Redrawing the Galtung Triangle – Finding Place for Healing Trauma in Peace Work

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER, CONFLICT RESOLUTION - MEDIATION, 17 Jun 2019

Kirthi Jayakumar – TRANSCEND Media Service

Abstract

The Galtung Triangle describes direct violence as emanating from underlying cultural and structural violence. This focal point enables a cogent understanding of how every instance of direct violence depicts something underlying that needs to be addressed. This paper digs deeper and makes the case for expanding the framework presented by Galtung, by advancing an argument that underlying structural and cultural violence, is unhealed and unresolved trauma. In doing so, this paper argues in favor of addressing the unhealed trauma in order to address both structural and systemic factors keeping violence alive, as well as the direct manifestations of violence.

Introduction

In the first classroom where I facilitated a session addressing bullying, healing underlying trauma proved to be a decisive factor in ending the ongoing, violent conflict among the students. Bullying was a serious problem in the class, with several students playing bully every now and then. But one young man constantly cornered the youngest girl in class, stealing her things, throwing her things out of the window, and shoving her against the wall whenever he got the chance. After our time together, there was a powerful transformation between these two in particular. At the end of the session, the students were invited to share their experiences and what they hoped to change about themselves. Through the process of sharing their stories, the girl who was bullied spoke about how the bully had made her feel. She shared that she was already going through a difficult time with her parents’ divorce after years of dealing with her father’s violence toward her mother and could not deal with the bullying. On listening to her, the bully marched toward her and gave her a hug before breaking down. He shared that he, too, was coping with a broken home, where his father’s violence was intolerable. With that share, the aggressive bullying ended. The two of them coached each other through their parents’ divorces and remain the best of friends today.[i]

The two traumatizing events were similar. Except, one turned aggressive and one turned meek in response. He sought to reclaim power by becoming violent. She lost her power by becoming submissive. The simple act of sharing and empathizing for each other restored peace. This lesson was my first insight into how healing and addressing trauma has tremendous value in transforming a spectrum of different kinds of violent conflict and continues to inspire my thinking even to date. From high school bullying to outright war, the different kinds of violent conflicts represent a spectrum rather than isolated blocks of conflict that mutually exclude each other.

In this paper, I will begin by exploring the impacts of trauma, specifically manifesting in the form of increasing the odds of a return to direct violence, the formation of new forms of structural violence, and the strengthening of existing forms of structural violence. I will then proceed to examine the Galtung Triangle (1969) and make the case for a “new” version of the triangle. Finally, I will argue that addressing trauma can enable conflict transformation, particularly, through transitional justice.

The Impact of Trauma

Trauma is experienced as a result of, among other things, some form of violence: be it structural, cultural, or direct (Chaitin, 2014). It can be physically, emotionally or psychologically painful, and is often experienced in a way that renders an individual powerless (Joseph, Williams, and Yule, 1997).

Violent conflict has disastrous consequences for civilians in terms of trauma: both physical and psychological (Maynard 1997; Thulesius and Hakansson, 1999). Given that civilians do not have access to their usual support systems during the subsistence of a violent conflict (Maynard, 1997): their trauma remains unaddressed. Victims of trauma “often deteriorate quickly, are socially marginalized, and struggle to contribute to their community” (Thiessen, 2013: 3).

However, beyond the consequences on the individual, trauma also has significant consequences for the community at large. As Herman (2015) explains, traumatic events impact human relationships adversely at all levels – from the personal to the communal, and beyond, to the social. She also explains that traumatic incidents “…shatter the construction of the self that is formed and sustained in relation to others… and have primary effects not only on the psychological structures of the self, but also on the systems of attachment and meaning that link an individual with her community” (Herman, 2015: 50). Thus, it can be said that societies that have not addressed collective trauma resultant from violent conflict may be vulnerable to a return to war, or some form of violence.

Several countries that have experienced violent conflict are testimony to this (Walter, 2010). Of the 103 countries that were engaged in civil war between 1945 and 2009, as many as 57% wound up relapsing into conflict, and in the process, were caught in a “conflict trap” as Collier and Sambanis (2002) called it (Walter, 2010). The problem, among a range of other factors, lies in not having completely ended prior conflicts by addressing the root cause – traumas included.

The impact of trauma on the community can be understood as one or a combination of any these consequences: an increase in the odds of a return to direct violence, the creation of new forms of structural violence, and an increased stronghold of existing forms of structural violence.

Unchecked, trauma can lead to an increase in the odds of a return to direct violence. As Maynard (1997) noted, social relationships that were once healthy and peaceful become vulnerable to chaos after, or during a violent conflict – especially because groups are positioned against each other, with distrust, fear, and anger coloring their views of each other. Many of these emotions come to fore as a result of trauma inflicted by violent conflict, and the moment there is a return to violence, these identity groups tend to become even more rigid and any potential cooperation or collaboration becomes difficult (Walter 2010). An undercurrent of unhealed trauma can be disastrous for the fabric of any society. Many of the world’s political leaders have known this, and have even used unhealed trauma to their advantage in catalyzing violence to attain goals of their own. Adolf Hitler’s choice of rhetoric and Slobodan Milosevic’s approach to reignite agony arising out of trauma culminated in horrific wars (Balke, 2002) and dangerous consequences for the populations they mobilized against, and for subsequent generations of a whole different community altogether. The Holocaust that Hitler was the mastermind of, led to negative psycho-social impacts manifesting in the form of “hostile relations between Jews and Palestinians, the Israel-Arab and Israeli-Palestinian wars, military operations and inftifadas” (Chaitin, 2014: 476).

Trauma can also lead to the development of new forms of structural violence, while perhaps also strengthening existing ones. Trauma, as Johnson (1999) explains, creates a foundation for aggression, and does so by building on the extant differences and augmenting misunderstandings among belligerent groups. In effect, unhealed and unacknowledged trauma creates room for both violent structures and cultures. Volkan (2006: 173) indicated that traumas can be “chosen, acute, or hot.” He defines chosen trauma as a group-wide and shared mental representation of historic events that caused harm, feelings of helplessness, defeat, victimization, shame, and humiliation by “others” where “drastic losses of people, land, prestige, and dignity” ensued (Volkan, 2006: 173). He explained that when such a trauma exists, the image of the “injured self” of the victim is “deposited” into the next generation, which carries on the “mourning process” in the hope of completing it (Volkan, 2006: 173-174). When the trauma is not addressed because the next generation is powerless, the trauma is transmitted to the generation that follows. Eventually, Volkan (2006) explains, this kind of a transmission winds culminates in each generation making an unconscious choice to hold onto the mental representation, which is then activated and triggered when there is a sense of danger lurking. The group, itself, for its part, continues to keep the emotional investment in the trauma alive – that is, the trauma continues to remain “hot” (Volkan, 2006). Chosen trauma operates as a means to keep victimhood alive (Volkan 2006): and structures feed on such kinds of traumas, becoming rigid when those who benefit from them find the structures under threat (Galtung, 1969).

Looking at the connection between trauma and violence through the example of Israel and Palestine, as Chaitin (2014) explained, the long-lasting traumatic effects of the Holocaust have paved the way for Israeli-Palestinian hostility, which is kept alive by structures that strengthen Israel’s military occupation of Palestine (Zertal, 2005). Chaitin (2014) calls this Israel’s chosen trauma. The support Israel derives from the United States in the international arena, its compulsory military service for its youth that draws on the traumatic memories of the Holocaust to convey a sense of urgent danger from Palestine that then encourages the youth to serve in the army, and the geographical fragmentation of Palestine that is kept in place by checkpoints (Turner, 2015) all constitute what Turner (2015) calls as Israel’s “sophisticated kinetic” efforts to keep Palestine under its occupation. Chaitin (2014) identifies al Naqba as Palestine’s chosen trauma, whose extension is the current occupation and siege of Gaza (Bar-Tal, 2013).

Trauma and Transitional Justice: Reframing the Galtung Triangle

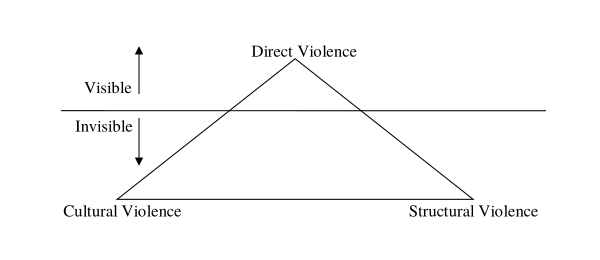

Johan Galtung’s (1969) famous ABC Triangle is explains direct violence as a manifestation of the underlying structural and cultural violence that remain hidden.

Figure 1: Galtung’s Triangle

As Zizek (2010) explains in the introduction to his book on Violence, subjective (direct) violence cannot be viewed from the same “standpoint” from which objective violence (indirect) can be viewed. Subjective violence is often seen as a “perturbation of a peaceful state of affairs” when in reality, it “explodes into visibility as a result of a complex struggle” (Zizek, 2010: 2). While both Galtung and Zizek acknowledge the undercurrents of indirect violence being the context from which direct violence emanates, they do not acknowledge that underlying all forms of violence, is an unhealed, unaddressed trauma.

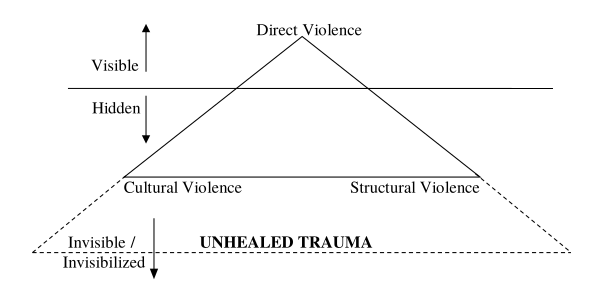

Bearing this in mind, I offer a reconstructed version of the Galtung Triangle, including trauma, which is as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Galtung’s Triangle Redrawn

In my version of the triangle, I argue that indirect violence – namely, cultural and structural violence, are hidden, rather than invisible. They produce tangible effects, and are thus tangible, though hidden. One sees structural violence prevail in institutional structures that are violent in nature, and one sees cultural violence prevail in the form of traditional and cultural views that hold a society back from a state of peace. Galtung (1990: 219-305) calls direct violence an event and designates structural violence as a process, while ascribing cultural violence the status of being invariant. He argues that the “cycle of violence” can originate from any corner, and spread to the others (Galtung, 1990: 302).

I argue that the triangle flows from bottom-up, in that though the manifestation may originate in any corner, the underlying trauma is the cause of any and all violence. This trauma is invisible – or, rather invisibilized, especially where the trauma of affected communities is not given importance when amnesty is preferred over justice.

Galtung (1990) offered an example in his seminal work on cultural violence, wherein he spoke of the evolution and trajectory of slavery. He explains that what began as a case of “massive direct violence over centuries seeps down and sediments as massive structural violence,” and “producing and reproducing massive cultural violence with racist ideas everywhere” (Galtung, 1990: 295). Over time, he argues that it is the structures and cultures that remain. This is a clear breakdown of violence as it manifests in all three forms. However, the common denominator remains unresolved trauma. The “discrimination” that Galtung argues is structural violence, and the “prejudice” he considers as constituting cultural violence are both representative of underlying unresolved trauma. Had the trauma of slavery, of death, discrimination, and deprivation faced by those who were taken as part of the slave trade been resolved, the edifice of structure (“discrimination”) and the psychological barrier of culture (“prejudice”) would no longer continue to subsist. One may want to go further into history to identify if any trauma preceded the violence of slavery itself – but that is best left to future research. Regardless, it is easy to see that this inequality and state of violence will continue until the trauma underlying it is taken seriously enough (McGrattan, 2014).

Given that violence is uniquely experienced and imbibed in terms of the effects it leaves behind in its wake, it is necessary to acknowledge that in the pursuit of transitional justice at the collective level, individual actors also need to make that transition to justice through healing. In the words of Gibney et al. (2008: 1) the “demons of the past” need to be addressed if societies want to build a better future after violent conflict. It is vital for any attempts at addressing the violence of the past to not only acknowledge the violence itself, and its impacts, but to also offer an “all-encompassing, holistic approach which will enable one to cope with the trauma in a pervasive and multidimensional manner” (Kulska, 2017: 24).

Trauma results in vivid memories of history, which includes within it a sense of victimhood that follows all forms of violence (Kulska, 2017: 25). Acknowledging, addressing, and facilitating the healing of trauma are vital components in peacebuilding and justice – be it restorative or transitional (Zehr, 2008). However, it has seldom been acknowledged thus. If trauma is not addressed or if it is suppressed, there is every chance for it to find expression in ways that can be disastrous (Kulska, 2017: 27; Brown, 2012: 446). It can prove to be a stumbling block in attaining transitional justice.

The rubric of Transitional Justice (ICTJ, 2018) comprises criminal prosecutions, truth-seeking, reparations, and a reform in the security sector. Trauma, however, does not find a mention. Inherently, transitional justice is a means for people to reconcile with the past, and to heal. However, merely recognizing this is not enough; enough means need to be dedicated toward specifically addressing trauma and healing it. Measures like the gacaca in Rwanda, the lisan in East Timor, and the Ugandan ritual of breaking the eggs (Lambourne, 2014) although in principle, offer room for such healing, often failed to follow through in the face of several challenges emanating from extending amnesty to criminals to facing reprisals for speaking up and everything else in between. The prevalence of power dynamics, as well as the lingering fear of reprisals and distrust in the system, have prevented the healing of trauma.

Within the scope the model for transitional justice as it currently exists, the inclusion of a dedicated approach to addressing and healing trauma would fill the interstice between truth-seeking and reparations – in that merely seeking the truth is not enough, but a robust and wholesome approach to operationalise that truth to help heal is vital. This implies that care must be taken to dismantle any factors that may keep the truth from coming out, and to prioritize the healing of trauma. In doing so, it is vital to acknowledge that it is not only important to acknowledge and address trauma, but to also take care to heal that trauma with due regard for the implications of such a step for the future (Kulska, 2017). Not healing or addressing trauma appropriately can have both lasting and damaging consequences that can affect society both in the present and in the future.

References:

- Balke, Edward (2002) Trauma and Conflict Prevention: A Critical Assessment of the Theoretical Foundations and Contribution of Psychosocial Projects in War-torn Societies. London: Development Studies Institute, LSE.

- Bar-Tal, Daniel (2013) Intractable conflicts: Socio-psychological foundations and dynamics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Brown, Kris (2012) ‘What It Was Like to Live Through a Day: Transitional Justice and the Memory of the Everyday in a Divided Society’, The International Journal of Transitional Justice 6(3): 444–466.

- Chaitin, Julia (2014) ‘‘I need you to listen to what happened to me’: Personal Narratives of Social Trauma in Research and Peacebuilding’, American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 84(5): 475-486

- Collier, Paul & Nicholas Sambanis (2002) ‘Understanding Civil War: A New Agenda’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 46(1): 3-12.

- Galtung, Johan (1969) ‘Violence, Peace, and Peace Research’. Journal of Peace Research 6(3): 167-191

- Galtung, Johan (1990) ‘Cultural Violence’, Journal of Peace Research 27(3): 291-305

- Gibney, Mark, Rhoda E. Howard-Hassmann, Jean-Marc Coicaud & Niklaus Steiner. (2008) The Age of Apology. Facing Up to the Past. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Herman, Judith L (2015) Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence–From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. UK: Hachette.

- International Center for Transitional Justice (2008) Transitional Justice [online] available from: <https://www.ictj.org/about/transitional-justice> [16 December 2018]

- Johnson, Nuala (1999) ‘Historical geographies of the present’. In Modern historical geographies. ed. by Graham B. and Nash C. Harlow: Prentice Hall, 251–272.

- Joseph, Stephen, Ruth Williams & William Yule (1993) ‘Changes in outlook following disaster: The preliminary development of a measure to assess positive and negative responses’. Journal of Traumatic Stress 6(2): 271-279.

- Kulska, Joanna (2017) ‘Dealing with a Trauma Burdened Past: between Remembering and Forgetting’, Polish Political Science Yearbook 46(2): 23–35

- Lambourne, Wendy (2014) ‘Transformative Justice, Reconciliation and Peacebuilding’. In Transitional Justice Theories. ed. by Buckley-Zistel, S., Beck, T. K., Braun, C., and Mieth, F. Oxon: Routledge, 19-39.

- Maynard, Kimberly (1997) ‘Rebuilding community: Psychosocial healing, reintegration, and reconciliation at the grassroots level’. In Rebuilding societies after civil war: Critical roles for international assistance. ed. Kumar, K. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 203-226.

- McGrattan, Cillian (2014) ‘Peace Building and the Politics of Responsibility: Governing Northern Ireland’ Peace and Change 39(4): 519-541

- Thiessen, Chuck (2013) ‘Community Reconciliation: The Wounds of War and the Praxis of Healing’. In Conflict, Violence, Terrorism and their Prevention. ed. by Kendall, A. J., Morrison, C., and Ramirez M.J. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing Limited, 178-192.

- Thulesius, Hans & Anders Hakansson (1999) ‘Screening for post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among Bosnian refugees’, Journal of Traumatic Stress 12(1): 167-174.

- Turner, Mandy (2015) ‘Peacebuilding as counterinsurgency in the occupied Palestinian territory’, Review of International Studies 41(1): 73–98

- Volkan, Vamik (2006) Killing in the name of identity: A study of bloody conflicts. Charlottesville, VA: Pitchstone Publishing.

- Walter, Barbara F (2010) ‘Conflict Relapse and The Sustainability of Post-Conflict Peace’, World Development Report 2011 Background Paper, Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies University of California, San Diego

- Zehr, Howard (2008) ‘Doing Justice, Healing Trauma – The Role of Restorative Justice in Peacebuilding’. Peace Prints: Southasian Journal of Peacebuilding 1(1): 1 – 16.

- Zertal, Idith. (2005) Israel’s Holocaust and the politics of nationhood. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Zizek, Slavoj (2010) Violence: Six Sideways Reflections. London: Profile Books.

NOTE:

[i] This story has been chronicled in a TEDxTalk by the author, titled “What if we teach peace, for a change?” at TEDxChennai, October 23, 2016:

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ST1ngpIWkBE

______________________________________________

Kirthi Jayakumar, from Chennai, India, b. 1987, is in the MA (Peace and Conflict Studies) program at the Center for Trust, Peace, and Security at Coventry University, UK. Kirthi is founder/chief executive officer of The Red Elephant Foundation and recipient of the US Presidential Services Medal (2012) for her services as a volunteer to Delta Women NGO, from President Barack Obama. She is the two-time recipient of the UN Online Volunteer of the Year Award (2012, 2013). Her work has been published in The Guardian and TIME Magazine. She was recognized by EuropeAid on the “200 Women in the World of Development Wall of Fame in 2016.” Kirthi received the Digital Women Award for Social Impact in 2017, from SheThePeople, Person of the Year Award, 2017 (Brew Magazine) and the Yuva Samman in 2018 (MOP Vaishnav College).

Kirthi Jayakumar, from Chennai, India, b. 1987, is in the MA (Peace and Conflict Studies) program at the Center for Trust, Peace, and Security at Coventry University, UK. Kirthi is founder/chief executive officer of The Red Elephant Foundation and recipient of the US Presidential Services Medal (2012) for her services as a volunteer to Delta Women NGO, from President Barack Obama. She is the two-time recipient of the UN Online Volunteer of the Year Award (2012, 2013). Her work has been published in The Guardian and TIME Magazine. She was recognized by EuropeAid on the “200 Women in the World of Development Wall of Fame in 2016.” Kirthi received the Digital Women Award for Social Impact in 2017, from SheThePeople, Person of the Year Award, 2017 (Brew Magazine) and the Yuva Samman in 2018 (MOP Vaishnav College).

Tags: Conflict Resolution, Johan Galtung, Nonviolence, Peace, Reconciliation, Solutions, Trauma, Violence triangle

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 17 Jun 2019.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Redrawing the Galtung Triangle – Finding Place for Healing Trauma in Peace Work, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER:

- Gandhi's Philosophy of Nonviolence: Essential Selections

- Peace in an Authoritarian International Order Versus Peace in the Liberal International Order

- Life & Teaching of Mahatma Gandhi

CONFLICT RESOLUTION - MEDIATION: