Tao Te Ching

ACADEMIA-KNOWLEDGE-SCHOLARSHIP, RELIGION, EDUCATION, LITERATURE, INSPIRATIONAL, SPIRITUALITY, 30 Jul 2018

Lao Tzu – TRANSCEND Media Service

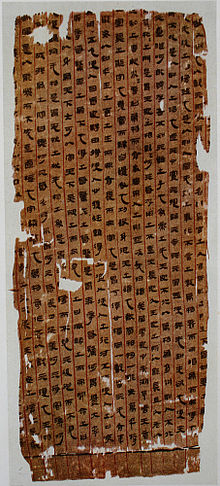

The Tao Te Ching is a Chinese classic text traditionally credited to the 6th-century BC sage Laozi. The text’s authorship, date of composition and date of compilation are debated. The oldest excavated portion dates back to the late 4th century BC, but modern scholarship dates other parts of the text as having been written—or at least compiled—later than the earliest portions of the Zhuangzi.

The Tao Te Ching, along with the Zhuangzi, is a fundamental text for both philosophical and religious Taoism. It also strongly influenced other schools of Chinese philosophy and religion, including Legalism, Confucianism, and Buddhism, which was largely interpreted through the use of Taoist words and concepts when it was originally introduced to China. Many Chinese artists, including poets, painters, calligraphers, and gardeners, have used the Tao Te Ching as a source of inspiration. Its influence has spread widely outside East Asia and it is among the most translated works in world literature.

Tao Te Ching is the Wade-Giles romanization of the same name as the pinyin Daodejing and should be pronounced in the same way That is, its ⟨t⟩s should be pronounced closer to English ⟨d⟩s. The Chinese characters in the title are:

Dào/tao literally means “way”, or one of its synonyms, but was extended to mean “the Way”. This term, which was variously used by other Chinese philosophers (including Confucius, Mencius, Mozi, and Hanfeizi), has special meaning within the context of Taoism, where it implies the essential, unnamable process of the universe.

Dé/te means “virtue”, “personal character”, “inner strength” (virtuosity), or “integrity”. The semantics of this Chinese word resemble English virtue, which developed from the Italian virtù, an archaic sense of “inner potency” or “divine power” (as in “healing virtue of a drug”) to the modern meaning of “moral excellence” or “goodness”. Compare the compound word taote (Chinese: 道德; pinyin: Dàodé; literally: “ethics”, “ethical principles”, “morals” or “morality”). Jīng/ching as it is used here means “canon”, “great book”, or “classic”.

The first character can be considered to modify the second or can be understood as standing alongside it in modifying the third. Thus, Tao Te Ching can be translated as The Classic of the Way’s Virtue(s), The Book of the Tao and Its Virtue, or The Book of the Way and of Virtue. It has also been translated as The Tao and its Characteristics, The Canon of Reason and Virtue, The Classic Book of Integrity and the Way, and A Treatise on the Principle and Its Action.

Ancient Chinese books were commonly referenced by the name of their real or supposed author, in this case the “Old Master”, Laozi or Lao-tze. As such, the Tao Te Ching is also sometimes referred to as The Lao-tze, especially in Chinese sources.

Other titles of the work include the honorific “Sutra” or “Truthful Classic of the Way and Its Power” (Daode Zhenjing) and the descriptive 5,000-character Classic (Wuqian Wen).

Internal structure

The Tao Te Ching is a short text of around 5,000 Chinese characters in 81 brief chapters or sections (章). There is some evidence that the chapter divisions were later additions—for commentary, or as aids to rote memorization—and that the original text was more fluidly organized. It has two parts, the Tao Ching (道經; chapters 1–37) and the Te Ching (德經; chapters 38–81), which may have been edited together into the received text, possibly reversed from an original Te Tao Ching. The written style is laconic, has few grammatical particles, and encourages varied, contradictory interpretations. The ideas are singular; the style poetic. The rhetorical style combines two major strategies: short, declarative statements and intentional contradictions. The first of these strategies creates memorable phrases, while the second forces to create reconciliations of the supposed contradictions.

Historical authenticity of the author

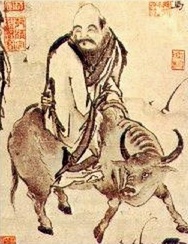

The Tao Te Ching is ascribed to Lao Tzu, whose historical existence has been a matter of scholastic debate. His name, which means “Old Master”, has only fueled controversy on this issue.

The first reliable reference to Laozi is his “biography” in Shiji (63, tr. Chan 1963:35–37), by Chinese historian Sima Qian (c. 145–86 BC), which combines three stories. First, Lao Tzu was a contemporary of Confucius (551–479 BC). His surname was Li (李 “plum”), and his personal name was Er (耳 “ear”) or Dan (聃 “long ear”). He was an official in the imperial archives, and wrote a book in two parts before departing to the West. Second, Laozi was Lao Laizi (老來子 “Old Come Master”), also a contemporary of Confucius, who wrote a book in 15 parts. Third, Laozi was the grand historian and astrologer Lao Dan (老聃 “Old Long-ears”), who lived during the reign (384–362 BC) of Duke Xian (獻公) of Qin).

Generations of scholars have debated the historicity of Laozi and the dating of the Tao Te Ching. Linguistic studies of the text’s vocabulary and rhyme scheme point to a date of composition after the Shi Jing yet before the Zhuangzi. Legends claim variously that Laozi was “born old”; that he lived for 996 years, with twelve previous incarnations starting around the time of the Three Sovereigns before the thirteenth as Laozi. Some Western scholars have expressed doubts over Lao Tzu’s historical existence, claiming that the Tao Te Ching is actually a collection of the work of various authors.

Principal versions

The Tao Te Ching has been translated into Western languages over 250 times, mostly to English, German, and French. According to Holmes Welch, “It is a famous puzzle which everyone would like to feel he had solved.” The first English translation of the Tao Te Ching was produced in 1868 by the Scottish Protestant missionary John Chalmers, entitled The Speculations on Metaphysics, Polity, and Morality of the “Old Philosopher” Lau-tsze. It was heavily indebted to Julien’s French translation and dedicated to James Legge, who later produced his own translation for Oxford’s Sacred Books of the East.

Other notable English translations of the Tao Te Ching are those produced by Chinese scholars and teachers: a 1948 translation by linguist Lin Yutang, a 1961 translation by author John Ching Hsiung Wu, a 1963 translation by sinologist Din Cheuk Lau, another 1963 translation by professor Wing-tsit Chan, and a 1972 translation by Taoist teacher Gia-Fu Feng together with his wife Jane English.

Many translations are written by people with a foundation in Chinese language and philosophy who are trying to render the original meaning of the text as faithfully as possible into English. Some of the more popular translations are written from a less scholarly perspective, giving an individual author’s interpretation. Critics of these versions claim that their translators deviate from the text and are incompatible with the history of Chinese thought. Russell Kirkland goes further to argue that these versions are based on Western Orientalist fantasies, and represent the colonial appropriation of Chinese culture. In contrast, Huston Smith, scholar of world religions, said of the Stephen Mitchell version, “This translation comes as close to being definitive for our time as any I can imagine. It embodies the virtues its translator credits to the Chinese original: a gemlike lucidity that is radiant with humor, grace, largeheartedness, and deep wisdom.” Other Taoism scholars, such as Michael LaFargue and Jonathan Herman, argue that while they don’t pretend to scholarship, they meet a real spiritual need in the West. These Westernized versions aim to make the wisdom of the Tao Te Ching more accessible to modern English-speaking readers by, typically, employing more familiar cultural and temporal references.

(Text from Wikipedia)

Download PDF file – English translator unknown:

Tao Te Ching – Lao Tzu

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 30 Jul 2018.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Tao Te Ching, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

ACADEMIA-KNOWLEDGE-SCHOLARSHIP:

- Academia at the Crossroads: Indoctrination, Systemic Violence, and the Security Risks of Rentier Capitalism

- The Futility of Genocide Studies after Gaza

- Are We as Area Studies Scholars Guilty of Negligence in Allowing Genocides to Happen in the Regions We Study?

RELIGION:

- The Profound Influence of and Dialogue with Islam on Mahatma Gandhi’s Peace and Ethical Philosophies

- The Relations between the Armenian Apostolic Church and Other Christian Churches

- Greeting for Pesach

EDUCATION:

- Misconception and Right Concept of Peace Education: Theory and Praxis

- Financing Higher Education to Build Non-exploitative Society for Peace

- Relevance of Peace Education

LITERATURE:

- Naomi Klein and VV Ganeshananthan Win Women’s Prize Literary Awards

- The Dalit and the Brahmin

- Gandhi: The Soul Force Warrior

INSPIRATIONAL:

- Declaration of the Independence of the Mind

- Never Again

- A Winter Walk with Thoreau: The Transcendentalist Way of Finding Inner Warmth in the Cold Season

SPIRITUALITY: