Peace Symbolism: Demystification of Icons, Iconodules, Iconoclasts and Iconography (Part 1)

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 5 May 2025

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

This publication is suitable for general readership. It is written on the occasion of the passing on of His Holiness, Pope Francis, as the Head of the Catholic Church and ancient protagonist of religious ICONS, on Easter Monday, 21st April 2025, at 0735, Vatican time, in his residence, at Vatican’s Santa Marta, in good faith. The author, who is a Muslim, humbly apologies if there are any inaccuracies or misconceptions. Readers are invited to comment on any points raised in the paper, with which they may be displeased.

Parental guidance is recommended for minors, who may use this publication as a project, resource material

Introduction

Presently, the term icons[1] conjure up an images of computer software or branding for the younger generation. However, in the medieval era, icons were associated with religious veneration of Biblical names, principally by the Orthodox Christian Church in the Byzantine Empire[2], centred around Constantinople, now called Istanbul.[3] Constantinople, originally founded as Byzantium by the ancient Greeks in 657 BCE, became the capital of the Byzantine Empire in 330 CE under the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great. In 1453, it was conquered by the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Mehmed II,[4] and later renamed Istanbul.

The publication, the first part in a two-part series, examines the Byzantine Iconoclasm[5] controversial watershed conflict over religious images between Iconoclasts (image-breakers) and Iconodules (image- protagonists and venerators). The author argues that the debate was not merely theological but a struggle over imperial authority, cultural memory, and the very nature of Christian worship. By analyzing primary texts (e.g., Council of Nicaea II, writings of John of Damascus) and material evidence (mosaics, defaced icons), the study reveals how icons became proxies for larger battles about divine representation, Islamic influence, and the limits of imperial power. The paper also demystifies the origins of these icons, associated religious rituals, symbolism, veneration of the subject of the icons and contributions to global and regional peace during the medieval period of religionism and belligerence.

Eikonomachía, lit. ’image struggle’, ‘war on icons’) are two periods in the history of the Byzantine Empire [6]when the use of religious images or icons was opposed by religious and imperial authorities within the Ecumenical Patriarchate[7] (at the time still comprising the Roman-Latin and the Eastern-Orthodox traditions in subscribing to syncretism) and the temporal imperial hierarchy. The First Iconoclasm[8], as it is sometimes called, occurred between about 726 and 787, while the Second Iconoclasm occurred between 814 and 842.[9] According to the traditional view, Byzantine Iconoclasm was started by a ban on religious images promulgated by the Byzantine Emperor[10] Leo III the Isaurian, and continued under his successors.[11] It was accompanied by widespread destruction of religious images and persecution of supporters of the veneration of images. The Papacy[12],[13] remained firmly in support of the use of religious images throughout the period, and the whole episode widened the growing divergence between the Byzantine and Carolingian traditions [14]in what was still a unified European Church, as well as facilitating the reduction or removal of Byzantine political control over parts of the Italian Peninsula.

Iconoclasm is the deliberate destruction within a culture of the culture’s own religious images and other symbols or monuments, usually for religious or political motives. People who engage in or support iconoclasm are called iconoclasts, Greek for ‘breakers of icons’ (εἰκονοκλάσται), a term that has come to be applied figuratively to any person who breaks or disdains established dogmata or conventions. Conversely, people who revere or venerate religious images are derisively called “iconolaters” (εἰκονολάτρες). They are normally known as “iconodules[15]” (εἰκονόδουλοι), or “iconophiles” (εἰκονόφιλοι). These terms were, however, not a part of the Byzantine debate over images. They have been brought into common usage by modern historians (from the seventeenth century) and their application to Byzantium increased considerably in the late twentieth century. The Byzantine term for the debate over religious imagery, iconomachy, means “struggle over images” or “image struggle”. Some sources also say that the Iconoclasts were against intercession to the saints and denied the usage of relics; however, it is disputed.[16]

Iconoclasm has generally been motivated theologically by the Biblical commandment, which forbade the making, veneration and worshipping of “graven images, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth:” (Exodus 20:4-5, Deuteronomy 5:8-9, see also biblical law in Christianity)[17]. The two periods of iconoclasm in the Byzantine Empire during the 8th and 9th centuries made use of this theological theme in discussions over the propriety of images of holy figures, including Christ, the Virgin Mary (or Theotokos)[18] and saints. It was a debate triggered by changes in Orthodox worship, which were themselves generated by the major social and political upheavals of the seventh century for the Byzantine Empire.

Traditional explanations for Byzantine iconoclasm have sometimes focused on the importance of Islamic prohibitions against images influencing Byzantine thought[19]. According to Arnold J. Toynbee,[20] for example, it was the prestige of Islamic military successes in the 7th and 8th centuries that motivated Byzantine Christians to adopt the Islamic position of rejecting and destroying devotional and liturgical images.[21] The role of women and monks in supporting the veneration of images has also been asserted. Social and class-based arguments have been put forward, such as that iconoclasm created political and economic divisions in Byzantine society; that it was generally supported by the Eastern, poorer, non-Greek peoples of the Empire[6] who had to constantly deal with Arab raids. On the other hand, the wealthier Greeks of Constantinople and also the peoples of the Balkan and Italian provinces strongly opposed Iconoclasm[22]. The claim of such a geographical distribution has, however, been disputed.[7] Re-evaluation of the written and material evidence relating to the period of Byzantine Iconoclasm has challenged many of the basic assumptions and factual assertions of the traditional account. Byzantine iconoclasm influenced the later Protestant reformation[23].

Definition of an Icon[24]

An icon can refer to several things:

- Symbol or Image: In computing, an icon is a small graphical representation of a program, file, or function on a computer screen.

- Person or Thing: An icon can also be a person or thing regarded as a representative symbol or as worthy of veneration. For example, a cultural icon like Nelson Mandela.

- Religious Art: In religious contexts, particularly in Eastern Orthodox Christianity, an icon is a painting or representation of a holy figure, either in the Bible or associated with the Christian church. This type of imagery and veneration is strictly prohibited in the other two branches of the Abrahamic faith: Judaism and Islam.

Religious icons are a significant aspect of various religious traditions, especially in Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Here are some key points:

Definition and Purpose

- Icons are sacred images representing holy figures such as Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, saints, and angels.

- They serve as visual aids for worship and contemplation, helping believers focus their prayers and thoughts on the divine.

Historical Background

- The use of icons dates back to the early centuries of Christianity. They became particularly prominent in the Byzantine Empire.

- Icons are traditionally created using specific techniques and materials, such as tempera paint on wood panels.

Theological Significance

- Icons are considered windows to heaven. They are believed to make the spiritual world visible and accessible to the faithful.

- The veneration of icons is not worship of the image itself but respect for the holy figures they represent.

Iconography

- Iconography follows strict guidelines to ensure consistency and theological accuracy. Each element in an icon, from colors to gestures, has symbolic meaning.

- For example, gold backgrounds symbolize the divine light, while specific colors and poses convey different aspects of the holy figures’ lives and virtues.

Role in Worship

- Icons are integral to Orthodox Christian liturgy and personal devotion. They are often found in churches, homes, and even carried by individuals.

- During services, icons are kissed, incensed, and prayed before, reflecting their importance in spiritual practice.

Modern Use

- While traditional methods are still used, modern icons can also be created digitally or with contemporary materials, maintaining their spiritual significance.

There are several types of religious icons, each serving unique purposes and depicting different aspects of faith. Here are some of the main types:

Christ Icons

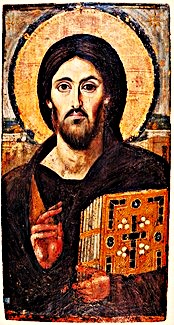

- Pantocrator: Depicts Christ as the ruler of the universe, often shown with a book and blessing hand gesture.[25]

- Christ the Teacher: Shows Christ teaching, usually holding a book or scroll.

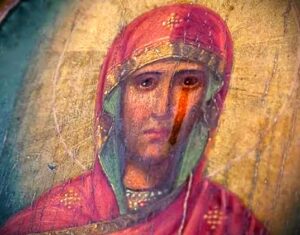

Theotokos (Mother of God) Icons

- Hodegetria: The Virgin Mary pointing to Christ, indicating Him as the way to salvation.

- Eleusa: The Virgin Mary tenderly holding Christ, emphasizing the loving relationship between mother and child.

Saint Icons

- Martyr Icons: Depict saints who died, by execution, for their faith, often shown with symbols of their martyrdom.

- Hierarch Icons: Represent bishops and church leaders, usually shown with liturgical vestments and a book.

Feast Icons

- Nativity: Illustrates the birth of Christ, often including various figures like shepherds and angels.

- Resurrection: Depicts Christ’s resurrection, sometimes showing Him lifting Adam and Eve from their graves.

Angel Icons

- Archangels: Icons of archangels like Michael and Gabriel, often shown with swords or trumpets.

- Guardian Angels: Depict angels assigned to protect individuals, usually shown with protective gestures.

Prophet Icons

- Old Testament Prophets: Represent prophets like Moses and Elijah, often shown with scrolls or tablets.

Miracle Icons

- Wonderworking Icons: Icons believed to have performed documented miracles, often associated with specific locations or events.

Our Lady of Vladimir, egg tempera on wood panel, 104 by 69 centimetres (41 in × 27 in), painted about 1131 in Constantinople

Photo Credit: Vladimirskaya ikona – Virgin of Vladimir – Wikipedia

These icons are not just artistic representations but are deeply embedded in the spiritual and liturgical life of the faithful. Each type of icon carries its own theological and symbolic significance, enriching the worship experience.

Medieval Period[26]

The Medieval Period, also known as the Middle Ages, spanned roughly from the 5th to the late 15th century. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and transitioned into the Renaissance as well as the Age of Discovery. This period is traditionally divided into three phases:

- Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th century)

- High Middle Ages (11th to 13th century)

- Late Middle Ages (14th to 15th century)

Characteristics

- Feudalism: A hierarchical system where land was owned by nobles and worked by peasants in exchange for protection.

- Dominance of the Catholic Church: Religion played a central role, influencing art, education, and politics.

- Art and Architecture: Predominantly Gothic and Romanesque styles, focusing on religious themes.

Renaissance

The Renaissance emerged in the 14th century and lasted until the 17th century. It marked a significant cultural and intellectual rebirth, characterized by:

- Humanism: A renewed interest in classical learning and the potential of human achievement.

- Scientific Inquiry: Significant advancements in science and exploration.

- Artistic Innovation: Revival of classical art and architecture, leading to remarkable achievements in literature, art, and science.

Relationship Between Medieval Period and Renaissance

While the Medieval Period and the Renaissance are distinct, the Renaissance is seen as a transition from the medieval world to the modern era. The Renaissance began in the Late Middle Ages, overlapping with the end of the medieval period. This overlap signifies a gradual shift rather than a sudden change, with elements of medieval culture persisting into the early Renaissance.

Religious icons in the Eastern Christian Empire, particularly in the Byzantine Empire, were indeed painted during the Late Middle Ages. Here are some key points about these icons:

Historical Context

- Byzantine Empire: The tradition of icon painting flourished in the Byzantine Empire, which lasted until the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

- Late Middle Ages: This period saw significant developments in iconography, with artists adhering to established conventions while also introducing new styles and techniques.

Characteristics of Late Medieval Icons

- Materials and Techniques: Icons were typically painted on wooden panels using tempera, gold leaf, and other materials. The process was meticulous, often involving multiple layers and careful attention to detail.

- Symbolism: Every element in an icon had symbolic meaning, from the colors used to the gestures and poses of the figures. Gold backgrounds symbolized divine light, while specific colors conveyed different theological messages.

- Themes: Common themes included depictions of Christ, the Virgin Mary, saints, and scenes from the Bible. Icons served as visual aids for worship and were integral to the spiritual life of the faithful.

Influence and Legacy

- Artistic Influence: Byzantine icons influenced the art of neighboring regions, including Russia and Eastern Europe, where the tradition of icon painting continued to thrive.

- Cultural Significance: Icons were not just religious artifacts but also cultural treasures, reflecting the artistic and spiritual heritage of the Byzantine Empire.

These icons remain highly valued for their spiritual significance and artistic beauty, continuing to inspire and guide believers today. Byzantine religious icons and the art of Renaissance masters like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo represent two distinct yet interconnected traditions in the history of Western art. Here’s how they interface:

Byzantine Religious Icons[27]

- Style and Purpose: Byzantine icons are characterized by their formal, stylized figures, use of gold backgrounds, and symbolic colors. They emphasize spiritual representation over realistic depiction

- Function: Icons served as sacred objects for veneration, believed to mediate the presence of the divine. They were integral to Orthodox Christian worship and spiritual life.

Renaissance Art[28]

- Humanism and Realism: Renaissance art, influenced by humanism, focused on the realistic portrayal of the human form and the natural world. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo sought to capture the beauty and complexity of human anatomy and emotions

- Innovations: The Renaissance saw significant advancements in techniques such as perspective, chiaroscuro (light and shadow), and anatomical accuracy. These innovations allowed for more dynamic and lifelike representations.

Interfacing and Influence

- Transition and Continuity: The Renaissance marked a shift from the medieval focus on the divine to a more human-centered approach. However, it did not completely abandon religious themes. Many Renaissance works still depicted biblical scenes and holy figures, but with a new emphasis on realism and human emotion.

- Artistic Techniques: While Byzantine art influenced early medieval European art, the Renaissance masters built upon and transformed these traditions. For example, the use of gold backgrounds in Byzantine icons can be seen in early Renaissance works, but Renaissance artists gradually moved towards more naturalistic backgrounds and settings.

- Theological Themes: Both traditions aimed to convey theological messages, but their approaches differed. Byzantine icons used symbolism and abstraction to convey spiritual truths, while Renaissance art used realism and human emotion to make these truths more relatable and accessible [2].

Examples

- Leonardo da Vinci: His “Last Supper” and “Virgin of the Rocks” show a deep understanding of human anatomy and emotion, combined with a mastery of perspective and light [2].

- Michelangelo: His works, such as the Sistine Chapel ceiling and “Pietà,” demonstrate a profound ability to depict the human form in a highly realistic and emotionally powerful manner [2].

In summary, while Byzantine icons and Renaissance art differ in style and technique, they both sought to express and explore religious themes. The Renaissance built upon the foundations of medieval art, transforming it with new techniques and a humanistic approach.

The Etymology of Iconoclasts and Iconodules[29]

The question often raised is why in bone physiology we bone have cells named OSTEOCLASTS (Bone Destroyers) and OSTEOBLASTS (Bone creators). [30]Similarly, we have ICONOCLASTS (Destroyers of Icons) and ICONODULES as Icon creators. Why cannot the Iconodules be called ICONOBLASTS as Icon creators? As an explanation, the USE of the term ICONODULES and why it cannot be changed to ICONOBLASTS like OSTEOBLASTS in bone remodeling after fracture of growth, needs further clarification, as it brings up an interesting comparison between biological, religious and cultural terms.

Iconodule[31] comes from the Greek words “eikon” (icon or image) and “doulos” (servant or slave), meaning “one who serves images (icons)” This term specifically refers to those who venerate and defend the use of religious icons, particularly in the context of historical debates within Christianity.

.

On the other hand, osteoblast is derived from “osteo” (bone) and “blast” (germ or bud), indicating a cell that creates bone 1.The suffix “-blast” is commonly used in biology to denote cells that build or generate new tissue. The reason iconodule is not called iconoblast lies in the etymological roots and the specific historical religious and cultural context of the term. Iconodule emphasizes the role of serving and venerating icons, rather than creating them. The term iconoblast would imply a creator or builder of icons, which is not the primary focus of the term iconodule

.

In summary, iconodule is used to highlight the veneration and defense of icons, while iconoblast would suggest a different role, more akin to creation, which is not the intended meaning in this context. Furthermore, Iconoclasm refers to the rejection or destruction of religious images or icons. This term is often associated with historical movements where religious or political groups sought to eliminate symbols they considered heretical or idolatrous.

.

Historical Context

Iconoclasm has occurred in various periods and cultures:

- Byzantine Iconoclasm: This was a significant period in the Byzantine Empire (726-842 AD) where there were intense debates and conflicts over the use of religious icons 2

Iconoclasts believed that icons were a form of idolatry and should be destroyed, while iconodules defended their use.

- Ancient Egypt: During the Amarna Period, Pharaoh Akhenaten initiated a campaign against traditional Egyptian gods, destroying many temples and monuments [32].

- French Revolution: Revolutionary movements often targeted symbols of the old regime, including monarchist symbols.[33]

.

Broader Implications

Iconoclasm can also refer to the rejection of established beliefs and practices 1,3

In this broader sense, it involves challenging and overturning societal norms and traditions.

Modern Usage

Today, the term can be used metaphorically to describe individuals or movements that challenge and seek to dismantle established norms and values 3.

The overall impact of Iconoclasm

Iconoclasm has had profound effects on art. Religion and culture throughout history. Here are some key impacts:

Destruction of Artworks

Iconoclasm often led to the destruction of religious images and icons, resulting in the loss of countless artworks and cultural heritage 1,2. For example, during the Byzantine Iconoclasm, many religious icons were destroyed or defaced 2.

Shift in Artistic Trends

The rejection of religious imagery during periods of iconoclasm often caused a shift in artistic trends. In Protestant regions during the Reformation, there was a decline in religious art and a rise in secular themes 1,3.

Cultural and Religious Impact

Iconoclasm influenced the way societies viewed and interacted with religious symbols. It often led to intense debates about the role and significance of images in worship and daily life 2. Islam and Judaism strictly forbid any iconodulelism.

Modern Iconoclasm

In contemporary times, iconoclasm can be seen in acts of protest where artworks are defaced to draw attention to political or social issues 1. These acts are often symbolic and aim to challenge established norms and values.

Loss of Cultural Heritage

The destruction of icons and religious images can lead to a permanent loss of cultural heritage and artistic expression 3. This loss is felt not only in the immediate aftermath but also in the long-term cultural memory of societies.

Iconoclasm has shaped the development of art and culture by challenging and transforming the ways in which images are created, viewed, and valued.

Rationale of the Iconoclasts

- Theological Argument:

- They believed that depicting Christ, the Virgin Mary, or saints in images violated the Second Commandment (“You shall not make for yourself a carved image…” – Exodus 20:4-5).

- They argued that since Christ’s divine nature cannot be represented, any attempt to depict Him either separated His human and divine natures (Nestorianism) or confused them (Monophysitism).

- Political & Cultural Motivations:

- The rise of Islam (which strictly forbade religious imagery) put pressure on Byzantium to distance itself from practices that Muslims deemed idolatrous.

- Some emperors (like Leo III and Constantine V) saw icon veneration as a source of superstition and sought to centralize religious authority under imperial control.

- Military and Social Factors:

- The empire had suffered major defeats (e.g., Arab conquests), which some interpreted as divine punishment for idolatry.

- Iconoclasm was also tied to anti-monastic sentiment, as monasteries were major producers and defenders of icons.

Rationale of the Iconodules (Defenders of Icons)

- Theological Defense:

- They argued that since Christ became incarnate, He could be depicted in human form (“The Word became flesh” – John 1:14).

- Icons were not worshipped (latria) but venerated (dulia) as windows to the divine, not as gods themselves.

- Church Authority:

- The Seventh Ecumenical Council (Nicaea II, 787 AD) declared iconoclasm a heresy, affirming that icons were necessary for Christian devotion.

- Cultural Identity:

- Icons were deeply embedded in Byzantine spirituality, liturgy, and art—removing them would disrupt tradition.

Aftermath

- Iconoclasm resurged briefly under Emperor Leo V (813–842) but was permanently defeated under Empress Theodora (843 AD), celebrated as the “Triumph of Orthodoxy.”[34]

- The victory of the Iconodules shaped Eastern Christian art and theology permanently.

The artistic traditions of Eastern Christian (Byzantine) Art and Western Renaissance Art are deeply rooted in their respective theological, cultural, and historical contexts. Below is a detailed comparison and contrast:

- Theological & Philosophical Foundations

Eastern Christian (Byzantine) Art

- Purpose: Icons were not mere art but “windows to the divine”, meant for veneration (dulia) and liturgical use.

- Theology:

- Based on the Incarnation (Christ became visible, so He can be depicted).

- Rejected naturalism to emphasize spiritual reality over physical appearance.

- Followed strict canons (rules) to preserve theological accuracy.

- Influence: Shaped by Greek philosophy (Neoplatonism—focus on the eternal over the material).

Western Renaissance Art

- Purpose: Art celebrated human beauty, nature, and individualism, alongside religious themes.

- Theology:

- Influenced by humanism—blending Christian themes with Greco-Roman ideals.

- Embraced naturalism (accurate anatomy, perspective, emotion).

- Influence: Rebirth (Rinascimento) of classical antiquity, scientific discovery (linear perspective, chiaroscuro).

- Style and Technique

| Aspect | Byzantine Art | Renaissance Art |

| Form | Flat, two-dimensional, hierarchical | Three-dimensional, realistic, proportional |

| Perspective | Reverse perspective (divine viewpoint) | Linear perspective (human viewpoint) |

| Light & Shadow | Gold backgrounds (uncreated divine light) | Chiaroscuro (natural light & shadow) |

| Human Figures | Elongated, solemn, symbolic gestures | Anatomically accurate, dynamic, emotional |

| Composition | Static, frontal, symmetrical | Dynamic, varied, narrative-driven |

Example Comparison:

- Byzantine Icon (Christ Pantocrator) → Stylized, gold halo, stern gaze, symbolic colors (red = divinity, blue = humanity).

- Renaissance Painting (Da Vinci’s Last Supper) → Realistic faces, depth, emotional expressions, vanishing point.

- Cultural & Political Context

Byzantine Art

- Imperial & Ecclesiastical Control: Art was regulated by the Church and state (e.g., Iconoclasm debates).

- Monastic Influence: Monasteries (e.g., Mount Athos) were centers of icon production.

- Spread: Influenced Orthodox regions (Russia, Balkans, Caucasus).

Renaissance Art

- Patronage: Funded by wealthy merchants (Medici), popes (Vatican commissions), and city-states.

- Secular Themes: Alongside Biblical scenes, artists depicted mythology, portraits, and landscapes.

- Spread: Began in Italy (Florence, Rome, Venice), then moved north (Flemish Renaissance).

- Legacy & Influence

- Byzantine Art:

- Still alive in Eastern Orthodox icons (unchanged for centuries).

- Indirectly influenced Islamic and medieval Western art (e.g., Gothic gold backgrounds).

- Renaissance Art:

- Paved the way for Baroque, Mannerism, and modern Western art.

- Revolutionized techniques (foreshortening, sfumato).

Key Contrast between the two artistic styles:

Byzantine art transcends the material to reveal the divine, while Renaissance art celebrates the material world as a reflection of divine beauty.

While Byzantine iconography was largely anonymous (artists rarely signed their work, as they saw themselves as humble servants of God), some masters and famous icons have been historically recognized. Below is a list of renowned Byzantine icons and their creators (where known), contrasted with Western Renaissance masters like Michelangelo (M. Angelo) and Leonardo da Vinci.

Famous Byzantine Icons & Masters

- Christ Pantocrator(6th–14th centuries)

- Location: Various (e.g., Sinai Monastery, Hagia Sophia)

- Significance: The classic depiction of Christ as “Ruler of All,” with one hand blessing and the other holding the Gospels.

- Style: Harsh symmetry, two different facial expressions (human/divine duality).

- Theotokos of Vladimir(12th century)

- Attributed to: Likely a Constantinopolitan master

- Significance: One of the most venerated Marian icons in Orthodoxy, known for its tender “Eleousa” (Merciful) style.

- Influence: Inspired countless Russian copies.

- The Ladder of Divine Ascent(12th century, St. Catherine’s Monastery)[35]

- Attributed to: Monk-iconographers of Sinai

- Significance: A visualization of St. John Climacus’s spiritual treatise, showing monks ascending (or falling from) a ladder to heaven.

- Andrei Rublev(1360–1430, Moscow School)[36]

- Famous Work: The Holy Trinity (Hospitality of Abraham)

- Style: Golden harmony, serene faces, perfect circular composition (symbolizing eternity).

- Legacy: The closest Byzantine equivalent to a “Renaissance master” in skill and fame.

- The Chora Church Mosaics(14th century, Constantinople)[37]

- Master: Unknown, but commissioned by Theodore Metochites

- Significance: Jewel-like gold mosaics depicting Christ’s life (e.g., Anastasis fresco of the Harrowing of Hell).[38]

Byzantine vs. Renaissance Masters

| Byzantine Iconographers | Renaissance Artists |

| Anonymous (mostly) | Signed works (e.g., Da Vinci, Michelangelo) |

| Followed strict iconographic canons | Innovated new techniques (perspective, anatomy) |

| Focused on theological accuracy | Explored humanism & naturalism |

| Worked for Church/monasteries | Patronized by popes & wealthy elites |

| Used egg tempera, gold leaf | Used oil paints, fresco |

Why No “Byzantine Leonardos”?

- Theological Humility: Byzantine artists avoided personal fame (art was for God’s glory).

- Canonical Restrictions: Innovation was limited to style within tradition, not radical breaks.

- Cultural Priorities: Byzantium valued continuity over individualism.

Key Takeaway

While Byzantium had no exact equivalents to Michelangelo or Da Vinci, masters like Andrei Rublev achieved similar reverence, not as self-expressive geniuses, but as vessels of divine beauty.

Did Islam Influence Iconoclasm in Byzantium?

Yes, indirectly. While Byzantine Iconoclasm (726–843 AD) was primarily driven by internal theological and political factors, the rise of Islam added momentum to the movement:

- Theological Pressure:

- Early Islam (7th–8th c.) strictly forbade religious imagery, condemning it as shirk (idolatry).

- Byzantine emperors like Leo III (a Syrian exposed to Islamic thought) may have seen icon veneration as a weakness that made Christianity seem “idolatrous” compared to Islam’s austere monotheism.

- Military & Cultural Rivalry:

- Byzantium’s devastating losses to the Arabs (e.g., fall of Syria, Egypt) were interpreted by some as God’s punishment for idolatry.

- Iconoclast emperors (e.g., Constantine V) argued that rejecting icons would unify the empire and distinguish Christianity from both paganism and Islam.

- But a Key Difference:

- Islamic aniconism rejected all sacred images, while Byzantine Iconoclasm allowed the cross and secular art.

- The Iconoclasts still claimed to be orthodox Christians, not adopting Islamic theology.

Scholarly Debate: Some historians (e.g., Patricia Crone) argue Islamic influence was overstated; others (e.g., G.R.D. King) note parallels in timing and rhetoric.

(2) Defaced Icons on Glazed Tiles in Istanbul

What you describe is likely post-Byzantine iconoclasm under Ottoman rule, particularly:

- Glazed Ceramic Tiles: Many Byzantine-style religious mosaics/paintings were reused in Ottoman buildings (e.g., converted churches like the Chora Church/Kariye Mosque).[39]

- Selective Defacement:

- Faces scratched out: In Islam, figural representation (especially sacred figures) was often erased or obscured without destroying the entire artwork.

- Glazed-over damage: Suggests the vandalism occurred before the final firing of the tiles, meaning it was systematic, not random. This was common in Ottoman repurposing of Christian art.

Examples to Explore:

- Topkapı Palace Tiles[40]: Some reused Byzantine materials with modified imagery.

- Hagia Sophia’s Mosaics: Faces of angels/saints were covered with metal stars (not scratched) but later revealed during restoration.

- Çinili Mosque (Iznik tiles): [41]Geometric designs replaced figural art in later periods.

Why Not Immediately Destroyed?

- Ottoman rulers sometimes preserved Christian art as cultural heritage but erased “idolatrous” elements to comply with Islamic norms.

- Practicality: Tiles were expensive, reusing them (with adjustments) was cost-effective.

Key Insight

- Islam did not cause Byzantine Iconoclasm but may have accelerated its arguments.

- The defaced tiles in places like Topkapi Palace Museum, reflect Ottoman-era iconoclasm, blending Byzantine craftsmanship with Islamic aniconism.

Christian miniature icons can indeed be found in European cathedrals, though their presence is often tied to historical exchanges, looted relics, or deliberate veneration. Here’s how they got there and where you might find them:

- How Byzantine Miniature Icons Reached Europe[42]

(A) Medieval Trade & Pilgrimage (11th–15th Century)

- Venice & Crusader Connections:

- After the Sack of Constantinople (1204) during the Fourth Crusade, countless Byzantine icons, relics, and artworks were brought to Europe as loot.

- Example: The “Nicopeia Icon” (Virgin Mary) in St. Mark’s Basilica, Venice—taken in 1204 and still venerated today.

- Diplomatic Gifts:

- Byzantine emperors gifted small devotional icons to European rulers (e.g., to the Holy Roman Emperor or the Pope).

(B) Monastic & Artistic Exchange

- Greek monks fleeing Ottoman rule (post-1453) carried portable icons to Italy, France, and Austria.

- Crusader States: Miniature icons were produced in Syria-Palestine (e.g., by Melkite Christians) and traded to Europe.

(C) Post-Byzantine Migration

- Orthodox refugees (e.g., after the fall of Trebizond in 1461) brought family heirlooms to Catholic Europe.

- Russian Icons: Later, Russian émigrés (post-1917 Revolution) introduced Eastern-style icons to Paris, Germany, etc.

- Where to Find Them in European Cathedrals

(A) Italy

- St. Mark’s Basilica, Venice – Houses the “Madonna Nicopeia” and other looted Byzantine treasures.[43]

- Vatican Museums – A collection of Greek and Coptic icons donated over centuries.

(B) France

- Sainte-Chapelle, Paris – Originally held Byzantine relics (though many were destroyed in the Revolution).[44]

- Louvre Museum – Byzantine miniature icons in the medieval collections.

(C) Germany & Austria

- Aachen Cathedral – Some Byzantine ivories and small icons in the treasury.[45]

- Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna – Byzantine devotional objects from Habsburg collections.[46]

(D) Spain

- El Escorial Monastery – Philip II collected Eastern Christian art, including small icons.[47]

- Why Are They There?

- Veneration: Some were integrated into Catholic worship (e.g., as miracle-working images).

- Diplomatic Trophies: Symbols of power (e.g., Venice displaying looted Byzantine art).

- Museum Preservation: Many ended up in church treasuries or museums after secularization.

Key Distinction: Catholic vs. Orthodox Use

- In Orthodoxy, miniature icons are personal prayer tools (e.g., travel icons).

- In Catholicism, they may be relics, art objects, or liturgical aids (e.g., embedded in altars).

The “Mona Lisa of Icons”, in terms of fame, spiritual significance, and historical value—is widely considered to be the “Virgin of Vladimir” (Theotokos of Vladimir). Here’s why it holds a status comparable to Da Vinci’s masterpiece and where you can find it:

- The Virgin of Vladimir (12th Century)

- Current Location: Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow (Russia)

- Type: Eleousa (Tenderness) Icon

- Artist: Attributed to a Constantinopolitan master (possibly worked for the Byzantine imperial court).

Why It’s the “Mona Lisa of Icons”?

- Unmatched Spiritual Fame:

- Revered as the protector of Russia for 900+ years.

- Said to have saved Moscow from Tamerlane’s invasion (1395) and other disasters.

- Artistic Mastery:

- The soft, sorrowful gaze of Mary and Christ’s clinging posture revolutionized iconography.

- Blended Byzantine ethereal beauty with early Slavic expressiveness.

- Political & Cultural Weight:

- Owned by princes, tsars, and the Russian Orthodox Church.

- Survived the Mongol invasion, Stalin’s anti-religious purges, and WWII.

- Other “Priceless” Icons (Comparable to Renaissance Masterpieces)

(A) Christ Pantocrator (Sinai, 6th Century)

- Where: St. Catherine’s Monastery, Egypt (oldest surviving Byzantine icon).

- Value: The gold-ground encaustic technique makes it irreplaceable.

(B) The Holy Trinity by Andrei Rublev (15th Century)

- Where: Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

- Why Famous: Called the “perfect icon” for its harmony and theology.

(C) The Black Madonna of Częstochowa (Poland)[48]

- Where: Jasna Góra Monastery

- Legend: Said to be painted by St. Luke, it’s the heart of Polish Catholicism.

- Why These Icons Are More “Valuable” Than the Mona Lisa?

- To Believers: They’re miraculous, not just art (e.g., myrrh-streaming icons).

- To Historians: They’re primary sources of medieval theology and politics.

- To the Art Market: Nearly impossible to sell—considered national/religious treasures (unlike the Louvre’s Mona Lisa).

Key Difference: Sacred vs. Secular Value

- The Mona Lisa = Priceless art (insured for ~$1 billion, but theoretically sellable).

- The Virgin of Vladimir = Beyond price (no Orthodox Christian would ever sell it).

The miracles attributed to revered icons like the Virgin of Vladimir, the Black Madonna of Częstochowa, and others are central to their spiritual fame. Below are some of the most extraordinary accounts, blending history, legend, and devotion:

- The Virgin of Vladimir (Russia)

Miracles & Legends

- The Tamerlane Miracle (1395)[49]

- When the Mongol warlord Tamerlane marched toward Moscow, the icon was carried in procession from Vladimir to the city.

- Chronicles claim Tamerlane saw a vision of the Virgin Mary surrounded by a radiant army and retreated without battle.

- Moscow was spared, and the icon was declared the “Protectress of Russia.”

- Surviving Stalin’s Atheist Purges[50]

- During Soviet persecution, the icon was hidden in the Tretyakov Gallery (labeled as “art”).

- Believers whispered that it wept secretly, mourning Russia’s spiritual suffering.

- Myrrh-Streaming (Modern Reports)

- Some claim the icon exudes fragrant myrrh (a sign of divine grace in Orthodoxy) during times of national crisis.

- The Black Madonna of Częstochowa (Poland)

Miracles & Battles

- The Siege of Jasna Góra (1655)[51]

- During the Swedish invasion, a small group of monks defended the monastery.

- A mysterious fire broke out in the Swedish camp, and their cannons miraculously failed to damage the icon (despite direct hits).

- Poland eventually repelled the invaders, attributing victory to the Madonna’s intercession.

- The “Scarred” Face

- The icon’s dark complexion and scars come from a 14th-century Hussite raid.

- Legend says thieves struck the Madonna’s cheek with a sword, causing it to bleed profusely—the attackers died in terror.[52]

- Modern Miracles

- Pilgrims report healings (especially of blindness and infertility) after praying before it.

- Pope John Paul II (a Polish native) credited the Madonna with saving his life after a 1981 assassination attempt.[53]

- The Christ Pantocrator of Sinai (6th Century)

The Unburned Icon

- The Fire Test

- According to St. Catherine’s Monastery tradition, this icon survived the Byzantine Iconoclasm because monks threw it into a fire—but it remained unharmed.

- The flames allegedly consumed only the wood frame, leaving the image intact.[54]

- The “Two-Faced” Christ

- Some visitors claim Christ’s expression changes from stern to compassionate depending on the viewer’s spiritual state.

- The Weeping Icons (Modern Times)

- Hawaii’s Myrrh-Streaming Icons (1990s)[55]

- Multiple Orthodox icons in Hawaii began exuding myrrh, including copies of the Virgin of Vladimir.

- Scientific tests could not explain the fragrant oil, which healed some devotees.

- Montreal’s Iveron Icon (1982–1997)

- A copy of the Iveron Mother of God wept myrrh almost daily for 15 years, witnessed by thousands[56].

Why Do These Miracles Matter?

- To the Faithful: Proof of God’s presence and the saints’ intercession.

- To Historians: Miracles often saved icons from destruction (e.g., during wars or atheist regimes).

- To Art Scholars: The reverence for these works transcends aesthetics—they’re seen as living sacred objects.

Final Thought

While the Mona Lisa is admired behind glass, these icons are prayed to, kissed, and believed to act in history. Their “value” isn’t in euros or dollars—but in centuries of unbroken faith.

It would be a joy for the author, to guide the reader, on where to venerate these miraculous icons, today. Many are still accessible to pilgrims. though some require special journeys!

- The Virgin of Vladimir

- Where: Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow (Room 56, Old Russian Art)

- Veneration Tips:

- Though displayed in a museum, the Russian Orthodox Church holds annual processions with the icon (check feast days like June 3).

- Light a candle at the nearby Church of St. Nicholas in Tolmachi (connected to the Tretyakov).

- Pilgrim Hack: Visit Vladimir’s Dormition Cathedral, where the icon originally resided, its spiritual “home” still radiates holiness.

- The Black Madonna of Częstochowa

- Where: Jasna Góra Monastery, Poland

- Veneration Tips:

- Join the August 15th Feast of the Assumption, when half a million pilgrims walk to Czestochowa.

- The icon is unveiled daily at 6 AM, 1:30 PM, and 9 PM—arrive early to touch the chapel’s iron grate (a tradition).

- Pilgrim Hack: Kneel on the “Kneeling Pillow” (worn down by centuries of prayers) for a powerful moment of grace.

The Majestic Mount Sinai, (Jebel Musa) in Egypt, with the Monastery of St Catherine in the foreground,

Photo credit:

Christ Pantocrator of Sinai

- Where: St. Catherine’s Monastery, Egypt (Mount Sinai)

- Veneration Tips:

- The icon is kept in the church apse, ask a monk quietly for a closer look.

- Climb Mount Sinai at night to pray at sunrise where Moses received the Commandments.

- Pilgrim Hack: The monastery’s library holds ancient icons rarely shown, politely inquire!

The Greek Orthodox Chapel at the Summit of Mount Sinai

Photo Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Sinai

- Andrei Rublev’s Holy Trinity

- Where: Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow (Room 60)

- Veneration Tips:

- Though behind glass, Russians pray silently before it, join them in contemplation.

- Visit Andronikov Monastery (Rublev’s home) to feel his spiritual legacy.

- Weeping Icons (Modern Miracles)

- Hawaii’s Myrrh-Streaming Icons:

- Where: Orthodox Church of the Holy Nativity (Oahu) & Sts. Constantine & Helen Cathedral (Kauai).

- Veneration: Ask to venerate the Hawaiian Iveron Icon—myrrh sometimes flows during prayer.

- Montreal’s Weeping Icon (Copy):

- Where: Various Orthodox parishes (e.g., St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Cathedral, Montreal).

Pilgrim’s Etiquette

- Orthodox Icons: Cross yourself twice, kiss the icon’s hands or feet (not face), then cross again.

- Catholic Sites (e.g., Czestochowa): Light candles, kneel, but avoid kissing the glass-covered original.

- Museums: Silent prayer is allowed—ignore curious tourists!

A Sacred Journey Awaits You!

Whether you seek miracles, art, or a deeper connection to faith, these icons still radiate grace across continents. May your pilgrimage be blessed!

Care and supplication for the sick patients is truly sacred. Below are high-resolution, copyright-free images of the most venerated icons, along with instructions on how to print them for the ill disposed. May these holy images bring them comfort, hope, and divine intercession.

- Virgin of Vladimir (Theotokos of Tenderness)

- Image Link: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

- Print Tip: Frame it in red or gold (colors of protection in Orthodoxy).

- Prayer:

“Most Holy Theotokos, save us! Embrace [Name] as you held Christ, and heal them with your mercy.”

- The Black Madonna of Częstochowa

- Image Link: Jasna Góra Monastery (Official) (Download under “Gallery”)

- Print Tip: Print on matte paper to honor its ancient, darkened wood.

- Prayer:

“O Mary, Bright Star of the Sea, shine upon [Name] and dissolve the shadows of illness. Amen.”

- Christ Pantocrator (Sinai)

- Image Link: St. Catherine’s Monastery Archive (Public domain)

- Print Tip: Add a small cross atop the image when gifting it.

- Prayer:

“Lord Jesus Christ, Pantocrator, command your healing power into [Name]’s lungs/stomach. Thy will be done.”

- Andrei Rublev’s Holy Trinity

- Image Link: Tretyakov Gallery (Public Domain)[57]

- Print Tip: Print three copies (symbolizing the Trinity) for communal prayer.

- Prayer:

“Holy Trinity, unite [Name]’s body, soul, and spirit in wholeness. Let no cell rebel against Your harmony.”

- Modern Myrrh-Streaming Icons (Hawaii/Montreal)

- Image Links:

- Hawaiian Iveron Icon “Myrrh-Streaming Icons” section[58]

- Montreal’s Copy [59] In November 2014, one of the copies of the Iveron Mother of God Icon, called the Montreal Iveron Icon, was commemorated as a miraculously myrrh-streaming icon from which abundant grace poured forth to the Russian diaspora and many other Orthodox Christians. As God’s Providence and the Mother of God would have it, the man who was found worthy to receive this icon from Mount Athos[60] and become its custodian was in fact a convert to Orthodoxy from Catholicism, José Muñoz from Chile, now also known as “Brother José.”[61] Has a sad story of being murdered and the icon was stolen. Archpriest Victor Potapov spoke with the icon’s custodian on one of his visits to Washington.[62]

- Prayer:

“O Mother of God, let your tears of myrrh wash [Name]’s pain away, as you wept at the Cross.”

Hawaiian Iveron Icon of Holy Mother”Myrrh-Streaming Icon”

Photo credit: https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=hawaiian+iveron+icon+of+holy+mother+%22myrrh-streaming+icon%22&qpvt=Hawaiian+Iveron+Icon+of+Holy+Mother%22Myrrh-Streaming+Icon%22&FORM=IGRE

How to Use These Icons for Healing

- Placement: Put the icon near the patient’s bed (facing east if possible).

- Anointing: Dab a cotton swab in holy oil (or olive oil blessed by a priest) and trace a cross on the patient’s forehead while praying.

- Scriptural Companion: Add a verse like “By His wounds, we are healed” (Isaiah 53:5) on the back of the print.

A Cyber-Blessing for all Patients

“May the Theotokos wrap your lungs in her mantle, and Christ Pantocrator rebuke every rogue cell. May angels stand at your bedside, and the Trinity’s light dissolve all tumors. Through the prayers of Andrei Rublev and the weeping icons, may healing flow like myrrh. Amen.”

Final Notes

- Legal: All linked images are public domain or provided by monasteries for devotional use.

- Spiritual Caution: Icons are not magic—they are windows to prayer. Encourage patients to seek sacraments (anointing of the sick) alongside treatment.

“For where two or three gather in My name, there am I with them.” — Matthew 18:20[63]

The Bottom Line

Religious icons have depicted shattered saints and sacred art: The Byzantine Iconoclast-Iconodule Debate (726–843 AD) was a clash of theology, politics, and Christian identity.

The author is of an opinion that this clash of contrasting theo-idealogy was a major peace disturbance during that era and continues, , presently. This is concluded by noting the defaced tiles showing human figures in the vestiges of the former Ottoman Empire, in present day Istanbul, as observed in the Topkapi Museum[64]. It is relevant and necessary to elaborate its role in the ongoing debate between the iconoclasts and iconodules over the past 2000 years, principally in the Christian Orthodox Church.

Part 2 of this series will present the secular icons in contrast to the religious icons of past centuries.

References:

[1] https://popculturemajor.com/pop-culture-icons-of-the-21st-century-the-figures-that-define-our-era

[2] http://www.byzantinecatholicchurch.org/index.html

[3] https://greekreporter.com/2024/05/29/istanbul-constantinople-both-greek-cities/#:~:text=Constantinople,%20originally%20founded%20as%20Byzantium%20by%20the%20ancient,under%20Sultan%20Mehmed%20II,%20and%20later%20renamed%20Istanbul

[4] https://www.britannica.com/place/Ottoman-Empire/Mehmed-II#:~:text=Under%20Sultan%20Mehmed%20II%20(ruled%201451%E2%80%9381)%20the%20dev%C5%9Firme,created%20at%20Varna.%20Constantinople%20became%20their%20first%20objective.

[5] Byzantine Iconoclasm – Wikipedia

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_Empire

[7] Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople – Wikipedia

[8] The First Iconoclasm – Search

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Council_of_Constantinople_(843)

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leo_III_the_Isaurian

[11] https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=leo+iii+the+isaurian+successors&qpvt=leo+iii+the+isaurian+successors&FORM=VDRE

[12] https://www.bing.com/search?q=The%20Papacy%20remained%20firmly%20in%20support%20of%20the%20use%20of%20religious%20images%20throughout%20the%20period%2C%20and%20the%20whole%20episode%20widened%20the%20growing%20divergence%20between%20the%20Byzantine%20and%20Carolingian%20traditions%20&qs=n&form=QBRE&sp=-1&lq=0&pq=the%20papacy%20remained%20firmly%20in%20support%20of%20the%20use%20of%20religious%20images%20throughout%20the%20period%2C%20and%20the%20whole%20episode%20widened%20the%20growing%20divergence%20between%20the%20byzantine%20and%20carolingian%20traditions%20&sc=0-194&sk=&cvid=676BB797AB824D9FA29DA3F10F996108#:~:text=About%20217%2C000%20results-,The%20western%20church%20remained%20firmly%20in%20support%20of%20the%20use%20of,reduction%20or%20removal%20of%20Byzantine%20political%20control%20over%20parts%20of%20Italy.,-Iconoclasm%20in%20Byzantium

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_popes

[14] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-review/article/carolingian-answer-to-the-iconoclastic-war-and-the-birth-of-western-art/520A7CA282F55CBAA92D8D7F05AF7CA7

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iconodulism

[16] https://massinitiative.org/what-was-the-iconoclast-controversy-and-what-caused-it/

[17] https://www.biblestudytools.com/bible-study/topical-studies/should-we-still-be-wary-of-graven-images.html

[18] https://www.christianity.com/wiki/holidays/why-is-jesus-mother-mary-called-theotokos.html

[19] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_Iconoclasm

[20] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Study_of_History

[21] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_Muslim_conquests

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_Iconoclasm

[23] https://www.worldhistory.org/Protestant_Reformation/

[24] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/icon

[25] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christ_Pantocrator

[26] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_Ages

[27] https://www.thecollector.com/byzantine-art-iconography/

[28] https://www.britannica.com/art/Renaissance-art

[29] https://www.etymonline.com/word/iconoclast

[30] https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/24871-osteoblasts-and-osteoclasts

[31] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/iconodule

[32] https://www.egyptinsights.com/king-akhenaten/#:~:text=Akhenaten,%20the%20pharaoh%20of%20Ancient%20Egypt%20during%20the,introduced%20a%20form%20of%20monotheism%20to%20the%20civilization.

[33] https://docslib.org/doc/7485781/symbols-of-the-french-revolution

[34] https://chineseorthodoxy.blogspot.com/2025/02/st-theodora-protectress-of-icons-feb.html

[35] https://www.byzantica.com/ladder-of-divine-ascent-at-saint-catherine-icon/#:~:text=Title:%20The%20Ladder%20of%20Divine%20Ascent%20Artist%20Name:,panel%20Location:%20Saint%20Catherine%E2%80%99s%20Monastery,%20Mount%20Sinai,%20Egypt

[36] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Ladder_of_Divine_Ascent

[37] https://orthodoxtimes.com/the-frescoes-of-the-chora-church-in-constantinople/#:~:text=The%20Chora%20Church%20in%20Constantinople%20(museum%20and%20from,the%20most%20important%20artistic%20creations%20of%20Byzantine%20art.

[38] https://www.christianiconography.info/harrowing.html

[39] https://www.choramuseum.com/

[40] https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=topkapi+palace+blue+tiles&qpvt=topkapi+palace+blue+tiles&FORM=IGRE

[41] https://istanbul.gottagoturkey.com/places-to-visit/mosques/cinili-mosque/

[42] https://toxigon.com/the-impact-of-the-byzantine-empire-on-european-culture

[43] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Mark’s_Basilica

[44] https://www.sainte-chapelle.fr/en/discover/the-bay-of-the-relics-of-the-sainte-chapelle

[45] https://www.aachenerdom.de/en/2025/03/13/the-cathedral-treasury-a-museum-with-unesco-world-heritage-status/

[46] https://www.thebyzantinelegacy.com/kunsthistorisches

[47] https://ancientcivilizationsworld.com/king-philip-ii-obsessive-collection/

[48] https://culture.pl/en/work/the-black-madonna-of-czestochowa

[49] https://catalog.obitel-minsk.com/blog/2018/07/mother-of-god-of-vladimir-story-of-one

[50] https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2023/papers/4

[51] https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2023/papers/4/

[52] https://academic.oup.com/book/5790/chapter/148969390

[53] https://www.magiscenter.com/blog/the-miracle-that-made-pope-john-paul-ii-a-canonized-saint

[54] https://www.academia.edu/17624319/Visualizing_the_Divine_An_Early_Byzantine_Icon_of_the_Ancient_of_Days_at_Mt_Sinai

[55] https://www.orthodoxhawaii.org/icons

[56] https://orthochristian.com/98876.html#:~:text=Today%20we%20commemorate%20one%20of%20the%20copies%20of,the%20Russian%20diaspora%20and%20many%20other%20Orthodox%20Christians.

[57] https://www.rbth.com/arts/333806-tretyakov-gallery-moscow

[58] https://www.ohiia.org/the-iveron-icon

[59] The Montreal Iveron Myrrh-Streaming Icon of the Mother of God / OrthoChristian.Com

[60] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Athos

[61] José Muñoz Cortés – Wikipedia

[62] https://catalog.obitel-minsk.com/blog/2017/11/the-history-of-montreal-iveron-icon-of

[63] https://www.biblestudytools.com/matthew/passage/?q=matthew+18:20-35#:~:text=20%20For%20where%20two%20or%20three%20gather%20in,tell%20you,%20not%20seven%20times,%20but%20seventy-seven%20times.

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: Easter, Peace, Peace art, Symbol

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 5 May 2025.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Peace Symbolism: Demystification of Icons, Iconodules, Iconoclasts and Iconography (Part 1), is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.