Peace Propagators (Part 2): The Legacy of the Dead Poets

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 20 Mar 2023

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

Poetry has Propagated Peace, but the Heeders are Indeed a Rare Species, about to become Extinct[1]

Mirza Beg Asadullah Khan Poetic Couplet:

“Lest we forget: It is easy to be human, very hard to be humane.”

18 Mar 2023 – This publication discusses the contributions made by poets of the past to the propagation of peace philosophy, especially in the Indian subcontinent. While globally there have been millions of poets, composing their work in indigenous languages, these are often ignored by past imperialists occupation of their land and resultant erasure of their culture, traditions, as well as their creative and artistic talents. This was also the case of the destruction of the North American first nations, initially by the occupying British forces and then by the American migrants. This was a phenomenon wherever, the imperialists forces invaded a country ranging from Australia, New Zealand to the Far East, India and even South America.

This eradication of the indigenous culture and creative arts is particularly evident in the Indian peninsula, prior to the segregative partition in 1947, by the departing British forces, where they identified the religious differences between the Hindus and Muslims and employed the divide and rule principle of subjugation of the indigenous citizenry therein. The initial lack of acknowledgement and subsequent eradication of the Indian arts, including pillaging of religious artifacts, jewelry, as well as manuscripts, poetry and paintings by the British Raj, has not only denied the existence of a rich cultural heritage, an interesting an unique mix of Hindusm, Islam, Christianity as well as other religions, but also actively prevented its propagations as being subversive to the sustained subjugative rule of Imperial Britain which lasted nearly 200 long years and oppression of the Indians as a whole.

One such example is the poetry of Mirza Beg Asadullah Khan, commonly known by the name of Mirza Ghalib as a poets under the patronage of the last Mughal Emperor of India, Bahadur Shah Zafar, whose pathetic end was in a small prison cell in Rangoon Burman, after being placed in exile there by the British

Portrait of Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar 11 -1838 1857. The Patron of Mizra Ghalib inspiring Peace Poetry titled “The Grand Mughal of Delhi”

Painted by Josef August Schoefft in 1854

Mirza Beg Asadullah Khan (1797-1868), also known as Mirza Ghalib,[i] was an Indian poet.[ii] He was popularly known by the pen names Ghalib and Asad. His original Takhallus (pen-name) was Asad (meaning lion), drawn from his given name, Asadullah Khan. At some point early in his poetic career he also decided to adopt the pen-name of Ghalib (meaning all conquering, superior, most excellent).[iii] His honorific was Dabir-ul-Mulk, Najm-ud-Daula. During his lifetime, the already declining Mughal Empire was eclipsed and displaced by the British East India Company rule and finally deposed following the defeat of the Indian Rebellion of 1857; these are described through his work.[iv]

He wrote in both Urdu and Persian. Although his Persian Divan (body of work) is at least five times longer than his Urdu Divan, his fame rests on his poetry in Urdu. Today, Ghalib remains popular not only in the Indian subcontinent but also among the Hindustani diaspora, as well as amongst the Western arts, globally.[v]

Mirza Ghalib was born in Kala Mahal, Agra into[vi] a family of Mughals who moved to Samarkand (in modern-day Uzbekistan) after the downfall of the Seljuk kings. His paternal grandfather, Mirza Qoqan Baig, was a Seljuq Turk[vii] who had immigrated to India from Samarkand during the reign of Ahmad Shah (1748–54).[viii] He worked in Lahore, Delhi and Jaipur, was awarded the sub-district of Pahasu (Bulandshahr, UP) and finally settled in Agra, UP, India. He had four sons and three daughters.[ix]

Mirza Abdullah Baig (Ghalib’s father) married Izzat-ut-Nisa Begum, an ethnic Kashmiri,[x] and then lived at the house of his father-in-law, Ghalib’s grandfather. He was employed first by the Nawab of Lucknow and then the Nizam of Hyderabad, Deccan. He died in a battle in 1803 in Alwar and was buried at Rajgarh (Alwar, Rajasthan),[xi] when Ghalib was a little over 5 years old. He was then raised by his Uncle Mirza Nasrullah Baig Khan, but in 1806, Nasrullah fell off an elephant and died from related injuries.[xii]

In 1810, at the age of thirteen, Ghalib married Umrao Begum, daughter of Nawab Ilahi Bakhsh (brother of the Nawab of Ferozepur Jhirka).[xiii] He soon moved to Delhi, along with his younger brother, Mirza Yousuf, who had developed schizophrenia at a young age and later died in Delhi during the chaos of 1857.[xiv] None of his seven children survived beyond infancy. After his marriage, he settled in Delhi. In one of his letters, he describes his marriage as the second imprisonment after the initial confinement that was life itself. The idea that life is one continuous painful struggle that can end only when life itself ends, is a recurring theme in his poetry.

One of his couplets puts it in a nutshell:[16]

قید حیات و بند غم ، اصل میں دونوں ایک ہیں

موت سے پہلے آدمی غم سے نجات پائے کیوں؟The prison of life and the bondage of sorrow are the same

Why should man be free of sorrow before dying?

There are conflicting reports regarding his relationship with his wife. She was considered to be pious, conservative, and God-fearing.[i]

In 1850, Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar bestowed upon Mirza Ghalib the title of Dabir-ul-Mulk (Persian: دبیر الملک, lit. ’secretary of state’). The Emperor also added to it the additional title of Najm-ud-daula (Persian: نجم الدولہ, lit. ’star of the state’). The conferment of these titles was symbolic of Mirza Ghalib’s incorporation into the nobility of Delhi. He also received the title of Mirza Nosha (Persian: مرزا نوشہ) from the Emperor, thus enabling him to add Mirza to his name. He was also an important courtier of the royal court of the Emperor. As the Emperor was himself a poet, Mirza Ghalib was appointed as his poet tutor in 1854. He was also appointed as a tutor of Prince Fakhr-ud Din Mirza, eldest son of Bahadur Shah II, (d. 10 July 1856). He was also appointed by the Emperor as the royal historian of the Mughal Court.[ii]

Being a member of declining Mughal nobility and old landed aristocracy, he never worked for a livelihood, lived on either royal patronage of Mughal Emperors, credit, or the generosity of his friends. His fame came to him posthumously. He had himself remarked during his lifetime that he would be recognized by later generations. After the decline of the Mughal Empire and the rise of the British Raj, despite his many attempts, Ghalib could never get the full pension restored.

Literary career of Ghalib commenced when he started composing poetry at the age of 11. His first language was Urdu, but Persian and Turkish were also spoken at home. He received an education in Persian and Arabic at a young age. During Ghalib’s period, the words “Hindi” and Urdu” were synonyms (see Hindi–Urdu controversy). Ghalib wrote in Perso-Arabic script which is used to write modern Urdu, but often called his language “Hindi”; one of his works was titled Ode-e-Hindi (Urdu: عود هندی, lit. ’Perfume of Hindi’).[iii] When Ghalib was 14 years old a newly converted Muslim tourist from Iran (Abdus Samad, originally named Hormuzd, a Zoroastrian) came to Agra.[iv] He stayed at Ghalib’s home for two years and taught him Persian, Arabic, philosophy, and logic.[v]

Ghalib wrote poem in Nastaliq[vi], as well. also romanized as Nastaʿlīq or Nastaleeq is one of the main calligraphic hands used to write the Perso-Arabic script in the Persian and Urdu languages, often used also for Ottoman Turkish poetry, rarely for Arabic. Nastaliq developed in Iran from naskh beginning in the 13th century[vii],[viii] and remains very widely used in Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan. It is also used in India as a minority script and other countries for written poetry and as a form of art.[ix] Although Ghalib valued Persian over Urdu,[x] his fame rests on his writings in Urdu. Numerous commentaries on Ghalib’s ghazal compilations have been written by Urdu scholars. The first such elucidation or Sharh was written by Ali Haider Nazm Tabatabai of Hyderabad during the rule of the last Nizam of Hyderabad. Before Ghalib, the ghazal was primarily an expression of anguished love; but Ghalib expressed philosophy, the travails, and mysteries of life and wrote ghazals on many other subjects, vastly expanding the scope of the ghazal. In keeping with the conventions of the classical ghazal, in most of Ghalib’s verses, the identity and the gender of the beloved are indeterminate. The critic/poet/writer Shamsur Rahman Faruqui explains[xi] that the convention of having the “idea” of a lover or beloved instead of an actual lover/beloved freed the poet-protagonist-lover from the demands of realism. Love poetry in Urdu from the last quarter of the seventeenth century onwards consists mostly of “poems about love” and not “love poems” in the Western sense of the term. The first complete English translation of Ghalib’s ghazals was Love Sonnets of Ghalib, written by Sarfaraz K. Niazi[xii] and published by Rupa & Co in India and Ferozsons in Pakistan. It contains complete Roman transliteration, explication, and an extensive lexicon.[xiii]

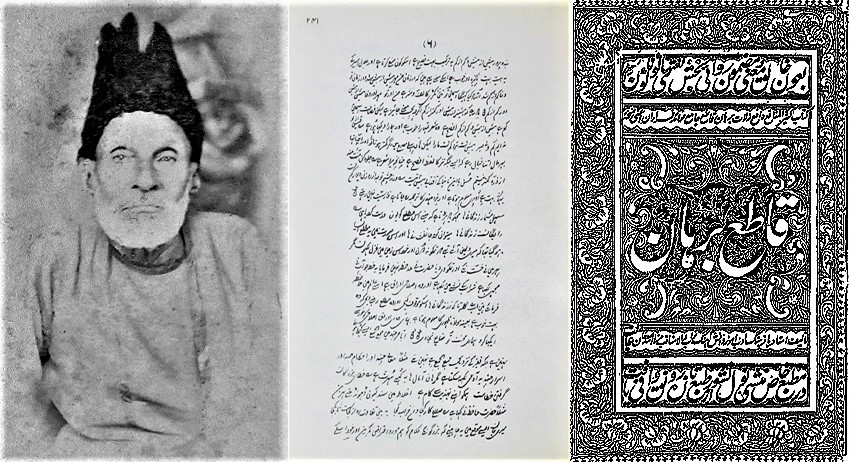

Left: Mizra Ghalib in 1868 when he no longer had his patronage, nor his pension.

Middle: A page from Ghalib’s letters in Urdu, in his own handwriting.

Right: The Cover Page of Ghalib’s Persian Manuscript, Qaat’i-e Burhaan

Archival Photographs

The question is how can community peace be achieved through poetry in Urdu language. Poetry has always been a powerful tool to promote peace and harmony in communities, and the Urdu language, with its rich literary tradition, is no exception. Here are some ways in which community peace can be achieved through poetry in Urdu:

- Celebrate diversity: Urdu poetry can be used to celebrate the diverse cultural and linguistic traditions that make up a community. By highlighting the commonalities that bind people together, poetry can help promote a sense of unity and understanding.

- Promote dialogue: Poetry can be used to encourage dialogue and discussion among members of a community. By presenting different perspectives and viewpoints, poetry can help foster empathy and mutual respect, even in the face of differences.

- Address social issues: Urdu poetry can be used to address social issues that are causing tension and conflict in a community. By giving voice to the marginalized and the oppressed, poetry can help raise awareness and create a sense of urgency around issues such as poverty, inequality, and discrimination.

- Foster creativity and self-expression: Poetry can be a powerful tool for fostering creativity and self-expression, which can in turn help build a sense of community and belonging. By providing a platform for people to share their thoughts and feelings, poetry can help build connections and promote understanding.

- Promote nonviolence: Finally, Urdu poetry can be used to promote nonviolence and peaceful conflict resolution. By emphasizing the importance of compassion, understanding, and forgiveness, poetry can help create a culture of peace and mutual respect in a community.

Ghalib’s Urdu poetry also has commonality with other language poetry, particularly with other languages of the Indian subcontinent. Urdu is itself a blend of several languages including Persian, Arabic, and Hindi, and its poetry reflects this rich cultural heritage. One of the commonalities between Urdu poetry and poetry in other languages is the use of metaphors and symbolism. Poets in many languages use imagery and metaphor to express complex emotions and ideas in a way that is more vivid and memorable than plain language. Another commonality is the use of rhyme and meter. Many languages have poetic traditions that rely on specific rhyme schemes or rhythmic patterns, which can help to create a sense of musicality and flow in the poetry. In addition, poetry in many languages often deals with universal themes such as peace, love, loss, longing, and the search for meaning in life. While the specific cultural context and historical background may vary, these themes are often shared across different languages and cultures. Urdu poetry has its own unique characteristics and traditions, it is also part of a larger global poetic tradition that shares many commonalities across different languages and cultures. These unique attributes are found in the poetry of Ghalib.

There have been many great poets in the history of Urdu language, but one of the most renowned and beloved Urdu poets is Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, who lived in the 19th century, is widely regarded as one of the greatest poets of the Urdu language. His poetry is known for its depth, complexity, and rich imagery, and has been celebrated for its ability to capture the human experience with great sensitivity and insight. Ghalib’s work covers a wide range of themes, including peace, , loss, mortality, and the search for meaning in life. His use of language is masterful, and he is often cited as a major influence on subsequent generations of Urdu poets. Ghalib’s poetry remains popular and influential to this day, and his work has been translated into many different languages. He is revered not only for his literary achievements, but also for his contributions to the development of Urdu language and culture.

The differences between Urdu and Persian poetry while they share many similarities, as both languages have a rich literary tradition and have influenced each other over the centuries. However, there are also some differences between the two that are worth noting:

- Language: Urdu and Persian are different languages with distinct grammatical structures and vocabularies. While there are many common words and phrases between the two languages, the syntax and grammatical rules differ. Urdu has a more Arabic and Hindi influence, while Persian has a more pure Indo-European language structure.

- Cultural Context: While both Urdu and Persian poetry deal with universal themes such as love, nature, and spirituality, they also reflect the cultural context in which they were written. Persian poetry is often associated with the rich cultural and literary heritage of Iran, while Urdu poetry has its roots in the Indian subcontinent.

- Meter and Rhyme Scheme: While both Urdu and Persian poetry often use meter and rhyme scheme, the specific patterns used are different. Persian poetry has a more complex and formal structure, while Urdu poetry tends to be more flexible in terms of meter and rhyme. Meter and scheme are two important elements of poetry that help create a sense of rhythm, flow, and musicality in the language. Meter refers to the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line of poetry. Each unit of meter is called a foot, and different types of feet can be combined to create a specific meter or rhythm. For example, iambic pentameter is a meter in which each line contains five iambs, which are pairs of unstressed and stressed syllables. Meter is important because it creates a sense of structure and order in a poem and can help reinforce the meaning and emotional impact of the words. Rhyme scheme, on the other hand, refers to the pattern of rhyming words at the end of each line in a poem. In a rhyming poem, each line typically ends with a word that sounds similar to the word at the end of the preceding line. The pattern of rhymes is often indicated by a series of letters, with each letter representing a different rhyme sound. For example, an ABAB rhyme scheme would indicate that the first and third lines of each stanza rhyme with each other, and the second- and fourth-lines rhyme with each other. Rhyme scheme is important because it creates a sense of unity and coherence in a poem, tying together different lines and stanzas and creating a musical effect that can be pleasing to the ear. However, not all poems use rhyme scheme, and other poetic techniques such as alliteration, assonance, and repetition can also create a sense of musicality and rhythm in the language. Mirza Ghalib was an expert in creating meter and rhyme in his poetry. He was a master of the Urdu language and its poetic traditions, and his poetry reflects a deep understanding of the technical aspects of the craft. Ghalib’s poetry is known for its complex and nuanced use of language, as well as its mastery of meter and rhyme. He was particularly skilled at using the ghazal form, which is a type of poetry that uses a specific rhyme scheme and meter to create a musical effect. Ghalib’s ghazals often feature intricate rhyme schemes and subtle variations in meter that add to the beauty and richness of his poetry. In addition to his technical skill, Ghalib was also a master of poetic expression and emotion. His poetry deals with a wide range of themes, from love and loss to the nature of existence and the search for meaning in life. Through his words, he was able to capture the complexity and depth of human experience in a way that remains powerful and resonant to this day.

- Themes: Persian poetry is often associated with mysticism, spiritualism, and the beauty of nature. Urdu poetry, on the other hand, often deals with the complexities of human relationships, social and political issues, peace, belligerence and everyday life. However, these themes are not exclusive to one language and are common to many poets in both languages.

Essentially, while there are differences between Urdu and Persian poetry, both have a rich and vibrant poetic tradition that has been shaped by their unique cultural contexts and histro-political development.

Ghalib’s poetry is often noted for its use of double meanings, irony, and wordplay, which give it a layered and complex quality. Ghalib’s poetry often contains multiple meanings and interpretations, and he was skilled at using language in a way that allowed readers to engage with his work on multiple levels. He was particularly known for his use of metaphors and symbols, which could be interpreted in different ways depending on the context and the reader’s perspective. This complexity of meaning is one of the reasons why Ghalib’s poetry remains so widely read and celebrated. His words are able to evoke a range of emotions and ideas, and his work continues to be studied and analyzed by scholars and poetry lovers around the world.

Examples of duality in meaning of Ghalib’s poetry, based on a couplet by Ghalib that demonstrates his use of duality in meaning:

“Har ek baat pe kehte ho tum ki tu kya hai, Tumhi kaho ke ye andaaz-e-guftgu kya hai”

This couplet can be translated as:

“You ask me what I am on every single occasion,

Tell me, what kind of conversational style is this?”

At face value, the couplet seems to be a simple response to someone who is constantly questioning and probing the speaker’s identity. However, upon closer examination, the couplet can also be seen as a commentary on the art of conversation itself. By asking “what kind of conversational style is this?”, Ghalib is suggesting that the other person’s persistent questioning is not conducive to genuine conversation or meaningful exchange of ideas.

In this way, the couplet can be interpreted on multiple levels, as a response to a specific situation, as well as a broader commentary on the nature of human communication. This use of double meanings and multiple interpretations is a hallmark of Ghalib’s poetry, and is one of the reasons why his work remains so influential and celebrated. There are also concealed messages or hidden meanings in Ghalib’s work, which can be interpreted in different ways. Here are a few examples:

“Yeh na thi hamari qismat ki visaal-e-yaar hota, Agar aur jeete rahte yahi intezaar hota”

This couplet can be translated as:

“It was not in my fate to be united with my beloved,

Even if I had lived longer, I would have still been waiting.”

On the surface, this couplet appears to be a simple expression of the speaker’s lament that they were unable to be with their beloved. However, upon closer examination, the couplet can also be seen as a commentary on the nature of human desire and the futility of waiting for something that may never come. By saying “even if I had lived longer, I would have still been waiting,” Ghalib is suggesting that the human longing for connection and love can never truly be fulfilled.

“Dil hi to hai na sang-o-khisht dard se bhar na aaye kyun, Royenge hum hazaar baar koi hamein sataaye kyun”

This couplet can be translated as:

“Is it not the heart that is filled with pain, not the stone or brick,

Why then does it not overflow with tears, why must someone else torment us?”

At first reading, this couplet seems to be a simple expression of the speaker’s sorrow and frustration. However, upon closer examination, the couplet can also be seen as a commentary on the nature of human suffering and the tendency to blame others for our pain. By saying “why must someone else torment us?”, Ghalib is suggesting that the root of our suffering lies within ourselves, and that we must take responsibility for our own emotions and reactions.

These examples demonstrate how Ghalib’s work often contains hidden meanings and deeper insights that can be interpreted in different ways, depending on the reader’s perspective and understanding. His poetry continues to be studied and celebrated for its complexity, richness, and beauty. Furthermore, there is no specific mention of Ghalib’s wife or mistress in the couplets I mentioned earlier. Both couplets are more broadly about the nature of human desire, love, and suffering, and do not refer to any specific person or relationship. However, Ghalib did have a complicated personal life, and his poetry often reflects his own experiences and emotions. Many of his poems do touch on themes of love, loss, and longing, and it is possible that some of his work was inspired by his relationships with women in his life. Albeit, it is important to approach Ghalib’s work as a work of art in its own right, rather than simply as a reflection of his personal life. His poetry is complex, multilayered, and speaks to universal themes and emotions that transcend any specific context or relationship.

Ghalib’s poetry was influenced and inspired by a number of poets who came before him, as well as by the political and cultural climate of his time. Some of the major figures who inspired his generation of poetry include:

- Mir Taqi Mir: Ghalib considered Mir Taqi Mir to be one of his greatest influences. Mir was a leading poet of the 18th century and is considered to be one of the pioneers of Urdu poetry. His work was known for its elegance, simplicity, and emotional depth.

- Meer Dard: Meer Dard was another prominent poet of the 18th century and was known for his spiritual and romantic poetry. Ghalib was particularly inspired by his Sufi poetry, which explored themes of love, devotion, and the divine.

- Sauda: Sauda was a poet of the 18th century who was known for his satirical and humorous poetry. Ghalib was inspired by his wit and his ability to use language to convey a range of emotions and ideas.

- Zauq: Zauq was a poet and a courtier in the Mughal court. He was known for his skillful use of language and his ability to compose poetry in a wide range of styles and genres. Ghalib considered him to be one of his most important mentors and sources of inspiration.

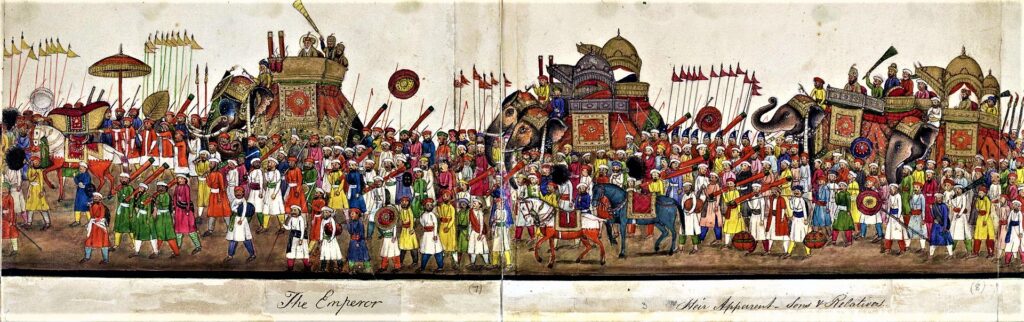

These poets, along with others, helped to shape the literary landscape of Ghalib’s time and provided a rich source of inspiration for his own work. Furthermore, Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal emperor of India, was a major inspiration for Ghalib. Bahadur Shah Zafar was a poet himself and was known for his patronage of the arts. He was also a contemporary of Ghalib and lived in the same historical and cultural context. Ghalib was a frequent visitor to the Mughal court and was known to have a close relationship with Bahadur Shah Zafar. Ghalib dedicated a number of his poems to the emperor and even composed a eulogy for him after his death.

Bahadur Shah Zafar’s patronage of the arts helped to create a vibrant literary and artistic scene in Delhi, and Ghalib was one of the major figures who emerged from this milieu. He was deeply influenced by the emperor’s love of poetry and his dedication to preserving the cultural traditions of the Mughal court.

In his poetry, Ghalib often celebrated the cultural richness of Delhi and the legacy of the Mughal emperors, including Bahadur Shah Zafar. He was particularly drawn to the themes of nostalgia, peace, harmony and loss that were associated with the decline of the Mughal empire, and his work often reflects a sense of longing for a bygone era of cultural and artistic flourishing. The reasons for a Mughal Emperor to be a patron of Ghalib, when he had an entire empire and the British to worry about, more importantly, were, that Bahadur Shah Zafar was not only the Mughal emperor, but also a renowned poet and patron of the arts. He was known for his deep appreciation of literature, music, and the visual arts, and he saw himself as a custodian of the cultural traditions of the Mughal court. In this context, his patronage of Ghalib and other poets can be seen as part of his broader efforts to promote and preserve the artistic and cultural heritage of the Mughal empire. In addition to this cultural dimension, there were also political reasons for Bahadur Shah Zafar to patronize poets like Ghalib.

The Mughal court was a complex web of alliances, rivalries, and factions, and poets played an important role in navigating these intricate political dynamics. By patronizing poets like Ghalib, Bahadur Shah Zafar was able to cultivate relationships with powerful figures in the literary and cultural worlds, and to use these relationships to advance his political agenda. Finally, the role of the Mughal emperor in the 19th century was largely ceremonial, as the British had taken over political power in India. As a result, Bahadur Shah Zafar had more time and resources to devote to cultural pursuits, and his patronage of the arts can be seen as a way to maintain his status and prestige in a time of political decline. There were certainly many factors that contributed to the decline and eventual downfall of the Mughal empire, and the role of Bahadur Shah Zafar in this process is a matter of historical debate.

A panorama showing the Royal Mughal opulence and procession to celebrate the feast of the Eid ul-Fitr, with the emperor on the elephant to the left and his sons to the right (24 October 1843). On some such parades, Mizra Ghalib was also in the procession.

On the one hand, it is true that Bahadur Shah Zafar was known for his love of poetry, music, and other artistic pursuits, and he was often criticized for spending too much time and resources on these activities. Some historians argue that his preoccupation with cultural pursuits left him ill-prepared to deal with the political and military challenges of his time, including the threat posed by the British colonial forces. On the other hand, it is important to recognize that the decline of the Mughal empire was not solely the result of Bahadur Shah Zafar’s personal choices and actions. There were a variety of political, economic, and social factors that contributed to the empire’s decline, including internal conflicts, external invasions, and the rise of regional powers. Furthermore, Bahadur Shah Zafar was not simply a passive observer of these events. He was a complex and multifaceted figure who was deeply engaged in the political and cultural life of his time, and he played an important role in shaping the Mughal court and its cultural legacy.

In the final analysis, the decline of the Mughal empire was a complex and multifaceted process that cannot be reduced to any one cause or factor. While Bahadur Shah Zafar’s love of poetry, peace and the arts may have contributed to his reputation as a less-than-adept ruler, it is important to recognise that he was a multifaceted figure who played an important role in shaping the cultural and political landscape of his time. Some authors attribute the decline of the Mughal Empire was due to the emperors wasting their life on wine women and song, literally. However, the decline of the Mughal Empire was a complex and multifaceted process that cannot be attributed to any single factor. While it is true that some Mughal emperors, including Bahadur Shah Zafar, were known for their love of poetry, music, and other cultural pursuits, it is important to recognize that there were many other factors that contributed to the empire’s decline. One of the key factors was the weakening of the central authority of the Mughal state, which led to the rise of powerful regional states and the loss of effective control over large parts of the empire. This was due in part to internal conflicts and power struggles among Mughal nobles and factions, as well as external threats from rival powers such as the Marathas and the British. Economic factors also played a role in the decline of the Mughal Empire. The increasing costs of maintaining a large and complex empire, combined with the decline of traditional revenue sources such as agriculture, led to financial instability and an inability to fund military campaigns and other essential activities.

Finally, it is important to recognize that the decline of the Mughal Empire was also influenced by broader global trends, including the rise of European colonial powers and the emergence of new trade networks and economic systems. These factors contributed to the erosion of Mughal power and influence, and ultimately led to the downfall of the empire. The decline of the Mughal Empire is generally considered to have begun in the late 17th century during the reign of Aurangzeb Alamgir, the sixth Mughal Emperor. While his reign saw significant territorial expansion and military conquests, it also witnessed growing social and political unrest, as well as the increasing influence of regional powers and the decline of the Mughal court. Aurangzeb’s strict policies towards religious minorities, particularly Hindus, also contributed to growing social tensions and political instability within the empire. His reign was marked by conflict and rebellion, including the prolonged Deccan Wars and the Sikh and Jat uprisings.

After Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, the Mughal Empire was plagued by a series of weak and ineffective rulers who were unable to maintain the empire’s territorial integrity or confront the growing threats posed by regional powers such as the Marathas and the British. By the mid-18th century, the Mughal Empire had become a shadow of its former self, and it was ultimately conquered and dissolved by the British in the 19th century. The proverbial last straw that led to the dissolution of the Mughal Empire was the Indian Rebellion of 1857, also known as the First War of Indian Independence. This was a major uprising against British colonial rule that was sparked by a variety of factors, including economic grievances, religious tensions, and cultural conflicts. The rebellion began in May 1857 in the town of Meerut and quickly spread throughout northern India, drawing support from a wide range of social and political groups. The Mughal Emperor at the time, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was declared the leader of the rebellion and played a symbolic role in the movement, although his authority was largely ceremonial.

Despite initial successes, the rebellion was eventually suppressed by the British, who saw it as a threat to their colonial interests in India. The British exiled Bahadur Shah Zafar to Burma, effectively ending the Mughal Empire and consolidating British control over India. While the Indian Rebellion of 1857 was not the only factor that contributed to the dissolution of the Mughal Empire, it is often seen as a pivotal moment in Indian history and a key turning point in the struggle for independence from colonial rule.

In the midst of this political turmoil and eventual expropriation of India by the British Raj, Mirza Ghalib composed couplets on harmony and peace. Here are a few couplets on harmony and peace by Mirza Ghalib:

“Har ek baat pe kehte ho tum ki tu kya hai, Tumhi kaho ki yeh andaaz-e-guftgoo kya hai”

English Translation:

“On every topic you question who you are, tell me what kind of conversation style is this?”

This couplet highlights the importance of having meaningful and peaceful conversations. It suggests that instead of focusing on who is right or wrong, we should focus on having constructive dialogue.

“Hain aur bhi duniya mein sukhanevar bahut achhe, Kahte hain ki Ghalib ka hai andaaz-e-bayaan aur”

English Translation:

“There are many skilled poets in the world, but they say that Ghalib has a unique style of expression.”

This couplet emphasizes the importance of diversity and acceptance of different cultures and perspectives. It suggests that there are many ways to express oneself, and we should appreciate and learn from each other’s unique styles.

“Hai Bas Ki Har Ek Unke Ishq Mein Mashgul, Tujhko Din Raat, Maujood Hai Yaaro.”

Translation:

“Every breath of mine is dedicated to love, my friends, day and night.”

This couplet highlights the importance of love and compassion in creating harmony and peace. It suggests that if we all focused on spreading love and positivity, the world would be a much more peaceful place.

Here are a few couplets by Mirza Ghalib on the theme of peace:

“Aah ko chaahiye ik umr asar hone tak, Kaun jiitaa hai tere zulf ke sar hone tak”

Translation:

“Sighs must persist till they have an effect, who could live until your hair graces their neck”

This couplet suggests that peace and harmony can only be achieved through perseverance and patience. It implies that we should continue to work towards peace even if it takes a lifetime to achieve it.

“Jo tha khwab sa, kya kahen ke sach tha kya hai,

Khoob khayaal-e-tanhai main jalva numayaan ho gaya”

Translation:

“What can one say of that dreamlike state, was it real or not?

In the beauty of solitude, it became manifest.”

This couplet highlights the idea that peace and harmony can be found within oneself, and that sometimes solitude can be a powerful tool for finding inner peace.

“Main kahoon aur woh muskura dey,

Main jawaab-e-shikwa nahin”

Translation:

“I speak and it smiles back,

it doesn’t answer my complaints.”

This couplet suggests that peace and harmony can be found in acceptance and forgiveness. It implies that instead of dwelling on grievances, we should focus on finding ways to move forward and find peace.

The Bottom line is Ghalib placed a greater emphasis on seeking of God rather than ritualistic religious practices; although he followed Shia theology and had said many verses in praise of Alī ibn Abī Ṭālib.[i] Ghalib states:

ہے پرے سرحد ادراک سے اپنا مسجود

قبلے کو اہل نظر قبلہ نما کہتے ہیں

The object of my worship lies beyond perception’s reach;

For men who see, the qibla is a compass, nothing more.[ii]

He staunchly disdained the practices of certain Ulema, who in his poems represent narrow-mindedness and hypocrisy.[iii]

Mirza Ghalib, the famous Urdu and Persian poet, passed away on February 15, 1869. He is buried in Hazrat Nizamuddin near the tomb of Nizamuddin Auliya. Mirza Ghalib’s Mausoleum is located in Delhi, India. The following is the inscription on the tombstone at his grave:

“तू उड़ जाए तेरी लिखी हुई ताक़दीर रहे

तेरा सफ़र तो कुछ इस तरह से गुज़रे“

Translation:

“Even if you fly away, your written destiny remains

May your journey pass like this.”

This couplet was penned by Ghalib himself and reflects his philosophy of acceptance of fate and detachment from worldly attachments.

During the anti-British Rebellion in Delhi on 5 October 1857, three weeks after the British troops had entered through Kashmiri Gate, some soldiers climbed into Ghalib’s neighbourhood and hauled him off to Colonel Brown for questioning.[iv] He appeared in front of the colonel wearing a Central Asian Turkic style headdress. The colonel, bemused at his appearance, inquired in broken Urdu, “Well? You Muslim?”, to which Ghalib replied sardonically, “Half?” The colonel asked, “What does that mean?” In response, Ghalib said, “I drink wine, but I don’t eat pork.”[v]

A large part of Ghalib’s poetry focuses on the Naʽat, poems in praise of Prophet Muhammad PBUH, which indicates that Ghalib was a devout Muslim. Ghalib wrote his Abr-i gauharbar The Jewel-carrying Cloud’) as a Naʽat poem. Ghalib also wrote a qasida of 101 verses in dedication to a Naʽat. Ghalib described himself as a sinner who should be silent before Prophet Muhammad PBUH, as he was not worthy of addressing him, who was praised by God.[vi]

Mirza Ghalib’s legacy has endured for over two centuries and continues to be relevant in the 21st century. Here are a few aspects of his legacy that are particularly relevant:

- Literary Influence: Ghalib’s poetry continues to inspire and influence poets, writers, and scholars around the world. His mastery of language, wit, and depth of thought make his poetry timeless and universal.

- Cultural Significance: Ghalib’s works are an integral part of the cultural heritage of India and Pakistan. His poetry reflects the social, political, and cultural milieu of the time, making it an important source of historical and cultural knowledge.

- Philosophical Insights: Ghalib’s poetry is not only aesthetically pleasing but also offers profound philosophical insights. His poetry reflects a deep understanding of the human condition and offers a unique perspective on life, love, and spirituality.

- Cross-Cultural Appeal: Ghalib’s poetry has transcended cultural and linguistic barriers and has been translated into several languages, including English, French, Spanish, and German. This has helped to introduce his works to a wider audience and has contributed to his enduring legacy and indirectly effect peaceful coexistence in the multicultural India and the world.

Mirza Ghalib’s legacy, as a dead poet from India, in the 21stcentury is multidimensional and continues to evolve, as his works are rediscovered and reinterpreted by new generations of younger readers and scholars, across all religions and social strata. Hence his legacy will encourage the progressive evolution of peace and harmony, globally.

Main Picture: Mizra Ghalib’s tomb near Chausath Khamba, Nizamuddin area Delhi, India

Inset top: Inscription in Mirza Ghalib’s Mausoleum

Inset Bottom: The actual grave of Mizra Ghalib with tombstone and covered with green cloth, inside the Mausoleum

References:

[1] Personal quote by the author, March 2023.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghalib#:~:text=Pavan%20K.%20Varma%20(1989).%20Ghalib%2C%20The%20Man%2C%20The%20Times.%20New%20Delhi%3A%20Penguin%20Books.%20p.%C2%A086.%20ISBN%C2%A00%2D14%2D011664%2D8.

[3]https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mirza-Asadullah-Khan-Ghalib

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghalib#:~:text=Pauwels%2C%20Heidi%20R.M.%20(2007).%20Indian%20Literature%20and%20Popular%20Cinema%3A%20Recasting%20Classics%20%E3%80%8B%20From%20ghazal%20to%20film%20music.%20Routledge.%20p.%C2%A0153.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D11%2D34%2D06255%2D3.

[5] http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/bombay-times/remembering-1857-in-2007/articleshow/2035354.cms

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghalib#:~:text=Ras%20H.%20Siddiqui%20(27%20July%202003).%20%22Ghalib%20in%20California%22.%20Dawn.%20Archived%20from%20the%20original%20on%204%20February%202009.%20Retrieved%2020%20May%202013.

[7] https://web.archive.org/web/20140101100342/http://m.ibnlive.com/news/no-memorial-for-ghalib-at-his-birthplace-agra/441946-3-242.html

[8] https://www.rekhta.org/ebooks/ghalib-ki-aap-beeti-ebooks?lang=ur

[9] https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ahmad-Shah-Mughal-emperor

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghalib#:~:text=Imam%2C%20Mir%20Jaffar%3B%20Imam%20(2003).%20Mirza%20Ghalib%20and%20the%20Mirs%20of%20Gujarat.%20Gujarat%2C%20India%3A%20Rupa%20Publications.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D8

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghalib#:~:text=Mirza%20Asadullah%20Khan%20Ghalib%20(2000).%20Persian%20poetry%20of%20Mirza%20Ghalib.%20Pen%20Productions.%20p.%C2%A07.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D81%2D87581%2D00%2D0.

[12] https://web.archive.org/web/20121103215537/http://www.megajoin.com/video/p01eCmEYmYI/mirza-ghalib-kahoon-jo-haal-ch-atma

[13] Spear, Percival (1972). “Ghalib’s Delhi” (PDF). columbia.edu. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

[14] https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/galib-mirza-esedullah

[15] https://web.archive.org/web/20121103215537/http://www.megajoin.com/video/p01eCmEYmYI/mirza-ghalib-kahoon-jo-haal-ch-atma

[16] https://web.archive.org/web/20130518090200/http://www.sufism.ru/eng/txts/a_godless.htm

[17] http://www.uq.net.au/~zzhsoszy/ips/l/loharu.html

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghalib#:~:text=Pavan%20K.%20Varma%20(1989).%20Ghalib%2C%20The%20Man%2C%20The%20Times.%20New%20Delhi%3A%20Penguin%20Books.%20p.%C2%A086.%20ISBN%C2%A00%2D14%2D011664%2D8.

[19] https://books.google.com/books?id=tqB3PgAACAAJ

[20] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources/978-0-14306-481-7

[21] https://web.archive.org/web/20121103215537/http://www.megajoin.com/video/p01eCmEYmYI/mirza-ghalib-kahoon-jo-haal-ch-atma

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nastaliq

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nastaliq#CITEREFBlair

[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Gholam-Hosayn_Yusofi&action=edit&redlink=1

[25] https://www.tug.org/TUGboat/tb29-1/tb91gulzar.pdf

[26] https://books.google.com/books?id=pJJPtIiQCD0C

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghalib#:~:text=%22Shamsur%20Rahman%20Faruqui%20explains%22%20(PDF).%20Columbia%20University.

[28] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghalib#:~:text=%22Dr.%20Sarfaraz%20K.%20Niazi%22.%20niazi.com.

[29] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghalib#:~:text=Roman%20transliterations%20with%20English%20translation%20of%20uncommon%20words

[30] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghalib#:~:text=%22Mirza%20Ghalib%3A%20A%20Liberal%20Poet%22.%20Pixstory.%20Retrieved%2017%20November%202022.

[31] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources/978-1-4088-0092-8

[32] Sabri, Zahra (3 December 2016). “Three Shi’a Poets: Sect-Related Themes in Pre-Modern Urdu Poetry”. Indian Ocean World Centre Working Paper Series (2). ISSN 2371-5111.

[33] William Dalrymple (2009). The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi, 1857. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4088-0092-8.

[34] “Appendix 2. Ghalib Concordance, with Standard Divan Numbers”, Ghalib, Columbia University Press, pp. 115–120, 31 December 2017, doi:10.7312/ghal18206-008, ISBN 9780231544009, retrieved 17 November 2022

[35] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghalib#:~:text=Annemarie%20Schimmel%20(1985).%20And%20Muhammad%20is%20His%20Messenger%20%E2%80%93%20The%20Veneration%20of%20the%20Prophet%20in%20Islamic%20Piety.%20University%20of%20North%20Carolina%20Press.%20p.%C2%A0115.%20ISBN%C2%A09780807841280.

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: Culture of Peace, Peace Culture, Peace art, Peacebuilding, Poetry, Religion, Spirituality

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 20 Mar 2023.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Peace Propagators (Part 2): The Legacy of the Dead Poets, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.