India-China Trade Route Warfare: Sandwiching Nepal

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 15 Sep 2025

Bishnu Pathak – TRANSCEND Media Service

Abstract

10 Sep 2025 – Nepal and India share many similarities in language, cuisine, traditional clothing, culture, customs, marriages, and festivals. The two countries allow visa-free travel with just an identity card. India has territorial disputes with all its neighboring countries. India and China have a long-standing rivalry, which raises security concerns for Nepal. India had 18 military check posts in Nepal’s high Himalayas along the border to monitor China but was disappointed withdrawing them. India has had military troops stationed in Nepal’s territories of Lipulek since 1962.

The objectives of the state-of-the-art paper are to examine the Nepo-India territorial disputes and analyze testimonies and other evidence that the Lipulek territories belong to Nepal. The information was gathered by drawing on experiences and archival literature reviews using the snowball technique from the past (yesterday), understanding the axiomatic truth of Lipulek territories in the present (today), and fostering hope for the transformation of disputes by dialogue for the future (tomorrow). A recent agreement between India and China to use a trade route passing through Nepal’s Lipulek territories has triggered protests in Nepal. The signing of the agreement by India’s National Security Advisor and China’s Foreign Minister, in the presence of the Indian Foreign Minister, has raised concerns about potential conspiracy theories aimed at pressuring Nepal.

Lipulek holds strategic significance as it is situated at the tri-junction of India, China, and Nepal. Residents of the Lipulek territory in the Darchula district of Nepal have several pieces of evidence to support their claim to the areas. These include land tax receipts, Nepali citizenship, voter lists, land ownership certificates, and participation in the Nepali population census. Historical maps dating back to the Sugauli Treaty of 1816 also show Lipulek as part of Nepal, with the Kali River serving as the eastern border. Additionally, the Joint Technical Level Nepal-India Boundary Committee (JTBC) was established in 1981 to reaffirm and maintain the border boundaries between the two countries. Over the past decade, Nepal has sent diplomatic notes to India on eight occasions but has not received any response. Anti-Indian sentiments are prevalent in Nepal due to India’s encroachment on lands and major rivers and the disrespectful, contemptuous, condescending, and ineffective behavior of Indian embassy employees in Kathmandu.

These employees are accused of fueling anti-Indian sentiments in Nepal, potentially influenced by China to safeguard their own positions. However, this perception holds little truth. India’s main weakness lies in its inability to cultivate harmonious relations with the people of Nepal, often prioritizing only infamous leaders in Nepal. Instead of resolving the territorial disputes, India’s Foreign Ministry always repeats the same old mantra, “The Lipulek territories claimed by Nepal belong to India.” Even though India has no choice but to engage in high-level bilateral meetings without hesitation, pursuing both indirect and direct mediation, as well as informal and formal dialogues. A man is great by soul, not by geography or population size or both. PM Modi has a great opportunity to be a leader of India alone or a great leader of all neighbors, transforming territorial disputes through peaceful means. Dialogue begets dialogue.

Introduction

Nepal’s Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli visited Tianjin on 30 Aug 2025 at the invitation of Chinese President Xi Jinping to attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) meeting between 31 Aug and 1 Sep. On the same day, an official meeting was held between the President of China and the head of government of Nepal, highlighting Nepal as a high priority.

During the meeting, Oli referenced the Sugauli Treaty of 1816, stating that all lands (Lipulek, Kalapani, and Limpiyadhura) 56 km east of the source of the Mahakali River belong to Nepal as a sovereign country. He expressed objection to the agreement between India and China, designating Lipulek, a Nepali territory, as a trade route during his discussion with Xi Jinping. In response, the Chinese president said, “The border dispute between Nepal and India is a matter for the two sides to resolve. Our agreement was not intended to weaken Nepal’s claim. Please understand” (Lamsal & Mishra, August 31, 2025). A press release from the Embassy of Nepal in Beijing reiterated Nepal’s objection to the recent understanding between India and China on the Lipulek Pass.

The Lipulek Pass is located on the Nepo-China border, an ancient route for merchants and pilgrims traveling between Nepal and Tibet, China. During the Sino-India war (October 20-November 21, 1962) (Hoffmann, 1990), Chinese military forces pushed Indian military forces up to the Lipulek Pass and then retreated.

The Sugauli Treaty of 1816 led to the loss of more than 50 percent of Nepal’s land to the British East India Company, shrinking Nepal’s territory from 267,000 sq. km to 147,000 sq. km. This loss included a crucial route to Tibet through Kumaon (Nepal News, January 27, 2025).

Indian media extensively covered PM Oli’s meeting regarding the Lipulek issue during his meeting with President Xi. They have portrayed Oli’s stance as nationalist, interpreting China’s lack of response as ‘strategic silence.’ Despite this, Chinese media has not acknowledged Nepal’s interest in Lipulek, which Nepal hopes to gain China’s support for. Nepal remains committed to the One China Policy, and China has expressed support for the Global Security Initiative (GSI). Ambitious-tactical Oli, in a 20-minute one-on-one meeting with the politico-ideologue and business strategist Xi, expressed support for the GSI, although Oli’s courtiers have refuted China’s claims.

Nepal is displeased with the agreement between India and China regarding the Lipulek territory, as it was done without informing and consulting Nepal. In November 2019, India added Nepal’s Lipulek region to its map, sparking a dispute. The issue dates back to 1962, when Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru sought permission from Nepal’s King Mahendra to station troops in Lipulek temporarily to counter China. However, this temporary arrangement became a permanent Indian occupation, leading to the ongoing border dispute with Nepal. The recent trade agreement between India and China in August 2025 has reignited the Lipulek Pass dispute, with Nepal strongly asserting its sovereignty over the area. The Lipulek Pass is a trijunction of Nepal, India, and China, with the historical context of Nehru’s agreement with King Mahendra adding complexity to the situation. This dispute underscores the strategic significance of Kalapani for India in the context of its border dynamics with China.

Nepal’s King Mahendra knew Indian forces were in Lipulek and remained silent, not choosing to contest India’s occupation for fear of appearing to side with China. Former foreign minister Bhek Bahadur Thapa confirmed King Mahendra’s awareness of Indian troops entering Kalapani during the war. Thapa wrote in his book that he decided to raise the issue after the war to seek a solution. Despite Indian troops withdrawing from Kalapani, they remained there, recognizing the strategic importance of the Lipulek Pass and established check-posts there. Besides, India has been increasing its presence and infrastructure in the area (Mishra, August 22, 2025).

India asserts Lipulek as its own, leading to a border dispute with Nepal. The Sugauli Treaty of 1816 designates that Lipulek, Kalapani, and Limpiyadhura territories belong to Nepal. During a meeting between Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping on August 31, 2025, Modi hinted that Lipulek would not be conceded to India. Modi emphasized the mutual benefits of the India-China relationship, benefiting 2.8 billion people and contributing to global well-being. President Xi underlined cooperation between the two countries, calling New Delhi a significant friend of Beijing and advocating for a strategic and long-term vision for their relationship.

Nepal is stuck between the elephant, India and the dragon, China. Whether two bulls graze peacefully in a farmer’s mustard field or engage in a fight, it is the farmer who suffers the loss. Nepal’s situation is akin to that of the farmer. If China and India cooperate harmoniously, Nepal will still be sandwiched in the middle. In the event of warfare, Nepal will bear the brunt of the suffering.

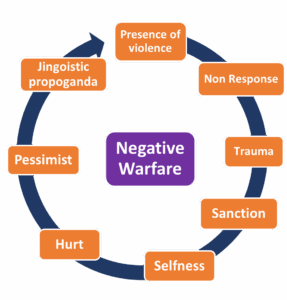

In this context, “warfare” refers to the intense pressure exerted by Nepal through eight diplomatic notes in ten years, protests in front of the India-China embassies in Kathmandu, political consensus, media campaigns, and civil societies towards both India and China to assert its claim. Warfare includes both positive and negative dimensions. Positive warfare is to use constructive methods to address and resolve conflicting issue applying both indirect and direct mediation as well as informal and formal dialogue, in order to reach a win-win or lose-lose conclusion. Negative warfare is turning a deaf ear to dissident voices, inviting human suffering-casualties through harmful consequences that can lead to lose-win or win-lose outcomes. Nepal strongly objects to India’s claim over the Lipulek Pass and surrounding areas, asserting its sovereignty and this dispute represents a new form of diplomatic warfare. Nepal is now expecting positive warfare from India and China regarding the Lipulek issue.

The study aims to investigate how Indian troops, initially seeking refuge from China, established a temporary settlement in the strategically vital area of Lipulek, which later evolved into a permanent base. It also delves into the decision-making process that led Indian leaders to not only retain control of Lipulek but also expand their presence to Kalapani and Limpiyadhura based on the army’s recommendations.

The general objective of the study is to comprehensively analyze the historical treaties, agreements, and protocols signed by Nepal and India, as well as their compliance trends. The specific objectives include investigating the current status of territorial disputes between Nepal and India, uncovering historical facts and evidence, gathering perspectives from various stakeholders such as commoners, civil society, intellectuals, and leaders of both countries.

This study provides descriptive and explanatory insights into the Lipulek, Kalapani, and Limpiyadhura areas. Information will be gathered through networking and tracking methods, drawing on the author’s previous works on “Negotiation by Peaceful Means: Nepo-India Territorial Disputes” (2022) and “Nepo-India Territorial Disputes Transformation by Dialogue Means” (2021) between Nepal and India.

This state-of-the-art paper utilizes experiences, media, and archival literature reviews to explore drawing on past (yesterday) conflicts between Nepal and India, the axiomatic truth approach of territorial dispute in the present (today), and fostering hope by sharing knowledge on present understanding to promote positive peace for the future (tomorrow). The work is based on personal experiences and observations accumulated over four decades, rather than relying solely on theoretical concepts.

Testimonies of Lipulek Belonging to Nepal

The Nepo-India dispute was triggered on November 2, 2019, when India’s Home Ministry issued a new official politico-administrative map changing the status of Jammu and Kashmir to a Union Territory. Additionally, the map included the Kalapani territories, causing uproar in Nepal (Dixit & Dhakal, May 19, 2020). The incorporation of Nepal’s Kalapani, Lipulek Pass, and Limpiyadhura areas in the map led to protests at all levels—central, provincial, and local—against India. Nepal requested Foreign Secretary-level talks by sending notes on November 20, 22, and December 30, 2019, but received no response from India (Mehta, June 26, 2020).

A tension over the map issue escalated; Nepal grew incensed when Defense Minister Rajnath Singh virtually inaugurated a link road connecting the border with China at the Lipulek Pass (Xavier, June 11, 2020). The construction of the road aimed to strengthen India’s defense supply lines and provide easier access for pilgrims to Kailash Mansarovar (Muni, May 22, 2020). Nepal claims that Kalapani, Limpiyadhura, and Lipulek Pass are territories of Nepal situated in the Darchula district (Giri, May 8, 2020, & Thapa, May 13, 2020). The trade route agreement between China and India in August 2025 via Lipulek has further heightened stiffnesses in Nepal.

The Kalapani territories has been a focus of Indian military posts. Nepal had overlooked military posts in the Kalapani area with from 1961 to 1997. In September 1998, a coalition government in Nepal reached an agreement with India on disputed border areas, including Kalapani. The agreement included resolving border disputes through mutual talks, discussing the 1950 Nepal-India security treaty, and preparing a report on the Mahakali Treaty and distribution of hydropower and water resources in border areas (Rose, 1999).

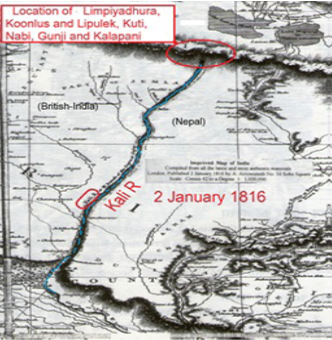

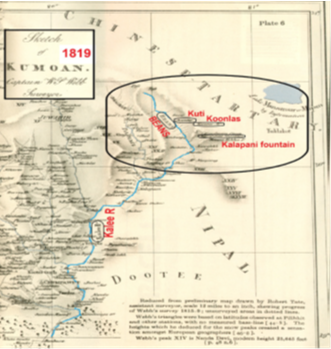

While the Anglo-Nepalese War (November 1, 1814-March 4, 1816) was ongoing, the Governor General of India sent a secret letter to the Secret Committee of the East India Company in London on June 1, 1815, stating that the Kali River should be the eastern boundary of East India with Nepal (Bhusal, March 2020). The secret letter stated, “The Kali forms a well-defined boundary from the snowy mountains to the plains, and though narrow, it is deep and rapid. The snowy range … touches the eastern confines of Kumaon. Hence, this is the shortest, and consequently the most defensible line of frontier” (Cox, 1824) (see Figure 1 & 2).

Nepal, with a porous border with India, shares a complex relationship involving diplomatic, socio-cultural, cartographic, economic, and political aspects due to their close proximity. India’s border disputes with all its neighboring countries, namely Pakistan to the west, China and Nepal to the north, Bhutan to the northeast, and Bangladesh and Myanmar to the east, have strained relations including Nepal. Reports suggest that India has breached border demarcations at 76 locations in Nepal. A recent agreement between India and China to trade through Nepal’s Lipulek territory has sparked protests in Nepal.

The agreement, signed by India’s National Security Advisor and China’s Foreign Minister in the presence of the Indian Foreign Minister on August 19, 2025, has raised concerns about potential conspiracy theories targeting Nepal and its politics. While the agreement explicitly mentions Pulan-Gunji reopening trading markets that pass through the Lipulek Pass. It is evident that PM Modi delegated the authority to sign the agreement to his much-trusted security advisor to exert influence and pressure on Nepal from a security point of view.

Figure 1 & 2: Map of Kali (Kalee) River, Limpiyadhura, Lipulek, Kuti, Nabi, Gunj, and Kalapani

FIGURE 1:

FIGURE 2:

| Figure 1: Kali River as the international border between British-India and Nepal (www.davidrumsey.com). | Figure 2: The uppermost reach of Kali River serves as the western border between British-India and Nepal (pahar.in/indian-subcontinent-pre-1899). |

| Note: The map was published by the East India Company when British India and Nepal signed the Sugauli Treaty on December 2, 1815. Figure 2 shows the pictorial clarification of the secret letter written by Lord Moira in 1815 (Cox, 1824).

Source: Evolution of cartographic aggression by India: A study of Limpiyadhura to Lipulek, March 2020. |

|

On one hand, India has given a clear message that the agreement was made at the behest of the army, while on the other hand, India seems to be trying to indirectly pressure Nepal if Nepal makes a lot of noise, India tries to send a clear message that the army would be deployed against Nepal’s dissident voices. This is a form of warfare diplomacy by the Indian political leadership, attempting to intimidate Nepal by promoting the security advisor. The absence of the Lipulek name in the document on China’s website further adds to the complexity and conspiracy of the situation.

The construction of roads, schools, bridges, police stations, and health posts in the villages of Budhi, Garbyang, Goonjee, Nabhee, Okutee, and Kuthee has brought comfort to the people. They now feel more connected to India than Nepal, but are equally saddened by the transition from Nepali to Indian citizenship. It only takes them a couple of days to reach New Delhi, while reaching Kathmandu takes much longer due to the difficulties of connecting roads in Nepal. Despite their Nepali mindset and heritage in terms of language, food, dress, culture, and relationships, they are drawn to the convenience provided by India.

It is important for the international community to understand why Nepal, a landlocked, least developed, and small country, is asserting that all lands east of the Kali River belong to Nepal, despite agreements between the world’s two major powers, India and China. It is crucial to grasp the rationale and testimonies behind Nepal’s claims.

The territory is situated in the Kalapani River basin, at elevations ranging from 3600 to 5200 meters. Lipulek is located at the top of the Kalapani valley, a historic trade route for the Bhotiyas of Tibet, Kumaon in India, and the Tinker valley of Nepal (Manzardo, Dahal & Rai, Undated). The Lipulek Pass is strategically significant as it offers a vantage point to monitor both China and Nepal. Despite Nepal’s claims since 1997 that Lipulek, Kalapani, and Limpiyadhura belong to Nepal, the Indian Army has maintained control of the territories. India has unofficially disregarded Nepal’s claims without formal discussions or testimonies and has not engaged in any dialogue on the issue.

Bhairab Risal, who led the Population Census in 1961, recorded details of each household in all settlements, including the villages of Kuti, Nabi, and Gunji located east of the Kali River (June 11, 2015). Old records of land ownership rights in Kuti, Nabi, and Gunji villages are available in the Land Administration Office, Doti district, which proves that Limpiyadhura belongs to Nepal (Bhusal, March 2020).

India and China both required Nepal’s approval to expand their border trade. On May 15, 2015, Sitaram Yechury, a leader of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), criticized the Joint Communiqué of China and India, arguing that both countries should have consulted Nepal before finalizing the trade route to Tibet and connectivity plan to Mansarovar (The Kathmandu Post, June 11, 2015). This sentiment was echoed by many leaders, intellectuals, and civil society members in India. India claims that the Lipulek Pass is at an altitude of 17,000 feet, with Mansarovar approximately 90 km away from Lipulek Pass (PTI, May 8, 2020 & PTI, May 8, 2020). By allowing vehicles to travel 5 km into China across Lipulek, the travel time has been reduced from 5 days to two days (Santhanam, August 12, 2019). The Indo-China Agreement of 1954 mentioned Lipulek for Indo-Tibetan trade (Nayak, June 9, 2015) and Kailash-Mansarovar pilgrimage traffic, which was reaffirmed in another trade agreement in 2015.

Both India and China needed to obtain Nepal’s consent to expand their border trade route. On May 15, 2015, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) leader Sitaram Yechury denounced the Joint Communiqué of China and India, stating that both countries should have consulted Nepal before deciding on the trade to Tibet and the connectivity plan to Mansarovar (The Kathmandu Post, June 11, 2015).

On February 4, 1817, Acting Chief Secretary John Adams of the East India Company sent an order letter to Commissioner G.W. Trail of Kumaon, instructing the surrender of the eastern side of the Kali River to the Government of Nepal. A copy of the letter was also sent to Edward Gardner, the Resident Commissioner of British India in Kathmandu. A month later, on March 2, 1817, John Adams directed G. W. Trail to acknowledge the receipt of all lands situated to the east of the Kali River for return. The borders between Nepal and India are demarcated based on Articles 3 and 5 of the Sugauli Treaty. Article 3 specifies the lowlands between the Rivers Kali and Rapti, between Rapti and Gunduck, between Gunduck and Coosah, between Mitchee and Teestah, and the territories within the hills eastward of the River Mitchee, including Nagree fort and Nagarcote Pass (Manandhar & Koirala, June 2001).

On March 8, 1817, the Kumaon Commissioner reported that villages east of the Kali River were to be attached to the Pergunnah of Dotee in Nepal. Apart from Tinkar and Changroo villages, six other villages – Boodhe, Gurbhuyan, Goonjee, Nabhee, Okutee, and Kuthee- were part of Nepal. The Zamindars lived on the west side of the Kali River in British India, while their tenants resided on the east side in Nepal. As a result, the Zamindars lost control of these six villages (Dhungel & Pun, August 2014).

The Sugauli Treaty, signed in the past, resulted in territorial concessions where many parts of Nepalese lands were ceded to British India. This treaty allowed Britain to recruit Nepalis, known as Gorkhas, for military service (www.timesnownews.com, July 31, 2020), a practice that continues in small numbers to this day. As a result of the treaty, Nepal lost over 50% of its territories, including regions like Darjeeling, Sikkim, west of Kali River like Kumaon, Garhwal (Uttarakhand), parts west of the Sutlej River (Himachal Pradesh), and various Tarai lowlands. Despite these territorial losses, cultural similarities such as shared meals, traditional attire, festivals, and customs related to death and marriage ceremonies can still be observed in these regions. Additionally, Nepali-speaking communities and ethnic groups from Nepal’s lost territories continue to exist.

The Sugauli Treaty, created by the East India Company without Nepal’s consent, did not include a map. Kalapani, Lipulek Pass, Nabi, Gunji, Kuti, and Limpiyadhura are all part of Nepali territory, supported by various facts, evidence, and testimonies. Historical boundary maps from 1819, 1827, 1850, 1856, 1879, and 1905 show that the Kali River serves as Nepal’s western border. The boundary extends from the Kali River originating at Limpiyadhura (Shrestha, June 27, 2015), as outlined in the Sugauli Treaty. The British Survey of India’s historic maps from 1827 and 1856 clearly depict the Kali River. India’s 1856 map (Budhathoki, November 11, 2019) shows the Mahakali River originating at Limpiyadhura. A map published by Arrowsmith in London on January 2, 1816, also shows the river originating from Limpiyadhura (Manandhar & Koirala, June 2001).

In the section on “The Kingdom of Nepal” in Walter Hamilton’s book “A Geographical, Statistical, and Historical Description of Hindustan, and the Adjacent Countries” (1971), it is mentioned that the Kali River is the western section of the Gogra River (Shah, November 13, 2019). Several maps published by the Survey of British India in various years from 1816 to 1856 also clearly show the origin of the Kali River to the west of the Gogra River (Mulyankan, September/October 1999).

A map from the Old Atlas of China (1903) published during the Qing Dynasty shows Limpiyadhura as the source of the Kali River (Shrestha, June 22, 2015) in Chinese characters. Scholar S.D. Muni noted that British maps from 1816 to 1860 favored Nepal’s position, but later maps supported India’s claim, possibly due to strategic interests. Muni suggested that India could lease Kalapanis from Nepal. However, he later aligned with India’s stance (Pathak & Bastola, 2023).

The Nepal-China Boundary Treaty of 1961 referenced Limpiyadhura and the Kali River. Article 1 stated, “The Chinese-Nepalese boundary line starts from the point where the watershed between the Kali River and the Tinkar River meets the watershed between the tributaries of the Mapchu (Karnali) River on the one hand and the Tinkar River on the other hand… passing through the Niumachisa (Limpiyadhura) …” (fall.fsulawrc.com/collection/LimitsinSeas/IBS050.pdf). “The Head of Mahakali is Limpiyadhura” (Naya Patrika, May 13, 2020).

The Kalapani issue garnered widespread attention from various segments of Nepalese society, including the general public, students, teachers, bureaucrats, professionals, civil society organizations, human rights activists, and political leaders. On June 26, 1996, a 39-member Public-level Border Encroachment Prevention Committee was established to investigate the facts surrounding the Kalapani territories. Led by veteran human rights activist Padma Ratna Tuladhar, the Committee included prominent figures from different fields[*]. They gathered extensive documentation and testimonies, such as tax records from villagers in Tinkar, Kunji, Bundi, Chhangru, and Nabi (Byas Gorkha areas) paid at the Land Revenue Office in Darchula until December 1978 (Mulyankan, September/October 1999).

Residents of the Nabi, Gunji, and Kuti villages in the Kalapani area used to pay land revenue (Bali) to the district authority of Darchula, Government of Nepal until 1978. Bhuwan Sharma notes that the government has records of land taxes paid by individuals from these villages and that they also obtained Nepali citizenship certificates (Sharma, May 30, 2020).

During the Panchayat era from 1960 to 1990, the understanding reached between King Mahendra (1955-1972) and India’s first PM Nehru, regarding the Limpiyadhura triangle was not known to the Nepali population. This period was marked by a closed administration, with government officials in the Darchula district reporting directly to the Narayanhiti Royal Palace, under the rule of both King Mahendra and his son King Birendra.

The two Kings remained silent indefinitely. Democratic leaders turned deaf ears having the establishment of Indian military posts in the Kalapani territories. Their silence persisted until the Mahakali Treaty (1995-1996) was ratified, causing the CPN (Marxist-Leninist) to split from its parent party CPN (UML) due to allegations of treason (Shrestha, June 16, 2020). The terms Kali river and Mahakali river refer to the same river, known as Mahakali in Nepal and Kali in India. The Kalapani issue was further exacerbated by the breakaway faction, sparking a contentious debate on the Mahakali Treaty (Kafle & Baral, June 16, 2020). Nepalis feel betrayed by the treaty, as the shared water resources have not been fair and equal distribution. The river has dried up while India has diverted all the water from the canal, leaving Nepal with water shortages in winter and floods in summer.

The Nepali people should not only blame India. If Nepali leaders had not favored India, India would not have gained control over major rivers for irrigation and hydropower in Nepal. Madan Bhandari, a proponent of people’s multi-party democracy, opposed the Mahakali Treaty and was mysteriously killed along with Jeevraj Ashrit. Amar Lama, the sole surviving witness to Bhandari’s murder, was also chased up to 2 km and killed on the orders of the then CPN (Maoist) Secretary General Badal. It has been revealed that the current PM Oli met with Badal before the murder and sought his help in the killing.

The author is willing to investigate the murders of Bhandari and Ashrit without any payment from the Government of Nepal. In order to be granted the authority to investigate, the author has already made a public vow in front of prominent Nepalese media. The truth for justice for the families of Bhandari and Ashrit will only be revealed once a thorough investigation into the murders is conducted, with a specific focus on the potential involvement of Prime Minister Oli. Many people are afraid to speak out against Oli for fear of retaliation or harm to their lives, but it is widely discussed unofficially among the Nepalese people that Oli is one of those implicated in Bhandari’s and Ashrit’s murder.

PM Oli, who played a principal role in getting the Mahakali treaty ratified by Parliament, received strong support from India. With active backing from India’s RAW, he rose to become the chairman of the CPN-UML. However, his short-sighted tactics did not last long. After assuming the presidency, he changed his stance, shifting from vehemently opposing India during the day but sought refuge in RAW at night. Now, having been rejected by both RAW and India, Oli is claiming that Ram was not born in India, but in Ayodhya in Thori, Nepal, without providing any evidence. He stated, “We believe that we gave ‘Sita’ to the Indian prince Ram. We gave the Ram of Ayodhya, not to India. Ayodhya is a village west of Birgunj, Nepal” (https://www.onlinekhabar.com/2020/07/881495). Currently, he is making every effort and promising everything in favor of China to maintain his power against India’s deception.

Indian military Controversy

On November 7, 1950, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, also known as the Iron Man of India and Deputy The Prime Minister and Home Minister wrote a letter to Prime Minister Nehru expressing concerns about India’s security in relation to China. In the letter, Patel emphasized the need for political and administrative measures to strengthen India’s northern and north-eastern frontier, including the borders with Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim, Darjeeling, and the tribal territory of Assam (www.friendsoftibet.org/sardarpatel.html). As a result, the Indian ambassador also urged Prime Minister Matrika Prasad Koirala to request the Indian Army’s assistance to secure Nepal and its newly established multiparty democracy from potential threats posed by China.

After Nepal declared itself a democratic country, breaking free from the 104-year rule of the Ranas, Matrika Prasad Koirala became the Prime Minister on November 16, 1951, replacing Mohan Shumsher JB Rana. Koirala visited New Delhi on January 6, 1952 where he requested PM Nehru’s assistance in reorganizing, training, and strengthening the Nepal Army (Pathak, September 15, 2014). Nehru accepted the proposal orally.

On February 27, 1952, 101 days after Nepal’s request, the Indian Army Mission (IAM) arrived in Kathmandu for a year. Later, the IAM was renamed the Indian Military Training and Adventure Group (IMTAG). In addition to training the Nepal Army, the IMTAG moved to strategic locations in the Northern Himalayas to monitor Tibet and China. They established 18 military posts along the Himalayan frontiers of Nepal, including Tinkar Pass in Darchula, Taklakot in Bajhang, Muchu in Humla, Mugugaon in Mugu, Chharkabhot in Dolpa Kaisang in Mustang, Thorang in Manang, Larkay Pass and Atharasaya Khola in Gorkha, Somdang and Rasuwagadhi in Rasuwa, Tatopani in Sindhupalchowk, Lambagar in Dolakha, Namche in Solukhumbu, Chepuwa Pass in Sankhuwasabha, Chyangthapu in Panchthar, and Olangchungola and Thechumbhu in Taplejung districts.

At each check-post, 20 to 40 Indian army officials armed with weapons and communication equipment were stationed, along with a few Nepali army and civilian officials (Shrestha, January 1, 2003). India increased its surveillance of various military groups at 18 check-posts due to concerns about the growing Chinese threat. Tensions between India and China escalated in March 1959 following the Tibetan uprising led by the Dalai Lama, who later sought refuge in India on March 30, 1959, with the assistance of the CIA (Whelpton, June 2016). Subsequently, the Dalai Lama established a Government in exile in Dharamshala, India (Jackson, February 29, 2009). The relationship between India and China has since remained contentious and competitive, impacting Nepal.

In his book “Border Management of Nepal” (January 1, 2003), Buddhi Narayan Shrestha mentioned that the Indian Military was sent back to India by the Government of Nepal on April 20, 1969. India was dissatisfied with this decision and threatened to close the border. However, India was eventually forced to withdraw all check-posts by August 1970. This marked the return of the Indian Army Mission after more than 18 years, staying an additional 17 years beyond the initially agreed-upon one-year period. Nepal did not object to the establishment of Indian troops in Kalapani (Darchula) in 1960, and India did not seek official permission from the Government of Nepal (Naya Patrika, May 20, 2020).

Conclusion

Nepal is in a complex situation where two influential nations, India and China, fluctuate between being adversaries and allies. These countries have contrasting ideologies—India operates under a competitive multi-party democracy with disorderly under-governed, while China follows a non-competitive people’s democracy with strict control and orderly over-governed. China’s economy is governed by proletarian politics, while India’s politics are influenced by economically affluent individuals.

The Indian system of governance is focused on business profits, dominating ideology, and security, while China is driven by political ambitions to dominate global trade, aiming to double its trade by day and quadruple it by night. The long-term trade relationship between India and China is unlikely to be positive warfare due to deep-seated mutual distrust. Indian people have a historical phobia of China, while Chinese people harbor anti-Indian sentiment. China’s commercial addiction and aggressive trade goals make it difficult for India to compete on an equal footing.

In this scenario, negative warfare is likely to arise between China and India. The current trade agreement between the two countries, which involves encroaching on Nepal’s Lipulek region, has been influenced by President Trump’s tariff policies. This situation is akin to a storm brewing. While Chinese goods will dominate the Indian market, the fragile relationship between China and India is bound to deteriorate. This imbalance means that Indian products will struggle to compete in China. Since the 1990s, there has been a vacuum in global political ideologies, with business interests taking precedence. Consequently, negative warfare is inevitable as business interests have replaced age-old traditional ideologies. In the 21st century, conflicts over resource control are likely to lead to negative warfare on a global scale.

Positive warfare and negative warfare are interconnected aspects of human society, much like two sides of a coin. They cannot be applied simultaneously. When one ends, the other emerges, similar to an ecosystem or the peace-conflict lifecycle. It is in the best interest of both countries to exercise patience and avoid encroaching on Nepal’s territory. Otherwise, Nepal could become a transit point for a third party, which could then act as a watchdog and encircle both nations, potentially posing a threat to their interests from Nepalese territory.

There is a proverb among Nepali elders that says, “If it rains, take shelter under a big tree, and if you are in trouble, follow a big person.” However, Nepal is experiencing more losses than gains from the trade warfare between giant neighbors, India and China. Nepal, like a shadow at the bottom of light, is caught between the superpower competition, hindering its development. Whether China and India cooperate or clash, Nepal is caught in the middle, under their control, being sandwiched, squeezed, and oppressed. The country struggles to become a true partner in development, progress, peace, and harmony as it seeks.

|

Summary of positive warfare and negative warfare |

|

|

Created by Professor Bishnu Pathak, PhD: September 2025 |

|

As individuals and families migrate from one place to another, Nepal remains stationary, facing challenges. However, there is hope for Nepal to progress and for its people to thrive. Additionally, the fluctuating moods and steep tariffs imposed by US President Trump on China and India may encourage industrialists from both countries to consider Nepal as a promising location to establish their factories and businesses. In Nepal, the US tariff is only 10 percent.

Nepal’s leaders must shoulder equal responsibility and accountability for the oppression, exploitation, stagnation, vulnerability, and helplessness experienced by the country. They lack comprehensive plans for national development and prosperity, instead prioritizing personal gain, family interests, sycophancy, and party politics. Their focus is on serving themselves rather than the well-being of the nation and its people.

During important high-level official meetings with neighboring countries like China and India, Nepal’s top leaders, including prime ministers and ministers, prioritize personal projects for their constituencies over national interests. This undermines their ability to assert Nepal’s territorial claims, such as addressing encroachments in Lipulek Pass. Past treaties, agreements, and actions suggest a history of prioritizing Indian interests, effectively acting as agents of India rather than champions of Nepal’s sovereignty. Hence, the future of such leaders is also at risk in Nepal.

During a pilgrimage to Mount Kailash and Mansarovar Lake, Nepalis are prohibited from entering the Kalapani area and the Lipulek Pass, which are part of their sovereign territory. The issues related to the Lipulek-Kalapani-Limpiyadhura areas have been neglected by Nepali authorities due to concerns about India’s power, politics, property, and privilege. The dispute in the Kalapani territories has been ongoing since India gained independence from British colonial rule and adopted Nehruvian socialism, but India has forgotten such socialism in practice.

China’s pursuit of unilateral benefits raises two pressing questions in Nepal: How long will China prioritize its own interests by signing a trade route warfare agreement with India through Nepal’s Lipulek without informing and cooperating with Nepal? And how long will Nepal continue to support the ‘One China Policy’ and the GSI? These questions have become deeply rooted in the minds of the Nepalese people, and China must address these concerns sooner rather than later. Despite Nepal’s frequent changes in government, the permanent force of resolution of its people remains steadfast. If China fails to provide a satisfactory answer to the Nepali people, both the ‘One-China Policy’ and Nepal’s alignment with the GSI are sure to be at great risk.

References:

1. Bhusal, Jagat K. (2020, March). “Evolution of cartographic aggression by India: A study of Limpiyadhura to Lipulek”. The Geographical Journal of Nepal. Volume 13.

- Budhathoki, Arun. (2019, November 11). “India’s Updated Political Map Sparks Controversy in Nepal”. The Diplomat. Washington DC: Diplomat Media Inc.

- Cowan, Sam. (2015, December 14). “The Indian check posts, Lipulek, and Kalapani”. The Record. Lalitpur.

4. Cox, J. L. (1824). Papers regarding the administration of the Marquis Hastings in India. London: India office Library.

- Dhungel, Dwarika N. & Shanta B. Pun. (2009). The India-Nepal Water Relationship Challenges. Kathmandu: Institute for Integrated Development Studies.

- Dhungel, Dwarika N. & Shanta B. Pun. (2014, August). “Nepal India Relations: Territorial Border Issue with Specific Reference to Mahakali River”. Foreign Policy Research Center. Volume 3. New Delhi.

- Dixit, Kanak Mani and Dhakal, Tika P. (2020 May 19). Territoriality amidst Covid-19: A premier to the Lipulek conflict between Indian and Nepal. Retrieved September 4, 2025, from https://kanakmanidixit.com/territoriality-amidst-covid-19-a-primer-to-the-lipu-lek-conflict-between-india-and-nepal/.

- Giri, Anil. (2020, May 10). “Nepal’s Statement on Lipulek welcome, but action should follow, analysts say”. The Kathmandu Post. Kathmandu: Kantipur Media Group.

9. Himal Press. (2025, September 3). China and India agree to resume through Lipulek. Retrieved September 3, 2025, from https://en.himalpress.com/india-china-agree-to-resume-trade-through-lipulek/.

- Hoffmann, Steven A. (1990). India and the China Crisis. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press.

- International Boundary Study. (1965, May 30). Retrieved June 19, 2020, from https://fall.fsulawrc.com/collection/LimitsinSeas/IBS050.pdf.

- Jackson, Peter. (2009, February 29). “Witness: Reporting on the Dalai Lama’s escape to India”. Reuters.

- Kafle, Parsuram and Baral, Janardan. (2020, June 16). “Nepali Rastriyatamathiko Auta Dukhanta: Sadakma Janatamathi Lathicharge, Samsadma Mahakalimathi Mahaghata (A Tragedy for Nepalis: Baton Charges to the People on the Streets, Great Shocking on Mahakali in the Parliament)”. Naya Patrika. Kathmandu: New Publication.

14. Lamsal, Laxmi and Mistra, Rajesh. (2025, August 31). “Chiniya Rastrapati Xi Sangha Pradhan Mantri Olile Uthaye Lipulekko Muddha (PM Oli raises Lipulek issue with Chinese President Xi)”. Kantipur. Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://epaper.ekantipur.com/kantipur/2025-08-31.

- Manandhar, Mangal Siddhi and Koirala, Hriday Lal. (2001, June). “Nepal-India Boundary: River Kali as International Boundary”. Tribhuvan University Journal. Volume XXIII, No. 1.

16. Manzardo, Andrew E., Dahal Dilli R. and Rai, Nabin Kumar. (Undated). The byanshi: an ethnographic note on a trading group in far western Nepal. INAS Journal. Retrieved June 25, 2022, from himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/contributions/pdf/INAS_03_02_06.pdf.

- Mehta, Ashok K. (2025, June 26). “Why the border issue with Nepal flared up”. The Tribune. Chandigarh.

- Mishra, Rajesh. (2025, August 22). “A six-point primer on past and present of Lipulek controversy”. The Kathmandu Post. Retrieved August 31, 2025, from https://kathmandupost.com/national/2025/08/22/a-six-point-primer-on-past-and-present-of-lipulekh-controversy.

- (1999, September/October). Kasari Bhayekochha Kalapanima Sima Atikraman (How the border is encroached in Kalapani). Year 17, No. 70.

- Muni, SD. (2020, May 22). “Lipulek: The past, present, and future of the Nepal-India stand-off Analysis”. The Hindustan Times. New Delhi.

- Naya Patrika. (2020, May 20). “Indian Army on Nepali Soil: 18 posts for 18 years”. Kathmandu: New Publication.

- Nayak, Nihar R. (2015, June 9). Controversy over Lipulekh Pass: Is Nepal’s Stance Politically Motivated? New Delhi: Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis.

23. Nepal News. (2025, January 27). Full Text of the 1816 Sugauli Treaty: The Agreement That Cost Nepal Two-Thirds of Its Land. Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://english.nepalnews.com/s/history-culture/full-text-of-the-1816-sugauli-treaty-the-agreement-that-cost-nepal-two-thirds-of-its-land/.

- Parashar, Sachin. (May 19, 2020). “Boundary issue on bilateral agenda for two decades: Nepal”. The Times of India. New Delhi.

- Pathak, Bishnu and Bastola, Susmita. (2023c). “Eastern Philosophy”. TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved September 6, 2025, from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2023/05/eastern-philosophy/.

- Pathak, Bishnu. (2014, September 15). “India’s PM Modi towards World’s Top Leader Keeping Confidence with Neighbours”. TRANSCEND Media Service.

- Prakash, Anirudh. (2020, May 22). “K Gujral’s misplaced altruism has led to Kalapani dispute”. The Hills Times. Guwahati.

- (2020, July 14). “PM Oli says “real” Ayodhya is in Nepal and Lord Ram is Nepali; BJP rejects claim”. The Hindu. New Delhi.

- (2020, June 15). “’Serious diplomatic lapse’: Karan Singh slams government over Indo-Nepal border row”. The New Indian Express. New Delhi.

- (2020, May 8). “Rajnath Singh inaugurates strategically crucial road in Uttarakhand”. The Times of India. New Delhi.

- Regmi, Avantika. (2019, November 29). Lipulekako Rananitik Mahatwa (The Strategic Importance of Lipulek). Kathmandu: Khabarhub.com.

- Rose, Leo E. (1999). Nepal and Bhutan 1988: Two Himalayan Kingdoms. The Regents of the University of California.

- Santhanam, Radhika. (2019, August 12). “In Manasarovar, Chinese lend a helping hand to Indian pilgrims”. The Times of India. New Delhi.

- Sardar Patel’s Letter to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. (1950, November 7). Retrieved May 22, 2025 from friendsoftibet.org/sardarpatel.html.

- Shah, Dipta Prakash. (November 13, 2019). “Nepal: Sugauli Treaty-1816 & Breach of Recognized State Obligation”. Telegraphnepal. Kathmandu.

- Sharma, Bhuwan. (2020, May 30). “Residents of Nabhi, Gunji, and Kuti used to pay land revenue to Nepal until 2035 BS”. myRepublica. Kathmandu: Nepal Republic Media.

- Shrestha, Buddhi Narayan. (2003, January 1). Border Management of Nepal. Kathmandu: Bhumichitra Co.

- Shrestha, Buddhi Narayan. (2015, June 22). “Yam indeed”. The Kathmandu Post. Kathmandu: Kantipur Media Group.

- Shrestha, Buddhi Narayan. (2015, June 27). Authenticity of Lipulek border pass. Nepal Foreign Affairs.

- Shrestha, Hriranya Lal. (2020, June 16). “Matribhumiko Aastha Ra Antaraatmako Aawaj Sunera Whip Ullanghan Garyou (We violated the party’s whipby listening to the voices of the motherland’s faith and inner soul)”. Naya Patrika. Kathmandu: New Publication.

- Thapa, Gaurab S. (2020, May 13). “Nepal confronts India in Lipulek border dispute”. Asian Times.

- The Kathmandu Post. (2015, June 11). “Indian Communist leader Yechury denounces India-China statement”. Kathmandu: Kantipur Media Group.

- Tuladhar, Padma Ratna, et al. (1999, September/October). A Report Prepared by Pubic-level Border Encroachment Prevention Committee, Nepal. Kathmandu.

- Whelpton, John. (2016, June). A History of Nepal. Cambridge University Press.

45. www.timesnownews.com. (2025, July 31). Gurkha recruitment legacy of past, says Nepal; calls 1947 tripartite agreement ‘redundant’. Retrieved September 3, 2025, from https://www.timesnownews.com/india/article/gurkha-recruitment-legacy-of-past-says-nepal-calls-1947-tripartite-agreement-redundant/630297.

- Xavier, Constantino. (2020, June 11). Interpreting the India-Nepal border dispute. Retrieved June 7, 2025, from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/06/11/interpreting-the-india-nepal-border-dispute/.

NOTE:

[*] (1) Prof. Chaitanya Misra, (2) Bhairab Risal, (3) Prof. Om Gurung, (4) Prof. Kapil Shrestha, (5) Prof. Krishna Bhattachan, (6) Prem Bahadur Bhandari, (7) Prof. Surendra K.C., (8) Dr. Bidor Osti, (9) Dr. Baburam Bhattarai, (10) Prof. Mangal Siddhi Manandhar, (11) Chandreswar Shrestha, (12) Sindhu Nath Pyakurel, (13) Chandra Raj Dhungel, (14) Maheswarman Shrestha, (15) Shyam Shrestha, (16) Pramesh Hamal, (17) Shanta Shrestha, (18) Dr. Sarad Onta, (19) Dr. Ram Man Shrestha, (20) Prof. Rajesh Gautam, (21) Ninu Chapagai, (22) Shyam Krishna Koji, (23) Buddhi Narayan Shrestha, (24) Ramesh Sharma, (25) Narayan Krishna Nhunchhe Pradhan, (26) Dr. Saroj Dhital, (27) Prof. Kalyan Dev Bhattarai, (28) Dr. Narayan Pokhrel, (29) Suresh Ale Magar, (30) Prof. Govinda Bhatta, (31) Prem Krishna Pathak, (32) Chaitanya Sharma, (33) Krishna Ram Khatri, (34) Khagendra Sangroulla, (35) Rameshwarman Amatya, (36) Jiwan Sharma, (37) Chatendra Jung Rimal, and (38) Manik Lal Shrestha (Mulyankan, September/October 1999).

_______________________________________________

Prof. Bishnu Pathak was a former Senior Commissioner at the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons (CIEDP), Nepal who has been a Noble Peace prize nominee 2013-2019 for his noble finding of Peace-Conflict Lifecycle similar to the ecosystem. A Board Member of the TRANSCEND Peace University holds a Ph.D. in interdisciplinary Conflict Transformation and Human Rights in two decades. Arduous Dr. Pathak who is an author of over 100 international paper-book publications has been used as references in more than 100 countries across the globe. Immense versatile personality Dr. Pathak’s publications belong to Human Rights, Human Security, Peace, Conflict Transformation, and Transitional Justices among others. He can be reached at ciedpnp@gmail.com.

Prof. Bishnu Pathak was a former Senior Commissioner at the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons (CIEDP), Nepal who has been a Noble Peace prize nominee 2013-2019 for his noble finding of Peace-Conflict Lifecycle similar to the ecosystem. A Board Member of the TRANSCEND Peace University holds a Ph.D. in interdisciplinary Conflict Transformation and Human Rights in two decades. Arduous Dr. Pathak who is an author of over 100 international paper-book publications has been used as references in more than 100 countries across the globe. Immense versatile personality Dr. Pathak’s publications belong to Human Rights, Human Security, Peace, Conflict Transformation, and Transitional Justices among others. He can be reached at ciedpnp@gmail.com.

Tags: Asia, British Colonialism, British empire, China, Conflict, Himalayas, India, Nepal

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 15 Sep 2025.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: India-China Trade Route Warfare: Sandwiching Nepal, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

One Response to “India-China Trade Route Warfare: Sandwiching Nepal”

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.

Dear Prof.Bishnu Pathak

PAST and FUTURE suggested a way of the OPTIMIST PROJECT- and role of PEACE-OPERATOR in a ERA of AI

I have just send you and other friends news about CHINA-WORLD PEACE FOUNDATION a new place in Beijing where 178 countries signed agreement for Peace-included NEPAL

called FESTIVAL of PEACE is a- 12° ANNIVERSARY relaised in BEIJING GARDNER MUSEUM of PEACE

contact online with UNESCO were 100 million-last 19 September

now we are need OPTIMIST IDEA to WORK together-I remembered you that in CHINA in the past I met only GALTURG-the same in ROME-VATICANO in 2018 a NEW PEACE JOURNALISM born

by- POPE FRANCIS-IDEA to reformed comunication

I was delegated by China XINHUA AGENCY

now dialogue included WIN to WIN

the same opportunity to ALL-EDUCATION in the WORLD

best wishes

Rosa Dalmiglio