The Colombian Protests Reflect a Deep Legitimacy Crisis

LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN, 24 May 2021

The country could slip into another cycle of violence if the government continues to ignore people’s grievances.

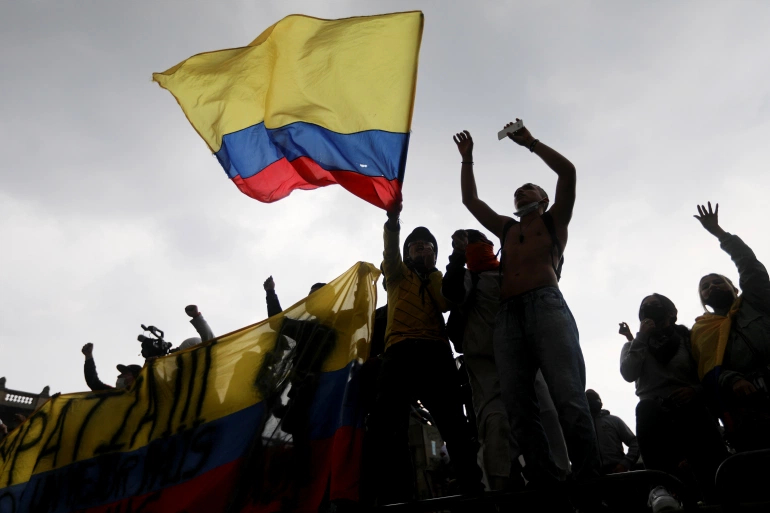

Demonstrators take part in a protest against the tax reform of President Ivan Duque’s government in Bogota, Colombia on May 1, 2021.

[Reuters/Luisa Gonzalez]

22 May 2021 – On April 28, protests erupted across Colombia after the right-wing government of Ivan Duque proposed increasing taxes amid the third wave of the coronavirus pandemic. Although the president withdrew the contentious tax reform proposal in the face of public anger, demonstrations have persisted, aggravated by a brutal crackdown.

At least 40 protesters have been killed and hundreds injured by security forces and armed men dressed in civilian clothes. Many have been arrested and dozens of women have been sexually assaulted by police officers.

The escalation of violence reflects not only the failure of the government to address longstanding socioeconomic grievances but also its increasing loss of legitimacy and retreat of democracy. This is putting the country at risk of slipping back into conflict.

The trigger: Unfair tax reform

The Colombian government initially advertised the tax reform it proposed as a measure aimed at collecting revenue to roll out a “solidarity income” scheme to help those Colombians most hard-hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. But the way the reform package was formulated made it clear that it was going to do more damage than good for the poor and vulnerable.

While the reform package included a wealth tax for individuals with assets above $1.35m, it also had many provisions that would have hurt low-income households. It would have lowered the taxable income threshold and increased pension and value-added tax (VAT), which would have significantly increased the prices of subsistence items, such as eggs, milk, cheese and meat.

Other elements of the reform benefitted the private sector and specific economic groups. They included maintaining several tax exemptions for various industries, including the finance sector, mostly benefitting well-off entrepreneurs.

While the government was claiming the tax reform was necessary to help mitigate the effects of the pandemic on the Colombian economy and state budget, it was also pushing for some questionable spending, including on expensive arms purchases from the United States.

Although some of the reform elements could have had positive effects on the economy, such as tax breaks for vulnerable sectors, the increase in VAT indicated a disconnect between the ruling elites and the lived experiences of vast segments of the population.

It is estimated that 3.5 million people have fallen into poverty due to the COVID-19 pandemic, bringing the number of those living in poverty from 17.5 million in 2019 to 21 million (42.5 percent of the population) in 2020. The crisis has severely hit those employed in the informal sector who constitute half of the labour force. They would not have benefitted from any tax refunds that formal labourers would have enjoyed as compensation for the increase in VAT.

The government’s response: Violence and slander

The initial response of the government to cross-sector criticism of its tax reform proposal was completely tone-deaf. Finance Minister Alberto Carrasquilla addressed the media, trying to defend the package, but ended up revealing that he had no idea how much basic staples cost. Speaking on the effect of the VAT extension, he claimed eggs cost a quarter of what they actually do on the market, triggering more public anger.

When protests started, instead of engaging in open dialogue and listening to the population’s grievances, the government resorted to a smear campaign. It tried to portray the demonstrations as a radical left-wing conspiracy that was going to destabilise the country.

Several pro-government figures have publicly accused the protest organisers of trying to establish a “castrochavismo” regime in Colombia. Such conspiracy theories have been mainstreamed in some sectors of the armed forces and the police which genuinely believe protesters are aiming to overthrow the state to advance a left-wing revolution.

Weaponising these narratives, the government went further and ordered the crackdown on protesters, deploying security forces and the military, which rolled out tanks and used violence to disperse the unarmed, mostly peaceful crowds.

Even when the United Nations and human rights organisations condemned the violence, the government failed to respond and rein in the security forces. Its disregard for the grievances of various sectors of the population, and even their lives, has brought popular mobilisation to a level not seen in decades.

Mobilisation as an outcome of the 2016 peace accords

While the proposed tax reform was the trigger of the recent protests and the government’s violent response – its fuel, the social roots of the general discontent go much deeper than that.

For years, governments have failed to address the growing inequality in Colombian society, as poverty reduction efforts have stagnated. Under the influence of Colombia’s wealthy class, they have repeatedly made policy decisions that have made citizens more vulnerable and more distrustful of the state.

But the protests should also be seen in the context of the 2016 peace agreements between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP), which put an end to the five-decade-long conflict between them.

As the violence between the FARC-EP and the government declined, social movements gained more space for mobilisation. The peace agreements also created the expectations that after the end of this armed conflict, the government would become more responsive to its citizens’ grievances.

Even after the peace agreement, however, violence against civilians continued. Indigenous leaders, social activists, human rights defenders, peasants and environmentalists, who have defended various communities’ rights and worked on implementing the provisions of the 2016 peace accords, have been assassinated. The government has taken no serious action to stem the continuing violence or to hold accountable members of the security forces or non-state actors, such as cartels, left-wing and right-wing armed groups, who are still victimising Colombian civilians.

Meanwhile, much of the political elite continues to perceive demands for democratic reform as left-wing conspiracies to overthrow the state.

A legitimacy crisis

The protests of the past few weeks, while triggered by various socioeconomic grievances and fuelled by the government’s violent response, also evince the continued absence of adequate channels through which citizens can hold their government accountable.

It seems that the ruling elites expect from the general population silent acquiescence to whatever policies they choose to pursue. The narrative they use in the face of popular mobilisation focuses on “re-establishing order”, which means ensuring submission by employing brutal force.

But the idea that state legitimacy derives from the monopoly of force is an obsolete one. The ruling elites’ embrace of coercion is part of a dangerous trend towards the erosion of participatory democracy across Latin America and beyond.

Colombia is a country in which the political leadership has historically feared mobilisation, even when done peacefully. Such fears have led to the closure of avenues for political representation and participation. They have fuelled cycles of violence, including the armed conflict with FARC, from which the country is still recovering.

The current government is repeating past mistakes by smearing protesters and ordering the violent dispersal of demonstrations. It is also failing to implement the 2016 peace accords.

The loss of legitimacy carries high risks for Colombia. It is reflected in the escalation of violence against police forces, which has the dangerous potential of encouraging civilians to join armed groups still active in the country. This, in turn, could be used by the ruling elite to restart the counterinsurgency efforts and shut down democratic channels of participation and representation, as it has done in the past.

The current events place Colombia at a crossroads. Should the government choose to recognise the grievances of the population and engage in dialogue, it can help the state regain legitimacy and work towards strengthening the social contract. Should it choose to continue the militarisation of cities and its disregard for the needs of the population, it should prepare for more unrest and international pressure to change course before the country descends into another conflict.

______________________________________________

Fabio Andrés Díaz Pabón is a researcher at the African Centre of Excellence for Inequality Research (ACEIR) at the University of Cape Town and a research Associate at the Department of Political and International Studies at Rhodes University.

Fabio Andrés Díaz Pabón is a researcher at the African Centre of Excellence for Inequality Research (ACEIR) at the University of Cape Town and a research Associate at the Department of Political and International Studies at Rhodes University.

Maria Gabriela Palacio is an assistant professor at the institute for history in the Faculty of Humanities at Leiden University. Her research contributes to interdisciplinary work on development studies, with a focus on social policy.

Go to Original – aljazeera.com

Tags: Colombia, Conflict, Crisis, Economic Crisis, Latin America Caribbean

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN: