Peace Propagators (Part 1): The Sufi Spiritual Masters

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 13 Mar 2023

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

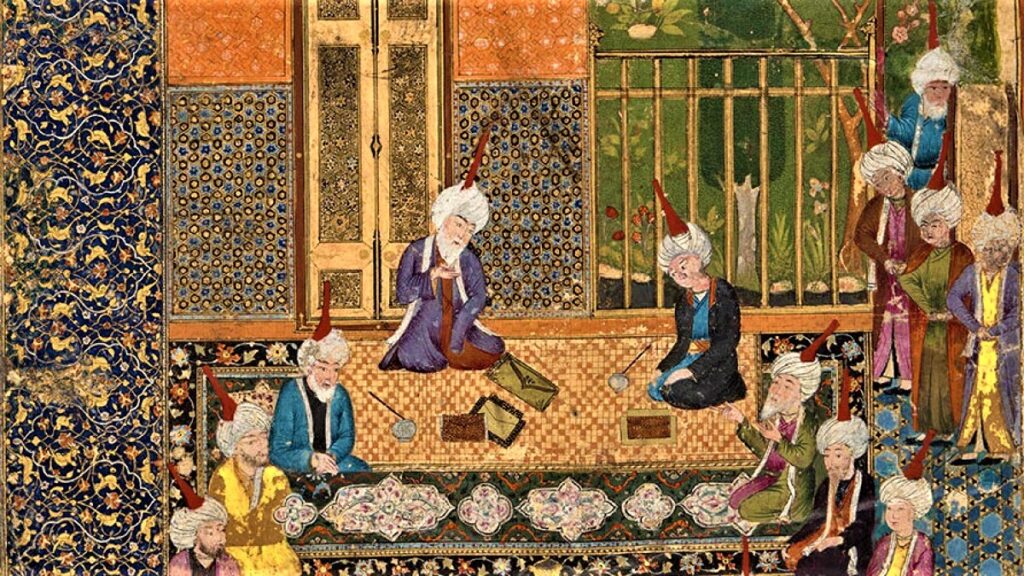

An illustrated copy of The Mas̱navī-ʼi maʻnavī by Jalāl-al-Dīn Rūmī (d. 1273) was composed in the 13th century and is a monumental work of poetry in the Sufi tradition of Islamic mysticism. Divided into six books, it has served as an inspiration for Sufis and others worldwide and is today perhaps the best-known work of Persian literature.

Photo: British Library

“Spirituality, Not Religiosity, Is the Strongest Pillar of Peace”[i]

11 Mar 2023 – This publication discusses the global following of Sufism, as an originator and protagonist of Peace. Sufism is a way of life in which a deeper identity is discovered and lived. This deeper identity, beyond the already known personality, is in harmony with all that exists. This deeper identity, or essential self, has abilities of awareness, action, creativity and love that are far beyond the abilities of the superficial personality. Sufism is a mystical form of Islam that emphasizes the development of a direct personal relationship with God through practices such as meditation, chanting, and dancing. At its core, Sufism is based on the belief that the ultimate goal of human life is to achieve a state of spiritual enlightenment and union with the divine.

The essence of Sufism can be distilled into several key principles:

- Love of God: Sufism emphasizes the importance of cultivating a deep love and devotion for God as the path to spiritual enlightenment.

- Self-Knowledge: Sufism emphasizes the importance of self-knowledge and self-awareness as the first step towards spiritual growth.

- Humility: Sufis believe that true spiritual progress requires humility, and that the ego must be overcome in order to achieve union with the divine.

- Service: Sufis believe that serving others is a path to spiritual growth and that the ultimate goal of spiritual practice is to be of service to humanity.

- Unity: Sufism emphasizes the unity of all beings, and that the ultimate reality is one divine consciousness that underlies all of creation.

- Sufism attaches much significance to the concept of tolerance, across all cultures, beliefs, traditions and religions.

- Overall, the essence of Sufism is a deeply spiritual and mystical approach to Islam that emphasizes the pursuit of a direct personal relationship with God through practices of love, self-knowledge, humility, service, and unity.

Defining any para-religious entity is extremely difficult and fraught with the risk of displeasing the propagators of the organisation. Sufism is one such grouping amongst the followers of Islam, which is a way of life, as an Abrahamic religion and founded by Prophet Abū al-Qāsim Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib ibn Hāshim, (Peace Be Upon Him)[2] (born c. 570, Mecca, Arabia, demised June 8, 632, Medina), the proclaimer of the Qurʾān[3], 1444 years ago, in the small town of Mecca, in present day Saudi Arabia. It is to be understood that Sufism is not a religion, nor a break away group from the main body of followers of Islam, as such. It is a philosophy which espouses the direct contact and the development of a relationship of humanoids with the Divine creator. Sufism has been defined in different ways by scholars of Islam[4], both from within the Muslim tradition and from outside of it. The debate on the nature, reality and essence of Sufism reflects the plurality of ways in which Sufism has manifested itself historically and geographically, resulting in a plethora of forms that sometimes bear little resemblance to one another.

Sufism is often defined as the mystical or esoteric strand of Islam, Sufism’s defining feature is the centrality of the individual’s direct relationship with God. The individual devotee strives towards establishing a direct, inner connection with God, or the acquisition of a transformative knowledge of the Divine. Another way the Sufis have often described the inner experience of the Divine is through the symbolism of the veil: because the inner reality of human life is nothing but God itself, true self-knowledge amounts to the knowledge of God, which can be attained by removing the veils which cover a humanoid’s true nature and prevent them from seeing God within themselves.

The question often raised is where did Sufism originate from and where did Sufism begin? Central aspects of Sufism, such as the continuous remembrance of God, love for him and his creatures and the effort to transcend the mundane concerns in favour of the eternal joys of the divine world, are clearly found in the Qur’an and the Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) exemplary character. However, Sufism as a historical phenomenon emerged in the 7th or 8th centuries CE through the preaching of a movement of ascetics, and developed in Baghdad in the 9th and 10th centuries around some charismatic figures, the most influential of which is the master Junayd al-Baghdadi (d. 910). From present day Iraq, it quickly spread throughout the rest of the Islamic territories, contributing to the conversion of the new populations that came under the control of Islamic rulers and deeply influencing the religious thought, the culture, the traditions, the arts and the literatures of these geographical regions, under Islam.[5]

The question often raised is what is Afghanistan’s contribution to Sufism. Afghanistan has a rich and diverse history of Sufism, with many notable Sufi saints, scholars, and poets hailing from the country. Afghan Sufis have made significant contributions to the development and spread of Sufism, both within Afghanistan and beyond.

One of the most famous Afghan Sufis is the 12th-century poet and mystic Jalaluddin Rumi[6], who was born in Balkh, in present-day Afghanistan. Rumi’s poetry has become renowned around the world for its spiritual depth and beauty, and he is considered one of the greatest Sufi poets of all time. Other notable Afghan Sufis include the 14th-century saint and poet Khwaja Abdullah Ansari, also known as Pir-e-Herat, who was born in Herat and is revered as a spiritual master by Sufis across the Muslim world. Another important figure is Bayazid Ansari, a 16th century Sufi master who founded the Bayazidiyya Sufi order and whose teachings had a significant impact on the development of Sufism in Afghanistan. Throughout its history, Afghanistan has been home to many Sufi orders, each with their own distinct practices and teachings. Some of the most prominent orders in Afghanistan include the Naqshbandiyya, the Qadiriyya, and the Chishtiyya. Despite the challenges of war and conflict in recent years, Sufism remains an important part of Afghan culture and spirituality, with many Sufi shrines and traditions still thriving in the country today.

The Sufi in general perform certain rituals and practices which vary from country to region. One such practice is the Qawwali, a devotional Sufi music, is sung at various Sufi gatherings and celebrations. These compositions, to the accompaniment of indigenous music performed on unique instruments often contain lyrics glorifying Allah and praising Prophet Muhammad PBUH. Other Sufi practices includes zikr, construction of various Khanqahs to spread Islam.[7] The Naqshbandi tariqa or order is one of the most dominant Sufi orders in Afghanistan.[8] The Mujaddidiya branch of the Naqshbandi tariqa is said to influential to the present day. Pir Saifur Rahman is one of the notable Sufi of this order.[9] The other affiliates of the Naqshbandi order are Ansari, Dahbidi, Parsai, Juybari.[10] The other Sufi orders followed in Afghanistan are Qadriyya and Chishti Order.[11]

Milad-un-, the Islamic birthday of the Prophet, is celebrated by Sufis in Afghanistan.[12] The various belongings of Muhammad such as Moo e Mubarak (Muhammad’s Hair), Khirka Sharif, are sacred things for Sufis in Afghanistan, and they have built shrines around the artefacts of the messenger of God..[13]

In terms of beliefs, people in Afghanistan regard Sufi shrines as places to unburden themselves, sharing their problems at the feet of Sufi saints, believing the saint can intercede on their behalf. It is a strong belief that prayer by a Sufi saint can eliminate poverty, cure illnesses, improve relations with loved ones and ease from various ills of life. When people become helpless after using all the possibilities in their hands then they refer to Sufi saints. Sufi saints are considered as the representatives of Allah who can build their relationship with Allah and all their desires, through the Saint, can be directly heard and fulfilled by Allah, in view of their spiritual closeness and piety.[14]

The suppression of Sufi practices in Afghanistan was a sad era for Sufism. At the height of ISIS rise, in 2018 around 50 religious scholars were the victim of suicide bombing during the Mawlid celebration in Afghanistan[15]. The official recognition of Sufism was done by the former president of Afghanistan Sibghatullah Mojaddedi who was also a Sufi Sheikh. Sufis in Afghanistan are known for their miraculous powers. Pilgrimage to Sufi shrine (Ziyarat) is recognised in all of Afghanistan.[16] The following is a list of notable Afghani Sufis and Afghanistan is the birthplace of many Sufis, such as[17]:

- Hakim Sanai (Ghazni)

- Hakim Jami (Herat)

- Sheikh Mohammad Rohani

- Khwaja Abdullah Ansari

- Sibghatullah Mojaddedi

- Ahmed Gailani

- Abobaker Mojadidi

- Mullah Omar

- Rumi

Sufism changed over the centuries in its manifestations, accommodating local cultures by a process of enculturation and taking on different languages, in turn providing them with ideas and concepts which came to be part of the language, the literature and the popular culture. However, the main character of Sufism, which can be summarised with the term ‘esotericism’ (from the ancient Greek esōtérō, ‘further inside’), remained the common denominator of the multiple manifestations of Sufism in virtually every time and place. The esoteric essence of Sufism points to the double meaning of being within an individual devotee, and within the inner circle of the chosen ones. Sufi terminology uses the complementary terms of zahir (‘that which is external’, the exoteric) and batin (‘that which is inner’, the esoteric); these terms refer to the fact that everything existing has an outer appearance and an inner reality.

From the natural phenomena of the cosmos, to human beings and the Qur’an itself, everything has a literal, immediately perceptible meaning and a deeper, true reality. The Sufi’s aim is the attainment of this true reality, and thus Sufism is described as a path from the exoteric to the esoteric, the ultimate station of which is the knowledge (ma‘rifah) of God and union with him. This path, the Sufis believe, can be attained through a series of rituals and practices that vary across the different mystical schools, but which cannot be effectively performed without the guidance of a master (shaykh) who has already trod the whole path, whose authority is certified through an uninterrupted chain (silsilah) of other masters (often referred to as awliya’ Allah, ‘friends of God’, because of their intimacy with the secrets of the Divine) that connects him back to the Prophet Muhammad(PBUH).

The spiritual chain connecting the saints to Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) highlights the importance of the biographical genre in Islam in general, and Sufism in particular. The biographical literature on Prophet Muhammad serves as both a repository of information about the life of the Prophet and as a means for the development of a devotional attitude towards him as an exemplary model of conduct. Biographies of Sufi saints were produced by Sufi literati with the double aim of preserving information about important masters of peace, and of providing practitioners with examples of asceticism, devotion and piety.

Sufi biographies often focus on reports (akhbar) combining noteworthy events, morality tales, and miraculous stories where historical reality is mixed with hagiographical elements[18], rather than a comprehensive account of the saint’s life. Among these works the Persian mystical poet Farid al-Din ‘Attar’s (d. 1221) only surviving prose work, the Tadhkirat al-awliya’ (Biography of the Saints), stands out. The Tadhkirat is a collection of the biographies of seventy-two Sufi saints, beginning with the sixth Imam of Shi‘a Islam, Jaʿfar al-Sadiq (d. 765), and ending with the life of the celebrated Sufi martyr Mansur al-Hallaj (d. 922), encompassing such great mystics as Hasan al-Basri, the female saint Rabi’a al-ʿAdawiyya, and the great jurists Abu Hanifa and al-Shafiʿi.

The entire Sufidom has developed into different orders of Sufism, depending upon the country, Sufism is practiced. Sufism is a diverse and complex tradition with many different orders, also known as tariqas, each with their own unique practices, teachings, and history. Some of the most prominent Sufi orders and their origins are documented as follows:

- The Qadiriyya order was founded in the 12th century by Abdul-Qadir Gilani in Baghdad, Iraq. It spread throughout the Muslim world and is now one of the most widespread Sufi orders, with branches in many countries including Pakistan, India, and Morocco.

- The Naqshbandiyya order was founded in the 14th century by Baha-ud-Din Naqshband in Bukhara, present-day Uzbekistan. It emphasizes the importance of remembrance of God and has been influential throughout Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent.

- The Chishtiyya order was founded in the 12th century by Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti in India. It emphasizes the importance of love, devotion, and service to humanity, and has been influential throughout South Asia.

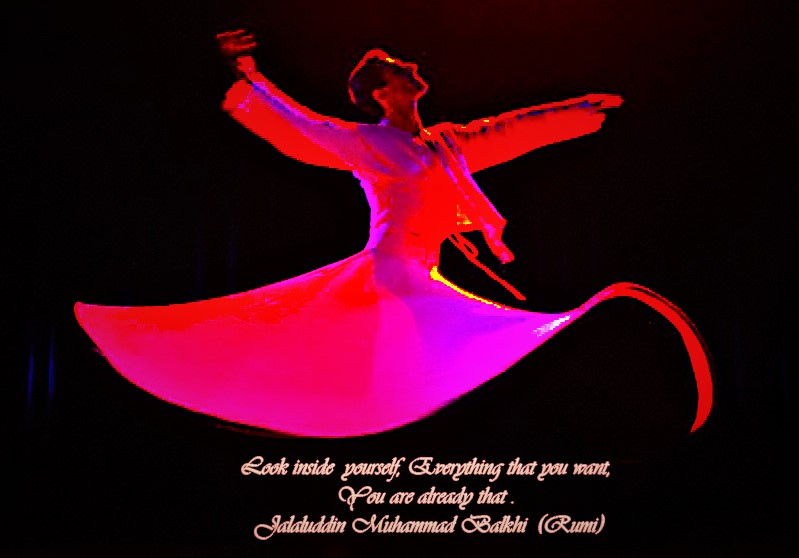

- The Mevleviyya order, also known as the Whirling Dervishes, was founded in the 13th century by Jalaluddin Rumi in Konya, Turkey. It is known for its distinctive form of worship, which involves spinning in circles as a form of meditation and devotion.

- The Shadhiliyya order was founded in the 13th century by Abu-l-Hassan ash-Shadhili in Egypt. It emphasizes the importance of spiritual discipline and has been influential throughout North Africa and the Middle East.

- The Rifaiyya order was founded in the 12th century by Ahmed ar-Rifai in Baghdad, Iraq. It is known for its emphasis on ecstatic worship and has been influential throughout the Muslim world.

These are a few of the many Sufi orders which exist throughout the world, and each has its own unique history as well as influence within the broader traditions of Sufism. Regarding which Sufi order has the largest following, globally, remains difficult to determine, as there are no official records or statistics available. However, some of the largest and most widespread Sufi orders include the Qadiriyya, the Naqshbandiyya, and the Chishtiyya. The Qadiriyya order is known for its emphasis on simplicity and the use of music and dance in spiritual practice. It has a strong presence in West Africa, particularly in countries like Senegal, Mali, and Niger. The Naqshbandiyya order is known for its emphasis on silent meditation and the practice of remembrance of God. It has a strong presence in Central Asia, particularly in countries like Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan. The Chishtiyya order is known for its emphasis on love, devotion, and service to humanity. It has a strong presence in South Asia, particularly in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Overall, Sufism is a diverse and decentralised tradition, and there are many different Sufi orders with followers around the world. While some orders may be more prominent in certain regions or countries, there is no one order that can claim to have the largest following, globally.

Another aspect, is whether all branches of Islam support and accept Sufism or are there any detractors of the philosophy of global peace? Sufism is a branch of Islamic mysticism that has been practiced and accepted by many Muslims throughout history, but there have also been some detractors of the philosophy within the Muslim community. Some conservative and orthodox Muslims have criticised Sufism, viewing it as a deviation from the teachings of the Quran and the example of the Prophet Muhammad PBUH. They argue that some Sufi practices, such as ecstatic worship and the veneration of Sufi saints, can lead to “shirk”, or the association of partners with God, which is considered a major sin in Islam. In some cases, governments and religious authorities have also targeted Sufi communities and practices, viewing them as a threat to their authority or as promoting unorthodox beliefs. For example, in some countries like Saudi Arabia and Iran, Sufi practices have been restricted or banned at various times. However, it is important to appreciate that these criticisms and restrictions are not universally held within the Islamic community, and many Muslims around the world practice and embrace Sufism as a legitimate and important aspect of Islamic spirituality. Sufi ideas and practices have had a profound influence on Islamic art, literature, and culture, and continue to inspire many Muslims to this day.

Regarding the freedom of practice of Sufism under the regimes of Saddam Hussein in Iraq, prior to his overthrow in 2003, after spending nine months on the run, former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was captured on 13th December 2003. Saddam’s downfall began on 20th March 2003, when the United States led an invasion force into Iraq to topple his government, which had controlled the country for more than 20 years. A similar overthrow awaited the Shah of Iran before the revolution, when he escaped to the United States. Sufism was practiced in Iraq and Iran during the regimes of Saddam Hussein and the Shah of Iran, but the extent to which it was allowed or encouraged varied depending on the specific political context and policies of each regime. Under Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq, Sufi practices were not explicitly banned, but they were not officially recognised or supported either. The Ba’athist regime sought to promote a secular and nationalist ideology, and religious groups, including Sufi communities, were generally viewed with suspicion. However, some Sufi communities in Iraq continued to practice and maintain their traditions despite this lack of official recognition.

In Iran, Sufi orders were generally tolerated and supported under the regime of the Shah. The Shah was himself a follower of the Ni’matullahi order of Sufism, and he encouraged the promotion of Sufi teachings and practices as a way to counter the influence of more conservative and political forms of Islam. Many Sufi orders in Iran were allowed to establish their own schools and centers of worship, and some even received government funding.

The status of Sufism under President Erdogan in Turkey is a complex and multifaceted issue, as Sufism has played an important role in Turkish history and culture, but its relationship with political power has been subject to various interpretations and controversies. On the one hand, President Erdogan and his ruling party, the Justice and Development Party (AKP), have sought to promote a conservative and traditionalist version of Islam that emphasizes the role of the state in regulating religious affairs. This approach has sometimes led to tensions with certain Sufi communities, who view themselves as independent and autonomous spiritual organizations that are not subject to state control. At the same time, President Erdogan and the AKP have also sought to embrace Sufi symbolism and imagery as a way to appeal to a broader Muslim audience, both in Turkey and beyond. For example, President Erdogan has often been seen wearing a green tie, which is a symbol associated with Sufism, and he has used Sufi imagery in his speeches and public appearances. Overall, the relationship between Sufism and the Turkish government under President Erdogan is complex and multifaceted, and it is difficult to make generalisations about the status of Sufism in Turkey at present. Some Sufi communities have been able to maintain their traditions and practices relatively unimpeded, while others have faced challenges and obstacles from the government and other political actors.

It is also interesting to understand what aspects of Sufism did the Prophet Muhammad PBUH, practice and propagate. It is believed that the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, practiced and propagated many aspects of Sufism, particularly those related to the pursuit of spiritual knowledge and the cultivation of a deep personal relationship with God. One of the central themes of Sufism is the concept of tawhid, or the unity of God. This idea is rooted in the Quranic teachings that God is the One and Only Creator and Sustainer of the universe, and that all things are ultimately dependent on Him. The Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, emphasized this idea in his teachings and in his own practice, emphasizing the importance of sincere worship and devotion to God alone. Another important aspect of Sufism that is closely associated with the Prophet Muhammad’s teachings is the cultivation of a personal relationship with God through the practice of dhikr, or remembrance of God. The Prophet Muhammad is reported to have said that “the closest a servant is to his Lord is when he is in prostration,” emphasising the importance of prayer and meditation as a means of drawing closer to God. In addition, the Prophet Muhammad is also believed to have emphasised the importance of humility, compassion, and love in one’s relationship with God and with other people. These values are central to many Sufi teachings, which emphasize the importance of cultivating a deep sense of empathy and compassion for all of God’s creatures. Overall, while Sufism as a distinct spiritual tradition emerged after the Prophet Muhammad’s time, many of its core values and teachings are closely linked to the Prophet’s own teachings and practice.

There were also other prophets before Prophet Muhammad PBUH, promote aspects of Sufism, though not formally recognized, as such since, while the term “Sufism” as a distinct spiritual tradition emerged after the time of the Prophet Muhammad, many of its core values and practices are rooted in the teachings of earlier prophets and spiritual figures in the Islamic tradition. For example, many Sufi teachings emphasize the importance of humility, compassion, and love, which are values that are also emphasized in the teachings of earlier prophets such as Abraham, Moses, and Jesus. These prophets all emphasized the importance of submitting oneself to God and cultivating a deep sense of compassion and empathy for all of God’s creatures. Similarly, many Sufi practices, such as meditation, prayer, and the pursuit of spiritual knowledge, have roots in the teachings and practices of earlier prophets and spiritual figures. For example, the Prophet David is said to have engaged in prolonged periods of meditation and prayer, while the Prophet Solomon is said to have been granted great wisdom and knowledge by God. Holistically, while the term “Sufism” may not have been used to describe these earlier spiritual traditions, many of the core values and practices of Sufism have deep roots in the teachings of earlier prophets and spiritual figures in the Islamic tradition.

Another point often raised is that Iman Hussein, the grandson pf the Prophet Muhammad PBUH, a Sufi, noting his green traditional colour, in his attire. However, there is no historical evidence to suggest that Imam Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, was a Sufi. While the color green is often associated with Sufism, it has many other cultural and religious connotations as well, and the use of the color green by Imam Hussein or his followers does not necessarily indicate an affiliation with Sufism. Imam Hussein is primarily known for his role in the early history of Islam as a political and religious leader, and as a figure of great spiritual and moral significance to many Muslims. His martyrdom at the Battle of Karbala is widely regarded as a defining moment in Islamic history and has been commemorated by Muslims around the world for centuries. While Sufi teachings and practices have played an important role in the development of Islamic spirituality over the centuries, it is important to recognize that not all Muslims throughout history have identified as Sufis or been associated with the Sufi tradition. The use of the color green by Imam Hussein or his followers may have been based on cultural or religious traditions that predated or were separate from the development of Sufism as a distinct spiritual tradition.

Furthermore, it is regularly enquired if the celebration of Muharram, the Islamic New Year and the martyrdom of Imam Hussein in Karbala, observed in Shia countries associated with Sufism? While the celebration of Muharram is primarily associated with Shia Islam and is observed in many Shia countries around the world, it is not directly linked to Sufism as a distinct spiritual tradition. Muharram is the first month of the Islamic calendar and is a period of mourning and reflection for many Shia Muslims, who commemorate the martyrdom of Imam Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, at the Battle of Karbala in 680 CE. During this time, Shia Muslims engage in a variety of rituals and observances, including recitation of elegiac poetry, reenactments of the events at Karbala, self-flagellation, fasting and public processions of hand made “Tahziyas[19] or Shia pagodas” of different sizes and elaborate intricacy. While these customs are not supported by mainline Islamic jurisprudence, they are widely practiced as a remembrance of the martyrdom of Imam Hussein.[20] While some Sufi orders may also observe Muharram as well as participate in these rituals and observances, the celebration of Muharram is primarily associated with Shia Islam and is deeply rooted in Shia theology and history. As such, it is important to recognize that while there may be some overlap between Sufi and Shia practices and beliefs, they are distinct spiritual traditions with their own unique histories and teachings, often sprinkled with syncretism between the two dominant philosophies, especially in the Middle East.

It is also pertinent to discuss what aspects of Sufism did the Prophet Muhammad practice and propagate. In this regard, it is believed that the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, practiced and propagated many aspects of Sufism, particularly those related to the pursuit of spiritual knowledge and the cultivation of a deep personal relationship with God. One of the central themes of Sufism is the concept of tawhid, or the unity of God. This idea is rooted in the Quranic teachings that God is the One and Only Creator and Sustainer of the universe, and that all things are ultimately dependent on Him. The Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, emphasized this idea in his teachings and in his own practice, emphasising the importance of sincere worship and devotion to God alone. Another important aspect of Sufism which is closely associated with the Prophet Muhammad’s teachings is the cultivation of a personal relationship with Godis through the practice of dhikr, also spely zikr, or remembrance of God. The Prophet Muhammad is reported to have said that “the closest a servant is to his Lord is when he is in prostration,” emphasising the importance of prayer and meditation as a means of drawing closer to God. In addition, the Prophet Muhammad is also believed to have emphasized the importance of humility, compassion, and love in one’s relationship with God and with other people. These values are central to many Sufi teachings, which highlight the importance of cultivating a deep sense of empathy and compassion for all of God’s creatures. Overall, while Sufism as a distinct spiritual tradition emerged after the Prophet Muhammad’s time, many of its core values and teachings are closely linked to the Prophet’s own teachings and practice, by personal example.

Another aspect which needs to be elaborated upon is Sufism associated with Judaism and Christianity as well as other Abrahamic religions? While Sufism is primarily associated with Islam, it has been influenced by and has influenced other religions, including Judaism and Christianity. Sufi thought and practices have been compared to Jewish mystical traditions such as Kabbalah and to Christian mysticism, particularly in the works of figures like the Christian mystic Meister Eckhart. Some Sufi poets, such as Rumi, have also explored themes that are universal and relevant to all human beings, regardless of their religious background. Therefore, Sufism has been seen as having cross-cultural and interfaith potential for promoting understanding and harmony.

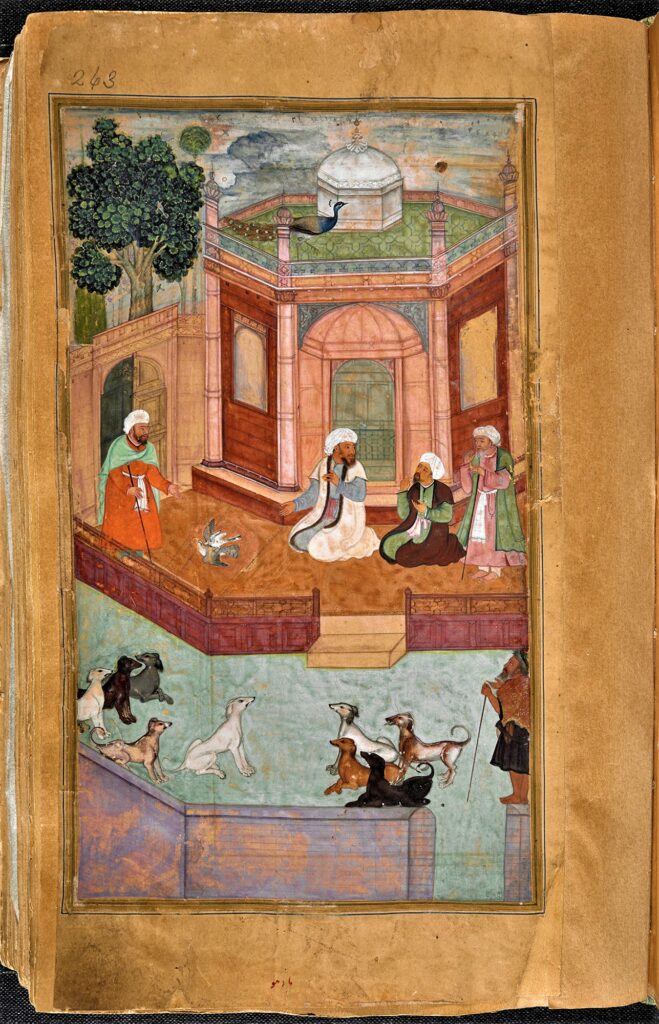

An imperial copy of Jami’s Nafaḥāt al-uns, copied for the Mughal Emperor Akbar in 1604–1605. It consists of 567 biographies of Muslim saints and mystics, dating from the 8th to the 15th century, followed by a section on Sufi poets and ending with accounts of female saints. The author was the celebrated Persian poet, scholar and Sufi, ʻAbd al-Raḥmān Jāmī who died at Herat in 1492.

(Photo credit: British Library)

Regarding the doctrines the shaykh and the Sufi orders, there is a rigorous protocol. The Sufi is expected to go through ascending spiritual stations (maqamat) ultimately conductive to a direct experience of the truth. This path may encompass visionary experiences and ecstatic states (hal). It is often described as moving up to the stage of ‘annihilation’ (fana) of the self, with the final goal being the return of self and subsistence in God (baqa). Existence in the world of multiplicity is therefore somehow illusory, true existence being an attribute of the only God, i.e. it is an attribute of unity. Among the celebrated Sufi masters who better formulated this idea (often referred to as the doctrine of the ‘unity of the being’, wahdat al-wujud), is the Andalusian metaphysician Muhyi al-Din Ibn ‘Arabi [21](d. 1240), who exerted an influence on subsequent Muslim thought comparable to that exerted by Plato on Western philosophy. Faithful to the Qur’anic tenet that nothing on earth is permanent except the face of God (Q. 28. 88: All things perish, except His Face), the Sufi’s ultimate goal is to get rid of their ego and the world of multiplicity to subsist in communion with God in the abode of unity.

The starting point of this journey is initiation into a Sufi order (tariqah). Sufi initiation, as well as being a ritual believed to transmit a transformative spiritual influence (barakah), represents a formal covenant (bay’a) through which the disciple commits to obey the master. The bond between the shaykh and the disciple (murid) is therefore a very important one. In the 10th and 11th centuries the model of this relationship reshaped Sufism, from a network of informal and often trans-regional mystical and ascetic circles, to a series of institutions with a defined hierarchical structure, often endowed with a high social relevance, financial resources and sometimes political clout. It is the social standing of the shaykh as the head of these institutions that facilitated the birth of what has been defined as ‘organised Sufism’ or ‘tariqah Sufism’, which is the form of Sufism still prevalent today.

A question often raised is how do Sufis interpret the Islam scripture, The Qur’an?[22] In order to delve into the batin, or the inner meaning, of the Qur’an, Sufis made major contributions to the Islamic exegetical tradition. Sufism offered a creative insight, firmly rooted, however, in the scriptural and authoritative tradition. In Sufi exegesis, the esoteric meaning of the text is explored, and the understanding of the scripture is looked at as a veritable mystical practice that opens up ways for a transformative knowledge. For Sufis, understanding the Qur’an is a religious experience rather than an intellectual and rational one. Sufi authors such as Abd al-Rahman Sulami (d. 1021), Abu al-Qasim al-Qushayri (d. 1073), Rashid al-Din Maybudi (fl. early 12th century) and Ibn ‘Arabi all wrote works of Qur’anic exegesis that had a lasting impact on the subsequent exegetical tradition. Some exegetical material produced by Sufi writers is written in poetical forms. One such case is the celebrated Masnavi, a voluminous poem famously praised in the Persian-speaking world as ‘the Qur’an in the Persian language’. Written by Jalal al-Din Rumi (d. 1273), one of the greatest stars of the firmament of Sufi poetry, the Masnavi is so closely informed by the Qur’an and its mystical interpretation that it can be regarded, as well as the poetic masterpiece that it is, as a work of Qur’anic exegesis in its own right.

In Sufi, what are the Qur’anic pericopes: Yusuf and Zulaykha. Sufi poets often reflected on the Qur’anic text and used it as an inspiration for their poems. Among the literatures heavily informed by Sufi thought, Persian literature, in particular poetry, has a special place. It has served as education for the Persian-speaking peoples across the classes since its inception.

The pericopes in particular (narrative units often illustrating stories of pre-Islamic prophets) have been a source of Qur’anic inspiration to Persian poets. The Qur’an is punctuated by these pericopes, narrating stories of Jesus, Moses, Jonah and other biblical personae. The story of Prophet Joseph and Zulaykha, widely known as the story of Joseph and Potiphar in the Book of Genesis, was particularly fascinating to the Sufi imagination, as it narrates the story of a young and handsome man (Jospeh/Yusuf) who resists the advances of the older and wealthy Zulaykha, who is identified as the wife of the Egyptian officer who bought Yusuf as a slave from his brothers (Zulaykha is not named in Genesis, while Potiphar is not named in the Qur’an).

The story has been narrated in Persian poetry a number of times by different poets, and it underwent several elaborations and expansions. The most famous of these poetic renderings is the one offered by the 15th century Persian Sufi poet Abd al-Rahman Jami, who devotes one of the seven books of his Haft-awrang (Seven Thrones) to the story. Jami’s Yusuf and Zulaykha became a classical example of Sufi interpretation of Qur’anic narrative material expressed in verses, and one of the masterpieces of Sufi erotica-mystical poetry. In the work, love for the Divine is addressed through the symbolisation of the human characters of the protagonists, and Jami masterfully blends different streams of the intellectual history of Islam: Avicenna’s philosophical cosmology, Ibn ‘Arabi’s metaphysics and the tradition of classical Persian mystical poetry.

The quest for truth is reflected in the Sufi poetry: ʿAttar’s Mantiq al-tayr. Love is one of the preferred themes of Persian Sufi poets, both for its narrative potential and for its relevance as a spiritual driving force. The spirits of the friends of God, the Sufi theoretician of erotic mysticism Ruzbehan Baqli (d. 1210) says, became intoxicated with the Divine word and fall in love with God, the eternal beloved, through the contemplation of his beauty. This attractive power leads the Sufi to shed all traces of individuality and temporality, attaining the ultimate goal of annihilation and subsistence in God, which is the last station of the path. Sufi poets have described this union in countless ways, relying on their creative imagination and their visionary experiences, coupled with masterful poetical skills.

Among the most successful and imaginative Sufi poets is the already mentioned Farid al-Din ‘Attar. ‘Attar is the most important Persian Sufi poet of the second half of the 12th century, and is best known for his Mantiq al-tayr (The Conference of the Birds). This work is often regarded as the finest example of Sufi poetry after that of Rumi.

Bowl of Reflections inscribed with Rumi’s poetry. Early 13th century, Brooklyn Museum. (TRT World and Agencies)

This epic poem vividly depicts the tale of thirty birds on a journey to find their supreme master, called the Simurgh. In the end the birds realise that they themselves are the Simurgh, the name being composed of the two Persian words si (thirty) and murgh (bird). The quest symbolises the human soul’s quest to find its true reality, which is ultimately the self freed from the delusion of multiplicity. ‘Attar’s Conference of the Birds draws on the work of another great Sufi master, Ahmad Ghazali (d. 1126), who had written a similar story half a century earlier, but ‘Attar’s masterful craft elevated it to the fame it has today. ‘Attar’s epic masterpiece has also been turned into a number of musical and theatrical plays in the Persian world as well as in the West, and its colourful stories provided abundant material for illustration in Persian miniature painting as researched by Dr. Alessandro Cancian, a Senior Research Associate at the Institute of Ismaili Studies, London,[23]

The Bottom Line is that Sufism is a mystical and spiritual tradition within Islam that emphasises the pursuit of a direct and personal experience of God through prayer, meditation, and other spiritual practices. Sufism is also known as Islamic mysticism or tasawwuf. The origins of Sufism are traced back to the teachings and practices of the Prophet Muhammad, PBUH, who is considered the first Sufi master. However, the formalisation of Sufism as a distinct tradition, within Islam began in the 8th and 9th centuries, in the Middle East, particularly in Iraq, Iran, and Syria. Some of the early Sufi masters include Hasan al-Basri, Rabia al-Adawiyya, and Al-Hallaj. The teachings of these early Sufis emphasized the importance of purifying the heart and seeking a direct experience of God, rather than simply following external rituals and laws. Over time, Sufism spread throughout the Muslim world, and different orders or tariqas emerged, each with their own practices and teachings. Some of the most prominent Sufi orders include the Qadiriyya, the Naqshbandiyya, and the Chishtiyya.

Sufism has also had a significant impact on the arts and literature of the Islamic world, with many poets and writers expressing spiritual themes and ideas through their work. Today, Sufism continues to be an important aspect of Islamic culture and spirituality, with millions of followers around the world.

Another important aspect of Sufism is gender equality, as there have been many female Sufi saints throughout history. Sufism is a mystical Islamic tradition that emphasizes the inner search for God, and it has been practiced by both men and women for centuries. Some well-known female Sufi saints include Rabia al-Adawiyya, a 8th century mystic from Basra, Iraq; Nizamuddin Auliya’s disciple, Bibi Sam, who is buried near his tomb in Delhi, India; and Fatima al-Nisaburiyya, a 12th century Persian Sufi who was known for her poetry and wisdom. There are many other examples of female Sufi saints throughout history, and their teachings and practices have had a significant impact on the development of the Sufi tradition, globally.

Sufism continues to have a significant impact in the 21st century, both within the Islamic world and beyond. Here are some of the ways in which Sufism is still relevant today:

- Spiritual guidance and personal transformation: Sufi teachings continue to offer spiritual guidance and practices for individuals seeking personal transformation and a deeper connection to the divine.

- Interfaith dialogue and understanding: Sufism’s emphasis on love, compassion, and unity has made it a valuable source of interfaith dialogue and understanding, particularly in a world where religious differences can lead to conflict and division.

- Social justice and activism: Sufis have historically been involved in social justice movements and activism, and many contemporary Sufi orders continue to promote social and environmental causes.

- Art and culture: Sufi poetry, music, and art have had a profound influence on Islamic and world culture, and continue to inspire artists and musicians around the globe.

- Counter-extremism: Some scholars believe that Sufism can play a role in countering extremism and radicalization, by offering a peaceful and tolerant interpretation of Islam that emphasizes the importance of compassion, humility, and service to others.

Overall, Sufism remains a vital and dynamic tradition in the 21st century, offering spiritual and practical guidance to individuals and communities around the world.

Sufism can assist in dissipating global belligerence in several ways:

- Emphasizing the Unity of Humanity: One of the central teachings of Sufism is the unity of all creation. Sufi teachings emphasize that all human beings are interconnected and that we should treat one another with respect and compassion. This teaching can help to break down barriers and promote understanding between people from different backgrounds.

- Promoting Tolerance and Non-Violence: Sufism teaches the importance of compassion, forgiveness, and non-violence. By promoting these values, Sufi teachings can help to counteract the aggressive and divisive rhetoric that can lead to conflict and war.

- Encouraging Dialogue and Understanding: Sufi teachings emphasize the importance of dialogue and understanding between people of different faiths and cultures. By promoting dialogue, Sufism can help to create a more peaceful and harmonious world.

- Fostering Spiritual Development: Sufi teachings emphasize the importance of spiritual development and self-awareness. By helping individuals to cultivate inner peace and wisdom, Sufism can promote a more peaceful and compassionate world.

- Offering a Counter-Narrative to Extremism: Some scholars believe that Sufism can serve as a counter-narrative to extremist ideologies. Sufi teachings emphasize the importance of love, compassion, and service to others, and can help to undermine the appeal of violent and intolerant ideologies, as Sufism is essentially a propagator of global Peace, in these turbulent times, currently experienced by humanoids

Without being prescriptive, prejudiced or biased, the author is of an opinion that Sufism can offer valuable philosophies, teachings and practices which can promote peace, understanding, and compassion in a world that is often marked by conflict, division, sectionalism, racism xenophobia and belligerence, which will ultimately destroy humanoids.

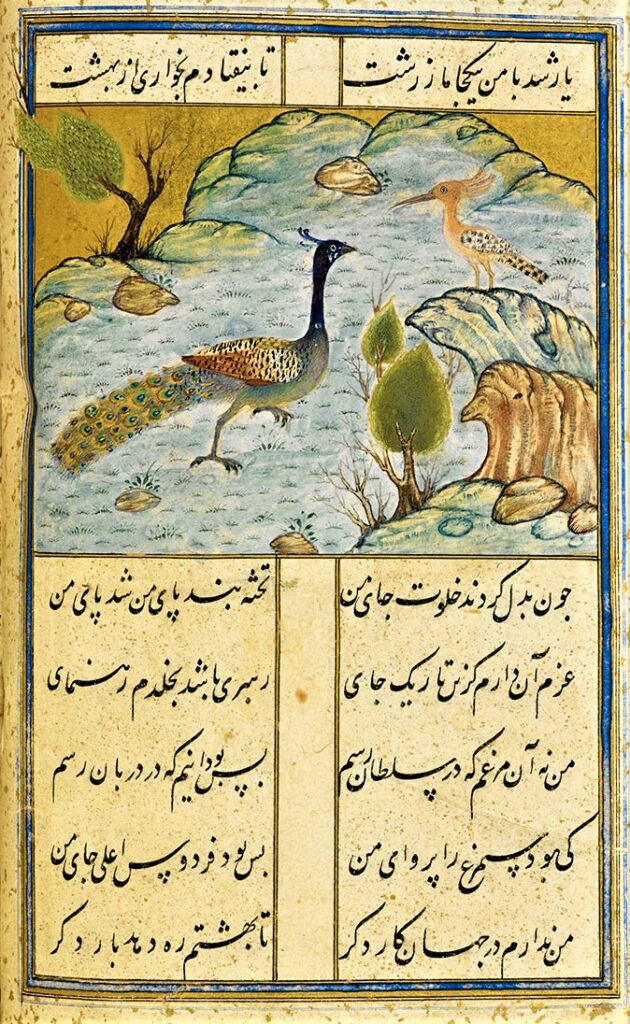

“The Pride of the Peacock” : A late Timurid copy of Mantiq al-tayr (‘The Conference of the birds’) by Farīd al-Dīn ʻAṭṭār. Depicted here is the vain peacock, who was banished from Paradise because of his pride.

(Photo credit: British Library)

References:

[1] Personal quote by author March 2023

[2] https://islam.stackexchange.com/questions/1/why-do-muslims-add-peace-be-upon-him-after-names-of-important-people

[3] https://www.bing.com/search?q=prophet+muhammad+full+name&cvid=28732c55de254f618c81e1662574fdcc&aqs=edge.4.0l9j69i11004.12880j0j1&pglt=41&FORM=ANNAB1&PC=U531

[4] https://www.islamicity.org/77864/sufism/

[5] https://www.islamicity.org/77864/sufism/#:~:text=of%20Muslim%20rulers%20and%20deeply%20influencing%20the%20religious%20thought%2C%20the%20arts%20and%20the%20literatures%20of%20those%20areas.

[6] https://www.transcend.org/tms/2021/11/the-foundation-of-peace-the-wisdom-of-mevlana-jalalud-din-muhammad-rumi/

[7] https://eurasianet.org/afghanistan-sufi-mysticism-makes-a-comeback-in-kabul

[8] https://doi.org/10.1080/0263493032000157717

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sufism_in_Afghanistan#:~:text=Lizzio%2C%20Ken%20(2003%2D06%2D01).%20%22Embodying%20history%3A%20a%20Naqshbandi%20shaikh%20of%20Afghanistan%22.%20Central%20Asian%20Survey.%2022%20(2%E2%80%933)%3A%20163%E2%80%93185.%20doi%3A10.1080/0263493032000157717.%20ISSN%C2%A00263%2D4937.%20S2CID%C2%A0143611860.

[10] McChesney, R. D. (2018-07-09). “Reliquary Sufism: Sacred Fiber in Afghanistan”. Sufism in Central Asia: 191–237. doi:10.1163/9789004373075_008. ISBN 9789004373075. S2CID 201494279.

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sufism_in_Afghanistan#:~:text=Azami%2C%20Dawood%20(2011%2D02%2D23).%20%22Sufism%20returns%20to%20Afghanistan%20after%20years%20of%20repression%22.%20BBC%20News.%20Retrieved%202020%2D06%2D26

[12] https://www.mpac.org/blog/updates/condemning-the-attack-in-kabul-on-mawlid-al-nabi.php

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sufism_in_Afghanistan#:~:text=McChesney%2C%20R.%20D.%20(2018%2D07%2D09).%20%22Reliquary%20Sufism%3A%20Sacred%20Fiber%20in%20Afghanistan%22.%20Sufism%20in%20Central%20Asia%3A%20191%E2%80%93237.%20doi%3A10.1163/9789004373075_008.%20ISBN%C2%A09789004373075.%20S2CID%C2%A0201494279.

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sufism_in_Afghanistan#:~:text=Khaama%2C%20News%20(18%20March%202020).%20%22Afghan%20women%20pilgrimage%20and%20their%20devoted%20beliefs%22.%20The%20Khaama%20Press%20News%20Agency.%20%7B%7Bcite%20news%7D%7D%3A

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mawlid

[16] https://www.rferl.org/a/Can_Sufis_Bring_Peace_to_Afghanistan/1503303.html

[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sufism_in_Afghanistan#:~:text=Brehmer%2C%20Marian%20(2015%2D03%2D25).%20%22Sufis%20in%20Afghanistan%3A%20The%20forgotten%20mystics%20of%20the%20Hindu%20Kush%22.%20Qantara.de%20%2D%20Dialogue%20with%20the%20Islamic%20World.%20Retrieved%202021%2D09%2D26

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hagiography#Islamic

[19] https://www.news18.com/news/lifestyle/muharram-the-importance-of-tazia-a-symbol-of-mourning-rituals-and-cultural-depiction-of-the-tragedy-of-karbala-4099226.html

[20] https://www.al-islam.org/media/story-imam-husayn#:~:text=Imam%20Husayn%20%28S%29%20is%20the%20grandson%20of%20Prophet,for%20refusing%20to%20side%20with%20a%20corrupt%20tyrant.

[21] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ibn_Arabi

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quran

[23] https://www.iis.ac.uk/our-people/units/qur-anic-studies/dr-alessandro-cancian/

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: Culture of Peace, Islam, Peace Culture, Peace art, Peacebuilding, Poetry, Religion, Rumi, Spirituality, Whirling Dervishes

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 13 Mar 2023.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Peace Propagators (Part 1): The Sufi Spiritual Masters, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.