My Browser, the Spy: How Extensions Slurped Up Browsing Histories from 4M Users

MEDIA, WHISTLEBLOWING - SURVEILLANCE, TECHNOLOGY, DEVELOPMENT, 22 Jul 2019

Dan Goodin | Ars Technica – TRANSCEND Media Service

Have your tax returns, Nest videos, and medical info been made public? Don’t trust extensions.

18 Jul 2019 – When we use browsers to make medical appointments, share tax returns with accountants, or access corporate intranets, we usually trust that the pages we access will remain private. DataSpii, a newly documented privacy issue in which millions of people’s browsing histories have been collected and exposed, shows just how much about us is revealed when that assumption is turned on its head.

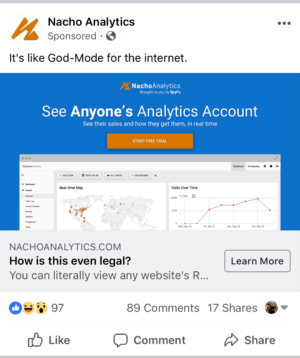

DataSpii begins with browser extensions—available mostly for Chrome but in more limited cases for Firefox as well—that, by Google’s account, had as many as 4.1 million users. These extensions collected the URLs, webpage titles, and in some cases the embedded hyperlinks of every page that the browser user visited. Most of these collected Web histories were then published by a fee-based service called Nacho Analytics, which markets itself as “God mode for the Internet” and uses the tag line “See Anyone’s Analytics Account.”

Web histories may not sound especially sensitive, but a subset of the published links led to pages that are not protected by passwords—but only by a hard-to-guess sequence of characters (called tokens) included in the URL. Thus, the published links could allow viewers to access the content at these pages. (Security practitioners have long discouraged the publishing of sensitive information on pages that aren’t password protected, but the practice remains widespread.)

According to the researcher who discovered and extensively documented the problem, this non-stop flow of sensitive data over the past seven months has resulted in the publication of links to:

- Home and business surveillance videos hosted on Nest and other security services

- Tax returns, billing invoices, business documents, and presentation slides posted to, or hosted on, Microsoft OneDrive, Intuit.com, and other online services

- Vehicle identification numbers of recently bought automobiles, along with the names and addresses of the buyers

- Patient names, the doctors they visited, and other details listed by DrChrono, a patient care cloud platform that contracts with medical services

- Travel itineraries hosted on Priceline, Booking.com, and airline websites

- Facebook Messenger attachments and Facebook photos, even when the photos were set to be private.

In other cases, the published URLs wouldn’t open a page unless the person following them supplied an account password or had access to the private network that hosted the content. But even in these cases, the combination of the full URL and the corresponding page name sometimes divulged sensitive internal information. DataSpii is known to have affected 50 companies, but that number was limited only by the time and money required to find more. Examples include:

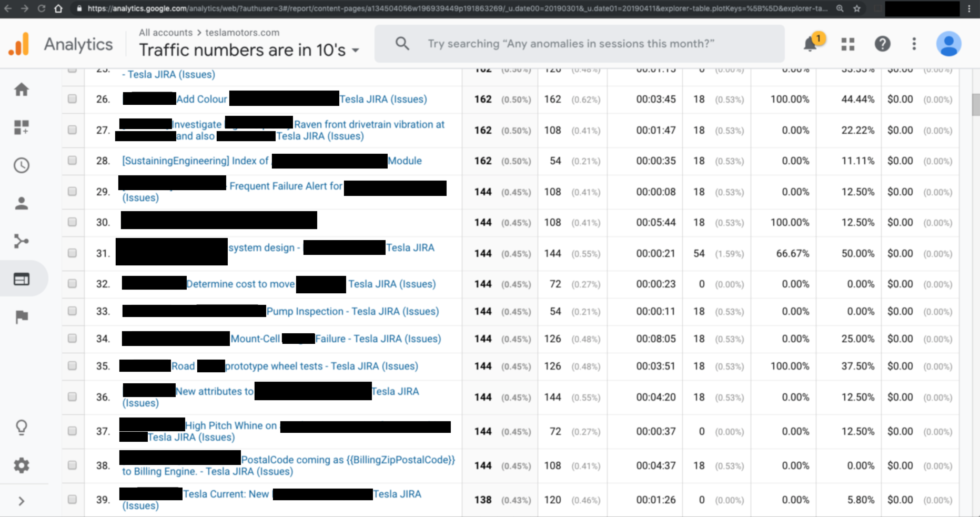

- URLs referencing teslamotors.com subdomains that aren’t reachable by the outside Internet. When combined with corresponding page titles, these URLs showed employees troubleshooting a “pump motorstall fault,” a “Raven front Drivetrain vibration,” and other problems. Sometimes, the URLs or page titles included vehicle identification numbers of specific cars that were experiencing issues—or they discussed Tesla products or features that had not yet been made public. (See image below)

- Internal URLs for pharmaceutical companies Amgen, Merck, Pfizer, and Roche; health providers AthenaHealth and Epic Systems; and security companies FireEye, Symantec, Palo Alto Networks, and Trend Micro. Like the internal URLs for Tesla, these links routinely revealed internal development or product details. A page title captured from an Apple subdomain read: “Issue where [REDACTED] and [REDACTED] field are getting updated in response of story and collection update APIs by [REDACTED]”

- URLs for JIRA, a project management service provided by Atlassian, that showed Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos’ aerospace manufacturer and sub-orbital spaceflight services company, discussing a competitor and the failure of speed sensors, calibration equipment, and manifolds. Other JIRA customers exposed included security company FireEye, BuzzFeed, NBCdigital, AlienVault, CardinalHealth, TMobile, Reddit, and UnderArmour.

Clearly, this is not good. But how did it happen?

The Data Spy:

TO CONTINUE READING Go to Original – arstechnica.com

Tags: Big Brother, Fraud, Google, Media, Spying, Surveillance, Technology

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

MEDIA:

- The Media Calls Israeli Captives “Hostages” and Palestinians “Prisoners”

- The Media Navigator (2025)

- Zuckerberg and Musk Have Shown that Big Tech Doesn’t Care about Facts

WHISTLEBLOWING - SURVEILLANCE:

- I’ve Worked at Google for Decades and I’m Sickened by What It’s Doing

- Julian Assange and the Criminalization of Journalism: A Story of Moral Injury and Moral Courage

- Why the US Let Assange Go

TECHNOLOGY:

- Software Developers in Oakland Are Putting People Over Profit

- Weaponizing Reality: The Dawn of Neurowarfare

- Israeli Intelligence to Be Granted Full Access to National Biometric Database

DEVELOPMENT: