No Direction Home: The Journey of Frantz Fanon

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER, AFRICA, HISTORY, LITERATURE, 6 May 2019

Adam Shatz | Raritan Quarterly, Rutgers University – TRANSCEND Media Service

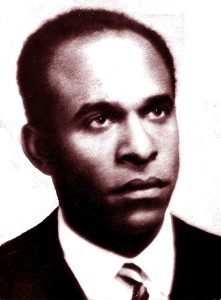

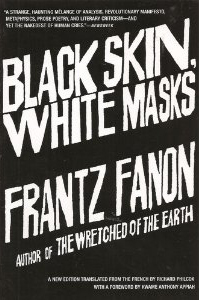

Winter 2019 – I was a teenager when I first saw a picture of Frantz Fanon, on the back of my father’s hardcover copy of Black Skin, White Masks, a 1967 Grove edition. He appeared in a tweed jacket, a freshly pressed white shirt, and a striped tie, with a five-o’clock shadow and an intense, somewhat hooded expression; his right eye slightly turned up to face the camera, his left fixed in a somber gaze. He seemed to be issuing a challenge, or perhaps a warning, that if his words weren’t heeded, there would be hell to pay.

Who is this man? I remember thinking. The jacket explained that he had been born in Martinique in 1925, had studied psychiatry in France, had worked at a hospital in Algeria during the French-Algerian War, and had eventually joined the Algerian independence struggle, becoming its most eloquent spokesman, before dying of leukemia at age thirty-six. I was intrigued by the way that Fanon connected different worlds—France, the West Indies, North and sub-Saharan Africa —and by the link that he forged between psychiatry, a discipline devoted to care and healing, and revolution, an attempt to transform the world by means of creative destruction.

I was no less intrigued by where I found Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth, often described as the Bible of decolonization. In the small library of radical literature that my father kept in our basement, Fanon’s books were sandwiched between The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Isaac Deutscher’s The Non-Jewish Jew: the former a classic memoir of black nationalism, the latter an essay on socialist internationalism. This location may have been an alphabetical accident, but the more that I read Fanon, the more I became convinced that he belonged in between the political traditions broadly represented by Malcolm X and Deutscher; that he spoke to their questions, their tensions, and, not least, their internal contradictions.

“I do not come with timeless truths,” Fanon writes in his introduction to Black Skin, White Masks. But when I began reading him, in the late 1980s, during the death throes of the apartheid regime in South Africa and the eruption of the first intifada in occupied Palestine, his observations about the humiliation of colonial domination and the psychological dynamics of anticolonial revolt had lost none of their immediacy. Not surprisingly, his work was undergoing an extraordinary revival in the university, where he was being rediscovered — in a sense discovered for the first time — as a major thinker of postcolonial modernity, rather than as a propagandist of violent revolution, or as the “theoretician” of the Algerian Revolution.

Since then, Fanon’s work has made significant inroads beyond the academy. There are allusions to, and echoes of, Fanon in the writing of Kamel Daoud, Claudia Rankine, Ta-Nehisi Coates, John Edgar Wideman, and Jamaica Kincaid; in the art of Glenn Ligon, Isaac Julien, and John Akomfrah; in the cinema of Ousmane Sembène, Raoul Peck, and Claire Denis; even in jazz and hip-hop. (The trumpeter Jacques Coursil, a Martiniquan trumpeter and linguist, draws on passages of Black Skin, White Masks in his haunting oratorio Clameurs.) His name has also been invoked by members of the Black Lives Matter movement, in part for its talismanic aura, in part because Fanon’s writings on the vulnerability of the black body apply with eerie power to the extrajudicial killings of young black men. In the aftermath of Eric Garner’s death by chokehold, the contemporary resonance of Fanon’s remark that “we revolt … because … we can no longer breathe” hardly needs to be spelled out.

The power of Fanon’s writing lies not only in its perceptiveness or topicality, but in its unusual rhetorical force. Fanon was somewhat ambivalent about appeals to emotion. In this he was very much a product of the French schooling system. His mentor at the Lycée Victor Schoelcher in Fort-de-France was the writer Aimé Césaire, who had taken part in the creation of the Négritude movement with his fellow poet Léopold Senghor, later Senegal’s first president. But Fanon was skeptical of Négritude’s lyrical claims about a shared black consciousness that unified Africa and the diaspora, and he especially recoiled from Senghor’s claim that “emotion is Negro just as reason is Greek.” He aimed, rather, to dismantle the edifices of racial prejudice and colonialism in a French of classical rationality. Yet for all his fierce disagreements with Césaire, Fanon remained his disciple, and both his first book, Black Skin, White Masks, and The Wretched of the Earth contain passages of feverish prose poetry. As he explained to the philosopher Francis Jeanson, who edited Black Skin, White Masks and would later become Fanon’s ally in the Algerian liberation struggle, “I am trying to touch the reader emotionally, which is to say, irrationally, almost sensually …. Words have a charge for me. I feel incapable of escaping the bite of a word, the vertigo of a question mark.”

Reading Fanon, one sometimes has the impression that mere expository prose cannot do justice to the impulsive movement of his thought. I use the word “movement” advisedly: Fanon did not write his texts; he dictated them while pacing back and forth, either to his wife, Josie, or to his secretary, Marie-Jeanne Manuellan (who has just published a memoir about the experience). This method of composition lends his writings an electrifying musicality: restless, searching, and, as he fell prey to the leukemia that would kill him, otherworldly in its call for a new planetary order, cleansed of racism and oppression. The black British filmmaker John Akomfrah set his remarkable portrait of Stuart Hall to the music of Miles Davis. Were he to make a film about Fanon, he would surely set it to Coltrane, whose classic quartet was formed the year that Fanon died, and who died just six years later. Fanon’s sentences remind me of Coltrane’s famous “sheets of sound”: cascades of arpeggios, rapid, dense, ever in pursuit.

Forged in perpetual movement, Fanon’s writing holds up a mirror to his peripatetic life. He was not, by profession, a writer. He was a doctor, and later a revolutionary spokesman and diplomat. Yet nothing, arguably, mattered to him more than writing. For someone who left Martinique at twenty-one, never to return; who was expelled from Algeria, his adoptive country, at thirty-one; and who spent his last five years as a revolutionary exile roaming throughout North and sub-Saharan Africa, writing was his only home.

It was his way of wrestling with the problems he confronted in his difficult, dangerous life. Albert Memmi, a Tunisian-Jewish psychologist and critic of colonialism who was in many ways Fanon’s foil, described Fanon’s life as “impossible.” Perhaps it was. But there is no doubt that Fanon chose his life, as much as it is possible to do so. In that sense, Fanon’s life bore little resemblance to those of his contemporaries and friends, anticolonial patriots like Patrice Lumumba of Congo, Felix Moumié of Cameroon, and Abane Ramdane of Algeria, all of whom sought to liberate their countries from foreign domination. Fanon, by contrast, never considered returning to Fort-de-France, and felt disappointed, even betrayed, that Césaire, his mentor, had campaigned for Martinique to become a department of France, rather than an independent country. Not long before he died, Fanon confessed to Simone de Beauvoir that he dreaded becoming a “professional revolutionary,” and spoke movingly of his desire to set down roots. But where? That was the problem. He was a man without a country—except a country of the future, or of the imagination. As painful as this must have been to Fanon, his statelessness, the migratory nature of his life, has lent his writing a uniquely global relevance that the speeches of Lumumba and Moumié noticeably lack, and that not even the work of his great Martiniquan peers, Césaire, Edouard Glissant, and Patrick Chamoiseau, can match.

Fanon’s career as a revolutionary psychiatrist has given his writing an irresistible allure, but this peculiar intimacy of life and work has also been the cause of considerable misunderstanding. Healer, soldier, martyr: much of the literature on Fanon amounts to little more than a praise song. As an icon of “Third World” resistance, Fanon has been adopted by groups as various as the Black Panthers, Palestinian secular guerrillas, Islamic revolutionaries in Iran, and the alienated banlieusards of France, who feel as if the Battle of Algiers never ended, but simply moved to the metropole. Lost in this process of sanctification have been the complexities of Fanon’s life; the unfinished, ambiguous, sometimes agonized nature of his writing, particularly its relationship to the Western tradition; and, not least, the ironies and contradictions that history would impose on his words. Lost, too, has been the central thrust behind Fanon’s life and work: not the struggle against French rule in Algeria, but the struggle for what he called “dis-alienation,” the emancipation of people’s repressed capacities and the achievement of a humanism worthy of the name.

Fanon bears some responsibility for the abuse of his writing. He contributed many of the jingles that would later provide Third World liberation struggles with its exhortatory soundtrack. The slogan for which he is best known, however, is one that he did not write, the claim that “killing a European is killing two birds with one stone, eliminating in one go oppressor and oppressed: leaving one man dead and the other man free.” It was Jean-Paul Sartre, not Fanon, who wrote this, in his famous preface to The Wretched of the Earth, a powerful critique of Eurocentrism that, alas, did no service to Fanon’s reputation by exulting in self-flagellation and celebrating terrorism as a kind of Dionysian carnival of the oppressed.

In fact, violence was never Fanon’s remedy for the Third World; it was a rite of passage for colonized communities and individuals who had become mentally ill as a result of the settler-colonial project, itself saturated with violence and racism. His clinical work was the practice that underpinned his political thought. He considered colonialism a deeply abnormal relationship; the colonizer and the colonized were locked together—and constructed—by a fatal dialectic. There could be no reciprocity, only war between the two, until the latter achieved freedom. But this was no more a “celebration” of violence than Hegel’s account of the master and the slave, which inspired it.

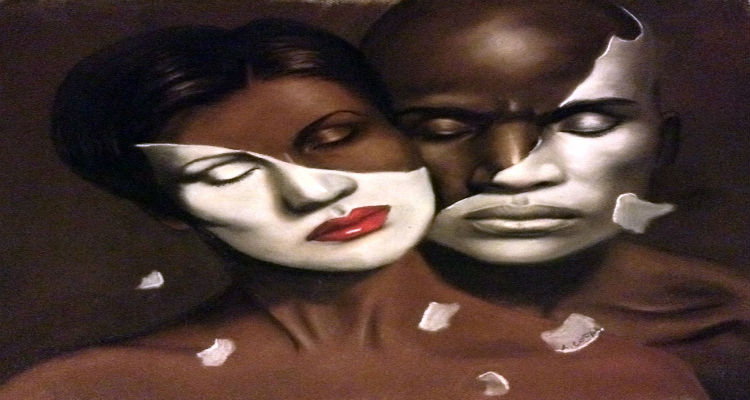

The other charge often leveled against Fanon is that he was a defender of what, today, we call “identity politics,” a black nationalist who insisted upon the irreducible “fact of blackness,” the supposed life force of black authenticity. In fact, Fanon saw blackness not as a fact but as the phantasmagoria of a racist white society: “the fact of blackness” was a misleading translation of l’experience vécue du noir, “the lived experience of the black man.” Fanon regarded Négritude as a “black mirage,” a flight into an imaginary, mystical past, a retreat from a future that remained to be invented. The solution to being forced to wear a white mask was not, for Fanon, proudly adopting a black mask. As a student he was so determined to overcome Césaire’s shadow that his first writings, allegorical plays deeply indebted to Sartre, altogether avoided the topic of race. Even as he became an advocate of revolutionary struggles in the Third World, he remained highly critical of nostalgic attempts to revive traditional African culture.

That Fanon has been so widely misread makes a kind of poetic sense. For mis-recognition, and the violent alienation it produces, is the plot on which most of his work turns. His first important psychiatric paper, published in 1952 in Esprit, described the psychosomatic distress experienced by North African workers in France. Perplexed by their accounts of pain without lesion, French doctors had concluded that these men suffered from cerebral and cultural deficiencies. Fanon saw their illness very differently: “they have had France squeezed into them wherever, in their bodies and in their souls,” only to be told, “They are in ‘our’ country,” a reproach that the French-born descendants of these men are still hearing today.

Nor was Fanon himself immune from racism, as he discovered not long after arriving in Lyon in 1947. Raised by middle-class parents in Fort-de-France, he had fought and nearly died serving in the Free French Forces, and received the Croix de Guerre with a bronze star. He had worn the same uniform as the metropolitan French, unlike the Senegalese members of his battalion, the so-called tiralleurs sénégalais. As far as he was concerned, he was a West Indian French man, from a respectable home. “Negroes” were Africans, and he wasn’t one of them. He had even made a point of studying in Lyon, rather than in Paris, one of the capitals of the Black Atlantic, since he wanted to be somewhere “more milky.”

In milky Lyon, however, a little white boy saw him pass by and cried out: “Look, maman, a Negro! I’m afraid.” The experience of seeing himself being seen—of being fixed by the white gaze — provided Fanon with the primal scene of Black Skin, White Masks. Although he found his life partner in a left-wing, white French woman — Marie-Josèphe Dublé, known as Josie — he described his life in Lyon as a series of what, today, we would call microaggressions, from patronizing compliments on his French to well-meaning praise of his mind.

What Fanon suffered in his encounter with the little boy on that “white winter day” was, as Louis Althusser puts it in his classic essay on ideology, the experience of being “hailed” or “interpellated.” That this primal scene takes place outdoors is crucial to its power. As Althusser writes: “what … seems to take place outside ideology (to be precise, in the street), in reality takes place in ideology. What really takes place in ideology seems therefore to take place outside it.”

Fanon was not a follower of Althusser, much less a philosophical antihumanist, but in Black Skin, White Masks he attempts to do something that Althusser might have appreciated, namely demonstrate the way that ideology interpellated French West Indians as racialized subjects. Black Skin, White Masks is not a memoir, but it is obviously the product of Fanon’s time in Lyon, his first experience as a member of a black “minority.” Interestingly, two of the chapters explore how racial ideology disfigures interracial relationships, a subject that would have been of acute personal concern to Fanon.

The problem of “love” in a racist society lies at the heart of Black Skin, White Masks, nearly as much as it does in the work of James Baldwin, who in 1956 would hear Fanon address a conference of black writers organized by Présence Africaine in Paris. Baldwin, who sailed to Paris a year after Fanon arrived in Lyon, does not mention Fanon in his report on the conference, but he would later invoke Fanon in his 1972 book No Name in the Street. The title of Black Skin, White Masks could have been Notes of a Native Son, for Fanon, like Baldwin, was grappling with the obstacles to black citizenship in a white-dominated society. His principal quarrel in the book is not with colonial domination and exploitation, but with the racial limits of French republicanism: it is a Frenchman’s hopeful protest for inclusion, not a bitter repudiation of the métropole. Fanon seems confident of his ability to achieve “nothing short of the liberation of the man of color” not only from white supremacy, but from the restrictive conceptions of Négritude: “The Negro is not. Anymore than the white man.” Fanon’s language here should be familiar to anyone who has read Sartre’s 1946 essay Anti-Semite and Jew, which argues that the idea of “the Jew” as the Other was an invention of the anti-Semite. For Fanon, a person of African descent became black, became a “nègre,” through and only through the white gaze. The so-called black problem was no less a phantasm than the Jewish question.

Yet Fanon was not content simply to dispatch with race as an analytic concept, and to prove that it is a mere construction, unlike, say, class. This argument has had its liberal defenders, including the political philosopher Mark Lilla, who, in a widely cited New York Times op-ed article (later expanded into a book, The Once and Future Liberal), belittled what he called “diversity discourse” as an “identity drama” that “exhausts political discourse” and divides a polity that could otherwise be unified around supposedly real things like “class, war, the economy, and the common good.”

In Fanon’s view, however, race is always already a refraction of ideas, fears, and anxieties about “class, war, the economy, and the common good.” It is a fiction, yet one so pervasive and so powerful as to produce profound real-world effects. It may seem to be “a very trivial thing, and easily understood,” as Marx wrote of the commodity, but “it is, in reality, a very queer thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.” Like the commodity, race is the ghost in the machine of an apparently disenchanted society, never fully exorcised, a tribute not only to enduring inequities but to the enduring power of the gaze, of unreason and ressentiment. And its worst injuries, for Fanon, are psychological: violations of dignity, especially the “shame and self-contempt” it implants in its victims. Even a relatively privileged, “assimilated” black man like himself was “damned”: “When people like me, they tell me it is in spite of my color. When they dislike me, they point out that it is not because of my color. Either way, I am locked into the infernal circle.” But how was he to liberate himself from this infernal circle and — as Ta-Nehisi Coates puts it in Between the World and Me — “live free in this black body”?

Looking to free himself from the white gaze, Fanon was briefly drawn to the racial romanticism of Senghor, tempted, he says, to “wade in the irrational,” as the Négritude poets had urged him. When he read Sartre’s introduction to Black Orpheus, a 1948 anthology of Négritude poets, he was taken aback by the condescension: Sartre defended black consciousness as an “antiracist racism”—what Gayatri Spivak would later call “strategic essentialism” — but downgraded it to a “weak moment in a dialectical movement” toward a society free of race and class oppression. Yet by the end of Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon has come to agree. The “only solution,” he declares, is to “rise above this absurd drama that others have staged around me” and “reach out for the universal,” rather than seeking refuge in some “materialized Tower of the Past.” If anyone is making that leap, he adds, it is not the Négritude poets, but the Vietnamese rebels in Indochina, who are taking their destiny into their own hands.

Fanon’s dissatisfaction with the political moderation of the Négritude movement, and with his mentor Césaire, who had become a senator in the overseas department of Martinique and an opponent of independence, may help to explain one of the great mysteries of his life: his decision not to return home to Fort-de-France after completing his residency at the psychiatric hospital of Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole in the Massif Central. François Toscquelles, Fanon’s mentor at Saint-Alban, was both a doctor and a resistance fighter, having headed the Spanish Republican Army’s psychiatric services before crossing the Pyrenees in 1939. He had pioneered institutional or social therapy, which tried to turn the hospital into a recognizable microcosm of the world outside. The idea underlying social therapy was that patients were socially as well as clinically alienated, and that their care depended on the creation of a structure that relieved their isolation by involving them in group activities.

In 1953, after more than a year at Saint-Alban, Fanon took up his post at Blida-Joinville, a psychiatric hospital about forty kilometers south of Algiers. He was responsible for 187 patients: 165 European women and 22 Muslim men. He found some of them tied to their beds, others to trees in the park. They lived in segregated quarters, with the women in one pavilion and the men in another. The hospital’s former director, Antoine Porot, the founder of the so-called Algiers School of colonial ethnopsychiatry, had justified this segregation on the grounds of “divergent moral or social conceptions.” Several of Fanon’s colleagues shared Porot’s view that Algerians were essentially different from Europeans, suffering from primitive brain development that made them childlike and lazy, but also impulsive, violent, and untrustworthy. As a West Indian atheist who was neither a Muslim “native” nor a white European, Fanon stood at a remove from both the staff and the residents at Blida. Since he spoke no Arabic or Berber, he relied on interpreters with his Muslim patients. His closest friends in Algeria would be left-wing European militants, many of them Jews.

To instill a sense of community among the staff—and perhaps to break out of his solitude—Fanon created a weekly newsletter. In a striking article published in April 1954, he questions the spatial isolation of the modern asylum, anticipating Foucault’s 1961 Folie et déraíson: Histoire de la folie à l’âge classique:

Future generations will wonder with interest what motive could have led us to build psychiatric hospitals far from the center. Several patients have already asked me: Doctor, will we hear the Easter bells? … Whatever our religion, daily life is set to the rhythm of a number of sounds and the church bells represent an important element in this symphony …. Easter arrives, and the bells will die without being reborn, for they have never existed at the psychiatric hospital of Blida. The psychiatric hospital of Blida will continue to live in silence. A silence without bells.

Restoring the symphonic order of everyday life was the goal of social therapy, and Fanon pursued it with his usual vigilance, introducing basket weaving, a theater, ball games, and other activities. It was a great success with the European women, but a total failure with the Muslim men. The older European doctors told him, “when you’ve been in the hospital for fifteen years like us, then you’ll understand.” But Fanon refused to understand. He suspected that the failure lay in his use of “imported methods,” and that he might achieve different results if he could provide his Muslim patients with forms of sociality that resembled their lives outside. Working with a team of Algerian nurses, he established a café maure, a traditional tea house where men drink coffee and play cards, and later an “Oriental salon,” as he put it, for the hospital’s small group of Muslim women. Arab musicians and storytellers came to perform, and Muslim festivals were celebrated for the first time in the hospital’s history. Once their cultural practices were recognized, Blida’s Muslim community emerged from its slumber.

Fanon’s curiosity about Algeria led him far outside the hospital gates. Deep in the bled of Kabylia, the Berber heartland, he attended late-night ceremonies where hysterics were healed in “cathartic crises,” and learned of women using white magic to render unfaithful husbands impotent. He discovered a more merciful attitude toward mental illness: Algerians blamed madness on genies, not on the sufferer. In his writings on these practices, Fanon never uttered the word superstition. Yet even as he insisted on the specificity of North African culture, he was careful to avoid the essentialism of the Algiers School. He wanted to pierce the frozen, apparently natural surface of reality, and to uncover the ferment beneath it.

On 1 November 1954, that ferment erupted, when the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) carried out its first attacks, launching a war of independence that would last for nearly eight years. The FLN was a small organization that had grown out of a split in the banned Movement for the Triumph of Democratic Liberties, a group led by the founding father of modern Algerian nationalism, Messali Hadj. Winning over the Muslim majority to its cause, and, not least, persuading them that they had a chance against one of the world’s most powerful militaries, required no small effort and no little coercion. Their case would partly be made for them by massive French repression: the razing of entire villages, the forced relocation of more than two million to “regroupment” camps, widespread torture, and thousands of summary executions and disappearances; as many as three hundred thousand Algerians died during the war. Fanon, however, needed little convincing. When the rebels contacted him in early 1955, he had already chosen his side; according to his biographer David Macey, his first thought was to join them in the maquis.

Fanon took great risks to help the rebels, opening the hospital to FLN meetings, treating fighters at the day clinic, and forbidding the police from entering with their guns loaded. At the same time, he was treating French servicemen who were involved in torturing suspected rebels. He did not hand over their names to the FLN for they, too, were victims of a colonial system whose dirty work they were required to perform. Eventually, however, Fanon concluded that he was helpless to effect change at Blida: Algeria’s Muslims had been subjected to what he called “absolute de-personalization,” and to remain in his position was to perpetuate a spurious normalcy. He resigned from his post in a protest letter to Resident Minister Robert Lacoste in December 1956; a month later he was expelled from Algeria. But before he left, he had a brief meeting with Abane Ramdane, an FLN leader from Kabylia who powerfully shaped his vision of the Algerian struggle. Ramdane, sometimes described as the Robespierre of the Algerian revolution, was a kindred spirit: a hardliner opposed to any negotiations prior to France’s recognition of independence, and a genuine modernizer with progressive, republican values.

After a stop in Paris — his last visit to France — Fanon settled in Tunis, where the FLN’s external leadership was based. He divided his time between the Manouba Clinic, where he resumed his psychiatric practice under the name “Dr. Fares,” and the offices of El Moudjahid, the FLN’s French-language newspaper, which he helped edit. As the FLN’s media spokesman in Tunis, he cut a glamorously enigmatic figure. Living in an independent Arab country sympathetic to Algeria’s struggle, Fanon no longer had to conceal his loyalties. Yet, paradoxically, he learned to tread even more carefully than in Blida. For all its claims to unity, the FLN was rife with factional tensions, and Fanon was a vulnerable outsider with no official position in the leadership. His most powerful ally in the movement was Ramdane, the leader of the “interior,” but Fanon was now on the other side of the border, working for the FLN’s “external” forces, who saw Ramdane as a threat to their interests.

Fanon’s contributions to El Moudjahid were not always appreciated by his colleagues in the FLN, particularly his fiery denunciation of the “beautiful souls” of the French left who denounced torture but refused to support the FLN because of its attacks on civilians. The FLN’s leaders in Tunis were pragmatic nationalists, and their goal was to intensify the divisions in France over Algeria, not condemn France as a nation. Unlike Fanon they didn’t have to prove that they were Algerians. There is no doubting the sincerity of Fanon’s writing for El Moudjahid: he tended to gravitate to the most militant positions, and he had an old account to settle with the French intelligentsia. But his fervor also expressed a longing to be accepted as a fellow Algerian. According to the historian Mohammed Harbi, a left-wing FLN official who crossed paths (and swords) with Fanon in Tunis, Fanon “had a very strong need to belong.”

Fanon upheld the FLN line even when he had very strong reasons for doubting it, as in the case of the Melouza massacre. In a small hamlet outside Melouza, the FLN had killed hundreds of sympathizers of a rival nationalist group, and then tried to blame the massacre on the French. In his first public statement in Tunis, made at a press conference in May 1957, Fanon denounced the “foul machinations over Melouza,” insisting that the French army was responsible.

He exercised a similar discretion, when, a year later, El Moudjahid announced that his friend Abane Ramdane had died “on the field of honor.” In fact, Ramdane had been dead for five months, and he was not killed on the battlefield. His erstwhile comrades had lured him to a villa in Morocco, where he was strangled to death. The external leadership had long wanted to seize control of the revolution, and Ramdane, the figurehead of the internal struggle, stood in the way. Real power now lay with the external elements of the FLN and the so-called army of the frontiers. Fanon, who was close enough to the intelligence services to know the truth of his friend’s murder, said nothing. Shaken by Ramdane’s death, he made his peace with the army of the frontiers, both for the sake of the revolution—the military leadership, in Tunisia and Morocco, was increasingly the dominant force—and to protect himself: according to Harbi, his name was on a list of those to be executed in the event of an internal challenge to the FLN leadership.

He was scarcely more secure in his medical work at the Manouba Clinic, where he began to introduce the social therapy he had practiced in Blida. The clinic’s director, Dr. Ben Soltan, called him “the Negro” and accused him of being a Zionist spy and of mistreating Arab patients on Israeli orders. The proof was his denunciation of anti-Semitism in Black Skin, White Masks, and his close friendships with two Tunisian-Jewish doctors. Dr. Fares managed to hold on to his position, but shifted his energies to the Hôpital Charles-Nicolle, where he created Africa’s first psychiatric day clinic.

He was most at ease, as ever, when he was writing—or rather, dictating. His first book on the Algerian struggle, L’An V de la révolution algérienne (translated as A Dying Colonialism), was composed over three weeks in the spring of 1959. It is a passionate account of a national awakening, as well as a document of the utopian hopes it aroused in the author, who had come to think of himself as an Algerian after three years in Blida. I don’t think it is an exaggeration to say that Fanon had fallen in love with the Algerian people. As John Edgar Wideman writes in his novel Fanon, “Fanon is not about stepping back, standing apart, analyzing and instructing others but about identifying with others, plunging into the vexing, mysterious otherness of them, taking risks of heart and mind, falling head over heels in love whether or not there’s a chance in the world love will be requited or redeemed.”

L’An V is Fanon’s love letter to the Algerian revolution, and it often feels like an expression of Ramdane’s views — or fantasies — about postindependence Algeria. In L’An V, the Algerian revolution is not simply an anticolonial uprising, but a social revolution against class oppression, religious traditionalism, and patriarchy. For all the appeals to Islam, Fanon argued, Algerian nationalism was a nationalism of the will, rather than of ethnicity or religion, open to anyone willing to join the struggle, including European democrats who renounced their colonial status and the country’s Jewish minority.

In fact, Ramdane’s vision was rapidly losing out, partly because the French army had crushed the FLN’s interior leadership during the Battle of Algiers. After independence, women in the maquis would experience a painful regression, and the pied noirs would flee en masse to France, along with Algeria’s Jews. Those who envisaged a multiethnic Algeria were always a minority, and their numbers diminished with every *pied-noir( or army atrocity. The single consensual demand inside the FLN — aside from independence itself — was the reestablishment of Algeria’s Islamic and Arab identity. Fanon was correct that France’s attempt to “emancipate” Muslim women by pressuring them to remove their veils had only made the veil more popular; what he failed (or refused) to see was that influential sectors of the nationalist movement were keen to reinforce religious conservatism. We know from a letter that Fanon wrote to a young Iranian admirer in Paris—the revolutionary Islamist Ali Shariati—that Fanon viewed the turn to Islam as a green mirage, a “withdrawal into oneself” disguised as liberation from “alienation and de-personalization.” But he shied from expressing these views in public, and leftists within the FLN were furious that Algeria’s pious bourgeoisie had, in Mohammed Harbi’s words, “found in Fanon a mouthpiece who presented its behavior as progressive.” Fanon “the Algerian” saw what he wanted to see — or what Ramdane wanted him to see. Nevertheless, he brilliantly captured the psychological impact of revolt on an oppressed people, their transformation into historical subjects. In effect, the revolution was achieving what he had hoped to do inside the walls of Blida: the “tense immobility of the dominated society,” he wrote, had given way to “awareness, movement, creation,” freeing the colonized from “that familiar tinge of resignation that specialists in underdeveloped countries describe under the heading of fatalism.” Revolution, it turned out, was the cure for the “North African syndrome.”

By the time L’An V appeared, Fanon had been pushed aside as the FLN’s media spokesman in Tunis. His replacement was the information minister of the newly formed Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA), M’hammed Yazid, a suave diplomat with strong ties to the French left, which Fanon had scornfully lectured. Fanon became a traveling ambassador and in March 1960 was appointed to Accra as the FLN’s permanent representative. The United Kingdom of Libya supplied him with a vrai faux passeport that identified him as Omar Ibrahim Fanon. He took to his new assignment with characteristic zeal.

Algeria’s liberation, he wrote in El Moudjahid, would be “an African victory,” a “step in the realization of a free and happy humanity.” Fanon saw Algeria’s war of decolonization as a model for all of Africa and first made his case — against the more conciliatory positions of his host, Ghana’s leader Kwame Nkrumah — at the 1958 All-African People’s Conference in Accra, where he led the FLN delegation and gave an electrifying speech advocating armed struggle as a uniquely effective route to national liberation. Few of Africa’s leaders were prepared to sign up. Most were cultural nationalists like Senegal’s president Léopold Senghor, who advocated African unity while accepting French interference in defense and economic policy — and siding with France at the UN against Algerian independence. Fanon was infuriated at having to argue the merits of the Algerian cause to Africans, and in one speech he nearly broke into tears.

Africa, Fanon believed, needed unyielding militants like his friend Ramdane. He was impressed by Sékou Touré, the ruthless dictator of Guinea, and once confessed that he had a “horror of weaknesses”; Touré appeared to have none. Fanon’s closest allies at the conference in Accra were Patrice Lumumba, soon to be the first prime minister of independent Congo, and Félix Moumié, a revolutionary from Cameroon. In September 1960, Lumumba was overthrown in a Belgian-sponsored coup, a prelude to his assassination. Two months later Moumié was poisoned in Geneva. “Aggressive, violent, full of anger, in love with his country, hating cowards,” Fanon wrote of his murdered friend. “Austere, hard, incorruptible.”

In November 1960, hard on the heels of Moumié’s death, Fanon undertook a daring reconnaissance mission. The aim was to open a southern front on the border with Mali, so that arms and munitions could be transported from Bamako across the Sahara. He was accompanied by an eight-man commando unit led by a man named Chawki, a major in the Algerian Army of National Liberation (ALN). They flew from Accra to Monrovia, where they planned to pick up a connecting flight to Conakry. On arriving they were told that the plane to Conakry was full and that they would have to wait for an Air France flight the following day. Suspecting a trap by French intelligence, they drove two thousand kilometers into Mali; later they learned that the plane had been diverted to Côte d’Ivoire and searched by French forces. The drive to Mali took them through tropical forest, savannah, and desert. Fanon was beguiled; in his notes on the journey, he sounds like a man possessed. “With one ear glued to the red earth you can hear very distinctly the sound of rusty chains, groans of distress,” he wrote. The gravest threat to Africa’s future, he said, was not colonialism, which was dying its inevitable death, but the “great appetites” of postcolonial elites, and their “absence of ideology.” It was his mission, Fanon believed, to “stir up the Saharan population, infiltrate to the Algerian high plateaus …. Subdue the desert, deny it, assemble Africa, create the continent.” Unlike Algeria, Africa could not create itself; it needed the help of men with energy and vision. He was calling for a revolutionary vanguard, but his rhetoric of conquest was not far from that of colonialism.

The reconnaissance mission came to nothing: the southern Sahara had never been an important combat zone for the FLN, and there was little trust between the Algerians and the desert tribes. Reading Fanon’s account, one senses that his African hallucinations were born of a growing desperation. This desperation was not only political, but physical. He had lost weight in Mali, and when he returned to Tunis in December, he was diagnosed with leukemia. Claude Lanzmann, who met him shortly after his repatriation to Tunis, remembers him as “already so suffused with death that it gave his every word the power both of prophecy and of the last words of a dying man.” Fanon pleaded with the FLN to send him back to Algeria. He wanted to die on the field of honor, and he missed the fighters of the interior, whom he described to Lanzmann as “peasant-warrior-philosophers.”

The request was denied. Still, he made himself useful to the soldiers in Tunisia. At an army post he gave lectures on the Critique of Dialectical Reason, in which he devoted special attention to Sartre’s analysis of “fraternity-terror,” the feelings of brotherhood that grow out of a shared experience of external threat. He had experienced this sort of fraternity in Blida and with Major Chawki in the desert, and he saw it again in the soldiers of the ALN. Many were from rural backgrounds, uncompromising people of the kind he trusted to maintain the integrity of the revolution throughout the Third World. It was to these soldiers that he addressed The Wretched of the Earth, dictated in haste as his condition deteriorated.

In The Wretched of the Earth Fanon characterized decolonization as an inherently violent process, a zero-sum struggle between settler and native. Albert Memmi had made a similar argument in his Portrait du Colonisé, published in 1957 with a preface by Sartre. But Fanon dramatized this struggle with unprecedented force, as an inexorable, epic battle whose outcome was not only the destruction of the Western-dominated colonial world, but the destruction of the culture and values that sustained it. The future of world history was being written in blood by the peoples without history, the “blacks, Arabs, Indians, and Asians” who had made Europe prosperous with their “sweat and corpses.” The initial stages of decolonization would be cruel and fumbling, as the colonized adopt “the primitive Manichaeism of the colonizer—Black versus White, Arab versus Infidel.” But eventually, he predicted, they would “realize … that some blacks can be whiter than the whites, and that the prospect of a national flag or independence does not automatically result in certain segments of the population giving up their privileges and their interests.” The war of national liberation, he said, must transcend “racism, hatred, resentment” and “the legitimate desire for revenge,” and evolve into a social revolution.

The arguments in The Wretched of the Earth, particularly its romantic claims about the “revolutionary spontaneity” of the peasantry, were deeply influenced by Fanon’s relationship with the ALN. The ideal of a rural utopia was, as Harbi notes, a “credo of the army,” which depicted itself as the defender of Algeria’s peasantry, and Fanon had persuaded himself that, unlike the proletariat, the peasantry were incorruptible because they had nothing to lose. In fact there was something to Fanon’s claims about Algeria’s peasantry: while the people who joined the maquis were not farmers, many of them were country people who had maintained their political and cultural traditions, and who had always regarded the French as invaders who would eventually be forced to leave. But Fanon’s depiction of the peasantry as a population uncontaminated by French culture would help to underwrite a project he had always dreaded, the nostalgic “return to the self.” Houari Boumediene, the leader of the external forces in Tunisia and later Algeria’s president, may have dismissed Fanon as “a modest man who … didn’t know the first thing about Algeria’s peasants,” but he grasped the usefulness of Fanon’s position. Like his arguments about the veil, Fanon’s celebration of peasant wisdom provided the army with — in Harbi’s words — a “rationalization of Algerian conservatism,” and a populist card to play in its power struggles with the urbane, middle-class diplomats of the GPRA, and the Marxists within the FLN.

The same was true of Fanon’s claim that violence alone would lead to victory. By the late 1950s, the FLN understood that it could never defeat the French army, and that there would eventually be a negotiated settlement. International opinion became a critical battlefield, and the principal fighters on it were representatives of the GPRA: as the historian Matthew Connelly has argued, the war was as much a “diplomatic revolution” as a military challenge. But the heroic myth of armed struggle, which Fanon did much to burnish, allowed the leaders of the ALN to present themselves, rather than the GPRA, as the real victors, and impose themselves as the country’s rightful rulers.

For all that Fanon meant his book to be a manifesto for the coming revolution, The Wretched of the Earth is perhaps most prophetic as an analysis of the potential pitfalls of decolonization. While Fanon defended anticolonial violence as a necessary response to the “exhibitionist” violence of the colonial system, he also predicted that “for many years to come we shall be bandaging the countless and sometimes indelible wounds inflicted on our people by the colonialist onslaught.” He also knew that Sartre’s “fraternity-terror” could turn inward, with lethal consequences. The idea that solidarity under arms would give way to social revolution was questionable, however. As Hannah Arendt pointed out in a perceptive critique of his work, the sense of comradeship in war “can be actualized only under conditions of immediate danger to life and limb,” and tends to wither in peacetime, as it did after independence. The taste of power that violent revolt provided was fleeting; the suffering and trauma of national liberation wars would cast a long shadow. Fanon himself had seen that anticolonial violence was driven not only by a noble desire for justice, but by darker impulses, including the dream of “becoming the persecutor.” He also predicted that leaders of postcolonial African states were sure to entrench themselves by appealing to “ultranationalism, chauvinism, and racism”: he was anticipating the Mobutus and Mugabes of the future, the “big men” who would drape themselves in African garb, promote a folkloric form of black culture, and cynically exploit the rhetoric of anticolonialism—even, in the bitterest of ironies, Fanon’s own words.

One of the earliest readers of Fanon’s manuscript was his hero, Sartre. Fanon first contacted him in the spring of 1961 through his publisher, François Maspero, to ask for a preface: “Tell him that every time I sit down at my desk, I think of him.” The admiration was mutual: to Sartre, Fanon was more than an intellectual disciple; he was the man of action Sartre never forgave himself for not having been during the Nazi Occupation. In late July 1961, they met for the first time in Rome, where they were joined by Beauvoir and Lanzmann. Their first conversation lasted from lunch until 2 a.m., when Beauvoir announced that Sartre needed a nap, much to Fanon’s irritation. Over the next few days, Fanon spoke endlessly in what Lanzmann calls a “prophetic trance.” He urged Sartre to renounce writing until Algeria was liberated. “We have rights over you,” he said. “How can you continue to live normally, to write?” He was scornful of the picturesque trattoria where they took him to eat. The pleasures of the Old World meant nothing to him.

Fanon had recently undergone treatment in the Soviet Union, where he was prescribed Myleran, and was experiencing a brief period of remission. But in Beauvoir’s account of the meeting in Rome, he comes across as a haunted man, beset by self-doubt and remorse, full of apocalyptic foreboding. The days after independence would be “terrible,” he predicted, estimating that tens of thousands would die in power struggles. The score-settling among Algerian rebels seemed to horrify him nearly as much as French repression. He blamed himself for failing to prevent the deaths of Ramdane and Lumumba, and struck Beauvoir as “upset that he wasn’t active in his native land, and even more that he wasn’t a native Algerian.” When Beauvoir shook his feverish hand, she felt as if she were “touching the passion that consumed it.”

A week after Sartre filed his preface to The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon was admitted to a hospital in Bethesda, Maryland—his only visit to the United States, a country he called “a nation of lynchers.” He was shocked, he told a friend, not that he was dying, but that he was dying in Washington of leukemia, when he “could have died in battle with the enemy three months ago.” He died on 6 December 1961, just as his book was appearing in Paris, where it was seized from bookshops by the police. In New York, Algerian diplomats gave it as a Christmas gift. Beauvoir saw his picture on the cover of Jeune Afrique, “younger, calmer than I had seen him, and very handsome. His death weighed heavily because he had charged his death with all the intensity of his life.”

Algeria achieved its independence in July 1962. It would soon become a leader of the Non-Aligned Movement, and play host to the ANC, the PLO, the Black Panthers, and other national liberation movements, many of them deeply influenced by Fanon. But over the years independent Algeria — austere, pious, socially conservative — bore less and less resemblance to the country Fanon had hoped for. Even if he had lived, it’s not clear he would have ever been at home there, any more than Che was in postrevolutionary Havana. For all that he said to Beauvoir about his desire to put down roots, Fanon was too nomadic a spirit to remain for long in any one place.

The only country that he could have called home, besides the page, was the emancipated future, a secular messianism he shared with Walter Benjamin. He worried that newly independent countries would fall into the same trap as the advanced countries of the West: the fetishism of production rates and the despoliation of the environment that Adorno and Horkheimer bemoaned in The Dialectic of Enlightenment. Fanon was not Jewish, but he had an elective affinity with the “non-Jewish Jews,” many of them Marxists, who so powerfully shaped European critical thought during the 1930s and 1940s.

In Fanon’s writing, the crimes of Nazism and imperialism are indissolubly linked: he saw colonized Algerians and Africans, like Jews, as victims of a hypocritical Europe. This linkage, which Fanon shared with Césaire in his Discourse on Colonialism, would recede with Israel’s emergence as, in Deutscher’s words, the Prussia of the Middle East, as an adversary of liberation struggles in the Third World. As the historian Enzo Traverso has argued in The End of Jewish Modernity, the “exhaustion of the Jewish cycle of critical thought” set in with Israel’s conquest of the West Bank in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, and Jewish intellectuals went from being the West’s greatest internal critics to some of its most impassioned defenders. Since then, the traditions of Jewish critical thought and postcolonialism have gone their separate ways, with notable exceptions such as Edward Said, a Palestinian literary critic steeped in the writings of Eric Auerbach and Adorno, and his friend Tony Judt, a London-born Jewish historian who became an eloquent champion of a binational state in Israel-Palestine. Fanon, in retrospect, can be seen as one of the last threads connecting these traditions, and it is striking that Arendt defended him against caricatured interpretations of his writings on violence, and never once took issue with his critique of Western imperialism. She could have done so only at the risk of contradicting her Origins of Totalitarianism.

It is no wonder, then, that one of the most striking critiques of Fanon, by turns tender and damning, should have been written by a Jewish anticolonial theorist who converted to Zionism. Albert Memmi shared much with Fanon. He was a man in-between, and never quite at home, as a Jew from Tunisia, educated in Paris, who stood between the colonizer and the colonized. He wrote novels and nonfiction, worshipped Sartre, and practiced child psychology in Tunis when Fanon was stationed there for the FLN, although the two never met. In a fascinating essay, “The Impossible Life of Frantz Fanon,” published in 1971, Memmi characterized Fanon’s life as a thwarted quest to belong. The “germ of Fanon’s tragedy,” Memmi argued, was his alienation from Martinique, his homeland. Once the dominated man recognizes that he will not be accepted by the dominant society, “he generally returns to himself, to his people, to his past, sometimes … with excessive vigor, transfiguring this people and this past to the point of creating counter-myths.” This was what Césaire had done, he suggested, by returning home from the grandes écoles of Paris, inventing Négritude, and becoming his people’s representative in the Assemblée Nationale. Fanon, however, had failed to return; instead, after realizing he could never be fully French, he transferred his fierce identification with the country that had spurned him to Algeria, the country that was battling France for its independence. Once Muslim Algeria proved too “particularist,” it was subsumed by something still larger: the African continent, the Third World, and ultimately the dream of “a totally unprecedented man, in a totally reconstructed world.”

In fact, Fanon never disavowed his Martiniquan roots, or his love of Césaire’s writing, from which he drew his images of slave revolt in The Wretched of the Earth. Even so, Memmi captures something that Fanon’s admirers in today’s antiracist movements tend to overlook: his ambivalence about his own roots, and his relentless questioning of the “return to the self.” For Memmi, a North African Jew disillusioned with Arab nationalism, identity had become destiny. And in his essay on Fanon, he wrote as if primordial ethnic identification—and the contraction of empathy it often entails—were the natural order of things, and Fanon an outlier, if not a failure, for defying it.

Fanon’s great hope was that such identification could be replaced by a new, postnational culture, a Third World humanism that the philosopher Achille Mbembe has described as “the festival of the imagination produced by struggle.” It was not to be. In much of the Third World, the dream of liberation from Europe has been supplanted by the dream of emigration to Europe, where refugees and their children now struggle for sanctuary rather than independence. Universalism, meanwhile, has turned into a debased currency: for all the talk of transnationalism, the only two postnational projects on offer are the flat world of globalization, and the Islamist tabula rasa of the Caliphate: Davos and Dabiq.

While writing this essay, I received an email from a friend, an African intellectual based in Munich. “To live in Europe today,” he wrote me, “is to wake up every day to the drum beat of naked racial hostility, with politicians and their supporters lumping us poor black souls together as the wretched and dregs of the earth, vermin for which there is no legal protection or even empathy. Everywhere one turns you are a negative, a constant subject of dehumanization and depersonalization. I am sick of the claim of a common humanity. There is no such thing as a common humanity.”

Fanon, the founding father of Third Worldism, shared my friend’s bleak view of Europe, yet he insisted that if the world was to have a future, it lay in the struggle for a common humanity. For most people, the life he chose would have been a severe test, perhaps an impossible one: in conditions of oppression and exclusion, the bonds of nation, faith, family, and clan provide sustenance, and can’t be wished away by revolutionary acts of will, as Fanon knew from his own work as a psychiatrist in Algeria. In No Name in the Street, James Baldwin writes that in all his years in Paris, he “had never been homesick for anything American,” and yet, he adds, “I missed Harlem Sunday mornings and fried chicken and biscuits, I missed the music, the style … I missed the way the dark face closes, the way dark eyes watch, and the way, when a dark face opens, a light seems to go on everywhere.” When Baldwin returned to Harlem in 1957, just as Fanon settled in Tunis, he experienced the peculiar feeling of being a stranger at home.

Fanon, who never returned home, attempted to do the opposite: to become a native in exile, in a country of the future. The emancipated future for which Fanon sacrificed his life now lies in ruins. The racial divisions, the economic inequalities, and the wars of the colonial era were not so much liquidated as reconfigured. The postcolonial world is no less divided between North and South, and no less shaped by spectacular violence, from the imperial exhibitionism of the “mother of all bombs” recently dropped in Afghanistan, to the low-tech shock and awe of throat slittings and stonings by the Islamic State. The boundaries that separate the West from the rest, and from its internal others, have been redrawn since his death, but they have not disappeared: if anything, they have multiplied. The coercive unveiling of Muslim women has reappeared in France, where burkini-clad women have been chased off beaches by police and jeering spectators. In the United States, the killings of unarmed black people by the police have furnished a grim new genre of reality television. The president has surrounded himself with white supremacists, imposed a ban on citizens from six Muslim-majority countries, and declared his intention to build a wall between the United States and Mexico, all to keep out the “bad hombres.” The era of alternative facts and hypernationalism has been a breeding ground for the racialized fears that Fanon so brilliantly diagnosed in Black Skin, White Masks. The gated enclaves, surveillance cameras, and prisons of the liberal West have created cities nearly as compartmentalized as Fanon’s Algiers. When John Edgar Wideman’s imprisoned brother asked him why he was writing a book on Fanon, Wideman replied, “Fanon because no way out of this goddam mess … and Fanon found it.” I am not sure that he did, but it was not for lack of trying, and the power of his example lies less in his answers than in his questions — questions that he was driven to ask as if by some physical necessity. How can Western democracies overcome the legacy of racial domination, so that black and brown citizens can experience the freedom enjoyed by whites? How can postcolonial societies avoid reproducing the oppressive patterns of colonial rule? What might be the shape, the identity, of a genuinely free society, an emancipated culture? As he wrote in Black Skin, White Masks, “Oh my body, make of me always a man who questions!” The mess of our postcolonial world is different from the one Fanon faced, but it is no less daunting, and finding our way out of it will require new forms of struggle, and no less imagination.

__________________________

Adam Shatz is a contributing editor at the London Review of Books. He is currently a fellow-in-residence at the New York Institute for the Humanities.

In memory of Jean Stein

Go to original – raritanquarterly.rutgers.edu

Tags: Activism, Africa, Cultural violence, Education, Geopolitics, History, Invisible violence, Literature, Politics, Racism, Social violence, Structural violence, Violence, Western World

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER:

- Wars, Trees and the Struggle for Peace

- Gandhi's Philosophy of Nonviolence: Essential Selections

- Peace in an Authoritarian International Order Versus Peace in the Liberal International Order

AFRICA:

- How the International Monetary Fund Underdevelops Africa

- How Trump’s Embrace of Afrikaner “Refugees” Became a Joke in South Africa

- New Study Reveals Changing Attitudes to Female Genital Mutilation among Sudanese Communities in Egypt

HISTORY:

- History of US-Iran Relations: From the 1953 Regime Change to Trump Strikes

- Digging Up the Roots of Human Culture

- The Geopolitics of Southeast Europe and the Importance of the Regional Geostrategic Position at the Turn of the 20th Century

LITERATURE: