Rethinking Conflict: The Cultural Approach

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER, 12 Aug 2024

Prof. Johan Galtung - TRANSCEND Media Service

Prepared for the Intercultural Dialogue and Conflict Prevention Project

Council of Europe, 2002

1. Conflict and Violence

A minimum of concepts is indispensable even if it is a reader’s human right to come quickly to the substance.

Conflict is a complex human phenomenon and should by no means be confused with violence. Violence is to harm and hurt the body, mind and/or spirit of someone, including Self; by verbal and/or physical means, including body language. Violence leaves behind trauma, those traces – very difficult to remove, often indelible – on body, mind and spirit. Violence is an expression of contempt and hatred – “lack of respect” to put it mildly – and to be violated is an experience of humiliation. The harm and hurt of the mind and the spirit may leave behind the most important trauma. When shared with others, particularly the bereaved, in the same nation, we can talk about a collective trauma, raw material for a national culture of revenge/revanche.

In many cultures of violence trauma has a twin concept: the glory of having “won” by inflicting violence, raw material for a national culture of triumphalism. The word “war” – a series of “battles”, today “operations”, with glory as “victory” and trauma as “defeat” – is used, not ”violence”. But “violence”, violation, conveys better the cruelty of the perpetrator and the suffering of the victim, and how violence breeds violence through the revanchism of trauma and the triumphalism of glory.

Although conflicts may lead to violence they are totally different conceptually. At the core of a conflict, the root of a conflict there is always an incompatibility, a contradiction, between goals. Like “I want X, you want X, and we cannot have it both”. Conflict is as normal as the air around us. Talk about “conflict prevention” is nonsense. Violence is what has to be prevented.

A goal is a state of affairs (“I now possess X”), with a value attached to it. A value is something to be pursued (positive goal) and/or to be avoided (negative goal). In either case conflict is always emotional. Values are backed by emotion. But in a conflict there is also a lot of cognition. Things are described, incessantly. In border conflicts like Kashmir, or Israel/Palestine, descriptions and prescriptions abound. Again, all this is natural, normal. The question is how we handle it.

Thus, there is no law of nature saying that a conflict has to move from a Phase I Before Violence to a Phase II Violence and from there into a Phase III After Violence. Violence can be prevented, like diseases; but our ability to prevent violence is still at a primitive stage. Not that long time ago the general cure for disease was blood-letting, by incision or by leeches, to bleed patients. A strong stand against blood-letting is not necessarily rooted in moralism but more in pragmatism: it does not work, something else works better. The same could apply to the blood- letting in wars, as “battles” or “operations”. The moral stance is important. But the pragmatic challenge to find something that works better is even more so.

This is very far from a play with words. If conflict is confused with violence then basic, potentially fatal clashes of goals will not be detected until the first act of violence occurs, meaning that nothing will be done before there is “trouble”. Governments, including the UN Security Council, tend to fall into that trap. And, equally sad, when no more violence occurs “peace” is often declared, confusing that complex state with the cease-fire of neither peace, nor war. The medical parallel is the confusion of health with the absence of symptoms like fever.

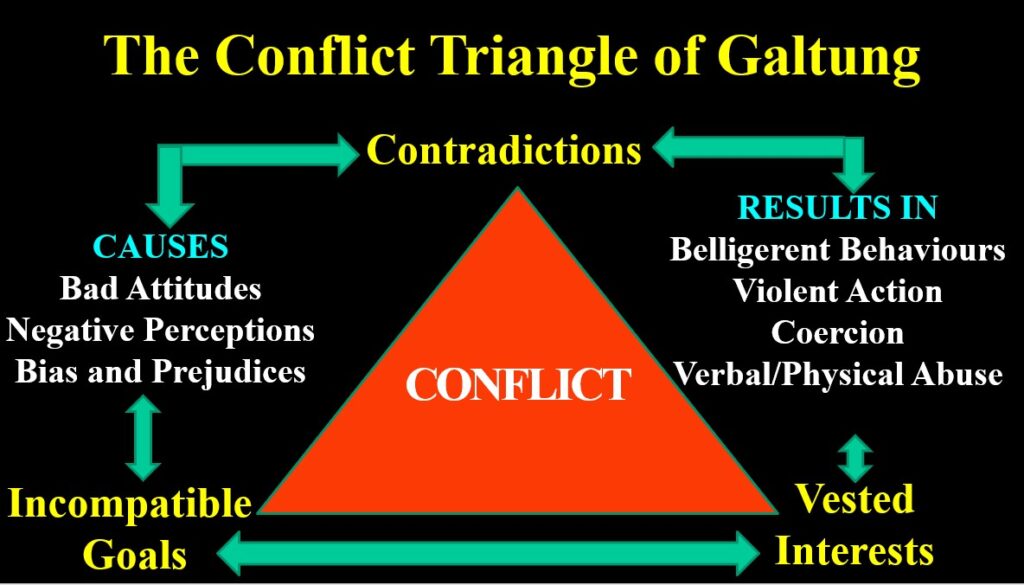

There is more to conflict than C for contradiction; there is also A for attitude and B for behavior, the ABC-triangle. Attitudes include emotions and cognitions, ranging from boiling hatred to frozen apathy where emotions are concerned; and from the simplest to the most complex where cognitions are concerned. Do they see many parties or only two; many goals or only one, like struggle for world dominion? To get me/us?

The behavior we generally focus on can range from extreme violence to apathy, like for attitudes. Apathy is often more dangerous than hatred and violence. An activist may be persuaded to channel his energy in another, more compassionate and less violent direction. A passivist has often an egocentric cost-benefit analysis, concerned with staying out of trouble. Media focus on activists, mindless even of majorities of passivists.

The root of the conflict is the contradiction. Negative attitudes and behavior are like metastases to the root cancer. They may become prime causes in their own right, but the root cause of conflict is the same: parties that have incompatible goals. The idea of eliminating the party that stands in the way, or at least to incapacitate him, comes easily. Too easily.

We can have conflicts with fully fledged ABC-triangles:

- at the micro level: intra- and inter-personal conflict

- at the meso level: inter-group, but intra-society conflict

- at the macro level: inter-state, inter-nation (not the same)

- at the mega level: inter-region, inter-civilization (mega-state and mega-nation).

The basic principles are the same.

The liberal mistake in approaching conflict is to focus on 1 only, religiously or psychologically; the conservative mistake to focus on 2 only, clamping down on all signs of violence; and the Marxist approach to focus on 3 only, like the contradiction between capital and labor, regardless of costs in 1 and 2 terms.

We have to approach all three if we want conflict solution: something acceptable and sustainable. A good place to start is the root conflict, trying to solve it or at least to transform it so that the parties can live with it reasonably creatively and non-violently.

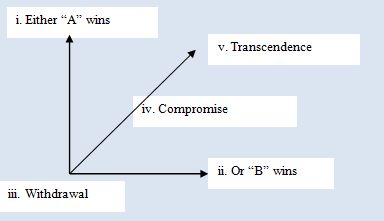

If we limit ourselves to simple conflicts with only two goals, held by the same party or by different parties A and B, then there are always five possible outcomes, central to the TRANSCEND approach:

- A gets all, B gets nothing (victory/defeat)

- B gets all, A gets nothing (defeat/victory)

- A gets some, B gets some (compromise)

- A gets all, B gets all (positive transcendence).

- A gets nothing, B gets nothing (withdrawal, but could also be negative transcendence, going beyond the contradiction)

An example: Ecuador and Peru have a conflict over a zone in the Andes. To obtain [1] or [2] a war is a classical instrument. To obtain [3], dividing by drawing a border, international law or war can be used (border=cease-fire line). [4] could be to do nothing (which they had done for a large part of 54 years), or to give the zone to the indigenous or an intergovernmental organizations, like the UN, the OEA. And [5] could be a “binational zone with natural park” (as proposed by this author, the outcome in 1998). The first two outcomes are extremist, privileging one party only, often associated with violence. The next three outcomes are symmetric, giving nothing, something or everything to both. They can often be combined in a “peace diagonal”. The other diagonal, Compromise, or else Fight it out! (the “war diagonal”) is frequently encountered. The listing above has five possible outcomes, and they can be combined. Many people (including politicians), how- ever, may have none of them on their mind. The whole conflict landscape is foggy, no points, no paths. Only A and B. And violence erupts.

But some people have clear ideas: “to win is not everything – it is the only thing”. Could be a spoilt actor (person, group, state, nation, region, civilization) very used to getting his (usually a he) will. Or to winning too many sports competitions.

“To win is the only thing” opens for a very poor conflict culture, indeed. A conflict culture privileges/preselects some conflict outcomes over others. Thus, military people are focusing, by definition, on [1] with [2] at the back of their minds; diplomats on [3] (compromise through negotiation, with [1] or [2] at the back of their minds); merchants on [3] (compromise through bargaining with [5] at the back of their minds), and so on, and so forth. Men tend more toward the war diagonal, women more toward the peace diagonal. In general.

Different groups, and indeed different persons, have more or less peace productive conflict cultures, in other words. The mapping of groups on the 25=32 conflict cultures is crucial to understand what happens in a conflict, including in a mediation process. The parties, including the mediator (who is also some kind of party) enter with their ideas of how conflicts have to be handled, a reason why it always makes sense to ask parties to reflect on conflict in general, not only the case disputed.

Who would privilege positive transcendence, an outcome that requires much creativity? Maybe rabbis, buddhist monks, artists, engineers, architects, and women rather than men (but women are often too shy and short on self-respect to be openly creative).

General formula: first, identify the goals of all parties. Second: distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate goals. Third: bridge, go beyond, transcend the incompatibility among legitimate goals. Like politics: the art of the impossible. Then peacebuilding, violence reduction, and reconciliation; in that order. The time for violence prevention is now. The key approaches include producing, early, through deep dialogues with all parties, alternative images of sustainable, potentially acceptable conflict transformation. This should always be accompanied by massive peacebuilding, depolarizing social and mental structures. And by violence reduction. If governments know only military approaches, only after violence has broken out, then nongovernments could play a major role with nonviolent approaches. Some organizations are now planning that, flooding conflict arenas with nonviolent conflict workers.

Unfortunately, governments have a tendency to do this in the opposite order, enforcing a ceasefire (“peace enforcement” as they call it, with decommissioning of arms), organizing “peacebuilding” at the top around a conference table, arriving at an “agreement” with no organic base. No party will hand over all their arms with no real agreement in sight. The process has to start with an image of a solution to inspire optimism, hope, and mobilize for peace.

Then, if there has been violence: reconciliation. This is a very complex process governments do not know how to do, with the exception of the textbooks of Germany (and then only West Germany) and the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. There is a healing aspect, not only individual, also to liberate revanchist and triumphalist nations from trauma and glory syndromes that may be very dangerous to either and both, as wars of revenge or follow-up. And there is a closure aspect, impossible without some conflict transformation. The formula, the winner dictates the peace is a recipe for a disaster of revenge/ revanche. Reconciliation is to violence what transformation is to conflict.

The texts at the end have much material on transformation and reconciliation. Here we shall only expand the conflict vision by adding two more types of violence to the direct violence (verbal and/or physical): structural violence, and cultural violence.

Like direct violence structural violence hurts and harms. But there is no actor intending this to happen; it just happens. Structural violence comes in three varieties:

- political structural violence: depriving people of freedom, like in frozen autocracies, or the frozen division of Koreans;

- economic structural violence: depriving people of the basic somatic needs at the bottom of the world economic system, dying at the tune of 100 000 per day of food and healing deficits;

- cultural structural violence: depriving people of their own culture, dying spiritually; at the tune of? We do not know. We shall return to this point in section 10 below.

Structural violence usually starts with major acts of direct violence, like building the wall (of shame) around West Berlin August 1961. But after some time actors and intentions are forgotten and what remains is a highly concrete structure. The cultural variety may start with invasion/colonization, in the name of some mission, leading to conversion/exclusion/killing. After some time it all becomes institutionalized, structural.

Cultural violence are those aspects of any culture that legitimize direct and/or structural violence. The cultures of war, in other words. The specialty of the Brahmin (intellectuals and clerics) as opposed to the direct violence, the specialty of the Kshatriya (politicians, military) and the structural economic violence of the Vaisya (merchants). And the victims? Today above all Sudra, common people; among them above all women and children.

TO READ FULL PAPER Download PDF file:

RETHINKING CONFLICT – THE CULTURAL APPROACH

____________________________________________________

Johan Galtung (24 Oct 1930 – 17 Feb 2024), a professor of peace studies, dr hc mult, was the founder of TRANSCEND International, TRANSCEND Media Service, and rector of TRANSCEND Peace University. He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize numerous times and was awarded among others the 1987 Right Livelihood Award, known as the Alternative NPP. Galtung has mediated in over 150 conflicts in more than 150 countries, and written more than 170 books on peace and related issues, 96 as the sole author. More than 40 have been translated to other languages, including 50 Years-100 Peace and Conflict Perspectives published by TRANSCEND University Press. His book, Transcend and Transform, was translated to 25 languages. He has published more than 1700 articles and book chapters and over 500 Editorials for TRANSCEND Media Service. More information about Prof. Galtung and all of his publications can be found at transcend.org/galtung

Johan Galtung (24 Oct 1930 – 17 Feb 2024), a professor of peace studies, dr hc mult, was the founder of TRANSCEND International, TRANSCEND Media Service, and rector of TRANSCEND Peace University. He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize numerous times and was awarded among others the 1987 Right Livelihood Award, known as the Alternative NPP. Galtung has mediated in over 150 conflicts in more than 150 countries, and written more than 170 books on peace and related issues, 96 as the sole author. More than 40 have been translated to other languages, including 50 Years-100 Peace and Conflict Perspectives published by TRANSCEND University Press. His book, Transcend and Transform, was translated to 25 languages. He has published more than 1700 articles and book chapters and over 500 Editorials for TRANSCEND Media Service. More information about Prof. Galtung and all of his publications can be found at transcend.org/galtung

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER STAYS POSTED FOR 2 WEEKS BEFORE BEING ARCHIVED

Tags: Conflict, Conflict Analysis, Conflict Transformation, Conflict studies, Cultural violence, Direct violence, Johan Galtung, Peace Research, Peace Studies, Structural violence

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 12 Aug 2024.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Rethinking Conflict: The Cultural Approach, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Join the discussion!

We welcome debate and dissent, but personal — ad hominem — attacks (on authors, other users or any individual), abuse and defamatory language will not be tolerated. Nor will we tolerate attempts to deliberately disrupt discussions. We aim to maintain an inviting space to focus on intelligent interactions and debates.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

FEATURED RESEARCH PAPER: