Process Documentation of Interfaith Peacebuilding Cycle: A Case Study from Nepal

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 6 Aug 2018

Prof. Bishnu Pathak – TRANSCEND Media Service

Abstract

4 Aug 2018 – The concept of this study was to explicitly define the characteristics of Process Documentation (PD), a unique type of record keeping system. The PD is a process of lessons learned-centric piloting approach which is a neologism in Social Science research. The PD moves forward “anti-clock-wise” direction and generally applies to humanitarian agencies in support, care and emergency relief programs to deliver basic services to needy people. The PD was first used in the Philippines in 1978, but applied in Nepal after peace accord 2007 to unite, reconcile and integrate the society through interfaith peacebuilding (IP) initiatives. The objectives were to document the process of the IP and analyze change perceptions contributing to transforming the ongoing conflict. The method led to interviews, storytelling, FGDs, observation and participation. The PD of IP generally functions through End-to-End Lifecycle that is organically similar to an ecosystem. Interfaith is not a religion, but a glorious art of symphony that makes a passage for peace, harmony, co-existence and friendship.

Introduction

“The fruit of silence is prayer; the fruit of prayer is faith; the fruit of faith is love; the fruit of love is service; and the fruit of service is peace.”

— Mother Teresa

Nepal is geographically sandwiched between two giants and long-term rival nations: disorderly undergoverned Republic of India and orderly over-governed People’s Republic of China. Nepal is squeezed by way of contrasting politico-ideology (system), identity (socio-cultural), resource, demography and mosaic Shangri-La. India executes bourgeois (elected representatives) democracy whereas China continues to use proletarian (selected representatives) democracy. Furthermore, Nepal has been surrounded by two economic mosaics. China controls the nation’s economy by political means whereas India’s politics are being controlled by business tycoons. It might not be a coincidence that the Free Tibet Movement was intensified in Kathmandu as long as the UNOHCHR and UNMIN were stationed in Nepal (Pathak, December 12, 2012, pp. 9-21). Both China and India apply self-centered ideology when having to look at Nepal. Strong, stable, progressive and developed Nepal makes close peace, peace dividend, co-existence and friendship relations with China, but weak, unstable, conflicting, and the least developed dependency with India’s power, politics and property. China, therefore, wishes to see stable, harmonious and prosperous Nepal that can control the Free-Tibet movement in its land, but India desires to keep Nepal unstable so India can easily control its politico-economy and natural resources in the name of insecurity and being escalated by extreme Muslim faith in Nepal.

Interfaith is not a religion, but makes a passage to reconcile peace, harmony and friendship among the religions. Interfaith is an involvement of persons of different religions for a societal noble cause. It creates a common platform to all who belong to different religious faiths. The religious faith begins within, between or among the set of personal beliefs. The liberal belief is that God is one, but his names are many; religion is one, but its traditional practices are many. Religion corresponds with spirituality and spirituality to humanity. There is one humanity, but humans are many. The paths of religion, spirituality and humanity emphasize the universal principles for empathy for the betterment of human beings. Thus, interfaith has a glorious symphony. It accepts, celebrates and delivers equal magnificence on faiths, colors, creeds, cultures and traditions of humankind. It morally understands the significant differences of persons and fulfills the quests of truth, justice and dignity. Thus, interfaith strengthens and respects reconciliation and friendship for peace-tranquility and harmony through peacebuilding initiatives. Interfaith can play a positive role in tackling intra-and-inter-religious conflict (Owen and King, 2013, p. 3) and enhance peacebuilding.

Peacebuilding is a comparatively new term (United Religious Initiative, October 2004, p. 10). Interfaith peacebuilding (IP) is a process that seeks to restore respect and mutual understanding between or among the people of different religions, e.g., Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, Judaism and Sikhism (Green, n.d., p. 16). IP has been an important tool to reconcile and make the divided society harmonious in post-conflict Nepal. It has played a significant role to restore retributive justice and restorative justice (Pathak, August 22, 2015). In post-conflict Nepal, the conduction of interfaith programs at grassroots levels is undertaken as problem solving and strategic intervention of peacebuilding at societal and community levels. In Nepal, the faith-based groups and religious actors have been contributing significantly for peacebuilding and development activities, particularly at grassroots levels (Owen and King, 2013, p. 3).

The aim of this study was to bring all religious and non-religious actors: peace and mediation practitioners, academics, journalists and social workers together to transform conflicting synergy to IP initiatives. Interfaith peacebuilding seeks greater understanding of ways to achieve effective, just and sustainable peace and harmony while rebuilding resilient societies after a period of conflict.

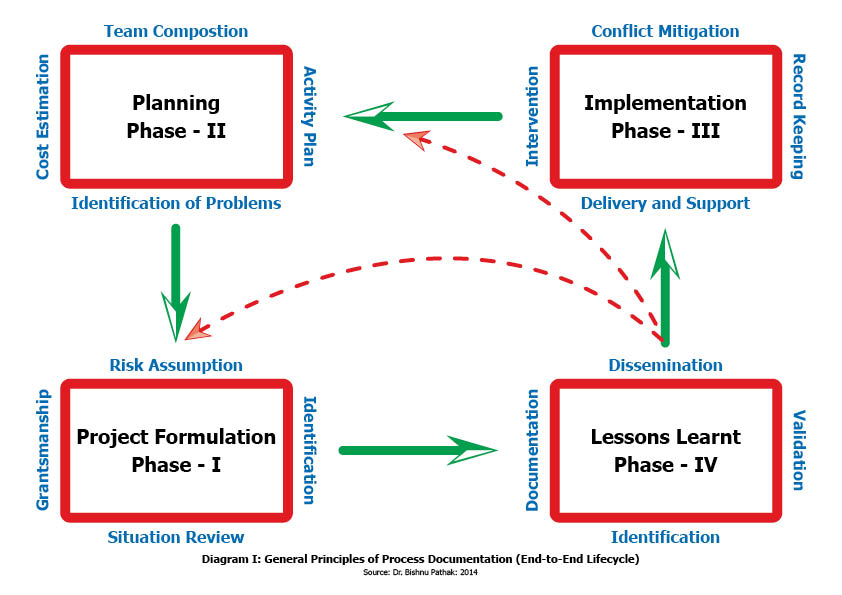

This study identified the Process Documentation (PD) used for documenting the process of learning adapted during IP initiatives that occurred throughout the project cycle (see Figure 1). Specific objectives were to document how interfaith networks and other beneficiary groups were formed; to gather information on how change perceptions contributed in knowledge, attitude and behavior of intended beneficiaries and different stakeholders; to document how challenges were mitigated and opportunities were utilized, and to identify bottlenecks and inefficiencies and lessons learnt from the project. Further, the approaches, strategies and policies of the process documentation were adapted to scaling up changes and relationship building.

The concept was derived to explicitly define the characteristics of PD and its processes. This is recognized as a unique type of record keeping system. The PD is a neologism that is being applied in Social Science research (De Los Reyes, 1984).

Regarding scope, the study was covered in two Morang (eastern) and Kapilbastu (western) districts in Nepal to assess the performances of IP at community groups or grassroots levels and identify the Process Documentation. The IP program was carried out in two variable scenarios: a post-conflict situation in Morang district by a local Community Development Forum (CDF) and during conflict in Kapilbastu by local Lumbini Christian Society (LCS) organizations. The interdisciplinary PD of the IP study was carried out for more than a year (2013-2014) with the close cooperation of United Mission to Nepal (UMN) cluster staff and partners. The study of IP was taken as a tangible case to resolve the encountered challenges through Local Capacity for Peace (LCP) program conducted by the United Mission to Nepal (UMN), a Christian community established organization (United Mission to Nepal, May 2009, p. 1).

The pioneer research was carried out as an empirical study. The empirical research was done pursuing direct and indirect observations and experiences along with participant observation. It used empirical qualitative evidences collecting information and data directly conducting open-ended structured interviews randomly selecting key informants, holding focus group discussions, collecting case studies and gathering existing documented materials and records, field diaries and newspaper clippings. Participant observation was also done to analyze the most significant gaps, challenges and overlapping practices. The methodology leads to a flexible, tangible and applicable positive impact process of documentation that focuses on the End-to-End Lifecycle (EEL) of the concerned peacebuilding efforts that is something organic, similar to an ecosystem. Secondary literature was also examined and reviewed to evaluate or support the primary data and information.

The gathered qualitative data were analyzed based on human security (collected security concept) norms and principles (UNGS, March 21, 2005, pp. 24-33). United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan said, “Freedom from want, freedom from fear and freedom of future generations to inherit a healthy natural environment are interrelated building blocks of human, and therefore, national security” (UNSG, 2000). The UN report on Human Security Now 2003 strives to protect the vital core of all human lives in ways that enhance human freedoms and rights and their fulfillment (Human Security at the United Nations, 2012). Thus, human security is a comprehensive, interrelated and coordinated concept of freedoms as fundamental rights (Pathak, September 2013, p. 1). It applies to conquering poverty, hunger, housing without a roof (no shelter), undress, disease, illiteracy, armed conflict and terrorism through mutual respect, harmony, prosperous and co-existence. All governments including Nepal are prime to ensure food, shelter, clothing and peace dividends for justice for everyone’s survival, livelihood, liberty and dignity (Pathak, March 17, 2014). On the other hand, this study gave the author freedom of movement, observation and participation to collect, scrutinize and analyze data freely. Thus, this study analyzes the data prioritizing freedom doctrines herewith.

Freedom of Process Documentation

The process of the Interfaith Peacebuilding leads to both theoretical understandings and practical considerations. The theoretical underpinnings describe some of the thoughts developed by scholars on the use of its general process. But practical characteristics particularize the impact made by the specific IP initiative in Nepal. However, both theory and practice follow the End-to-End Lifecycle process.

The international community pays attention to 36 percent of the world’s population, which lives either in deteriorating democratic or autocratic conflicting countries (Puddington and Roylance, 2016, p. 8). Increasing political polarization, with less ideological conflict but more identity power-based and prestige-centric interpretation, leaves significant and daunting development challenges. During the postconflict period, development agencies or humanitarian organizations launch support, care and emergency relief programs to deliver basic needs services to needy people without proper planning. However, the effectiveness and impact of the process of piloted project will be carried out or recorded at the end or during the project cycle by Process Development research.

Process Development (PD) is a principal tool used in social science research. The PD is a process of applying a lessons-learned-centric piloting approach (Joseph, n.d., p. 14) for the formulation of a largescale project. The PD provides a practical learning approach to manage necessary documentation systems (Quraishy, n.d.). David Korten defines the PD as a collection of data to provide learning and to check objectives (1980) and examine policy and implementation strategy (De Los Reyes, 1984). The term PD research was first used at a workshop in the Philippines in 1978 (Dongre, Mehendale, and Garg, September 2008, p. 15). India uses PD in its Community Health Program for tribal families (Chirmulay,1996, p. 56). UNICEF carried out PD as a decentralization tool for community participation in micro-planning in Maharashtra of India (UNICEF, 2003) and (Achrya, 1993). The process documentation applies to community people to encourage their participation in the livelihood and development program.

The PD is often uses in conflict-affected or post-conflict countries to empower the local or grassroots levels community for the transformation of contentious, troubling issues. The process tries to use local resources and local human capital. In many cases, the process uses a feasibility study or piloting phase to formulate future big projects. The PD has a definite lifecycle that begins at the end of project (as lessons learned) and moves in an anti-clockwise (right to left) direction unlike the universal tradition left to right cycle. It begins at the end of the project and completes at the end, and is called End-to-End Lifecycle, something like an ecosystem. It is a continuation process.

What does ‘End-to-End Lifecycle’ really mean? In general, the project lifecycle refers to the initiation, planning, implementation or execution and completion phases that move forward in a clockwise direction. But, the lifecycle of the PD usually moves toward the back, the anti-clockwise direction. A project has a temporary endeavor with a certain lifecycle. Such a lifecycle is usually constrained by a timeframe, funding, deliverables and particular roles and responsibilities of teams at societal levels. The PD helps to review, redefine and enrich the lifecycle of the project and introduce a new and bigger one (Pathak, 2010, p. 268).

The community-based interfaith program develops strategic planning which begins with project preparation, initiation, information gathering, visioning, modeling, planning and drafting and review pursuing definite lifecycle. Generally, a lifecycle is from the beginning to the end of specific project, succeeding one phase by another (phases VI to I). The cycle generally completes at the end in phase IV (see Figure I).

Figure 1. General Principles of Process Documentation (End-to-End Lifecycle)

- Lessons Learned: This is known as post-implementation review Phase IV which overviews activities, requirements, best practice (achievement), and gaps-overlaps and improvement. It has its own necessary processes: identification, documentation, validation and dissemination. It draws on both positive and negative experiences.

- Implementation: This is the main body of the program, called Phase III. It executes the objectives and activities specified in the proposal. It leads intervention, delivery and support, record keeping and conflict mitigation primarily. It further explores reporting, management, liaison and monitoring of the project. It reviews regular progress in facilitating and adjusting the plans if necessary.

- Planning: Planning happens in Phase II of the project cycle. The activity plan is identified, as are team composition, cost-estimation, activity plans and problem identification.

- Project Formulation: Project formulation is an inception of Phase I that begins with situation review; identification of issue: scope, objective and methods; grantsmanship and risk assumptions. Each individual phase follows initiation, preparation, continuation and completion of the activity.

To document the process of the given projects, the researcher tried hard to capture different opinions from the beneficiaries as they were expressed and drew lessons aiming to achieve consensus. This involved as many stakeholders as possible to reflect the experiences and perception of the wider community in the given context and aimed for participatory processes at all times as far as possible. The researcher collected only relevant information and drew on themes and trends rather than piling up heaps of information and reflected on situations and perceptions as they existed. The sole purpose of the Process Documentation is to maximize the positive impact for the future, more extensive, programs.

Freedom from Cultural Violence

The people of both Tarai (Madhesi) and the hills of Patthardehiya VDC of Kapilbastu district still remember the socio-cultural violence that erupted September 16-21, 2007. This violence was triggered when Abdul Mohid Khan, local landlord and President of the Democratic Madhesi Front (DMF), a cultural-based regional party, was murdered. The killing resulted in clashes between the Madhesi and Pahades (Tarai and Hill-Mountain dwellers) which finally turned into a Hindu vs Muslim conflict. The conflict killed 14 people, leaving several thousand displaced. There was widespread destruction, arson and looting including of five mosques and 200 houses.

On September 16, 2007, at 7:45 AM, Khan, a former leader of the Anti-Maoist Resistance Committee (AMRC), was travelling to Chandrauta on a motorbike. Another motorbike with three persons coming from the opposite direction stopped him at Balapur, Shivpur VDC of Kapilbastu. One shackled his hand, but another shot him to death by a gun. The socio-cultural tension spread like a wildfire while the rumor became public that Mohid was killed by those who wore Nepali dresses such as daura, suruwal and Nepali dhakatopi (a cap). It is still a mystery who was behind his killing.

The eruption of violence killed 8-pahade (Hindu) people from places in Patthardehiya, Ganespur, Bishanpur, Khahararia, Jobari, Jagadispur, Chandrauta, Khuruhuria, and Krishnanagar VDCs, etc. by the Madhesi and/or Muslim followers. They involved in looting, torching and vandalizing houses, shops and vehicles of pahade-dwellers with spears, khukuris (a Nepali sharp knife), home-made guns and bombs (Pathak, September 26, 2007, p. 1).

Scenario 1

Existing Situation of Women in Madhesi Community

There had been a community people meeting in Mahadehiya, one of the conflict-affected areas of Patthardehiya in summer 2008. They felt thirsty. They were trying to find a water pump nearby but suddenly one of the heads of the Chaudhary family requested that they drink water at his home. They went to Chaudhary’s home and stayed in the corridor. He went inside the house and told his family members to bring water for them.

The team initiated informal talks with Chaudhary about his family and business. Chaudhary was living in a joint family including his son, daughter, son-in-law, daughter-in-law etc. During the discussion, someone knocked on the door from inside. He went and brought glasses with a jar of water for them and served accordingly. Then he collected all glasses with the jar and he knocked on the door again in a similar way as it was done from inside earlier. He gave glasses to whoever had knocked from inside. They did not see and hear the voice of that person, but believed that she was a woman. The team was surprised and Cheli Gurung asked him, ‘who was the person who knocked on the door’? Why did s/he not come out? Chaudhary replied, “She is my daughter-in-law and has no permission to come out from the door. They have to do inside household work and we males do outside work.” Then Cheli shared her Pahaadi culture with him about how women serve water and tea for visitors and they are allowed to go outside the house and do other outdoor activities as well. He replied, “Our culture is different from yours and culture should be followed by everyone.”

In those ethnic and indigenous communities, women should stay inside the house and have to cover their face by the Saul or Sari. Women have no right to talk or see an unknown visitors’ face, moreover relatives too. Chaudhary added, “He had never seen the face of his daughter-in-law.” The team thanked him for the water and left his home. Cheli recalled, “I was bit surprised to know their culture and how women were kept inside the house, and being like a slave in the so-called name of ‘culture’.” (Personal Conversation with Cheli Gurung: December 11, 2013).

Four-days after the murder of Khan, a huge crowd of Pahade dwellers gathered and intensified their retaliation, attacking mosques and vandalizing and torching properties belonging to Madhesi or Muslim communities. Five Madhesis/Muslims were mercilessly killed in front of the police post of Jagadishpur, Patthardehiya. In Kapilbastu, it is estimated 6,000-8,000 individuals, mostly Pahades fled to the north, where the local population was predominantly Pahades. The majority of displaced Madhesis fled south, across the border to India (UNOHCHR, June 18, 2008, p. 8).

Most of the prominent parties’ leaders, Constituent Assembly I members and national and international human rights organizations condemned the killing of Mohid and socio-cultural violence eruption occurred thereafter. Richard Bennett, Chief of the UN Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights (UN OHCHR) in Kathmandu, condemned the violence through a press release on September 21, 2007 (UNOHCHR, 2007).

Similarly, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) condemned the killings and arson that had taken place in Patthardehiya and asked the government to bring the situation under control, considering the situation of deceased families, to offer relief to the victims and to ensure free health services (NHRC, September 21, 2007). Even Maoist-Supremo Prachanda strongly condemned the violence, murder, terrorism and arson and he noted the tensions as a conspiracy against the people’s desire for a republic and transitional peace (Kathmandu Post, September 22, 2007). The then Home Minister and leader of Government Talks, Team Krishna Prasad Sitaula, stated that it was a result of conspiracy and bad elements wanting to break social harmony and cohesion (September 21, 2007). The Cabinet condemned the violence, expressed its condolences to the victims and formed a high-level judicial commission to immediately provide relief to victims. The Commission submitted its report within four months, but the report has not been made public (UNOHCHR, June 18, 2008).

Unity in diversity among the caste-ethnic and religious population worsened, while some of the Tarai district including Kapilbastu formed the Pratikar Samiti (Anti-Maoist Resistance Committee) in June 2004. The Samiti received training from the Nepal Army. The Pratikar Samiti was very active in Kapilbastu under Mohid Khan’s leadership. During February and March 2005, violent clashes happened between the Samiti and the CPN-Maoist where 60 individuals of both conflicting parties were extrajudicially killed displacing thousands of civilians. The Nepal Army had established a post at Mohid Khan’s compound. Many people who were killed in September 2007 violence had also been targeted in 2005. While Pratikar Samiti was banned in September 2006, the Samiti became the Democratic Madhesi Front (UNOHCHR, June 18, 2008, pp. 3-4). The Pratikar Samiti were prejudiced against Pahade dwellers saying, “All Pahades are Maoists” (Budhi Ram Aryal, December 10, 2013).

Socio-cultural tension among the Madhesi vs Pahade and Hindu vs Muslim groups in Patthardehiya has been a three-decade-long phenomena. The tension between Madhesi and Pahade communities was initiated while the then Landless Commission formed by the Panchayat Government settled 250 landless Pahade families at Amlahawa of the same VDC in January 1984.

Some of Madhesi people who were against the Pahade settlement in their area cut down the dam for fishing in April 1984. While tension intensified between Madhesi and Pahade settlers, the Nepal Police intervened and settled the disputes, pardoning the Madhesi. While some Pahade women were going to Krishnanager (India’s border) to sell firewood, they were violently raped by Madhesis in retaliation in 1990. The present coordinator, Budhi Ram Aryal of Interfaith Peacebuilding Network, Patthardehiya and his Vinaju (brother-in-law) Jhabiraj Bhandari were also chased away by the Madhesis en route home from Krishnagar. Similarly, two teens from the Subedi family of 14 years were raped by a few Madhesis in 1995. These are a few examples of how socio-cultural violence often happened at Patthardehiya in the past.

During the conflict between Madhesi and Pahade in Patthardehia and Chandrauta on September 17, 2007, the Lumbini Christian Society (LCS) was distributing food and relief materials to those who had been displaced by flooding. A young Muslim who was bleeding profusely because his ear was chopped off was chased away by the Pahade Hindus. The injured one was saved with great difficulty. The LCS officials were astonished what had happened. Many fled from the scene. Immediately after that incident, a curfew was imposed in Butwal on September 17 and 18. The incident inspired the executives of LCS to do reconciliation and mediation work regarding the Kapilbastu massacre.

When officials of LCS visited Chandrauta, Bishanpur, Khraria, etc., on September 25, there were no Pahades in the houses and most of their houses were gutted. They returned and discussed the situation for a couple of days. On September 29, the LCS team visited Tripalnagar (Jagadishpurtal) where large numbers of displaced Hindu Pahades, including children, women, senior citizens and others were residing under the Tripals (temporary tents). They distributed mosquito nets and water pumps to them with the support of UMN.

For relationship-building, the LCS team contacted Muslim medical doctor Khaa and tried to convince him that they were Christian and desired mediation to restore peace. The doctor lobbied Muslim communities to initiate talks. When the LCS team received a green signal to meet them at Madrasa in Krishnanagar, they visited on January 3, 2008 and a meeting was held with Muslim leaders.

The LCS and UMN teams were amazed to see around 100 Muslims, including the son of Mohid, there. Muslim people clearly expressed both happiness and anger in front of them. The happiness was that Pahades were there for the first time to understand the real cause of conflict. The anger was that, after the massacre, most of the Muslims fled to India to save themselves from search warrants on charges of banditry, robbery, looting and among others. Ram Shankar Khatik, who was working as a mediator voluntarily on behalf of LCS, had also been among the list of arrests. Those displaced Muslims wanted to reunite with their families in the name of reconciliation.

Finally, a three-member Muslim committee of elite circle was formed, but failed to collect information from Muslims. Finally, they met with Balaji Prasad Chaudhary, local landlord at Jagadishpur, Patthardehiya VDC. With the support of Balaji, LCS initiated peace education for children, teachers and parents at both Madrasa and schools to enhance peace, harmony and security. They also made toilets at Madrasa and also constructed walls to separate class rooms at a school in Mainari in the name of Foundation for Peace.

LCS also worked in counseling for IDPs and conducted orientation programs for leaders at VDC level in December 2008. A total of 23 community leaders participated in rapport-building and interfaith network interaction in November 2009. From January 24-29, 2009, an exposure visit was conducted to India. Grassroots level orientation and a visit survey for peacebuilding work were also done in April 2010.

The direct meeting with both Pahade and Madhesi communities finally made fertile ground to establish an Interfaith Peacebuilding Network (IPN) at Patthardehiya on June 10, 2010. The beauty of the Network was that it was coordinated by a Hindu, but the deputy coordinator was Muslim and the member-secretary was Christian. Out of 15 members, it was comprised of ten Hindus, three Muslims and two Christians. The main objective of the Network was to bring people together on a common platform to reintegrate them into the society for technical support of the LCS.

Freedom in Interfaith Peacebuilding

The general objective focused on the process of learning adapted through interfaith peacebuilding initiatives and scaled up changes that had already taken place. The specific objectives of the IP led to change of perceptions through relationship-building in the community and that contributed to the interfaith peace network.

In Sunsari, the partner organization of the UMN used Safe and Effective Development action plan methods in pursuing Do No Harm (DNH) and Conflict Sensitivity Approaches to analyze and deliver peacebuilding services to the community (Regional Mainstreaming Process of LCP in South Asia, January-December 2011, p. 1).

It had been obvious that the decade-old armed conflict mostly victimized poor, vulnerable, disadvantaged and marginalized people at community levels owing to tight security in urban centers whose purpose was to protect elite people. Even the peace deal mostly remained at the elite centers, thus neglecting pains, suffering and grievances of people at grassroots levels. While the soul and spirit of all religions is to maintain peace and harmony in all urban to village levels, the community established IP Network (IPN) through dialogue. The district-and-VDC level religious followers generally had a deep faith, respect and appreciation for their respective faith leaders. Observing the socio-cultural uprising in Nepaljung and a few other local conflicting areas across Nepal, the religious leaders played significant roles to mitigate religious conflict.

Scenario 2

Self-Acceptance and Realization of Relationship Building

My name is Aatabul Mansuri, Coordinator of the IP Network, Morang, representing the Muslim faith. I have been involved in the IP Network for four years. Before becoming involved in the network, I had pride that my religion is superior to others. Owing to my negative perception of other religions, I did not invite faith leaders to any of our religious celebrations, festivals and social events or cultural cooperation events. I got an opportunity to participate on behalf of Muslim faith in the network. I then understood what different religions say about my faith. Moreover, they selected me as a Coordinator of the IP Network. The network worked and brought social harmony and mutual cooperation in the community. I used to lead regular meetings of the network to discuss how the existing situation and cooperation could be improved among the religions. We used to participate and celebrate co-feasts, exchange and share our interfaith greetings during the main festivals and conduct exposure visits at various holy places of the different religions. A culture of mutual respect was being accepted among the people and district people are realizing the importance of interfaith peace and harmony in public forums. Our stand is that each and every religion has a great contribution to make towards establishing sustainable peace and harmony in communities and societies. (Bishnu Pathak: 2013)

A two-day workshop on Interfaith and Inter-Cultural Dialogue was organized January 10-11, 2008 at Letang, Morang District, eastern Nepal. A peace lecture was delivered by four faith leaders: Hindu, Buddhist, Christian and Kirat. A total of 35 faith activists participated. The workshop selected 12 representatives or three individual representatives from each religion (Hindu, Buddhist, Christian and Kirat), and 15 from civil society to form the IP Network. The UMN officials facilitated the formation of the network, participating in the programs. The faith leaders participated on an individual basis rather than as representatives of their religious institutions.

The Muslim faith leader did not participate at first. Concerned officials of the organization met local Muslim faith leaders with a formal letter of invitation. They held a series of formal and informal, direct and indirect meetings regarding their participation. The Muslim faith leaders finally agreed to participate as they received a green signal from their respective leader or guru. A 35-member Central Committee of the IP Network was formed and a five-member VDC level committee consisting of one representative from each religion at each VDC: Letang, Pathri, Jaate, Kerabari, and Indrapur was established.

Prior to the formation of the IP Network, the partner organization of the UMN conducted an advocacy and awareness campaign on interfaith peace and harmony, strengthening interfaith groups at community and VDC levels. It had already formed Central and VDC level IP Networks. The activities of the IP Network at Letang, Indrapur and Pathari VDCs are given below:

- Conducting regular meetings,

- Interacting with IP Network,

- Conducting class on IPN education in schools,

- Establishing Interfaith Peace Parks in schools,

- Conducting free interfaith health camps at Indrapur,

- Formation of village and VDC-level IPN at Letang, Pathri, Jaate, Kerabari and Indrapur,

- Documentary of celebration on National and International Peace Day,

- Participating in festivals and exchanging and sharing of good wishes and grievances,

- Publishing and distribution of peace calendars, posters and pamphlets,

- Exposure visit in several places,

- Skill and capacity enhancement training to marginalized communities,

- Seed money provided to conflict victims after training,

- Exchanging and sharing of experiences at national and international levels,

- Livelihoods campaign in favor of IP network,

- Information dissemination, and

- Relief and peace education campaign.

The Network started any formal program or activity by following religious traditions of worship. The IPN had formed at three levels: Community (,village), VDC and Central levels. The village-level IPN had created in Letang, Pathri, Jaate, Kerabari and Indraput VDCs, which selected one representative from each religion at the centre. The principle work of all networks of interfaith peacebuilding were to resolve troubled issues that exist in the community, VDC and at District levels. The process for IP what they adopted during programs were remarkable.

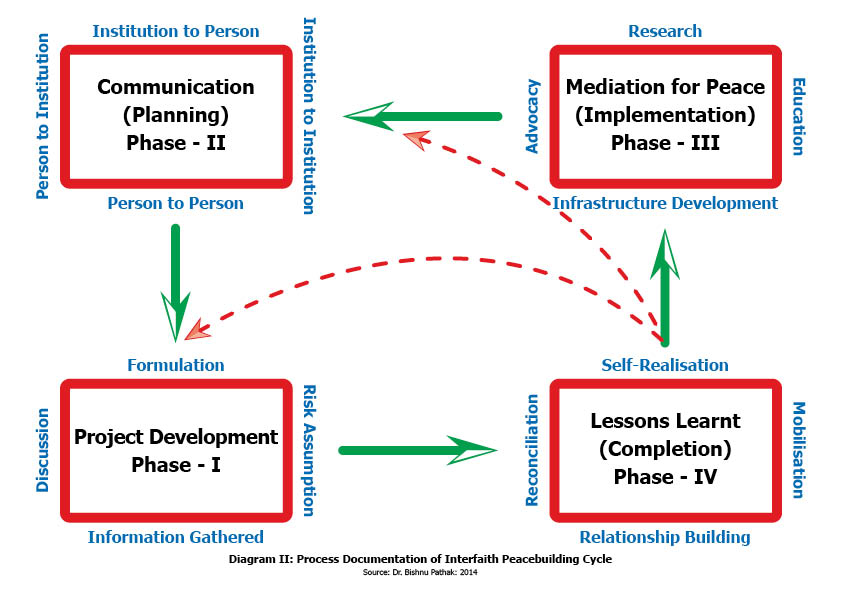

- Lessons Learned: The post-implementation phase of the Process Documentation of the IP Cycle followed the right-to-left (anti-clockwise) direction in Morang and Kapilbastu districts. The process documentation of the project begins after the completion of the (piloted) project as illustrated in Phase IV in the cycle diagram (see Figure 2). It is just the opposite of the normal project cycle. Relationship building, self-realization, reconciliation-forgiveness and mobilization are the principal findings of the study on this Phase. Figure 2 is no less than a Theory of Change for the IP Networks of the project.

- Implementation: Mediation for peace was initiated through advocacy, research, education and small scale infrastructure development in the implementation, Phase III. UMN’s partner was involved in advocacy on IP, health, intergroup communication, mass-media and budget-aiming to influence public policy, resource allocation procedures and decision-making. For that, both organizations further engaged in public speaking, commissioning, lobbying and campaigning.

Both the CDF and LCS networks engaged in formal and informal education to enhance knowledge, skills and habits through workshops, training, interaction, etc. LCS was supporting both public schools and the Madrasa in Patthardehiya. District and regional level workshops on forgiveness and reconciliation were conducted at Patthardehiya. CDF engaged in peace education in public secondary schools and in the construction of peace parks and students’ peace clubs. A total of 22 community leaders received community mediation skills. Seven teachers and 17 community people, including school management committee members and leaders, learned peace education skills. Fully 110 Christian leaders participated in forgiveness and reconciliation workshops during Phase III in Patthardehiya.

A two-day workshop was finally held in January 2008, conducted by CDF, where faith leaders ultimately realized the need for a common platform to transform the conflict. At first, four faith leaders, Kirat, Buddhist, Hindu and Christian, agreed to sign the deal and formally established the IP Network. The Muslim representative joined the IP Network later and drafted its Code of Conduct (CoC).

In Morang, a total of 225 members formed nine peace groups. Similarly, 20 members from conflict victims formed facilitation groups for peace. Two Children’s Peace Clubs in Shikshya Bikash Secondary School, Letang and Laxmi Secondary School in Karabari were formed. Interaction programs for interfaith peacebuilding were conducted in six VDCs: Letang, Jaate, Belbari, Kerabari, Pathri and Indrapur.

LCS and its IP Network engaged in small scale infrastructure development. There were 115 school students and 90 students of the Madrasa studying in peaceful and safe environments when the author reached that location. A total of 71 toilets were built in the community after conducting an awareness workshop on health and sanitation education on December 2010 in Pathardaiya. Moreover, 53 toilets had been constructed in Madhesi communities and 28 in Pahade communities.

Figure 2. Process Documentation of Interfaith Peacebuilding Cycle

- Planning: Phase II mostly focused on communication of the peacebuilding project’s objectives that began by finding out social prestige in the community. Process documentation involved person to person, person to institution, institution to person and institution to intuition communication following “indirect and informal, direct but informal, indirect but formal, and direct and formal” dimensions. The communication phase involved discussion with faith leaders and other pertinent stakeholders.

- Project Development: Phase I was initiated through project development, searching out information on IP Initiatives at structural, personal and institution levels. It focused on discussion of the project in the team, project formulation and risk assumptions. The project formulation was a proposal writing phase that includes scope, objectives, method, budget and limitations.

The process of decision-making on peacebuilding initiatives was shared between the heads of institution and partner organization. The decision-making process was applicable from grassroots to VDC, District, Regional, National and International levels. When the establishment of the IP Network was completed, other issues and initiatives such as religious visits to faith leaders were initiated, one after another.

Generally, the PD of any contentious issue relating to interfaith peacebuilding began from lessonslearned and completed its circle again at the end of the project lifecycle (Phase IV), which is simply called the End-to-End Lifecycle. Commenting on the formation of the network, the central leader of the IP Network from the Islamic faith, leader Sajaan Miya, said, “The Interfaith Peacebuilding is a good program. When the Network ends one contentious issue through dialogue, another issue comes or appears like a cycle. It would be better if we could establish this very important Network early.”

In Patthardehiya, the Network members received five-day mediator training in May 2011, including income generation, leadership and group mobilization training, distribution of educational materials, street drama, interaction with the local peace committee, peace rally, International Peace Day celebration, etc. from 2011 to 2013. Beneficiaries included 1,029 people comprising 530 males and 499 females. Also, 50 people with disability (30 males and 20 females) directly benefited from the peacebuilding program.

Some changes of perception were observed during the study of PD. Perceptual changes were found in the structure of programs, issue identification, institutions and individuals’ interpretations on peace, conflict and coexistence. Perceptual changes greatly influenced relationship building from institutional to individual levels. Relationships were no less than building blocks that were mostly applicable in societies and communities. The following true and successful case study on the Process to Common Ownership of Misbahul Ulum Madrasa will help to clarify the cause.

In regards of clockwise direction of IP Cycle process, President Mustafa who is also a member of the IP Network in Patthardehiya put forward a proposal to construct the roof of the Misbahul Ulum Madrasa to the IP Network as Phase I. The Network approached at LCS to financially support the Madrasa as Phase II. Finally, the roof was constructed with the financial support of LCS and UMN – that is called Phase III. All students are now studying safely under the roof as Phase IV in terms of process documentation.

The Kadiya Madrasa of Patthardehiya-4 was initiated with the amount of Rs 20 Nepalese currency under the leadership of Mohammad Mustafa Mushalman some 20 years ago. The Madrasa had been conducting classes in Urdu and normal public school courses with the support of muthidan (fist-grant) from 10 families. They erected a wall of brick and mud, but could not construct the roof. The IP Network Patthardehiya, with the support of LCS, provided rods and cement and the roof was constructed. One toilet was also made. A total of 107 children comprising 23 Urdu students, 44 boys and 40 girls were studying from grade 1 to 5 classes in a hall without separation of classes. More interesting is that 13 Hindu children were also studying Urdu. There are only two (one Maulana and another Hindu) teachers. The Hindu teacher taught English, Math, Nepali, Social Science and Science to all students and Urdu was taught by the Maulana (Urdu teacher). However, the Government did not provide a single teacher. The students who read Urdu generally came in the morning and other students later in the day.

Scenario 3

IP Network Builds Relationship Between Pahade and Madhesi

I, Budhi Ram Aryal migrated to Amlahawa in Patthardehiya VDC along with my parents in January 1984 when the Landless Commission provided 18 Kattha of land to our family. The Government settled us at Amlahawa, relocating from a forest area of Barganga VDC of Kapilbastu. I myself observed confrontations with a few Madhesi people immediately after our arrival in Patthardehiya. I was only just saved from some Madhesi people who attacked several occasions.

I lost any hope of staying at home after I had been a witness of socio-cultural violence between MadhesiMuslim and Pahade-Hindu dwellers in September 2007. I was discouraged further when large numbers of Pahade people left their homes and properties fearing possible attack and assassination by Madhesi dwellers.

The situation was so terrible and fearful that if I visited a Madhesi family or neighbor(s), they felt suspicious of me as a Pahade spy, and Pahade people also looked at me suspiciously, wondering whether I secretly worked for the Madhesis. When Madhesi friends or neighbor(s) visited my home or talked to me, I myself felt unsure, wondering whether they were spying on me and my family. Our earlier brotherhood and neighborhood relations between Madhesis and Pahades were absolutely broken, during and post September 2007 violence.

In the meantime, I met with the officials of Lumbini Christian Society and UMN. Their skillful motivation and training helped us to establish an IP Network in Patthardehiya. The Network is formed comprising representatives of all communities and I am working as a coordinator of it. We have now avoided all kinds of conspiracy theories and share our thoughts that unity is our strength, which further strengthens our relationships. We are made aware of society’s bad elements as well. We can now resolve differences if any tension arises in our communities. Even police officials ask for our support to mediate family tensions and other conflicts. I have now fully reversed my earlier thoughts to leave my home, land and place. It is all because of the IP Network. The Network has been an instrument of reconciliation for all the arising local confrontations. (Personal Conversation: December 10, 2013, Jagadishpur, Patthardehia VDC, Kapilbastu).

Nepal is dominated by the Hindu religion. However, the Constitution of Nepal 2015 declared Nepal a secular state. To respect and maintain religious harmony, the Government declares national holiday even for a small populace ethnicity such as Kirat. Thus, Nepal maintains unity in diversity from village to nation.

While several media, including BBC and ABC TV, highlighted the faith leaders’ visit and meeting with the Kirat faith leader Atmananda Lingden at Larumba, the birth place of the Kirat religion founder Ram Bhakta Kurumbang in Ilam District, Eastern Nepal on December 4, 2011, the UMN’s Sunsari Cluster broadcast 21 episodes of a Vox Pop Radio Program through Saptakoshi FM, Itahari. The peacebuilding programs included interfaith peace speeches, community mediation, peace celebrations and meetings of faith leaders. Such programs were demanded from many surrounding villages and districts as well.

These contributions generally led participants to know how beneficiaries were encouraged by positive changes taking place in knowledge, attitude, behavior and context after the introduction of IP programs in Morang and Kapilbastu districts. The case of Sabitra Siwakoti (in Scenario 4) is itself a good example of how an individual change was attained in attitude and behavior. Where she belongs to an institution, definite change can be measured.

Scenario 4

Change in Attitude and Behavior

Sabitra Siwakoti – aged 25, of Belbari, was recruited by the Community Development Forum, Letang in Morang district as a Coordinator to operate the IP Project. That was her first assignment. Previously, she had emotional and aggressive behavior. She herself admitted that her attitude and working behavior gradually changed over two years (2011-2013) period. Now she can control her emotion and aggression. She uses to easily listen others’ criticism of her. Rather than immediately defends herself through arguments, she herself thinks thoroughly what were the reasons behind such critics and responds them constructively. (Personal Conversation: October 19, 2013, Morang).

Before formation of the IP Network, each faith leader had a competitive pride and an intolerant view that his religion was superior to others. Each faith leader had suffered from a superiority complex. Interreligious debate never happened.

An inauguration of Higher Secondary School at Letang was a good example that all religions are the same and their sole purpose is to respect senior citizens, love children and support needy people to maintain brotherly relations for peace, coexistence and harmony in society and the universe. Indeed, dharma is the eternal law, the awakened one, the anointed one, self-discipline and governance (Pathak, 2005). Previously, political leaders and elite people were invited on such occasions and received recognition. The following case study of inauguration by faith leaders jointly is itself the indicator of change in the society.

In clockwise direction process documentation, both informal and formal communication was held between CDF and administration on the inauguration of Higher Multiple Secondary School at Letang. The officials of CDF and the school administration reached on a conclusion to inaugurate the school jointly by the faith leaders. CDF called informal meetings of all faith leaders for the purpose and all unanimously accepted the proposal as process Phase I. The school administration finally sent the formal invitation letter to faith leaders for their participation in the inauguration program as Phase II. The rally was organized and separately, led by each religious leader following their customs (with dress), traditions, banners and play-cards as Phase III. The rally was enthusiastically, and with some surprise, watched by the people across the road. The inauguration was initiated at the dais, performed through the religious worshipping of one faith leader followed by another: Muslim, Buddhist, Christian, Kirat and Hindu faith leaders respectively. The last successful Phase was IV.

It was a unique occasion for all in general when all faith leaders gathered on a common platform and prayed for good wishes to all students, teachers and parents.

Another success story is the Children’s Peace Club, Laxmi Secondary School, established at Bhaluwa, Kerabari VDC in Morang District in 1967. The School ground was used as grazing land by the surrounding communities for their livestock, mainly cows. Both teachers and students felt uneasiness because of the noisy surroundings and cattle and cattle-dung around the school.

In 2008, UMN’s partner CDF asked the school administration to establish a Peace Park. The school organized a meeting of students, parents and teachers and decided to establish a park. Finally, the Children’s Peace Club formed and built Interfaith a Peace Park with the support of the CDF. The Peace Park has portrayed a statue of all five faiths existing there. Thus, students, teachers and parents felt comfortable.

A successful conflict transformation case study is taken as a good example of community mediation. Harka Bahadur Rai and Haikam Singh Tamang, inhabitants of Letang – 1 migrated from the Northern part of the same Morang district in 1975. They jointly bought two acres of land and divided it equally. Both neighbors lived there harmoniously for a long time. Then the newly-constructed gravel road separated the land boundaries of both, decreasing Tamang’s land area by 1 kattha. Some portions of Tamang’s western site were flooded by the Chisapani River; however, he extended his 11 Kattha boundary onto ailanni (public open) land. When Rai passed away, his son Bhoj Bahadur Rai asked why Tamang had 1 Bigha and 10 Kattha land compared to 1 Bigha for the Rai family. Bhoj confronted his neighbor Tamang, stating that he took advantage of his innocent and docile father Harka Bahadur. The community tried to resolve the dispute at local level, but the case was filed at Police Post and finally at the District Court. The division of land issue caused sharp quarrels and physical beatings.

In December of 2011 Haikam Singh went to the house of the Hindu faith leader and community mediator Hari Prasad Kafle to reconcile the case. Kafle called a meeting of both conflicting parties along with a few civil society members. Using mediation techniques that he gained from the CDF training, Kafle developed several alternatives. Finally, both agreed to divide 11 Kattha ailani land: 4 Kattha to Rai family and 7 Kattha to the Tamang family. Instead, Bhoj Rai delivered 1 Kattha registered land to Tamang. Thus, the decade-old conflict was settled with a win-win situation. Both families were found very much happy living with harmonious relations when Kafle visited in June 2012.

Besides, the coordination, coexistence and cooperation are developed among the religious groups. The Medina Masjid of Ujinagar, Patthardehiya Ward No. 1 had been operating without a roof for two years. The Hindu inhabitants, namely Ram Shankar Khatik, the IP Network member, tried hard to construct a concrete roof for the mosque, frequently visiting and requesting VDC secretary of Patthardehiya. Khatik to ask local Muslim Maulana Jammu Miya to file an application at the VDC office. The Village Council finally accepted the demand and released the required funds. Another Hindu activist, Ayodhya Khatik, provided pebbles and sand free of charge. The Muslim faith leader of Medina appreciated what the Hindus did. He said, “We really appreciate the good wishes and are very much indebted to Hindu people who voluntarily cooperated to construct the roof. We safely pray and worship God Allah in our Mosque now”. “We are aware of bad elements who took advantage of Muslim-Hindu communal violence in post-September 2007. We condemn such violence and we are now united despite our caste/ethnicity and socio-cultural background,” he further stated.

Interfaith peacebuilding encountered challenges too. The officials of CDF and LCS and faith leaders were confused “where they lost?” at the beginning of programs. Even a single religion such as Hinduism has many sub-branches such as Shaivites, Vaishnavas, Smarthas and Shaktism. If the leader of one branch of the faith accepted an invitation to make a speech, there was a high chance of criticism by another branch of the same religion. There was huge distrust, fear and anxiety within, between and among the faith leaders and their followers at the beginning of Network formation. Some people wondered whether the IP Network would be proliferating Christianity. On the other hand, some wondered whether the Network would establish a new religion. The Muslims believed on symbol of a moon, but the Hindus to a sun. There were still some signs of the concept of superiority.

It was very hard to find an official representative of a faith to participate in the program from any respective religious institution. Moreover, faith leaders were often influenced by political parties. Such political influence leaves a societal impact, as most of the communities are divided under the various umbrellas of politics. The impact of this phenomenon is equally difficult to realize publicly. The dissemination of information through media is necessary, but it may create considerable tension if information is twisted intentionally or innocently.

Scenario 5

Support to Conflict Affected Woman

My name is Maina Dhimal and I live in Letang Village. The 10 years of People’s War in Nepal have deeply affected my life. My husband died during the war, and I had to take responsibility for my family – two daughters, one son and my mother-in-law. I had a piece of land which I had kept mortgage, to get a loan to feed my family and for my children’s education. So I had been facing many difficulties to make my family survive.

One day the CDF suggested me to contact the District Administration Office with evidences in order to receive relief support being affected by the Maoist launched People’s War. I followed their advice and I visited there seeking for help. Finally, I received financial support. With that support, I was enabled to get my house and land back.

Besides, the CDF assisted me to find a job of teacher in the Shiva Shakti Child Center. CDF has provided educational materials for my children and given seed money for income generating activities. I am earning regularly and am an active member of a group for conflict-affected people. Compared with previous years, I have peace and happiness in my life and I desire to support other people like me. (CDF: October 20, 2013, Morang).

LCS vice president Padam Bahadur Dhami received a life threat from Balaji Chaudhary at the beginning of the IP initiatives. He said, “If you are supporting Madhesi communities, it is fine, but if you go against them, you will be killed.” When Balaji understood the objectives of LCS, he helped them what he could do. However, Balaji was critical about how much financial help LCS received from UMN. On the process of registration to LCS, the then CDO Dhruba Wagle on August 13, 2006 said, “You have already made Christians in Butwal.” And a further comment, “Are you now looking for legitimacy for it?”

If faith leaders received appreciation or displeasure from the community people, it directly left impacts on its coordinating institutions: CDF, LCS and UMN. A competitive relationship between the IP Network and CDF began immediately after the network formed. The faith leaders used to say, “Why should we engage voluntarily that much with the CDF IP program while there are staffs for this job.” The Network of Morang wanted to mobilize their human resource capacities establishing their office bypassing CDF and UMN. Also faith leaders felt inferior as the programs were coordinated by CDF officials.

While faith leaders have gained more social recognition compared to the NGO officials, the IP Network desired to function independently by establishing its own identity-based institution. Registration in the IP Network was not easy as it had its own specific norms, values and mandate to restore peace and harmony in society and there were certain restrictive government provisions as well. It is to be noted that ‘if the belly is hungry, neither individual nor institution can bring peace nor restore harmony through networks and mediation alone’.

Participation of the community in the IP Network depended upon their socio-political exposure, education, openness and family background. In urban centers, people are easily gathered for meetings, but poor countryside people often avoided attending. Even the faith leaders used to say, “Conflict is a political issue that could be resolved nationally. Interfaith peace could resolve family and communitybased socio-cultural conflicting issues alone.” The local religious leaders and other followers feared that religious conflict might erupt, while Christianity influenced large numbers of poor, marginalized, disadvantaged and vulnerable people in this poorly developing country Nepal.

The political leaders seemed shortsighted and guided by vested interests. They just wanted to have short-term benefit only. Even in the past election for Constituent Assembly II 2013 in Kapilbastu, the Madhesi Janaadhikari Forum Nepal, a culture-based political party candidate Abhishek Pratap Shah said, “I do not need the votes of Pahade and Hindus people” at the gathering of Muslims. But in another gathering Shah said, “We do not need the votes of Pahade, but Muslims and Hindus only.” When Pahade asked Shah why this was said, he replied, “That was just elections strategy and tactics to vote him making them happy.” He finally won the CA II election. Such selfish-centered and provocative politics may invite fearful communal violence in the future. Also, there is a high expectations of faith leaders from the NGOs. If their hopes and expectations cannot be fulfilled, friendly relations among themselves shall turn hostile at any time.

Freedom to Attain Lessons Learned

At the beginning of the program, one faith leader proposed construction of 3-4 toilets in schools rather than mobilizing resources for peace at community levels. But, the same leader later realized the importance of interfaith peacebuilding and its network in Morang. Moreover, out of 71 toilets constructed in Patthardehiya, 4-5 toilets were not used. Some people said that the toilet may contaminate the drinking water and that if people drink it, they will die. Similarly, a few other families did not use the toilets, fearing conversion of their religious belief to Christianity as it is supported by the UMN. Rajendra Gupta of Patthardehiya said, “I feel shame when I go to the toilet.” Such opinions were shared, owing to lack of understanding and use of toilets among poor communities. Some of the important lessons learnt through the IP activities are given below.

- Relationship Building: Relationships have been enhanced among the various religious groups at grassroots, district and regional levels. At the beginning, one Muslim leader of Patthardehiya asked LCS officials to provide them a Bible to understand what was written there on peace and harmony. Besides, he further asked why Christians and Hindus wanted to help Muslims. However, the relationship between that man and the LCS team was improved through peace talks later.

- Realization of Importance: The faith leaders gained experiences and mutually exchanged/shared about the importance of religious and understanding one another. Exposure visits were also conducted in Larumba, Lumbini and Gujarat-Hyderabad in Kirat, Buddhist and Hindu religious places, respectively. The demand for “schools as a zone of peace” helped students understand the importance of peace and harmony.

Scenario 6

Self-Realization of How Change Occurred in Woman

My name is Cheli Gurung, Peace Coordinator, UMN Cluster, Rupandehi. I have been involving in peacebuilding initiatives immediate after the socio-cultural violence Madhesi vs Pahade and Muslim vs Hindu happened.

In the initial phase after the Kapilbastu massacre, UMN and LCS completed numbers of visits, holding meetings with both Pahades and Madhesis for rapport-building and situational analysis to support, care and provide emergency relief to victims. Among many visits, I particularly remember one meeting of June 3, 2008 at Jagadishpur in Patthardehiya, where the people refused to listen to me and my voice. UMN and LCS had organized a meeting with the Madhesi community. Around sixty men with only one woman (who used to go to the community to sell bangles) from the Chureta community participated that meeting.

It was very difficult and challenging to start a conversation with them due to language problems and their suspicious eyes looking at us. They all seemed very aggressive, emotional or angry, chewing betel-leaf and eager to know our plan, especially the financial (budget) part. Firstly, we did introduce each other. Most of the participants were teachers, political leaders, local traders and conflict victims. With much courage, I started to give my introduction and I was amazed that nobody was looking towards me; their face was towards my male colleague. I thought that they did not understand my language. Then I started speaking in mixed languages in Hindi, Nepali and Bhojpuri. After completing my introduction, I sat down in a chair. Then they started to watch me. Again, I thought that I am the only woman participating from the Pahade community, so they were looking at me and later on I ignored it.

LCS shared their organizational introduction and it was my turn to share. I stood up and shared my organizational introduction in mixed languages, which was easy to understand for them. I looked over them and again I found that they were not listening or were ignoring me. I was a bit surprised but anyway I finished my part and my colleague helped to summarize the meeting. Later, I talked with that one lady about the reaction of participants towards me. She replied, “In this community females have no right to go out and talk in a similar way as males”. Men especially did not want to listen to women and discourage them to involve and participate in meetings and outside activities. I was again surprised to know the reason why they did not listen me. I understood the causes for the lack of participation of women in meetings for their own development, leadership and standing for their rights. It was an amazing experience for me.

The situation is changed now. Women’s participation is increased in group meetings, community development works and various types of activities at community levels. The integrated community focused program for peacebuilding is increasing with participation of women, children and other community people. Because of half-decade old peacebuilding programs, women are empowered, women are encouraged, women are participated, women are changed and women are transformed. (Personal Communication with Bishnu Pathak: December 12, 2013)

- Respect: The interfaith peace program enhanced the respect within, between and among the faith groups. For instance, Hindu, Islam, Christian and Buddhist faith leaders visited Larumba (eastern Nepal) and saluted Kirat Dharma Guru (respected person) Atmananda Lingden, touching his knee in a program on December 4, 2011 on the course dealing with respect for a Guru.

- Culture of Peace: The faith leaders enhanced their reading culture of IP through exchanging and sharing of holy books with each other to understand more on peace, reconciliation and harmony. The culture of peace during the massacre at Kapilbastu was very much damaged. In some cases, the flesh of pigs was thrown in the Masjid and at cows in the temple. Both sides later understood how selfish-centered perpetrators had compelled them to fight one another.

- Bottom-Up Approach: The culture of peace experimented with following the interests and desires of people at grassroots levels, which is widely known as bottom-up approach. This approach is against Nepal’s top-down traditional policy for peace and co-existence.

- Program Acceptance: In earlier days, urban center people easily accepted the invitation of interfaith, realizing its importance, but poor people at community-level did not feel comfortable attending such program. In recent years, even local faith leaders easily accept the invitation because of peace advocacy launched, focusing on them.

- Perception Changed: The earlier concept of “Islamists are terrorists” has gradually been changed when other faith leaders and commoners got an opportunity to understand them, being involved and participating with them. The Students Association at Peace Club succeeded in stopping a child marriage, exerting pressure on their parents and community.

- Acceptance of Co-Existence: The former gap existing within, between and among Hindus, Buddhists, Muslims, Christians and Kirat was reduced at local levels. Now the IP Network has been a common platform for all existing religions. Faith leaders have developed self (individual) respect and freedom which is gradually transmitting to the common masses. Even Madhesi communities are now aware not to arrange child marriage and not to demand/deliver dowries. The IP put forward a guru mantra, that is “Do No Harm”.

- Community Mediation: Faith leaders were involved in reducing differences and/ or resolving the longstanding conflicting or contentious issues. Mediators enhanced their skills and capacity by attending community mediation training and other workshops. Even police officials have written letters (to mediators) to settle disputes at local level. Self confidence among the faith leaders has been is enhanced.

- Consensus Building: Consensus building is being enhanced at grassroots, VDC and district levels. There had been a long discussion about putting the logo of all five locally-existing religions in the poster in Morang. The designed logo was finally approved after several rounds of formal and informal discussions and communications. This approval was possible as the concerned faith leaders introduced one single objective. That was to establish or deliver non-violence, peace, coexistence and harmony in society.

- Participation: All faith leaders’ joint participation in co-feasts and other cultural activities were made public. In Morang VDCs, the Government-established district-based Local Peace Committee included one representative from the IPN as a member. Even in Madhes, 15-20 percent of women have attended meetings, speaking and listening carefully to NGOs. The local mediator Sarita G C of Patthardehiya said, “Earlier there had been a trend that whoever was clever and talkative would win the case, but now the real victims get justice and the perpetrator is penalized.”

- Relevance: The IP Network has been developed as a role model of community mediation and facilitation to restore peace, harmony, co-existence and social justice. The hope of people has gradually been increasing more with the IP Network than with local police officials. Even the police post looks to support from the IP Network to provide 3-4 bicycles to patrol the community. IP programs have been relevant to change people’s traditional mindset: regular use of toilets, health and sanitation.

The IP Network celebrates key religious events together and creates a conducive environment for peace, supporting secularism. The united events helped to mitigate the very cause of conflict in society. The Network uses the method of reconciliation and builds brotherly-sisterly relations. The interfaith peacebuilding program relies on Theories of Change.

It is to note perceptual changes that have taken place among faith leaders due to formation of IP Network, peacebuilding advocacy, regular meetings, exposure visits, empowerment training on peace speeches and community mediation, conduction of IP education programs, establishment of a peace park, celebration of peace day, respectful participation in festivals, exchange and sharing religions books, among others.

Conclusion

Interfaith peacebuilding has brought broader structural, institutional, societal and personal cooperation at local levels. It pursues socio-cultural conflict transformation by peaceful means though dialogue, mediation, media advocacy and exchanging-sharing. Besides, the IP has been an alternative of the society-community in local levels and Village Development Committees in the absence of the elected committee for 20 years.

The process should follow a clockwise direction for future, larger programs, unlike an anti-clockwise process to support and care for emergency and relief programs. The process documentation was introduced as learning-by-doing through action research, advocacy, peace education, exchanging-sharing and reporting.

It is to be noted that Madhesis took longer time to understand interfaith peacebuilding as compared to Pahades. The Madhesis have a language problem as well. They tend to rely on their own Mukhiya (Head) of the community where Pahades often make decisions independently. The Madhesis often hesitate to share their experiences within their own community, unlike the Pahades. Pahades specify what the project they need are, but Madhesis more rely on budget allocations. The socio-cultural diversities seem sometimes opportunities and sometimes constraints, similar to the connectors and dividers of peace.

The self-confidence of the faith leaders has been increased. The prior competitive attitude and behavioral mind-set of “my religion is superior” that existed within, between and among religious leaders has constructively changed.

There is a need for more integrated work. Integrated program will be only one solution for longlasting IP and the process of the PD will be more easily understood. Thus, interfaith peacebuilding at community-level is no less than “to the people, for the people and by the people”. This is a bottom-up approach rather than a typical top-regular hierarchical development project approach.

Any project can develop in one of two ways: first, regular (traditional or hierarchical) project development or second, irregular (pilot) project development. The process documentation method is in the second category. In some cases, it is called project reflection. Process documentation is a new social science development phenomenon. The DP generally applies in developing countries, particularly at community level, to resolve contentious or troubled issues, empowering grassroots-level communities, encouraging indigenous techniques and utilizing local resources. It aims to facilitate lessons learned in the change process through action research. It eliminates mistakes, cutting down time, reducing costs and improving the quality of efficiency for a particular task or activity of a given project.

Process documentation shows the techniques of implementation, evaluation and monitoring of community based interfaith peacebuilding initiatives that ultimately improve the quality of organizational services. The method of process documentation is flexible to make it applicable to a variety of programs in socio-cultural, political and economic fields. Process documentation has an inbuilt participatory process to encourage peacebuilders. Interfaith peace is itself benevolence, governance and discipline.

References:

ABD. (2012). A Peace building Tool for a Conflict Sensitive Approach to Development: A Pilot Initiative in Nepal. Kathmandu

Achrya B., Verma, S., and Tandon, R. (1993). Process Documentation in Social Development Program Mimeo. New Delhi: Society for Participatory Research in Asia (PRIYA).

CBS. (2014). Population Monograph of Nepal. Volume II (Social Demography). Kathmandu.

CDF. (n.d.). Code of Conduct of Interfaith Peace Network. Morang.

Central Bureau of Statistics. (2012). National Population and Housing Census 2011. Kathmandu.

Chirmulay D.C. (1996). Workshop Report: Process Monitoring and Process Documentation: BAIF’s Community Health Program. Pune: MDMTC.

Church’s Auxiliary for Social Action. January 2005-December 2007. Internal Assessment Report On Regional Mainstreaming of LCP Approach In South Asia. New Delhi.

De Los Reyes, R. P. (1984). Process documentation: social science research in a learning process approach to program development. Philippine Sociological Review: 105-120.

Dongre, A.R, Mehendale, A.M., and Garg, B.S. (2008). Process Documentation in Health Research. MGIMS, 13(ii)

EED PME. (2011). EED Key Requirements for Project Proposals. New Delhi: Church’s Auxiliary for Social Action.

EED. (2008). United Mission to Nepal LCP Consolidated Report 2005-2008. New Delhi.

Green, A. (n.d.). Interfaith Dialogue. Columban Mission Institute. Retrieved from http://www.ceosyd.catholic.edu.au/Parents/Religion/RE/Documents/Interfaith%20Dialogue%20Presentation%20-%20SOR%20Focus%20Day%20.pdf

Human Security at the United Nations. (2012). New York: Human Security Unit.

Joseph, J. A. (n.d.). Process Documentation. New Delhi: Jawaharlal University.

Kathmandu Post. (2007). Kathmandu: Kantipur Publication, September 22.

Kofi, A. (2000). We the Peoples: The Role of the United Nations in the 21st Century. New York: United Nations.

Korten, D. (1980). Community Organization and Rural Development: A Learning Process Approach. Public Administrative Review: Institute of Philippine Culture.

LCP South Asia Network. (2013). Evaluation of “Local Capacities for Peace” Project in South Asia (2005-2012). Draft Report, August.

Owen, M. and King, A. (2013). Religious Peacebuilding and Development in Nepal. UK: University of Winchester.

Parthasarthy R. (1994. Lift irrigation scheme in Zadka village: Documentation of the process of implementation. Ahmedabad: Aga Khan Rural Support Program.

Pathak, B. (2005). Politics of People’s War and Human Rights in Nepal. Kathmandu: BIMIPA Publications.

Pathak, B. September 26, 2007. Kapilvastu’s Socio-Cultural Violence. Kathmandu: CS Center, No. 49. Retrieved from http://www.cscenter.org.np/uploads/publication-/110627101930_Situation%20Update%2049%20Kapilbastu.pdf

Pathak, B. (2010). “Approaches to Peace building in Nepal”. Experiments with Peace. Oslo: Networkers – South North.

Pathak, B. (2012). “Transitional Security”. Transitional Justice. 1(5). Kathmandu: TJRC.

Pathak, B. (2013). “Transformative Harmony and harmony in Nepal’s Peace Process”. Gandhi Marg. 35(1).

Pathak, B. (September 2013). “Origin and Development of Human Security.” International Journal of Social and Behavioral Sciences. Vol. 1(9), pp. 168-187.

Pathak, B. (November 1, 2013). Exploring Future Peace building in Nepal. Kathmandu.

Pathak, B. (2014). Human Security and Human Rights: Harmonious to Inharmonious Relations. TRANSCEND Media Service, March 17. Retrieved from https://www.transcend.org/tms/2014/03/human-security-and-human-rights-harmonious-to-inharmonious-relations/

Pathak, B. (2015). Enforced Disappeared Commission: Truth, Justice and Reparation for Dignity. TRANSCEND Media Service. August 22.

Puddington, A. and Roylance, T. (2016). “Anxious Dictators, Wavering Democracies: Global Freedom under Pressure”. Freedom in the World 2016. New York: Freedom House.

Quraishy, Z. (n.d.). Process Documentation. Dept. of Informatics. Norway: University of Oslo. Retrieved from http://docslide.net/documents/1-process-documentation-dr-zubeeda-quraishy-dept-of-informatics-university.html

Regional Mainstreaming Process of LCP in South Asia. (2011). Annual Progress Report. Kathmandu: United Mission to Nepal.

Shrestha, T. B. (2003). November 2003. Dharma. USA.

UNGS. (2005). Report of the Secretary-General on In larger freedom: towards development, security and human rights for all. New York. A/59/2005

United Mission to Nepal. (2005). PISA Program Status Report. Kathmandu.

United Mission to Nepal. (2006). Regional Mainstreaming Process of LCP in South Asia. Annual Progress Report. Kathmandu.

United Mission to Nepal. (2007). Regional Mainstreaming Process of LCP in South Asia. Annual Progress Report. Kathmandu.

United Mission to Nepal. (2008). Regional Mainstreaming Process of LCP in South Asia. Annual Progress Report. Kathmandu.

United Mission to Nepal. (2009). LCP Consolidated Report 2005-2008. Kathmandu.

United Mission to Nepal. (2010). Regional Mainstreaming Process of LCP in South Asia. Annual Progress Report. Kathmandu.

United Mission to Nepal. (2011). Regional Mainstreaming Process of LCP in South Asia. Annual Progress Report. Kathmandu.

United Mission to Nepal. (2011). Strategic Plan 2010-2015. Kathmandu.

United Mission to Nepal. (2012). Local Capacity for Peace. CASA Annual Report. Kathmandu.

United Religious Initiative. (2004. Interfaith Peacebuilding Guide. Retrieved from http://www.uri.org/files/resource_files/URI_Interfaith_Peacebuilding_Guide.pdf

UNICEF. (2003). Process Documentation on Micro planning: Helping communities to take charge. Mumbai.

UNOHCHR. (2008). Investigation by the OHCHR in Nepal into the violent incidents in Kapilvastu, Rupandehi and Dang districts of 16-21 September 2007. Kathmandu. Retrieved from http://nepal.ohchr.org/en/resources/Documents/English/reports-/HCR/2008_06_18_KAPILVASTU_Report_E.pdf

UNOHCHR. (2009). OHCHR urges Government to address Kapilvastu violence two years on. Retrieved from http://nepal.ohchr.org/en/resources/Documents-/English/pressreleases/Year%202009/September2009/2009_09_07_PR_Kapilvastu_E.pdf

Veneracion, C. C. (Ed.). (1989). A Decade of Process Documentation Research: Reflections and Synthesis, Based on the Proceedings of the Seminar-Workshop on Process Documentation Research Held on 21-24 January 1988 in Tagaytay City, Philippines. Institute of Philippine Culture, Ateneo de Manila University.

________________________________________________

Bishnu Pathak is a Senior Commissioner, Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons, Kathmandu, Nepal. Pathak is a Ph.D. holder in conflict management and human rights, president and director of the Conflict Study Center. He is a Board Member of TRANSCEND International for Nepal and also a BM of the TRANSCEND Peace University. Besides writing the book Politics of People’s War and Human Rights in Nepal, he has published a number of research articles on issues related to Human Rights, UN, Security, Peace, Civil-Military Relations, Community Policing, and Federalism. E-mail: pathakbishnu@gmail.com

Bishnu Pathak is a Senior Commissioner, Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons, Kathmandu, Nepal. Pathak is a Ph.D. holder in conflict management and human rights, president and director of the Conflict Study Center. He is a Board Member of TRANSCEND International for Nepal and also a BM of the TRANSCEND Peace University. Besides writing the book Politics of People’s War and Human Rights in Nepal, he has published a number of research articles on issues related to Human Rights, UN, Security, Peace, Civil-Military Relations, Community Policing, and Federalism. E-mail: pathakbishnu@gmail.com

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 6 Aug 2018.