda at different road intersections. This one reads, “The Jewish return to Hebron is historical justice”. Thousands of native Palestinians have been forcibly removed and their neighbourhoods taken over by settler families largely from USA armed with Made-in-USA M-16 combat machine guns and protected by several thousands Israeli Occupation Force, officially known as IDF) The Messianic Fascist Settler leader who now holds the National Security portfolio in the Far-right government, Ben Gvir, grew up here.

(Photo by Maung Zarni, January 2025)

“Interoperable” Infrastructures of Genocide?

So what? These ideas are mostly just “academic”. So, why does reconceptualising the links between genocide and noncitizenship matter?

Well, for one thing, many international actors still perceive the universal provision of state IDs to be a fundamentally good thing – to be used as a tool of social inclusion, as enshrined in Sustainable Development Goal 16.9 which aims for a “legal identity for all” by 2030. With all the impetus from UN agencies and multinational private tech firms working in the digital public infrastructure space, the SDG goal has become like an out of control juggernaut careering down the international development highway without any brakes, not noticing who or what it drives over. Evidence of today’s genocides should have slowed down that juggernaut down, and temper its enthusiasm for working with violent states. But it hasn’t. It will keep building speed, until the role of ID systems in state crimes is rethought.

For another thing, IDs, surveillance and bordering technologies are generally not viewed a weapon and so do not fall under arms embargos. As Israel commits genocide, it continues to export models of group oppression alongside genocide facilitating tech to oppressive regimes around the world including to Myanmar. Recategorizing exports based on broader understandings of state violence would be a start.

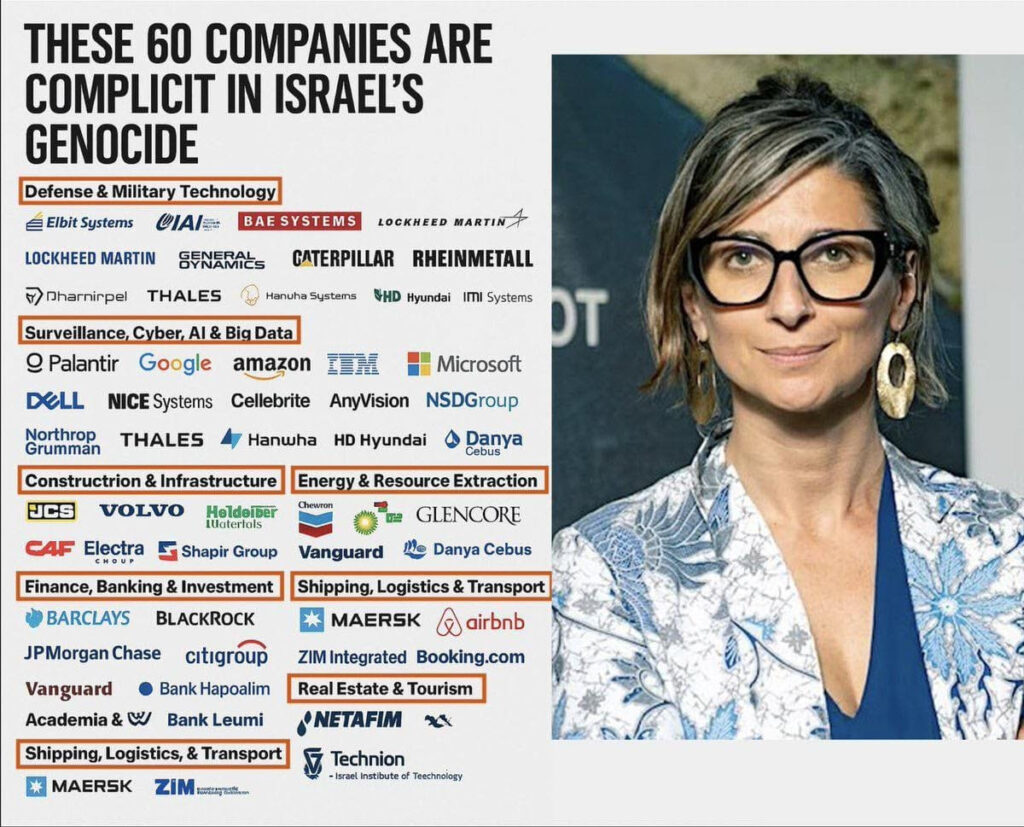

UN Special Rapporteur Francesca Albanese published a Report EXPOSING these 60 Companies Complicit in Aiding Israel. Facebook

And finally, with largely unaccountable multinational tech companies (for instance, the case of Palantir Technologies and Trump’s ICE) increasingly involved in, and profiting from, national ID systems world-wide, more robust protection frameworks are vital. Risk-assessments have continued to focus predominantly on privacy and data security by-passing the much more alarming use in mass citizenship violence and state xenophobia.

Thus far human rights assessment tools amount to little more than human-rights washing.

Added to this, the global push from tech experts and policymakers for “interoperability” and in digital ID systems and digital public infrastructure raises fresh concerns about the potential for their misuse in group persecution. For example, there are few safeguards against the misuse of information shared between state and refugee databases – even though this can result in the denial of protections and/or citizenship, or persecution in refugees’ home countries. Interoperability can make it easier to lock noncitizens out of life sustaining services, and far harder for them to go about their survival work in informal spaces. In short, there’s a risk that as the infrastructure of the state and welfare are made “interoperable”, the infrastructures of genocide also become “interoperable”.

Collectively reconceptualising the mechanisms of state violence that operate in the dark policy spaces between legal identities and bordering technologies, could be very productive. Analysis can be channelled towards fresh forms of action, activism, advocacy, new forms of genocide prevention, and ultimately solutions. Israel and Myanmar are committing genocides – but they are not committing the same genocides as the Nazis in the twentieth century. Contemporary genocides call for contemporary approaches.

My first small step is a three-page briefing paper and recommendations for the International Association of Genocide Scholars on “Statelessness and Genocide”.

A final thought

As a firm believer in the benefits of collaborative working and shared knowledge production, if you are interested in contributing to work or outputs relating to mainstreaming genocide sensitivity measure into ID systems or anti-statelessness work, please get in touch with me eq23321@bristol.ac.uk

______________________________________________

Natalie Brinham is Leverhulme Early Career Fellow (2024- ) and previously Economic and Social Research Council post-doctoral fellow (2023), both with the School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, the University of Bristol. and a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment. Under the pseudonym Alice Cowley, she co-authored a 3-year pioneering study of Myanmar’s slow-burning genocide of Rohingyas (2014). She has published extensively on the persecution of Rohingyas for academic publications and media outlets including Forced Migration Review, Project Syndicate. As a researcher and practitioner, Dr Brinham has been involved in both activism and scholarship on refugee affairs in Myanmar and UK over the last 20 years. She holds a PhD in legal studies from the Queen Mary University of London, an MA in education from the UCL Institute of Education and a BA (Hons.) in development and Thai Studies from SOAS University of London. natalie.brinham@gmail.com

Natalie Brinham is Leverhulme Early Career Fellow (2024- ) and previously Economic and Social Research Council post-doctoral fellow (2023), both with the School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, the University of Bristol. and a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment. Under the pseudonym Alice Cowley, she co-authored a 3-year pioneering study of Myanmar’s slow-burning genocide of Rohingyas (2014). She has published extensively on the persecution of Rohingyas for academic publications and media outlets including Forced Migration Review, Project Syndicate. As a researcher and practitioner, Dr Brinham has been involved in both activism and scholarship on refugee affairs in Myanmar and UK over the last 20 years. She holds a PhD in legal studies from the Queen Mary University of London, an MA in education from the UCL Institute of Education and a BA (Hons.) in development and Thai Studies from SOAS University of London. natalie.brinham@gmail.com

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER STAYS POSTED FOR 2 WEEKS BEFORE BEING ARCHIVED

Tags: Burma/Myanmar, Genocide, Israel, Palestine, Refugees, Research, Rohingya, Statelessness

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 11 Aug 2025.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Digitising Statelessness and Genocide in Palestine and Myanmar, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.