The Lot of the Exploited, Discriminated and Oppressed (Part 2)

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 20 Dec 2021

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

Is It Predestination, Karma, or Hedonistic Colonial Subjugation by People of Aryan Origins? An Odyssey of Generational Suffering of Humanoids of Colour

17 Dec 2021 – In Part 1 of this paper[1] the oppression and subjugation of the Scheduled Castes, formerly called the Dalits, the “Untouchables” people in India, on the basis of the tenets of Hinduism, whereby the lot of the lowest caste people was predestined on their karmas in their previous cycle of life; The process of Reincarnation. This oppression was justifiable using religion as an official reason for the discrimination, abuse, rape and even first-degree murder of the Dalits. There is no recourse for justice in the judicial system as the police force is often bribed by high caste individuals in the community.

This paper analyses the plight of the dark-skinned humanoids, based on colonial expansion, invasion and expropriation of the land of the Hereros[2] in the western part of Southern Africa, presently called Namibia, by the colonial forces of Imperial Germany in late 19th century.

Namibia was previously called South West Africa and lies on the eastern Atlantic seaboard, neighbouring South Africa[3], Angola[4] and Botswana[5]. In addition, smaller areas of Zambia[6] and Zimbabwe[7] borders Namibia, as well. The division between Namibia and Botswana is an arbitrary one, separating the indigenous people of a relatively common genealogy. Namibia’s extent can be divided into three topographic zones from west to east.[8] The coastal Namib Desert runs along the country’s coast on the Atlantic Ocean. It gives way to the Central Plateau to the west with the Kalahari Desert located further inwards.

The Namib Desert is both rocky and sandy. It has an average width of around 50 to 80 miles. The elevation of the Central Plateau varies from 975 to 1,980 m. Most of the country’s farmlands are confined to this region. Large parts of the plateau are covered by savanna, scrub, and woodlands. To the north, the plateau gives way to several river valleys like Kunene and Okavango. The Orange River Valley lies to the south of this plateau. The 2,573 m tall Mount Brand, Namibia’s highest mountain, is located on the western edge of the plateau. The Swakop, Kuiseb, and Fish are some of the major rivers of the country. The Skeleton Coast of Namibia, is infamous for its dense fogs that results in numerous shipwrecks in the region. Namibia is divided into 14 regions for administrative efficiency.

With an area of 161,514sq. km, the Karas Region is the largest by area in the country while the Khomas Region is the most populous one. Windhoek, Namibia’s capital and largest city is located in the Khomas Region. With a long coastline on the Atlantic Ocean, Namibia has several islands, including the Shark Island, as well and the Caprivi Strip, a geographic salient protruding from the country’s northeastern corner. The total Area is 824,292.00 km2, the Land Area is 823,290.00 km2, Water Area is 1,002.00 km2 with a population of 2,494,530. The largest city is Windhoek with a population of 431,171.[9]

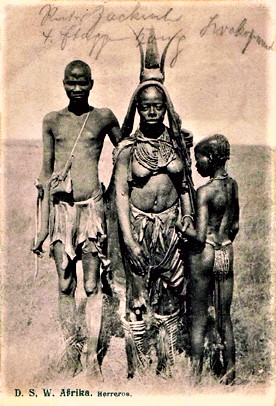

The Herero, also known as Ovaherero, are a Bantu ethnic group inhabiting parts of Southern Africa. The majority reside in Namibia, with the remainder found in Botswana and Angola. There were an estimated 250,000 Herero people in Namibia in 2013. They speak Otjiherero, a Bantu language. Hereros are also resident in Angola, numbering 25,000, Botswana: 19,000 and in Namibia, presently numbering 273,000. The big ball gown dress and the head gear are the main wear for women while men are mostly seen with leather hats and walking sticks.[10] Unlike most Bantu, who are primarily subsistence farmers,[11] the Herero are traditionally pastoralists. They make a living tending livestock.[12] Cattle terminology in use among many Bantu pastoralist groups testifies that Bantu herders originally acquired cattle from Cushitic pastoralists inhabiting Eastern Africa. After the Bantu settled in Eastern Africa, some Bantu nations spread south. Linguistic evidence also suggests that the Bantu borrowed the custom of milking cattle from Cushitic peoples[13]; either through direct contact with them or indirectly via Khoisan intermediaries who had acquired both domesticated animals and pastoral techniques from Cushitic migrants.[14]

Pre-colonially, in the 15th century, the Herero migrated to the present day Namibia from the east and established themselves as herdsmen. In the beginning of the 19th century, the Nama from South Africa, who already possessed some firearms, entered the land and were followed, in turn, by white merchants and German missionaries. At first, the Nama began displacing the Herero, leading to bitter warfare between the two groups, which lasted the greater part of the 19th century. Later the two peoples entered into a period of cultural exchange[15] During the late 18th century, the first Europeans began entering to permanently settle the land. Primarily in Damaraland, German settlers acquired land from the Herero in order to establish farms. In 1883, the merchant Franz Adolf Eduard Lüderitz entered into a contract with the native elders. The exchange later became the basis of German colonial rule. The territory became a German colony under the name of German South West Africa.

Chief of the neighbouring Herero, Maharero rose to power by uniting all the Herero.[16] Faced with repeated attacks by the Khowesin, a clan of the Khoekhoe under Hendrik Witbooi, he signed a protection treaty on 21 October 1885 with Imperial Germany’s colonial governor Heinrich Ernst Göring (father of convicted war criminal Hermann Göring) but did not cede the land of the Herero. This treaty was renounced in 1888 due to lack of German support against Witbooi but it was reinstated in 1890.[17] The Herero leaders repeatedly complained about violation of this treaty, as Herero women and girls were raped by German soldiers, a crime that the German authorities were reluctant to punish.[18]In 1890 Maharero’s son, Samuel, signed a great deal of land over to the Germans in return for helping him to ascend to the Ovaherero throne, and to subsequently be established as paramount chief.[19] German involvement in ethnic fighting ended in tenuous peace in 1894.[20] In that year, Theodor Leutwein became governor of the territory, which underwent a period of rapid development, while the German government sent the Schutztruppe (imperial colonial troops) to pacify the region.[21]

Soon after, conflicts between the German colonists and the Herero herdsmen began. Controversies frequently arose because of disputes about access to land and water, but also the legal discrimination against the native population by the white immigrants.[22]

In the late 19th and early 20th century, imperialism and colonialism in Africa peaked, affecting especially the Hereros and the Namas. European powers were seeking trade routes and railways, as well as more colonies. Germany officially claimed their stake in a South African colony in 1884, calling it German South West Africa until it was taken over in 1915. The first German colonists arrived in 1892[23], and conflict with the indigenous Herero and Nama people began. As in many cases of colonisation, the indigenous people were not treated fairly.[24] Between 1893 and 1903, the Herero and Nama people’s land and cattle were progressively being taken by German colonists.

The Herero and Namaqua genocide was a campaign of ethnic extermination and collective punishment waged by the German Empire against the Herero , the Nama, and the San in German South West Africa. It was the first genocide of the 20th century[25], occurring between 1904 and 1908. In January 1904, the Herero people, who were led by Samuel Maharero[26], and the Nama people, who were led by Captain Hendrik Witbooi[27], rebelled against German colonial rule. On January 12, they attacked more than 100 settlers in the area of Okahandja, and quite notably, they spared women and children, as well as all British people who were their allies at the time.[28]

In August, German General Lothar von Trotha defeated the Ovaherero in the Battle of Waterberg and drove them into the desert of Omaheke, where most of them died of dehydration. In October, the Nama people also rebelled against the Germans, only to suffer a similar fate. The Herero and Nama resisted expropriation[29] over the years, but they were unorganised and the Germans defeated them with ease. In 1903, the Herero people learned that they were to be placed in reservations,[30] leaving more room for colonists to own land and prosper. In 1904, the Herero and Nama began a great rebellion that lasted until 1907, ending with the near destruction of the Herero people. “The war against the Herero and Nama was the first in which German imperialism resorted to methods of genocide”[31] Roughly 80,000 Herero lived in German South West Africa at the beginning of Germany’s colonial rule over the area, while after their revolt was defeated, they numbered approximately 15,000. In a period of four years, approximately 65,000 Herero people were killed, with a serious intent by imperial Germany to engage in a foreign policy of annihilation and total extinction of the Herero people.[32]

Samuel Maharero, the Supreme Chief of the Herero, led his people in a large-scale uprising on January 12, 1904, against the Germans.[33] The Herero, surprising the Germans with their uprising, had initial success. However, German General Lothar von Trotha took over as leader in May 1904.[34] In August 1904, he devised a plan to annihilate the Herero nation.[35] The plan was to surround the area where the Herero were, leaving but one route for them to escape, into the desert. The Herero battled the Germans. It was when the majority had escaped through the only passage made available by the Germans, and had been systematically prevented from approaching watering holes, that starvation began to take its toll. It was then that the Herero uprising changed from war, to genocide.[36] Lothar von Trotha called the conflict a “race war.” He declared in the German press that “no war may be conducted humanely against non-humans” and issued an “annihilation order”: “… The Herero are no longer German subjects. They have murdered and stolen, they have cut off the ears, noses, and other body parts of wounded soldiers, now out of cowardice they no longer want to fight. I tell the people: Anyone who delivers one captain will receive 1,000 marks, whoever delivers Samuel Maharero will receive 5,000 marks. The Herero people must, however, leave the land. If the populace does not do this, I will force them with the Groot Rohr (cannon). Within the German borders every Herero, with or without a gun, with or without cattle, will be shot. I will no longer accept women and children, I will drive them back to their people or I will have them shot at.”[37] This was the root of the Nazi Holocaust in World War 11in which over six million people of Jewish origins were exterminated in addition to Romas[38], Gypsies[39] and Russian prisoners[40] of war by the Third Reich of Hitler.

On the 100th anniversary of the Herero massacre, the German Minister for Economic Development and Cooperation Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul commemorated the dead onsite and apologised for the crimes on behalf of all Germans. Hereros and Namas demanded financial reparations, however in 2004 there was only minor media attention in Germany on this matter.[41] Only in May 2021, the German government agreed to pay €1.1 billion over 30 years to fund projects in communities that were impacted by the genocide.[42]

The Herero and Nama Genocide by Imperial Germany was that it was based on the Aryan superiority of the colonial Germans. It was the precursor of Nazi Holocaust, as a prequel in Africa, in which indigenous people of Africa, who were considered sub-humans, were systematically exterminated by the colonial forces. Racial tension was also at play. The White, German settlers often referred to Black Africans as “baboons”[43] and treated them with contempt.[44]

One missionary, at the time, reported: “The real cause of the bitterness among the Hereros toward the Germans is without question the fact that the average German looks down upon the natives as being about on the same level as the higher primates (‘baboon’ being their favourite term for the natives) and treat them like animals. The settler holds that the native has a right to exist only in so far as he is useful to the white man. This sense of contempt led the settlers to commit violence against the Hereros.”[45] The contempt manifested itself particularly in the mistreatment of native women. In a practice referred to by the Germans as “Verkafferung”, the native women were taken by the German man by peace and by force.[46]

Furthermore, unethical, carte blanche, medical experiments were conducted on the Herero prisoners, with reference to their illnesses or their recoveries from them, as scientific research.[47] Experiments on live prisoners were also performed by Dr. Bofinger, who injected Herero who were suffering from scurvy with various substances including arsenic and opium; afterwards he researched the effects of these substances via autopsy.[48]

Experimentation with the dead body parts of the prisoners was rife in German South West Africa Zoologist Leonhard Schultze [de] (1872–1955) noted taking “body parts from fresh native corpses” which according to him was a “welcome addition”, and he also noted that he could use prisoners for that purpose.[49] An estimated 300 skulls[50] were sent to Germany for experimentation, in part from concentration camp prisoners.[51] In October 2011, after three years of talks, the first 20 of an estimated 300 skulls stored in the museum of the Charité were returned to Namibia for burial.[52] In 2014, 14 additional skulls were repatriated by the University of Freiburg.[53]

The Herero-Nama genocide has focused the attention of historians who study complex issues of commonalties between the Herero genocide and The Holocaust.[54] It is argued that the Herero genocide set a precedent in Imperial Germany that would later be followed by Nazi Germany’s establishment of death camps.[55] It is also important to note that some of the principal role players were participating in both the genocides, initially innovated in Africa and perfected in Europe, during World War11.

According to Benjamin Madley, the German experience in South West Africa was a crucial precursor to Nazi colonialism and genocide. He argues that personal connections, literature, and public debates served as conduits for communicating colonialist and genocidal ideas and methods from the colony to Germany.[56] Tony Barta, an honorary research associate at La Trobe University, argues that the Herero genocide was an inspiration for Hitler in his war against the Jews, Slavs, Romani, and others who he described as “non-Aryans”.[57]

According to Clarence Lusane, Eugen Fischer’s medical experiments can be seen as a testing ground for medical procedures which were later followed during the Nazi Holocaust.[58] Fischer later became chancellor of the University of Berlin, where he taught medicine to Nazi physicians. Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer was a student of Fischer, Verschuer himself had a prominent pupil, Josef Mengele, the “Angel of Death”[59] Franz Ritter von Epp, who was later responsible for the liquidation of virtually all Bavarian Jews and Roma as governor of Bavaria, took part in the Herero and Nama genocide as well.[60]

Mahmood Mamdani argues that the links between the Herero genocide and the Holocaust are beyond the execution of an annihilation policy and the establishment of concentration camps and there are also ideological similarities in the conduct of both genocides. Focusing on a written statement by General Trotha which is translated as:-

I destroy the African tribes with streams of blood … Only following this cleansing can something new emerge, which will remain.[61]

Mamdani takes note of the similarity between the aims of the General Trotha and the Nazis. According to Mamdani, in both cases there was a Social Darwinist notion of “cleansing”, after which “something new” would “emerge”.[62]

The Bottom Line is that the racial philosophy of annihilation of sub-humanoids is entirely based on Aryan superiority and it is still prevalent in the 21st century. The reality is that the threat of social Darwinist notion of ethnic cleansing is existential and ready to be repeated, once again. Regrettably, the world bodies and the multiple, so called human rights organisations are powerless, doing nothing at all, as they are there for self-glory, financial gain and are all “brain dead”[63] in the wise words of Emmanuel Macron[64], for which he was justifiably unrepentant.[65]

References:

[1] https://www.transcend.org/tms/2021/12/the-lot-of-the-exploited-discriminated-and-oppressed-part-1/

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people

[3] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Africa

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angola

[5] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Botswana

[6] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zambia

[7] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zimbabwe

[8] https://www.worldatlas.com/maps/namibia

[9] https://www.worldatlas.com/r/w960-q80/img/flag/na-flag.jpg

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people#:~:text=The%20big%20ball%20gown%20dress%20and%20the%20head%20gear%20are%20the%20main%20wear%20for%20women%20while%20men%20are%20mostly%20seen%20with%20leather%20hats%20and%20walking%20sticks.

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people#:~:text=Immaculate%20N.%20Kizza,start%20permanent%20settlements.%22

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people#:~:text=Mark%20Cocker%2C%20Rivers%20of%20Blood%2C%20Rivers%20of%20Gold%3A%20Europe%27s%20Conquest%20of%20Indigenous%20Peoples%2C%20Grove%20Press%2C%202001%2C%20p.%20276

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people#:~:text=Blench%2C%20Roger%20(8,the%20same%20region.

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people#:~:text=J.%20D.%20Fage,in%20East%20Africa.%22

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people#:~:text=The%20Herero%2C%20also%20known%20as%20Ovaherero%2C%20are%20a,2013.%20They%20speak%20Otjiherero%2C%20a%20Bantu%20language%20.

[16] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=Gewald%2C%20Jan%2DBart%20(1999).%20Herero%20Heroes%3A%20A%20Socio%2Dpolitical%20History%20of%20the%20Herero%20of%20Namibia%2C%201890%E2%80%931923.%20Oxford%3A%20James%20Currey.%20p.%C2%A061.%20ISBN%C2%A09780864863874.

[17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=Dierks%2C%20Klaus%20(2004).%20%22Biographies%20of%20Namibian%20Personalities%2C%20M.%20Entry%20for%20Maharero%22.%20klausdierks.com.%20Retrieved%2010%20June%202011.

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=Marcia%20Klotz%20(1994,as%20mere%20peccadilloes.%22

[19] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=Gewald%2C%20Jan%2DBart%20(1999).%20Herero%20Heroes%3A%20A%20Socio%2Dpolitical%20History%20of%20the%20Herero%20of%20Namibia%2C%201890%E2%80%931923.%20p.%C2%A029.%20ISBN%C2%A09780864863874

[20] Bridgman, Jon M. (1981) The Revolt of the Hereros, California University Press ISBN 978-0-520-04113-4

[21] https://web.archive.org/web/20140714191129/http://www.coedu.usf.edu/culture/Story/Story_Namibia.htm

[22] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people#:~:text=The%20Herero%2C%20also%20known%20as%20Ovaherero%2C%20are%20a,2013.%20They%20speak%20Otjiherero%2C%20a%20Bantu%20language%20.

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people#:~:text=Peace%20and%20freedom%2C%20Volume%2040%2C%20Women%27s%20International%20League%20for%20Peace%20and%20Freedom%2C%20page%2057%2C%20The%20Section%2C%201980

[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people#:~:text=The%20Herero%2C%20also%20known%20as%20Ovaherero%2C%20are%20a,2013.%20They%20speak%20Otjiherero%2C%20a%20Bantu%20language%20.

[25] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=David%20Olusoga%20(2015%2D04%2D18).%20%22Dear%20Pope%20Francis%2C%20Namibia%20was%20the%2020th%20century%27s%20first%20genocide%22.%20The%20Guardian.%20Retrieved%2026%20November%202015.

[26] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Maharero

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hendrik_Witbooi_(Namaqua_chief)

[28] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=they%20attacked%20more%20than%20100%20settlers%20in%20the%20area%20of%20Okahandja%2C%20and%20quite%20notably%2C%20they%20spared%20women%20and%20children%2C%20as%20well%20as%20all%20British%20people%20who%20were%20their%20allies%20at%20the%20time

[29] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people#:~:text=%22A%20bloody%20history%3A%20Namibia%E2%80%99s%20colonisation%22%2C%20BBC%20News%2C%2029%20August%202001

[30] Samuel Totten, Paul Robert Bartrop, Steven L. Jacobs (2007) Dictionary of Genocide: A-L, p.184, Greenwood Press, Westport, Conn. ISBN 978-0-31334-642-2

[31] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people#:~:text=Chalk%2C%20Frank%2C%20and%20Jonassohn%2C%20Kurt.%20The%20History%20and%20Sociology%20of%20Genocide%3A%20Analyses%20and%20Case%20Studies.%20Published%20in%20cooperation%20with%20the%20Montreal%20Institute%20for%20Genocide%20Studies.%20(Yale%20University%20Press%3A%20New%20Haven%20%26%20London%2C%201990)

[32] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people#:~:text=UN%20Whitaker%20Report%20on%20Genocide%2C%201985%2C%20paragraphs%2014%20to%2024%2C%20pages%205%20to%2010%20Prevent%20Genocide%20International

[33] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people#:~:text=The%20New%20York%20Times.%2018%20August%201904

[34] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people#:~:text=The%20Times%20(London,%5E

[35] Mahmood Mamdani (2001) When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, Princeton University Press, Princeton ISBN 978-0-69105-821-4

[36] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/25/germany-moves-to-atone-for-forgotten-genocide-in-namibia

[37] https://doi.org/10.1096%2Ffj.08-0202ufm

[38] https://www.theholocaustexplained.org/life-in-nazi-occupied-europe/oppression/roma/

[39] https://www.thoughtco.com/gypsies-and-the-holocaust-1779660

[40] https://ghb67.wordpress.com/2012/12/11/prisoner-of-war-holocaust/#:~:text=Some%20of%20the%20650%2C000%20Russian%20prisoners%20captured%20at,found%20alive%20in%20the%20camps%20after%20the%20war.

[41] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_people#:~:text=Krabbe%2C%20Alexander.%20%22Remembering%20Germany%27s%20African%20Genocide%22.%20OhmyNews%20International.%20Archived%20from%20the%20original%20on%202004%2D09%2D05.%20Retrieved%202004%2D08%2D06.

[42] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=Oltermann%2C%20Philip%20(2021%2D05%2D28).%20%22Germany%20agrees%20to%20pay%20Namibia%20%E2%82%AC1.1bn%20over%20historical%20Herero%2DNama%20genocide%22.%20The%20Guardian.%20Retrieved%202021%2D05%2D28.

[43] Drechsler, Horst (1980) Let Us Die Fighting: the struggle of the Herero and Nama against German imperialism (1884–1915), Zed Press, London ISBN 978-0-905762-47-0

[44] Bridgman, Jon M. (1981) The Revolt of the Hereros, California University Press ISBN 978-0-520-04113-4

[45] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=Samuel%20Totten%3B%20William%20S.%20Parsons%20(2009).%20Century%20of%20Genocide%2C%20Critical%20Essays%20and%20Eyewitness%20Accounts.%20New%20York%3A%20RoutledgeFalmer.%20p.%C2%A018.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D0%2D415%2D99085%2D1.

[46] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=Samuel%20Totten%3B%20William%20S.%20Parsons%20(2009).%20Century%20of%20Genocide%2C%20Critical%20Essays%20and%20Eyewitness%20Accounts.%20New%20York%3A%20RoutledgeFalmer.%20p.%C2%A019.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D0%2D415%2D99085%2D1.

[47] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=Benjamin%20Madley%20(2005,an%20extermination%20centre.%22

[48] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=Olusoga%2C%20David%3B%20Erichsen%2C%20Casper%20W.%20(2010).%20The%20Kaiser%27s%20Holocaust%3A%20Germany%27s%20Forgotten%20Genocide%20and%20the%20Colonial%20Roots%20of%20Nazism.%20London%2C%20ENG%3A%20Faber%20and%20Faber.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D0%2D571%2D23141%2D6.

[49] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=Zimmerman%2C%20Andrew%2C%20Anthropology,1908%2C%20S.%20VIII.

[50] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-15127992

[51] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=%22Der%20verleugnete%20V%C3%B6lkermord%22.%20Die%20Tageszeitung.%2029%20September%202011.

[52] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=%22Germans%20return%20skulls%20to%20Namibia%22.%20The%20Times.%2027%20September%202011.

[53] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=%22Repatriation%20of%20Skulls%20from%20Namibia%20University%20of%20Freiburg%20hands%20over%20human%20remains%20in%20ceremony%22.%20University%20of%20Freiburg.%204%20March%202014.%20Archived%20from%20the%20original%20on%202015%2D04%2D23.%20Retrieved%202015%2D04%2D21.

[54] David Johnson; Prem Poddar (2008) A Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures – Continental Europe and its Empires, p. 240, Edinburgh University Press ISBN 978-0-7486-3602-0

[55] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=%22Imperialism%20and%20Genocide%20in%20Namibia%22.%20Socialist%20Action.%20April%201999.%20Archived%20from%20the%20original%20on%202007%2D06%2D08.%20Retrieved%202007%2D06%2D12.

[56] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=Benjamin%20Madley%20(2005).%20%22From%20Africa%20to%20Auschwitz%3A%20How%20German%20South%20West%20Africa%20Incubated%20Ideas%20and%20Methods%20Adopted%20and%20Developed%20by%20the%20Nazis%20in%20Eastern%20Europe%22.%20European%20History%20Quarterly.%2035%20(3)%3A%20429%E2%80%9364.%20doi%3A10.1177/0265691405054218.%20S2CID%C2%A0144290873.

[57] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=David%20B.%20MacDonald%20(2007).%20Identity%20Politics%20in%20the%20Age%20of%20Genocide%3A%20The%20Holocaust%20and%20Historical%20Representation.%20Routledge.%20p.%C2%A097.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D1%2D134%2D08571%2D2.

[58] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=David%20B.%20MacDonald%20(2007).%20Identity%20Politics%20in%20the%20Age%20of%20Genocide%3A%20The%20Holocaust%20and%20Historical%20Representation.%20Routledge.%20p.%C2%A097.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D1%2D134%2D08571%2D2.

[59] http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/bulletin_of_the_history_of_medicine/summary/v085/85.3.kater.html

[60] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources/978-0-300-10098-3

[61] https://web.archive.org/web/20150112040848/http://www.windhuk.diplo.de/Vertretung/windhuk/en/03/Commemorative__Years__2004__2005/Seite__Speech__2004-08-14__BMZ.html

[62] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide#:~:text=Mamdani%2C%20Mahmood%20(2001).%20When%20Victims%20Become%20Killers%3A%20Colonialism%2C%20Nativism%2C%20and%20the%20Genocide%20in%20Rwanda.%20Princeton%2C%20NJ%3A%20Princeton%20University%20Press.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D0%2D691%2D05821%2D

[63] https://www.economist.com/europe/2019/11/07/emmanuel-macron-warns-europe-nato-is-becoming-brain-dead

[64] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emmanuel_Macron

[65] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-nato-braindead-idUSKBN1Y21JE

______________________________________________

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: Africa, Caste System, Colonialism, Dalits, Deep Culture, Deep Structure, Division, Europe, Genocide, Germany, India, Inequality, Karma, Namibia, Racism, Social conflict, Social contract, Social structures, Untouchables

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 20 Dec 2021.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: The Lot of the Exploited, Discriminated and Oppressed (Part 2), is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.