Peace Disruptors–The Conversion and Repurposing of Places of Worship (Part 4): Synagogues Defiled by Spanish Monarchy

TRANSCEND MEMBERS, 5 Dec 2022

Prof Hoosen Vawda – TRANSCEND Media Service

“The Odyssey of the Second Exodus Based on Religious Conflicts and Oppression”[1]

The exterior of what was once the El Transito Synagogue in Toledo, Spain, Founded in the 1300s: defiled and repurposed repeatedly.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons[2]

3 Dec 2022 – This series of publications present the conversions and defiling of existing places of worship into buildings of prayers of other religions, over the centuries, causing historical peace disruptions and deep-seated, endogenous acrimony, based on religious affiliation of a particular community. Part 4, in the series, discusses the suffering, trials and tribulation of the well-established and economically prosperous, Jewish community in Spain, in the city of Toledo and its surrounds, under the brutal Catholic monarchy of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. This religious genocide resulted in the deaths of thousands of civilian Jews, as part of a selected and targeted annihilation of the community, which was the aim of the Holocaust[3] during World War 11 under Adolph Hitler’s Nazi Party[4], stirring up of nationalistic fervour to justify the eradication of over six million Jews, Roamers, Gypsies and Russian prisoners of war, during this dark chapter of the recent history of humanoids, in Europe.

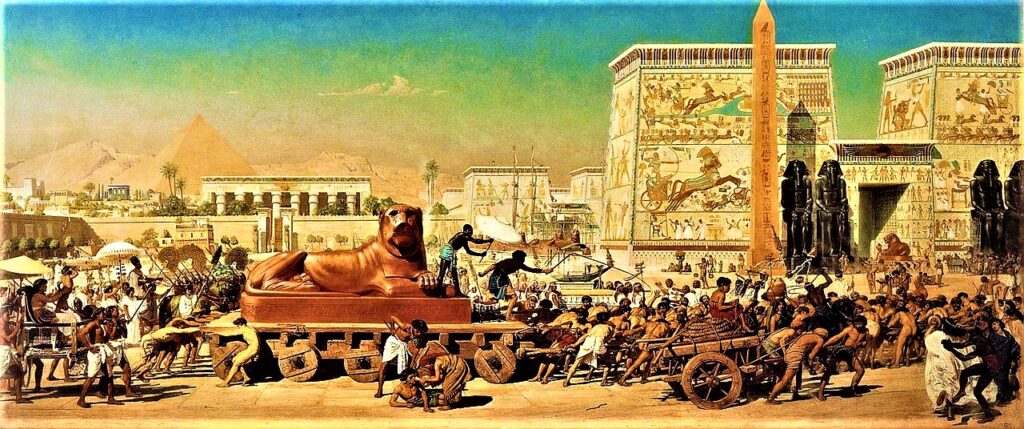

The first Exodus, according to the book of Exodus in the Bible[5], God’s covenant establishes relationship with the full-fledged nation of Israel. It is a narration of Israelite enslavement and eventual departure from Egypt, revelations at biblical Mount Sinai, and wanderings in the wilderness up to the borders of Canaan.[6] Its message is that the Israelites were delivered from slavery by Yahweh their god, and therefore belong to him by covenant.[7] The descendants of Abraham prosper after settling in Egypt, only to be enslaved by a tyrannical, fearful, hateful Egyptian Pharaoh, most probably Ramesses II, one of several suggested pharaohs in the Exodus narrative. God appoints Prophet Moses, assisted by his brother Aaron, as Moses has a speech impediment and requested God to allow Aaron to accompany him in his divinely ordained mission to the Pharaoh, to lead the people out of this eternal bondage.

The Eternal Bondage of the Children of Israel in Egypt by Pharaoh, probably Ramses 11[8], an 1867 painting by Edward Poynter

A Seder table setting, in Judaism, commemorating the Biblical Passover and Exodus[11] but is also symbolises the remembrance of the Second Exodus from Spain, 530 years ago

If conversos – converted Jews – stayed and continued to keep their faith in secret, but were found out by members of the Inquisition or exposed by neighbors, they would be tortured brutally into admitting their “sin” and later be burned, all of which was ordered by the Catholic Church, through the edict of the Pope at the time.

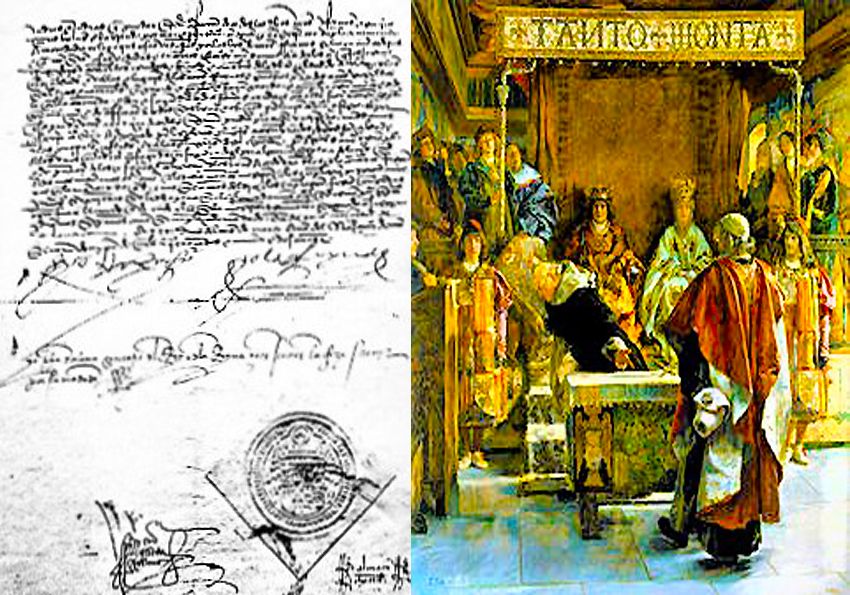

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition, Spanish: Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición, commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition Spanish: Inquisición española, was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile. It began toward the end of the Reconquista and was intended to maintain Catholic orthodoxy in their kingdoms and to replace the Medieval Inquisition, which was under Papal control. It became the most substantive of the three different manifestations of the wider Catholic Inquisition along with the Roman Inquisition and Portuguese Inquisition. The “Spanish Inquisition” may be defined broadly as operating in Spain and in all Spanish colonies and territories, which included the Canary Islands, the Kingdom of Naples and all Spanish possessions in North, Central, and South America. According to modern estimates, around 150,000 people were prosecuted for various offences during the three-century duration of the Spanish Inquisition, of whom between 3,000 and 5,000 were executed, approximately.7% of all cases.[14] The Inquisition was originally intended primarily to identify heretics among those who converted from Judaism and Islam to Catholicism. The regulation of the faith of newly converted Catholics was intensified after the royal decrees issued in 1492 and 1502 ordering Jews and Muslims to convert to Catholicism or leave Castile, resulting in hundreds of thousands of forced conversions, the persecution of conversos and moriscos, and the mass expulsions of Jews and of Muslims from Spain.[15] The Inquisition was abolished in 1834, during the reign of Isabella II, after a period of declining influence in the preceding century.

The Inquisition was initiated in 1478 by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain in a bid to maintain Catholic orthodoxy in their kingdoms and was under the direct control of the Spanish monarchy. In March 1492, Ferdinand and Isabella instituted the Alhambra Decree[16], otherwise known as the Edict of Expulsion, which ordered the expulsion of practicing Jews from the country, ranging between 45,000 to 200,000. However, almost 100 years before, in 1391, over half of Spain’s Jews had converted to Christianity as a result of religious persecution and pogroms. The 1492 Edict of Expulsion was instituted mainly to eliminate the influence of practicing Jews on Spain’s large converso population and ensure they did not revert to Judaism.

The expulsion of the Jews brought an end to the largest and most distinguished Jewish community in Europe.

As a background for the Alhambra Decree By the end of the eighth century, Muslim forces had conquered and settled most of the Iberian Peninsula.[17] Under Islamic law, the Jews, who had lived in the region since at least Roman times, were considered “People of the Book,” which was a protected status.[18] Compared to the repressive policies of the Visigothic Kingdom, who, starting in the sixth century had enacted a series of anti-Jewish statutes which culminated in their forced conversion and enslavement, the tolerance of the Muslim Moorish rulers of al-Andalus allowed Jewish communities to thrive. Jewish merchants were able to trade freely across the Islamic world, which allowed them to flourish, and made Jewish enclaves in Muslim Iberian cities great centers of learning and commerce. This led to a flowering of Jewish culture, as Jewish scholars were able to gain favor in Muslim courts as skilled physicians, diplomats, translators, and poets. Although Jews never enjoyed equal status to Muslims, in some Taifas, such as Granada, Jewish men were appointed to very high offices, including Grand Vizier.[19]

The Reconquista, or the gradual reconquest of Muslim Iberia by the Christian kingdoms in the North, was driven by a powerful religious motivation: to reclaim Iberia for Christendom following the Umayyad conquest of Hispania centuries before. By the fourteenth century, most of the Iberian Peninsula (present-day Spain and Portugal) had been reconquered by the Christian kingdoms of Castile, Aragon, León, Galicia, Navarre, and Portugal.

During the Christian re-conquest, the Muslim kingdoms in Spain became less welcoming to the dhimmi. In the late twelfth century, the Muslims in al-Andalus invited the fanatical Almohad dynasty from North Africa to push the Christians back to the North.[3] After they gained control of the Iberian Peninsula, the Almohads offered the Sephardim a choice between expulsion, conversion, and death. Many Jewish people fled to other parts of the Muslim world, and also to the Christian kingdoms, which initially welcomed them. In Christian Spain, Jews functioned as courtiers, government officials, merchants, and moneylenders.[3] Therefore, the Jewish community was both useful to the ruling classes and to an extent protected by them.[20]

As the Reconquista drew to a close, overt hostility against Jews in Christian Spain became more pronounced, finding expression in brutal episodes of violence and oppression. In the early fourteenth century, the Christian kings vied to prove their piety by allowing the clergy to subject the Jewish population to forced sermons and disputations.[3] More deadly attacks came later in the century from mobs of angry Catholics, led by popular preachers, who would storm into the Jewish quarter, destroy synagogues, and break into houses, forcing the inhabitants to choose between conversion and death.[3] Thousands of Jews sought to escape these attacks by converting to Christianity. These Jewish converts were commonly called conversos, New Christians, or marranos; the latter two terms were used as insults. At first, these conversions seemed an effective solution to the cultural conflict: many converso families met with social and commercial success. But eventually their success made these new Catholics unpopular with their neighbors, including some of the clergy of the Church and Spanish aristocrats competing with them for influence over the royal families. By the mid-fifteenth century, the demands of the Old Christians that the Catholic Church and the monarchy differentiate them from the conversos led to the first limpieza de sangre laws, which restricted opportunities for converts. These suspicions on the part of Christians were only heightened by the fact that some of the coerced conversions were undoubtedly insincere. Some, but not all, conversos had understandably chosen to salvage their social and commercial positions or their lives by the only option open to them, baptism and embrace of Christianity, while privately adhering to their Jewish practice and faith. Recently converted families who continued to intermarry were especially viewed with suspicion. These secret practitioners are commonly referred to as crypto-Jews or marranos.[21] The existence of crypto-Jews was a provocation for secular and ecclesiastical leaders who were already hostile toward Spain’s Jewry. For their part, the Jewish community viewed conversos with compassion, because Jewish law held that conversion under threat of violence was not necessarily legitimate. Although the Catholic Church was also officially opposed to forced conversion, under ecclesiastical law all baptisms were lawful, and once baptized, converts were not allowed to rejoin their former religion. The uncertainty over the sincerity of Jewish converts added fuel to the fire of antisemitism in fifteenth-century Spain.

Right: A signed copy of the Edict of Expulsion – The Decree of Alhambra[22]

Left: Expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 a painting by Emilio Sala Francés[23]

While the Spanish Inquisition is not the scope of this publication, it is relevant to highlight the sordid details, delightfully documented by the Spanish Government during these barbaric times, all in the name of propagating purist Christianity and the Catholic Church, in particular. The grand inquisitor acted as the head of the Inquisition in Spain. The ecclesiastical jurisdiction that he had received from the Vatican empowered him to name deputies and hear appeals. In deciding appeals, the grand inquisitor was assisted by a council of five members and by consultors. All those offices were filled by agreement between the government and the grand inquisitor. The council, especially after its reorganization during the reign of Philip II (1556–98), put the effective control of the institution more and more into the hands of the civil power. After the papacy of Clement VII (1523–34), priests and bishops were at times judged by the Inquisition. In procedure the Spanish Inquisition was much like the medieval inquisition. The first grand inquisitor in Spain was the Dominican Tomás de Torquemada; his name became synonymous with the brutality and fanaticism associated with the Inquisition. Torquemada used torture and confiscation to terrorize his victims, and his methods were the product of a time when judicial procedure was cruel by design. The sentencing of the accused took place at the auto-da-fé , Portuguese: “act of faith”, an elaborate public expression of the Inquisition’s power. The condemned were presented before a large crowd that often-included royalty, and the proceedings had a ritualized, almost festive, quality. The number of burnings at the stake during Torquemada’s tenure was exaggerated by Protestant critics of the Inquisition, but it is generally estimated to have been about 2,000.[24]

Against such a backdrop of active persecution of the Jewish community, in Spain, their synagogues were also targeted during this period. By the late Middle Ages, there were at least eleven synagogues in the city of Toledo in central Spain. Two of these, the Samuel Halevi Abulafia synagogue and the Ibn Shoshan synagogue stand only a few blocks apart in Toledo.[25]

The Synagogue of Santa María la Blanca, Spanish: Sinagoga de Santa María La Blanca, literally, the ’Synagogue of Saint Mary the White’, or Ibn Shoshan Synagogue[26] is a museum and former synagogue in Toledo, Spain[27]. Erected in the late twelfth or early thirteenth century, it is disputably considered the oldest synagogue building in Europe still standing. The building was converted to a Catholic church in the early 15th century.

The synagogue is located in the former Jewish quarter of the city, between the Monastery of San Juan de los Reyes and the Synagogue of El Transito. It is one of three preserved synagogues constructed by Jews in a Mudéjar or Moorish style under the rule of the Christian Kingdom of Castile.[28] The exact origins and original specifications of the synagogue prove difficult to place. Evidence points toward a construction date sometime in the late twelfth century or early thirteenth century CE. Supporting evidence for this dating is the structure’s architectural style, which is close to that of Almohad monuments of the twelfth century, such as the Tinmal Mosque (1149) and Kutubiyya mosque (1147).[29]

One commonly accepted opinion is that it was erected sometime around 1205, as documents from the time mention a “new”, great synagogue located in Toledo.[30] Another theory arises from a wooden tablet found in the area that describes a new structure, saying, “Its ruins were raised up in the year 4940” (CE 1180).[31] If this inscription indeed refers to the Synagogue of Santa María la Blanca, then the synagogue may in fact be a reconstruction of an existing building or a new building located on the same plot as a demolished one. One hypothesis that has been raised to explain the synagogue’s layout is that may have been taken from a preexisting mosque located on the same site.[32] Another former synagogue building in Segovia (destroyed after a fire in 1899) had a very similar layout, which suggests that more synagogues of this type may have once existed in the region.[33]

Some historians, such as Leopoldo Torres Balbás, note similarities between the plaster work in the aisles of Santa María la Blanca and the convent Las Huelgas de Burgos, which is of a later date, around 1275. According to Carol Herselle Krinsky, however, the scale and proportion of the ornamentation, the blank canvas against which the ornamentation is placed, as well as the way in which light is used in the space all correspond more closely with the twelfth-century mosques and thus with an earlier construction date.[34]

It is also somewhat unclear who might be the patron of the original synagogue, although there is some evidence for Joseph ben Meir ben Shoshan, or Yusef Abenxuxen, as the original patron. Joseph was the son of a finance minister to King Alfonso VIII of Castile and, upon his death in 1205, his epitaph mentions his having built a synagogue. Some theories suggest Joseph rebuilt the synagogue after a pogrom against Jews in Toledo. This may be the cause for the building’s irregular floor plan and again points to a late-twelfth-century construction.[35] The synagogue is a Mudéjar construction, created by Moorish architects for non-Islamic purposes. But it can also be considered one of the finest examples of Almohad architecture because of its construction elements and style. The plain white interior walls as well as the use of brick and of pillars instead of columns are characteristics of Almohad architecture.[36] There are also nuances in its architectural classification, because although it was constructed as a synagogue, its hypostyle room and the lack of a women’s gallery make it closer in character to a mosque. Though it does not have a women’s gallery today, an early twentieth century architect suggested that it did at one time have a one.[37]

As a result of the pogroms of 1391 and the anti-Jewish preaching of Vicente Ferrer, the synagogue was sacked and then appropriated by the Catholic church.[38] It was officially consecrated as a church in the early 15th century, though sources vary in stating the exact year: some cite 1401, 1405, 1410, or 1411[39]. The church was given to the Order of Calatrava.[40] Its present name, Santa Maria la Blanca (‘Saint Mary the White’) dates from this time and comes from an effigy of Mary that was kept inside.[41] Between 1550 and 1556 three small apses were added to the back of the building to serve as chapels, still visible today. They are designed in a Renaissance style and are attributed to Alonso de Covarrubias.[42]

The building was later used as a military barracks, a warehouse, and a dancehall.[43] The author visited the former synagogue in Toledo and was struck by sadness, when the tour guide informed the tourists that the Spanish monarchy, during the reign of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, decreed at one stage that the synagogue be converted to a piggery, as a sign of supreme insult and total defilement with desecration of the hallowed precincts of a sacrosanct place of worship of Judaism. This is the level of arrogance of the Queen Isabella of the combined kingdoms of Aragon and Spain, had stooped to, in order to denigrate the Jews of Toledo. Manacles were also installed on the outer, south facing wall, of this same synagogue, when converted to a cathedral, exposed to bright sun, to tie up the crypto Jews, when discovered by the Inquisitors.

The building was eventually declared a national memorial site and restored in 1856. The government restored Santa María la Blanca to the care of the archdiocese through a local parish in 1929. Today, it is a museum and tourist attraction. The building is surrounded by a courtyard. This courtyard served as a place for the people to congregate before and after prayer services and also held the different communal institutions. The Rabbi’s residence, a ritual bath, a study hall, and other things the community may have invested in were all built in this courtyard to give the Jewish community a central place for care of their spiritual needs.[44]

Over the years there have been many official requests for the formal return of the structure, albeit modified, to the Jewish Community, where it rightfully belongs. In 2013 the Jewish community of Toledo asked the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Toledo, Braulio Rodríguez Plaza, to transfer ownership and custodianship of the building to them.[45] The archbishop met twice with Isaac Querub, president of Spain’s Federation of Jewish Communities, who said that there was, no Jewish community in Toledo today but that the federation was not looking to reclaim Santa María la Blanca as a place of worship but a “symbolic gesture”.[46] There is no judicial recourse because the modern Jewish community are not direct descendants of the original owners.[47] The building, the third most visited historic monument in Toledo, is presently a museum and is not used for any religious ceremonies. Since 2013, the archdiocese has spent almost €800,000 (£685,000) on conserving the building.[48]

The Bottom Line, is that during the Spanish Inquisition, 530 years ago, to date, the devout members of the Jewish Community in Spain made impossible choice, between religion, life and Death. Many Jews were brutally tortured and were martyred bravely. Others were part of the second exodus reminiscent of Biblical proportions. While other became crypto Jews, but these individuals were also relentlessly hunted and subjected to inhuman torture and execution. Their punishment was much more intense and horrific. Not only did the Jewish community were personally persecuted but their hallowed synagogues were defiled and brazenly desecrated by the fanatical members of the Catholic Church. It is estimated that presently, some 200 million people may be descendants of the Spanish and Portuguese communities forced to convert to Christianity.

According Ashley Perry (Perez), president of Reconectar, a project that focuses on “facilitating the reconnection of descendants of the Spanish and Portuguese Jewish communities with the Jewish people,” there could be some 200 million people today that have Jewish DNA. Genetic research released previously, found that 25% of Hispanics and Latinos have Jewish DNA. Perry, who is also the Director-General of the Knesset Caucus for the Reconnection with the Bnei Anousim, told The Jerusalem Post that he would argue that the expulsion of the Jews from Spain and later Portugal “is the most significant Jewish date in history since the fall of the Second Temple. It was the game-changing moment.”[49]

The sordid saga of these synagogues, repurposed into cathedrals, ironically designed in an Islamic architectural style and built by an Islamic person for use by Jews, as the “People of the Book”, has been defiled by the Christians, also of the same Abrahamic faith, causing great loss of life and peace disruption, over the past five centuries, with no resolution of the ongoing anti-Semitism, as well as conflict and reconciliation, in sight. Perhaps the future might be different, indeed, “if the Lord willeth”.

One of the Renaissance apses (1550–1556), situated over the former location of the ark in The Synagogue of Santa María la Blanca in Toledo, Spain. Note the fusion of the architectures of the three, main Abrahamic Faiths: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. [50]

[1] Personal quote by the author, November 2022.

[2] https://images.jpost.com/image/upload/f_auto,fl_lossy/t_JD_ArticleMainImageFaceDetect/444215

[3] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=04f19e401bd38d7fJmltdHM9MTY3MDAyNTYwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTE3MA&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&psq=Holocaust&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvVGhlX0hvbG9jYXVzdA&ntb=1

[4] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=8dc44ea52a1cf4b7JmltdHM9MTY3MDAyNTYwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTE3Mw&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&psq=nazi+party+definition&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvTmF6aV9QYXJ0eQ&ntb=1

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Exodus#:~:text=In%20the%20Bible%2C%20the%20Exodus%20is%20frequently%20mentioned,the%20Jewish%20holidays%20of%20Passover%2C%20Shavuot%2C%20and%20Sukkot.

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Exodus#CITEREFRedmount2001

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Exodus#CITEREFSparks2010

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:1867_Edward_Poynter_-_Israel_in_Egypt.jpg

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Exodus#CITEREFBaden2019

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Exodus#CITEREFTigay2004

[11] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b7/A_Seder_table_setting.jpg/300px-A_Seder_table_setting.jpg

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Exodus#CITEREFBerlinBrettler2004

[13] https://www.jpost.com/diaspora/spanish-inquisition-527-years-ago-jews-in-spain-made-impossible-choice-597298

[14] Data for executions for witchcraft: Levack, Brian P. (199). The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe (Second ed.). London and New York: Longman. ISBN 9780582080690. OCLC 30154582.

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_Inquisition#:~:text=Hans%2DJ%C3%BCrgen%20Prien%20(21%20November%202012).%20Christianity%20in%20Latin%20America%3A%20Revised%20and%20Expanded%20Edition.%20BRILL.%20p.%C2%A011.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D90%2D04%2D22262%2D5.

[16] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=bf0995755639a16fJmltdHM9MTY3MDAyNTYwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTE5NQ&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&psq=Alhambra+Decree&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9lbi53aWtpcGVkaWEub3JnL3dpa2kvQWxoYW1icmFfRGVjcmVl&ntb=1

[17] Gerber, Jane (1994). The Jews of Spain: A History of the Sephardic Experience. New York: The Free Press. pp. 1–144. ISBN 978-0029115749.

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mar%C3%ADa_Rosa_Menocal

[19] http://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/ha-nagid.asp

[20] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alhambra_Decree#Background:~:text=Kaye%2C%20Alexander%3B%20Meyers%2C%20David%2C%20eds.%20(2014).%20The%20Faith%20of%20the%20Fallen%20Jews%3A%20Yosef%20Hayim%20Yerushalmi%20and%20the%20Writing%20of%20Jewish%20History%20(The%20Tauber%20Institute%20Series%20for%20the%20Study%20of%20European%20Jewry).%20Massachusetts%3A%20Brandeis%20University%20Press.%20pp.%C2%A0252%E2%80%93253.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D1611684872.

[21] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources/978-0029115749

[22] ttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alhambra_Decree#/media/File:Alhambra_Decree.jpg

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Expulsi%C3%B3n_de_los_jud%C3%ADos.jpg

[24] https://www.britannica.com/topic/Spanish-Inquisition

[25] https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=3dca0390168b21d7JmltdHM9MTY3MDAyNTYwMCZpZ3VpZD0zOWJhOTNjNy03Mjc4LTYwNTctMmY5Mi05OGMyNzM1MjYxM2YmaW5zaWQ9NTE3Ng&ptn=3&hsh=3&fclid=39ba93c7-7278-6057-2f92-98c27352613f&psq=toledo+synagogues&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly9zbWFydGhpc3Rvcnkub3JnL3N5bmFnb2d1ZXMtdG9sZWRvLXNwYWluLw&ntb=1

[26] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synagogue_of_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca#:~:text=Q%C3%B4%C7%A7man%2DAppel%2C%20Qa%E1%B9%ADr%C3%AEn%20(2004).%20Jewish%20Book%20Art%20Between%20Islam%20and%20Christianity%3A%20The%20Decoration%20of%20Hebrew%20Bibles%20in%20Medieval%20Spain.%20Brill.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D90%2D04%2D13789%2D9.

[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synagogue_of_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca#:~:text=Hourihane%2C%20Colum%2C%20ed.%20(2012).%20%22Jewish%20architecture%22.%20The%20Grove%20Encyclopedia%20of%20Medieval%20Art%20and%20Architecture.%20Oxford%20University%20Press.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D0%2D19%2D539536%2D5.

[28] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synagogue_of_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca#:~:text=Mann%2C%20Vivian%20B.%20(2019).%20%22Synagogues%20of%20Spain%20and%20Portugal%20during%20the%20Middle%20Ages%22.%20In%20Fine%2C%20Steven%20(ed.).%20Jewish%20Religious%20Architecture%3A%20From%20Biblical%20Israel%20to%20Modern%20Judaism.%20Brill.%20pp.%C2%A0151%E2%80%93168.%20doi%3A10.1163/9789004370098_010.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D90%2D04%2D37009%2D8.%20S2CID%C2%A0210627440.

[29] https://books.google.com/books?id=uv1c0gkDgLsC&q=la+blanca

[30] https://books.google.com/books?id=zXF9DAAAQBAJ&dq=synagogue+la+blanca+1205&pg=PA462

[31] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synagogue_of_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca#:~:text=Krinsky%2C%20Carol%20Herselle%20(1996)%20%5B1985%5D.%20Synagogues%20of%20Europe%3A%20Architecture%2C%20History%2C%20Meaning.%20Dover%20Publications.%20pp.%C2%A0331%E2%80%93335.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D0%2D486%2D29078%2D2.

[32] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synagogue_of_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca#:~:text=Mann%2C%20Vivian%20B.%20(2017).%20%22Decorating%20Synagogues%20in%20the%20Sephardi%20Diaspora%3A%20The%20Role%20of%20Tradition%22.%20In%20Gharipour%2C%20Mohammad%20(ed.).%20Synagogues%20in%20the%20Islamic%20World%3A%20Architecture%2C%20Design%2C%20and%20Identity.%20Edinburgh%20University%20Press.%20pp.%C2%A0212%E2%80%93214.%20ISBN%C2%A09781474468435.

[33] Mann, Vivian B. (2017). “Decorating Synagogues in the Sephardi Diaspora: The Role of Tradition”. In Gharipour, Mohammad (ed.). Synagogues in the Islamic World: Architecture, Design, and Identity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 212–214. ISBN 9781474468435.

[34] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synagogue_of_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca#:~:text=Krinsky%2C%20Carol%20Herselle%20(1996)%20%5B1985%5D.%20Synagogues%20of%20Europe%3A%20Architecture%2C%20History%2C%20Meaning.%20Dover%20Publications.%20pp.%C2%A0331%E2%80%93335.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D0%2D486%2D29078%2D2.

[35] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synagogue_of_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca

[36] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synagogue_of_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca#:~:text=Dodds%2C%20Jerrilyn%3B%20Mann%2C%20Vivian%20%26%20Glick%2C%20Thomas%2C%20eds.%20Convivencia%3A%20Jews%2C%20Muslims%2C%20and%20Christians%20in%20medieval%20Spain%20(New%20York%C2%A0%3A%20G.%20Braziller%20in%20association%20with%20the%20Jewish%20Museum%2C%201992)

[37] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synagogue_of_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca#:~:text=Czekelius%2C%20D.%20%22Antiquas%20Sinagogas%20de%20Espana%22%20Arquitectura%2012%2C%20no.%20150%20(Oct.%201931)

[38] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synagogue_of_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca#:~:text=Simon%2C%20Sherry%20(2019).%20Translation%20Sites%3A%20A%20Field%20Guide.%20Routledge.%20p.%C2%A049.

[39] Simon, Sherry (2019). Translation Sites: A Field Guide. Routledge. p. 49.

[40] https://www.qantara-med.org/public/show_document.php?do_id=1349&lang=en

[41] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synagogue_of_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca#:~:text=Franco%2C%20%C3%81ngela.%20%22Synagogue%20of%20Santa%20Maria%20la%20Blanca%22.%20Discover%20Islamic%20Art%2C%20Museum%20With%20No%20Frontiers.%20Retrieved%202022%2D03%2D10.

[42] “Qantara – Synagogue of Santa Maria la Blanca”. www.qantara-med.org. Retrieved 2022-03-10.

[43] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special:BookSources/978-1-56171-081-2

[44] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synagogue_of_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca#:~:text=Meir%2C%20Ben%2DDov%20(2009).%20The%20Golden%20Age%3A%20Synagogues%20of%20Spain%20in%20History%20and%20Architecture%20(1st%C2%A0ed.).%20Jerusalem%3A%20Urim.%20ISBN%C2%A0978%2D9655240184.%20OCLC%C2%A0294885916.

[45] http://www.timesofisrael.com/spanish-jews-ask-catholics-to-return-ancient-synagogue/

[46] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/mar/08/we-want-action-call-to-return-former-toledo-synagogue-to-jewish-community

[47] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synagogue_of_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca#:~:text=Colom%C3%A9%2C%20Jordi%20P%C3%A9rez%20(2017%2D02%2D19).%20%22La%20sinagoga%20de%20la%20discordia%22.%20EL%20PA%C3%8DS%20(in%20Spanish).%20Retrieved%202017%2D12%2D31.

[48] Jones, Sam. “Call to return former Toledo synagogue to Jewish community”, The Guardian, March 8, 2017

[49] https://www.jpost.com/diaspora/spanish-inquisition-527-years-ago-jews-in-spain-made-impossible-choice-597298#:~:text=According%20Ashley%20Perry,game%2Dchanging%20moment.%E2%80%9D

[50] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synagogue_of_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca#/media/File:Sinagoga_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Blanca,_Toledo_(6158249052).jpg

______________________________________________

READ: PART 1 – PART 2 – PART 3

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Professor G. Hoosen M. Vawda (Bsc; MBChB; PhD.Wits) is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment.

Director: Glastonbury Medical Research Centre; Community Health and Indigent Programme Services; Body Donor Foundation SA.

Principal Investigator: Multinational Clinical Trials

Consultant: Medical and General Research Ethics; Internal Medicine and Clinical Psychiatry:UKZN, Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine

Executive Member: Inter Religious Council KZN SA

Public Liaison: Medical Misadventures

Activism: Justice for All

Email: vawda@ukzn.ac.za

Tags: Christianity, Conflict, History, Islam, Mosque, Religion, Spain

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 5 Dec 2022.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: Peace Disruptors–The Conversion and Repurposing of Places of Worship (Part 4): Synagogues Defiled by Spanish Monarchy, is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.