The Targeted Death and Extinction of Muslin by British Imperialism

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 13 Jun 2022

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

“The Englishman flourishes, and acts like a sponge, drawing up riches from the banks of the Ganges, and squeezing them down upon the banks of the Thames.”

— John Sullivan 1840 [1]

An Indian model draping an angelic, Bengali muslin stole from the 19th century, India. (Credit Drik Bengal Muslin)

200 years ago, Dhaka muslin, woven by indigenous peoples of India on hand looms was the most valuable and sought-after fabric on earth. It was the latest fashion trend in Europe, at the time. Then it was totally annihilated. The question as to how did this beautiful fabric become extinct needs to be raised and how can this traditional weaving of the “Fabric of Gods” be resurrected in modern times?[2] The finest fabric in human history was perfected by the Bengali people but tragically lost in the wake of British imperialism and strategically planned economic ruin of India, during its 200-year history of occupation and plunder by military forces of oppressive white Britain.[3]

Muslin was once called “The vapor of dawn” by a Chinese trader named Yuan Chwang[4]. Other names were “woven wind” and “wonder gossamer” . However, presently, the younger generation has not heard of muslin and fashion houses of Europe have simply abandoned it from the repertoire pf fabrics used in the divine creations of female haute couture[5] attire to adorn the figures of divinely created model bodies which walk the ramps of American and European fashion shows. Muslin is now identified with Regency period dramas created by the likes of Ismail Merchant[6] film producers. Haute couture can be referenced back as early as the 17th century.[7] Rose Bertin, the French fashion designer to Queen Marie Antoinette, can be credited for bringing fashion and haute couture to French culture.[8] Visitors to Paris brought back clothing that was then copied by local dressmakers. Stylish women also ordered dresses in the latest Parisian fashion, to serve as models.

In late 18th Century Europe, a new fashion led to an international scandal. In fact, an entire social class was accused of appearing in public, naked. The culprit was Dhaka muslin, a precious fabric imported from the city of Dhaka, in east India, in what is now Bangladesh, then in Bengal. It was not like the cheap muslin in the present-day fabric market, where it is used to prepare prototypes of new styles, in fashion houses, obviating the use of expensive fabrics. This Dhaka muslin was manufactured in an elaborate, 16-step process with a rare cotton that only grew along the banks of the holy Meghna River[9], which is one of the major rivers in Bangladesh,[10] one of the three that form the Ganges Delta, the largest delta on earth, which fans out to the Bay of Bengal. The muslin cloth itself was considered one of the great treasures of the era. It had a global demand and a historical lineage, stretching into ancient history, of many millennia. The cloth was deemed worthy of clothing statues of goddesses in ancient Greece, countless emperors from Persian, China and Western Europe to other distant kingdoms of western Siberia in distant lands, as well as generations of the Mughal dynasty in India.

There were many different types of muslin fabric, but the finest were honoured with evocative names conjured up by imperial poets, such as “baft-hawa”, literally “woven air”. These high-end muslins were said to be as light and soft as the wind. According to one traveler, to India, they were so fluid you could pull a bolt, a length of 91metres, through the centre of a ring. Another wrote that you could fit a piece of 18 metres, into a pocket snuff box.[11] Essentially, Dhaka muslin was also more than a little transparent, in nature. While traditionally, these premium fabrics were used to make saris and jamas, which are tunic-like garments worn by men, in the Victorian United Kingdom, they transformed the style of the aristocracy, extinguishing the highly structured dresses of the Georgian era. Five-foot horizontal waistlines that could barely fit through doorways were out, and delicate, straight-up-and-down “chemise gowns” were in. Not only were these endowed with a racy gauzy quality, they were in the style of what was previously considered underwear.

Muslin between the 16th and 18th centuries, did not only adorn the bodies of aristocratic ladies but even the mighty Mughal Emperors wore dresses made of Dhaka muslin, and this became another crucial signifier of its quality. In the Mughal scheme of things, all authority and power was vested in the emperor, who manifested a God-given “radiance.” The display of pomp and the magnificence of the imperial lifestyle, therefore, was not merely personal gratification as much as it was political expression, an essential display of the empire’s grandeur. Muslin, by being worn by the emperor, became a part of the Mughal apparatus of power. [12]

Few dynasties in the world have had the artistic and cultural attributes of the Mughal emperors, which they displayed in remarkably integrated forms of architecture, literature, gardens, painting, calligraphy, vast imperial libraries, public ceremonies and carpets. The Mughals often embellished their muslin-wear with Persian-derived motifs called butta[13] and embroidery known as chikankari[14]. More crucially, they incorporated it within their aesthetic framework, giving names that drew on the idioms and images of classical Persian poetry for the different varieties of muslin: abrawan (flowing water); shabnam (evening dew); tanzeb (ornament of the body); nayansukh (pleasing to the eye); and more. Although Bengal was ruled by Muslims from the 13th century onwards, it was Emperor Akbar’s [15] General Islam Khan [16]who re-cast Dhaka as Bengal’s capital, giving it distinct Mughal contours. It was during Akbar’s half century of reign in the late 16th century that mulmul khas (“special clothing,” or muslin diaphanously fine) began to be made exclusively for the emperor and the imperial household. It was Akbar again who deemed muslin suitable for India’s summers and who designed the Mughal jama, men’s outerwear with fitted top and a pleated skirt falling to below the knees.

There are many stories about the translucent quality of the mulmul khas. One of the most enduring is that of Emperor Aurangzeb [17]chiding his daughter Princess Zebunnisa[18], a poet well-versed in astronomy, mathematics and Islamic theology, for appearing in transparent dress in court. She replied, to the astonishment of her father, that her dress, in fact, consisted of seven separate layers of muslin.

All this ancient, prized muslin was woven on the Indian pit treadle loom, one that has remained relatively unchanged over roughly 4,000 years. It was made of bamboo and rope, at which the weaver sat with his feet in a pit dug below to operate the treadles. It was amazing that this rudimentary construction had snared whole empires in its almost invisible threads. Weaving is as old as Bengal, conspicuously present in its oldest literature. In the Charyapadas of the 10th century,[19] written on palm leaves in the oldest form of the Bengali language yet known, the loom, yarn and weaving represent mystical concepts. Weavers populate the Mangalkavyas[20] written by medieval Bengali poets; they are also present in older ballads, chants and songs as well as depicted in terra-cotta. The question which is often raised is that how did they make a storied cloth that, when wet with evening dew, became invisible against the grass below? German scholar Annemarie Schimmel [21]put it well when she wrote of their “unsurpassed ability to create amazing works of art with tools which appear extremely primitive today. Who today could weave the fabric described as ‘woven air’?”

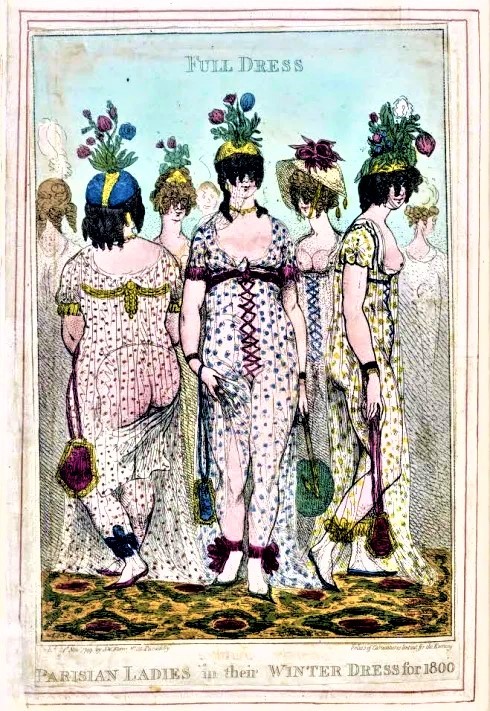

In one popular satirical print by Isaac Cruikshank[22], a clique of women appear together in long, brightly coloured muslin dresses, through which you can clearly see their bottoms, nipples and pubic hair.

Meanwhile in an equally misogynistic comedic excerpt from an English women’s monthly magazine, a tailor helps a female client to achieve the latest fashion. “Madame, ’tis done in a moment,” he assures her, then instructs her to remove her petticoat, then her pockets, then her corset and finally her sleeves “‘Tis an easy matter, you see,” he explains. “To be dressed in the fashion, you have only to undress.”

Still, Dhaka muslin was a fashion statement, with those who could afford it. It was the most expensive fabric of the era, with a retinue of dedicated fans which included the French queen Marie Antoinette, the French Empress Joséphine Bonaparte and Jane Austen. But as quickly as this wonder-cloth struck enlightenment in Europe, it vanished. Like the head of Marie Antoinette[23]. The head of Marie Antoinette, desired by the leaders of the French Revolution, was cut off cleanly at 12:15 on Wednesday, 16th October 1793, and was exhibited to a joyous public. On the very day of the execution, the Queen’s mutilated body was taken to the small cemetery of the Madeleine, where the King’s body had been left nine months earlier.

At its peak, muslin was on display at the French court where, at the close of the 18th century, Empress Josephine’s muslin dresses set the course for the Empire Line style in France and later in Regency-era Britain. That style centered around muslin, since only “filmy muslin,” wrote Christine Kortsch[24], author of Dress Culture in Late Victorian Women’s Fiction, “clung Greek-like to the body and no color would do but white.”

In the Bangla language, a place where muslin was made and sold was called Arong, and the largest Arong was at Panam Nagar, in Sonargaon, where the East India Company factory was located. It now stands as a reminder of how what was once the cloth of emperors was felled by an industrialising, colonial British economy.

But muslin’s days were numbered. The British colonial apparatus, whether in the form of the East India Company or as direct rule by the Crown, was a vast extractive machine. So too had been the Mughal state, which had herded the weavers into designated workshops called kothis to labor in harsh, even punitive, conditions. But compared to the pitiless operations of the British, the Mughals were models of mercy. On one side, both Company and Crown squeezed the farmers and the weavers until nothing was left, then squeezed some more. On the other, a factory-produced, mass-product “muslin” rolled off the newly invented power looms in Lancashire cotton mills during the Industrial Revolution in England[25]. Aided by a raft of tariffs, duties and taxes, British cotton textiles flooded not only the European markets, but the Indian ones as well, bringing Bengal’s handloom cotton industry, and muslin, to its knees.

Along the riverbanks, phuti karpas became extinct. Famines swept through the previously fertile land of Bengal, and spinners and weavers changed occupations, fled from their villages or starved. Only jamdani, known as “figured muslin”[26] due to the flower and abstract motifs woven on it, survived to the present times.

In an excellent publication by Nitin Singh and Nikhil Venkatesa[27] “5 Ways Imperial Britain Crippled Indian Handlooms” they critically analyse the strategies used by the British Raj to cause a “Traditional Arts and Crafts Genocide” in India. The British could not see a vibrant nation, they colonised, raped, oppressed and killed, could flourishes in global trade and culture, The British Empire cunningly invades on the pretext of trade, takes over the nation, holds them in bondage for two centuries, until a grassroots movement rises to remove the imperialists and claim what is rightfully theirs. It is the story of India, as of all other countries they occupied and subjugated the indigenous people therein. In India they achieved this meticulously by destroying the local industries to assert imperial dominance. That included India’s handloom textile industry, which was manufacturing 25% of the world’s textiles in the 17th century, and that this share plummeted to just 2% at the end of British colonialism in 1947 as documented by Das 2002[28] and others.[29]

How exactly did Britain do it? Some of the strategies they used were brute force methods that were enforced by their military presence in the region, others were shrewd economic moves that automatically took their toll. The five methods which imperial Britain used to permanently cripple the Indian handloom industry are as follows:-

- Price fixing and buyer monopolies “..the Company fixed the prices of textiles so low that weavers could hardly redeem 80% of their cost of production.” In 1612, the British established two trading stations in Surat and Masulipatnam, both bustling port towns of India. This was the Company’s first step towards monopolising the textile trade after the Dutch did the same with spices in Indonesia.

- Brute force, violence, and imprisonment

- Taxes, taxes, taxes

- Industrial Revolution and innovation

- Strategic theft of Intellectual Property. India’s Mughal Era gave birth to a distinct style of textile motifs that were drawn from the Persian heritage of its rulers. These motifs enriched the Indian design vocabulary and invited further interest from foreign buyers, but Britain soon swept these designs clean, making only a few key adjustments for their own gains. Irwin (1919)[30] describes how the British perceived Indian designs as ‘dark designs done on sad red backgrounds’ and instead modified these designs by painting these coloured patterns on white/off-white bases to make them more suitable for the tastes of European consumers.

With these five strategies, price fixing, violence, taxes, innovation, and strategic theft, Britain crippled India’s handloom industry. It is also evident which factors were conducive to driving demand away from handlooms in the 18th and 19th centuries; sustainability and heritage were not factors which buyers kept in mind when considering what clothing to purchase, yet, these are factors which matter to the modern consumer. As long as the global community can keep demand growing steadily by creating designs which speak to the present, while echoing the past, perhaps the handloom industry can be afforded a chance to return to their former glory, in the future.

” Resurrected Phuti karpas cotton plants look identical to the kind used to grow Dhaka muslin in the 17th century (Credit: Drik/ Bengal Muslin)

Gossypium arboreum, commonly called tree cotton.[31] Phuti karpas[32] is a species of cotton native to India, Pakistan and Bangladesh and other tropical and subtropical regions of the Old World.

The Bottom Line is Gossypium arboreum var. neglecta, locally known as “Phuti karpas”, was the variant used to make Dhaka muslin in East India, now Bangladesh.[33] The variant could only be grown in an area south of Dhaka, along the banks of the Meghna River. It could be spun so that individual threads could maintain tensile strength at counts higher than any other variant of cotton.[34] Although muslin weaving is nearly non-existent today, pit-loom workshops such as this one in Sonargaon, near Dhaka, continue to produce jamdani saris, which most likely take their name from Persian words meaning a vase of flowers. Delicate yet far less fine than true muslin, jamdani is made by weavers who have kept alive the tradition of “fine” weaving in Bangladesh.[35] Yet as one weaver pointed out wryly, he could earn twice as much in a factory, so “being a weaver makes little sense. It’s more a habit than a profession.”

Ironically, weavers and spinners, the women and men behind the magic fabric are all gone, due to the stringent oppression of the muslin industry during the British Raj in India. However, the faces of rural Bengal, the sunburnt, lean, teeth stained with paan,[36] (beetle leaf), remain as ghost memories for the live elders of the industry, minimal in members, about to become totally extinct, taking away the hereditary secrets of the making of the best muslin in the world, with them forever. Their task at the time was impossibly backbreaking, mind-numbing labor, supported by large groups of farmers, washers, cleaners, dyers, sewers, embroiderers and balers, all organised, in typically Indian fashion, by religion and caste, all destroyed by British imperialists not only in a racial, religious, traditional cultural genocides, but also a total annihilation of the thousands of years old home industry of fine muslin weaving, never to be rekindled to its original glamour and standards. The holy Meghna River is severely polluted with industrial, toxic wastes, to such an extent that not only does Phuti karpas does grow on its banks, anymore, but no edible and other plants do. The traditional skills are all dead with the muslin fraternity, as well as the international demand for the fabric, which is replaced by synthetic, mass produced fabrics. The death knell was initiated by the the occupying forces of colonial Britain, it is to be remembered.

However, there is a ray of hope for the resurrection of the muslin industry, in places like Pakistan and even Bangladesh as well as in India, where the art of muslin weaving is being retaught and traditional production technologies, of ancient fabrics such as bamboo fabrics of feudal China and Japan are being rekindled, in the 21st century, more as an art form rather than as a global industry, muslin was in a bygone era.

References:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Sullivan_%28colonial_administrator%29

[2] https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20210316-the-legendary-fabric-that-no-one-knows-how-to-make#:~:text=Nearly%20200%20years%20ago%2C%20Dhaka%20muslin%20was%20the%20most%20valuable%20fabric%20on%20the%20planet.%20Then%20it%20was%20lost%20altogether.%20How%20did%20this%20happen%3F%20And%20can%20we%20bring%20it%20back%3F

[3] https://www.nataniabarron.com/2021/03/22/muslin-and-the-lost-traditions-of-bangladesh/

[4] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=5b85c4b86b8888f8148b0ca2d41c5da70ff2f808bd5234b385bbc8b3f7594030JmltdHM9MTY1NDY3NzI1NiZpZ3VpZD0yOGRkNzI1OS1iZDQ4LTQ5MWItODRkNi00YjA0NjkyYzI1OGQmaW5zaWQ9NTE2Mg&ptn=3&fclid=c81d596a-e705-11ec-b466-4e67b19e7450&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZXhhbXlhdHJhLmNvbS9hbmNpZW50LWhpc3RvcnktMjAwMC0yMDE4LXBhcnQtMS8x&ntb=1

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haute_couture#History_in_France

[6] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=6287086e1af0681c94b588ab3f96d4dcb0467edf12ce4bc45a80b4f969f86e28JmltdHM9MTY1NDY3NjQ5OCZpZ3VpZD0xYjI2Y2Y2ZC1mOWRjLTQ5YmMtOWNiNC05Mjc0ZWE1OGIwZTImaW5zaWQ9NTM5Nw&ptn=3&fclid=041c8ed2-e704-11ec-bc34-40ede910f612&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvTWVyY2hhbnRfSXZvcnlfUHJvZHVjdGlvbnMjOn46dGV4dD1NZXJjaGFudCUyMEl2b3J5JTIwUHJvZHVjdGlvbnMlMjBpcyUyMGElMjBmaWxtJTIwY29tcGFueSUyMGZvdW5kZWQsRHVyaW5nJTIwdGhlaXIlMjB0aW1lJTIwdG9nZXRoZXIlMkMlMjB0aGV5JTIwbWFkZSUyMDQ0JTIwZmlsbXMu&ntb=1

[7] Steele, Valerie, ed. (2010). The Berg Companion to Fashion. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 393. ISBN 978-1-8478-8563-0.

[8] Nudelman, Zoya (2009). The Art of Couture Sewing. London: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-5636-7539-3.

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meghna_River

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meghna_River#:~:text=Masud%20Hasan%20Chowdhury%20(2012).%20%22Meghna%20River%22.%20In%20Sirajul%20Islam%20and%20Ahmed%20A.%20Jamal%20(ed.).%20Banglapedia%3A%20National%20Encyclopedia%20of%20Bangladesh%20(Second%C2%A0ed.).%20Asiatic%20Society%20of%20Bangladesh.%20Retrieved

[11] https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20210316-the-legendary-fabric-that-no-one-knows-how-to-make#:~:text=According%20to%20one%20traveller%2C%20they%20were%20so%20fluid%20you%20could%20pull%20a%20bolt%20%E2%80%93%20a%20length%20of%20300ft%2C%20or%2091m%20%E2%80%93%20through%20the%20centre%20of%20a%20ring.%20Another%20wrote%20that%20you%20could%20fit%20a%20piece%20of%2060ft%2C%20or%2018m%2C%20into%20a%20pocket%20snuff%20box.

[12] https://www.aramcoworld.com/Articles/May-2016/Our-Story-of-Dhaka-Muslin

[13] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=c91eb84d78eb9a669393d35ff6030dad8b67799b597e6699d685e24065b90f06JmltdHM9MTY1NDkzNjY0NSZpZ3VpZD1mZWIyNmYwMS01NmVkLTRhMzMtYTg4OS1iODUyNzhiYzY4YzkmaW5zaWQ9NTE2Mw&ptn=3&fclid=b8312269-e961-11ec-bde1-452d1b2c7211&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvUGFpc2xleV8oZGVzaWduKQ&ntb=1

[14] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=720ad059411f57b6f9cc320deeea4496fc5bffcf52ed307f6afd479a4b6c6fedJmltdHM9MTY1NDkzNjgzNyZpZ3VpZD02MGY0NTM2Yi1lMDVhLTRhMGItYWQ5Yi02OGExZmI5OTNkZjMmaW5zaWQ9NTM5Ng&ptn=3&fclid=2a56c1f7-e962-11ec-b00b-63a52ae48064&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cud2VkZGluZ3dpcmUuaW4vd2VkZGluZy10aXBzL2NoaWthbmthcmktZW1icm9pZGVyeS0tYzc0MjkjOn46dGV4dD0lRTIlODAlOThDaGlrYW5rYWFyaSVFMiU4MCU5OSUyMG1lYW5zJTIwdGhlJTIwYXJ0JTIwb2YlMjAlRTIlODAlOThjaGlrYW4lRTIlODAlOTklMkMlMjB0aGUlMjB0ZXJtLHRoZSUyMGZpbmUlMjB3aGl0ZSUyMHRocmVhZHMlMjB0byUyMHBpZXJjZSUyMHRocm91Z2glMjBpdC4&ntb=1

[15] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=97a073440c24c3d9b97f90ead60e7da65c4f86f8419dcfdc60ed145e7116e03dJmltdHM9MTY1NDkzNzAyMyZpZ3VpZD0yZmE3ZGYzNy1lOTg2LTRkOGItYTljNy02YmY1ZDQwMjNmZWQmaW5zaWQ9NTE3NQ&ptn=3&fclid=997a484f-e962-11ec-9093-111fa21a8d32&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvQWtiYXI&ntb=1

[16] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=79a7308f041e36e4a95e4970f4205dc20d3a2cb1926245a0249e740bb3ec747bJmltdHM9MTY1NDkzNzE4MCZpZ3VpZD0wNWIyYWE4OS0yMTYxLTQwMGMtOTUwZi04ZmY1MTMwYTE1NGMmaW5zaWQ9NTE1OQ&ptn=3&fclid=f6e20f34-e962-11ec-be4d-0feed35374a4&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvSXNsYW1fS2hhbl9J&ntb=1

[17] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=9f4ba4373b5464317b93e60ca5ab1fe45fcb9e9fb52ebade433e37653131a0c9JmltdHM9MTY1NDkzNzM1MSZpZ3VpZD01YjZjYzljZS02ZDVmLTQ1ZDAtODhjNS1kNGY3NGUyYWVmMmEmaW5zaWQ9NTE4MQ&ptn=3&fclid=5ca88133-e963-11ec-a45a-1dc1f87dc6fe&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvQXVyYW5nemVi&ntb=1

[18] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=709246d069041360805cd8fcf9091c20aaa5e82d6170f36d40ce171d79d1c462JmltdHM9MTY1NDkzNzgyOSZpZ3VpZD0xODFiM2Q2Ni1mYTczLTRlY2MtYmFkZC1lYjA5ZjMyZDE3Y2YmaW5zaWQ9NTE1Mw&ptn=3&fclid=79f89d6f-e964-11ec-8076-deeac8a090e3&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvWmViLXVuLU5pc3Nh&ntb=1

[19] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=f787ed6cbc51d7060f941ce2902bbc1957b430524137f849546f8fb263bc1982JmltdHM9MTY1NDkzODE3NSZpZ3VpZD04MmM0NDBjZi01MjJhLTQyYmItYjI1OC1kOTc1MzlmMTJkZjImaW5zaWQ9NTEzOA&ptn=3&fclid=4810c6a9-e965-11ec-8397-20a9ab92ca58&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvQ2hhcnlhcGFkYQ&ntb=1

[20] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=cdca935a0af8ccbcb22270b6c1ed93b8a92d048d7829d9043a5f4c1b4277f382JmltdHM9MTY1NDkzODI4NyZpZ3VpZD1hMDFhNzBjNi0wZTUwLTRlMzYtYmU4MS1iMDE0ZDM3NzhkOTEmaW5zaWQ9NTE2NQ&ptn=3&fclid=8ab83a38-e965-11ec-8703-c3d3f4b75dd2&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuYnJpdGFubmljYS5jb20vdG9waWMvbWFuZ2FsLWthdnlh&ntb=1

[21] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=b8e53168655f0641624f6644e841c6d67891baca86dae6548d1c7504365bd7b4JmltdHM9MTY1NDkzODQ5MSZpZ3VpZD1hNzkzM2M5OC1lYWM0LTRlY2UtOTU5Yy1iNDM0ZGZiZjRlNTMmaW5zaWQ9NTE0NA&ptn=3&fclid=04232375-e966-11ec-bde6-c2fa5b3df234&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvQW5uZW1hcmllX1NjaGltbWVs&ntb=1

[22] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=dc0d9d7c557453001e33443ed974c22a31b81911e1938f20263c3e249f328e57JmltdHM9MTY1NDkzMzI2OCZpZ3VpZD03NzExMDk5Yi1kNzU3LTRkNmQtYTE2MS1mMTRiM2RjNTczYTEmaW5zaWQ9NTE2MQ&ptn=3&fclid=db6dc217-e959-11ec-bbbf-36cc92968094&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvSXNhYWNfQ3J1aWtzaGFuaw&ntb=1

[23] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=36efb3c8c97c9fbd3236a03da3166d86cce9468656b4bbdac5bf2efc621d622cJmltdHM9MTY1NDk0MDcwNyZpZ3VpZD1iMTdjMWY0Yy00YWI4LTRkNDgtOGE0NS04MmZjZDhhY2JiNGEmaW5zaWQ9NTQxNw&ptn=3&fclid=2d05cc04-e96b-11ec-9527-c34934558146&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9zdG11c2Nob2xhcnMub3JnL3RoZS1leGVjdXRpb24tb2YtbWFyaWUtYW50b2luZXR0ZS10aGUtbGFzdC1xdWVlbi1vZi1mcmFuY2UvIzp-OnRleHQ9VGhlJTIwaGVhZCUyMG9mJTIwTWFyaWUlMjBBbnRvaW5ldHRlJTJDJTIwZGVzaXJlZCUyMGJ5JTIwdGhlLEtpbmclRTIlODAlOTlzJTIwYm9keSUyMGhhZCUyMGJlZW4lMjBsZWZ0JTIwbmluZSUyMG1vbnRocyUyMGVhcmxpZXIu&ntb=1

[24] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=29fa1031c23b110c9a5000ea93b99469d748e1ce7f52d7acd13af7e8f2f83a9dJmltdHM9MTY1NDk0MTEyNCZpZ3VpZD1jYzdlMDAwMS0yY2M4LTQwZjMtYjI0Ny0zMGI2MmMyNzRhOTUmaW5zaWQ9NTEyNg&ptn=3&fclid=25a289e6-e96c-11ec-a755-06106ec6de1e&u=a1aHR0cDovL3d3dy5jYmtvcnRzY2guY29tL2RyZXNzY3VsdHVyZQ&ntb=1

[25] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=c623352d2180a4f6857bedfe2bb79663b34ed604a19a7a65b869f0dd77c62f0dJmltdHM9MTY1NDk0MTI2NiZpZ3VpZD1lMDEyOWIyZC1mMGVmLTQwNTItOGY2NS02ZjMyNjA3YTQxYTEmaW5zaWQ9NTE4NQ&ptn=3&fclid=7a7a8c0f-e96c-11ec-b8aa-96a49688fbd0&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvSW5kdXN0cmlhbF9SZXZvbHV0aW9u&ntb=1

[26] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=b1c055419aa284aff4f587df9336ef0ab262288e64e682a7969664e05ae4099cJmltdHM9MTY1NDk0MTM1NiZpZ3VpZD1hMDNkYzIxMi1jOThiLTQ2MWItYjRmMC03YTUyMDk0ZGRhMWMmaW5zaWQ9NTM4NA&ptn=3&fclid=b01aa1b0-e96c-11ec-84be-f75f1eee290d&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvSmFtZGFuaSM6fjp0ZXh0PUphbWRhbmklMjAlMjhCZW5nYWxpJTNBJTIwJUUwJUE2JTlDJUUwJUE2JUJFJUUwJUE2JUFFJUUwJUE2JUE2JUUwJUE2JUJFJUUwJUE2JUE4JUUwJUE2JUJGJTI5JTIwaXMlMjBhJTIwZmluZSUyMG11c2xpbiUyMHRleHRpbGUscGF0cm9uaXplZCUyMGJ5JTIwaW1wZXJpYWwlMjB3YXJyYW50cyUyMG9mJTIwdGhlJTIwTXVnaGFsJTIwZW1wZXJvcnMu&ntb=1

[27] https://www.sgbgatelier.com/world/2019/11/21/5-ways-imperial-britain-crippled-indian-handlooms

[28] Das, G. 2002. “If We Were Once Rich, Why Are We Now Poor?” In: India Unbound. New Delhi: Penguin Books. 52-63.

[29] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=2da6bbc00240f020a373d4e090b876ee09aa34b21e19846d475d92ae88c182afJmltdHM9MTY1NDk0MzAyMCZpZ3VpZD02ZDZjODExMy0zMzM4LTQ2YTAtYWJiYy1lMWJjNmRjNmY2OGImaW5zaWQ9NTM4NQ&ptn=3&fclid=8fa193ca-e970-11ec-bc08-2c6fe522e52f&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZnJlZW9ubGluZXJlc2VhcmNocGFwZXJzLmNvbS9mYWxsLXRleHRpbGUtaW5kdXN0cnktaW5kaWEv&ntb=1

[30] Irwin, J. 1919. “Indian Textile Trade in the Seventeenth Century, Foreign Influences.” Journal of Indian Textile History 4: 58.

[31] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gossypium_arboreum

[32] The Legendary Fabric That No One Knows How to Make, BBC

[33] https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20210316-the-legendary-fabric-that-no-one-knows-how-to-make

[34] slam, Khademul. 2016. Our Story of Dhaka Muslin. AramcoWorld. Volume 67 (3). May/June 2016. Pages 26-32. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/895830331

[35] https://www.aramcoworld.com/Articles/May-2016/Our-Story-of-Dhaka-Muslin#:~:text=Although%20muslin%20weaving,than%20a%20profession.%E2%80%9D

[36] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=5f3609c480540162001c4a810e03cd062ae5328e16a40523d1f66721cb096509JmltdHM9MTY1NDkzOTE1NyZpZ3VpZD0xN2NhNDVhMC01NTJmLTQxNTQtOTE5MC0xZDY4MTdmMTRjNDcmaW5zaWQ9NTE3OQ&ptn=3&fclid=913f045e-e967-11ec-888c-0d9834c940d3&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9saWdodHRyYXZlbGFjdGlvbi5jb20vd2hhdC1pcy1pbmRpYW4tcGFhbi13aGF0LWlzLXRoZS1yaWdodC13YXktdG8tZWF0LWl0Lw&ntb=1

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: British Colonialism, British empire, India

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 13 Jun 2022.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: The Targeted Death and Extinction of Muslin by British Imperialism, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.