A Distant Flickering Light: The Hibakusha Peace Movement (Part 1)

SPECIAL FEATURE, CONFLICT RESOLUTION - MEDIATION, TRANSCEND MEMBERS, HUMAN RIGHTS, ANGLO AMERICA, ASIA--PACIFIC, MILITARISM, WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION, 6 Aug 2018

Robert Kowalczyk – TRANSCEND Media Service

[The United States detonated two nuclear weapons over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, respectively.]

An Interview with Mrs. Koko Kondo, The Tanimoto Peace Foundation

Conducted in Kobe, Japan on 27 Jul 2018

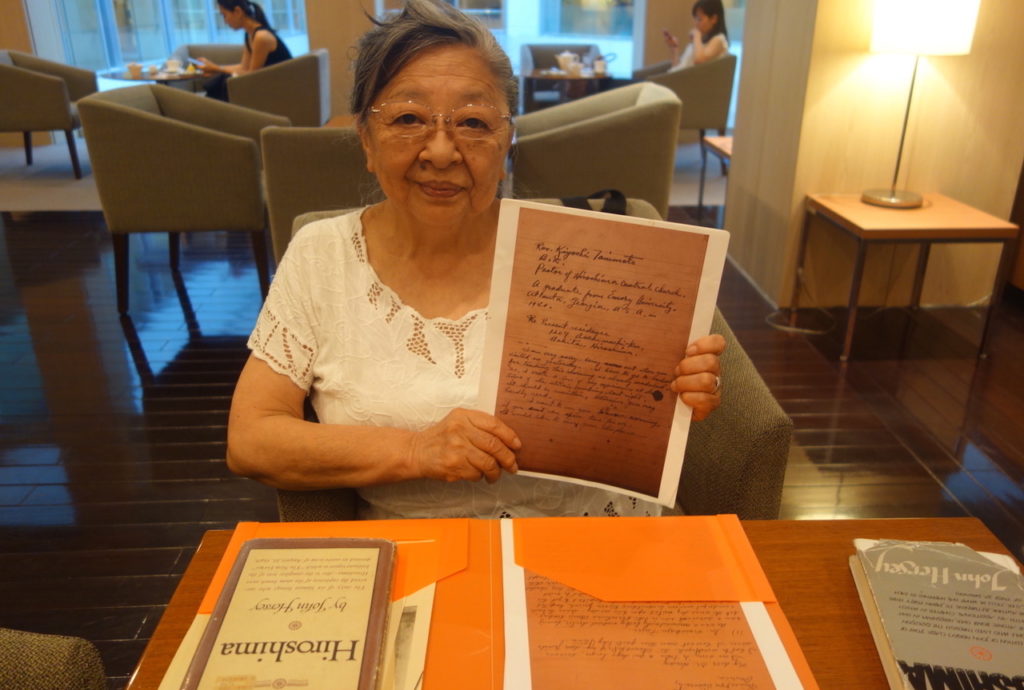

Mrs. Koko Kondo showing the manuscript written by her father, Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto, that inspired John Hersey’s classic, Hiroshima.

Do you think the Hibakusha are still important?

They are still very important. This is because those individuals of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are the only humans who have ever experienced and survived a nuclear bombing. That is a fact. They are the ones who know. Only they. That’s why they are so important. But now, they are quite elderly and someday they will no longer be able to relate their own experiences. That is another important fact.

The other day some students said to me, “Oh, we’ve heard these same kind of stories before.” And I replied, “Of course. Everybody in Hiroshima and Nagasaki went through them, including me. But each one of them had a different experience and each of us has had a different life. And now all of them feel a need to express that experience to others and to the world. If you don’t listen to them now, you may never be able to hear them again. So that’s why it’s important.”

Finally, some students said, “We agree with you Mrs. Kondo.”

Sometimes I have to hit them in their heads to wake them up.

Some say that there will never be other Hibakusha, because if there are, there will be no one left to listen to them. Do you agree?

Yes, I do. We first generation Hibakusha are very aware of that.

One thing is for sure. We who have experienced the nuclear bombings have tried so hard to relate our experiences for one reason only — none of us can bear the thought of a third one.

That one moment, the moment that the nuclear bomb exploded, you carry that one moment with you for the rest of your life.

I remember near the end of my father’s life, a time when he was becoming quite weak. There was the sound of a clock ticking in the room, gatchi, gatchi, gatchi . . . My father asked, “What is that sound?” He was told it was the clock in the room. And my father replied, “Oh, I hope it’s not the bomb.”

So, you see, he was always thinking about the bomb, from the time of the explosion until nearly the time of his death in 1986, more than 41 years later.

It was the one moment in his life he would always remember.

How about your own memory and thoughts while you were young?

When I was very young, for many years my parents told me, “Koko, you were able to survive. You’re the only baby to survive in our neighborhood. So you must work for peace. You must work for Hiroshima.”

But I told them, “No. Not me.” For a long time, I adamantly refused.

Then finally, when I was forty, it was the time of my father’s last sermon at his church. Of course, at first he read and talked about the Bible, but then he started to talk about why he was so involved with the Hiroshima survivors, the Hibakusha. And for the first time he expressed publicly what he felt on August 6th of 1945. I had never heard him talk about it before, his own experience of that day. The three of us, who were there, simply never talked about it with each other. Most Hibakusha families, I believe, were the same.

Well, as my father related that day, when he saw the flash over the city from the mountain and then fire everywhere, the first thing that came into his mind was, “what’s happened to my daughter, what’s happened to my wife, what’s happened to my church members, what’s happened to my neighbors.” And so he rushed down into the city. As he ran past the dead and the dying, the countless victims, so many of them were asking for his help. “Help! Help!” so many cried. Being a minister, of course he wanted to help. But he told us on that day that the first thing that came into his mind was, “What has happened to my family, my daughter, my wife?”

Then he told us that he suddenly asked himself, “What kind of a self-centered man am I? I’m only thinking about my own, not all of these that I’m passing by.” Being a minister of the church, he felt a strong self-resentment growing inside, and along with that a feeling that his thoughts were purely egoistic. He then told the group listening to him, including me, that his deep self-resentment made him become an activist in the Hibakusha peace movement.

And just then, as my father spoke, I realized I had been doing the same thing. Thinking of myself rather than of others. I believe it was a day that changed my life. I too would begin to speak for the Hibakusha, to express their messages of peace, of humble acceptance without blame, and of course of warning. It was a day when my life changed and my independent peace activism began.

That’s very fine. Can you please give me an example of Reverend Tanimoto’s missions of telling the American people about the atomic bombings?

Okay, I have it written here. These are some details from my father’s records from his first trip to the U.S. after the war. He kept records of everything. Please remember this is just one time of many such trips.

From September 1948 until January 1950, for about 15 months, he went to 31 states, 256 cities, 472 churches, schools and other locations, and gave 582 lectures to which about 160,000 people listened, while he traveled over 65,000 miles. He wrote each detail of those many trips, so his records are complete.

Over the years, I followed his lead, constantly traveling and lecturing, but I never counted my trips in such detail as he did during that time.

Then one could easily say that your father was one of if not the initiator of the Hibakusha Peace Movement and was succeeded by his daughter.

Perhaps, but I wouldn’t want to express that myself. We simply have done and continue to do what we can.

Do you have any other memories of your early years, experiences that may have affected you in some way?

When I was a small child, maybe three or four years old, young teen-age girls used to come to my father’s church and they were so nice to me. I remember they would sometimes gently comb my hair. But I could never look at their faces because they were so deformed. I just wanted to look at the combs they were using, nothing else. But, of course, I saw their hands and on many of them the skin had melted and the bones were deformed.

And when I shyly and slowly looked up, I saw that their faces also had been terribly disfigured. But even as a little child, I did not ask those girls, “What happened to your face? What happened to your hands?” I knew it was not the right thing to ask even at that young age. But I saw, and I felt their pain.

I also listened to their talk and as I listened I suddenly realized that they were victims of the atomic bomb. You see, the realization of what had happened was coming to me and then disappearing again when I was so young. People did not talk about it, not even my parents. Everyone was so busy and it was not something to talk about. There was too much to do.

So the memory of those poor young girls stays with me.

You mean, you never talked about the bomb even with your parents?

No, not really. Of course we knew about it, we were deeply aware of it, but we never discussed it in any way. I knew I was a survivor, but I didn’t know how I survived, and I never asked my parents. We all kept these memories deep inside ourselves.

Then, when I was about 40, one day my mother said to me, “I better tell you what happened to us.”

That’s about the same time as your father’s last lecture at the church, isn’t it?

Yes, in perhaps the same year.

Then everything was starting to come together for you including things that had been suppressed by you and your parents.

Yes. What had been abstract or vague was beginning to become clear.

I remember my mother and I sat on the couch and she filled me in on some of the things that were missing from my memories. That was the first time, face to face. Of course, I knew the basics, but this was somewhat different. This was my mother telling me her story. I didn’t ask any questions. I just quietly listened to her talk.

Then for 40 years your family never talked about the bombing openly?

No. Nothing. Never.

Of course we sometimes would talk when we had guests coming from overseas, but that was very different. That was a public talk. It was quite different than family talk, which we did not do until that time when I was 40, both through my father’s speech at the church and my mother’s revealing talk on the couch.

Again, I believe this was common among many Hibakusha families. It was something that we had all experienced at a very deep level. Not something that can be easily talked about, perhaps especially among family members.

Who besides your father has influenced your life’s path?

Yes. That’s a good question, and one that I can easily answer. Whenever I have been asked to give a talk, I have often told my story of Captain Robert Lewis, the co-pilot of the Engola Gay. That was the B-29 that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Of course, as many know, in 1955, my father was a guest on an American television program, This Is Your Life. It was very popular and many famous people, such as actors, artists or musicians, appeared on it. And ten years after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, my father was the show’s guest.

The main feature of the show was to tell the story of a man or woman who had contributed their life to making the world a better place, in one way or another. And the way the television host would do this was by suddenly introducing various people connected with the guest’s life, to first surprise the guest and then to talk with him or her on the show about their shared memories.

Aside from my father’s colleagues and friends, including members of one of his former congregations in the U.S., our whole family, my mother, I and my two brothers and sister, were secretly invited and brought all the way from Japan to surprise my father. All the surprise guests were kept in deep secrecy until they would suddenly come onto the stage into the television screens.

One of those guests was Captain Robert Lewis.

I was ten years old at that time and so, of course, I was in a kind of dream, waiting with my mother and brothers and sister to appear with the other guests as a big surprise for my father. And while standing on the back stage with my family I saw three other people at the other end of the stage. I knew two of them were close of my father so I was so happy to see them. But I didn’t know the third person standing next to them.

Since I was a fifth grader at the time and very curious, I asked my mother, “Who is that man over there?” But she wouldn’t answer me. If she didn’t know who he was, she certainly would have answered me by saying something like, “Koko, I’m sorry. I don’t know.” She knew who it was but thought it better to not tell me. She knew her daughter very well.

However, as we waited longer for the program to begin, she eventually decided that she had better tell me before we went in front of the cameras, just in case, as she understood my temper.

So she said, “Koko. That is Captain Robert Lewis, the co-pilot of the Enola Gay.”

Hearing that, I remembered those girls who came to visit me at the church back in those years after the war. They would say, “Koko-chan. Koko-chan.” They were so sweet. They treated me like their own younger sister. And I remember as they talked about the bomb, I began thinking at that very young age, someday I would find the person on that B-29 bomber and when I did I would give him a punch or a bite or a kick.

That’s what I can do and that’s what I will do, I thought.

I knew that if my parents would find out my thoughts, they would give me a long speech about the Bible and why that kind of thinking was wrong. So I never told them. I just kept it deep inside waiting for the time when I could do it. Always thinking, “I’m definitely going to do it.”

So, what happened? Did you kick him, or bite him, or punch him?

Well, I knew I couldn’t do that. That was not the right thing to do at that time, of course. So I just stared at him thinking, “He’s the bad guy. And I’m the hero.”

Right?

Right, of course.

As we waited for our family to go on stage, I did not understand most of the onversation as the guests appeared one by one. However, I did understand when Ralph Edwards, the host of the show, asked Robert Lewis, “How did you feel when you dropped the bomb?”

And Captain Lewis replied that they dropped the bomb at 8:15 am and then quickly flew away due to the danger of the explosion. But the plane soon had to return to see the results of the bombing. Lewis said that he looked down and the city of Hiroshima had completely disappeared. And then he said that he wrote a note to his mother, “My God, what have we done.”

And from his eyes, live on that stage, the tears escaped.

When I saw that, I thought, “He’s not a monster. He’s a human being.”

I looked inside of myself and felt so sorry. I did not know anything about this man. And I realized that I had so much evil inside myself. And then I suddenly understood that if I hate, I should hate war itself, not this person.

Did you have a chance to talk with Captain Lewis?

Well, after the show we were all still on the stage and I don’t know why I did it but I walked like a shy crab across the stage and touched his hand. That was the moment I wanted to say, “I’m sorry.” But, of course, I could not speak.

Captain Lewis immediately recognized what I was trying to convey and he gently held my hand and turned us both to the audience that was still there. That is one of the most important moments in my life.

Did you ever meet him again?

In my junior year in a U.S. college, about ten years later, I suddenly wanted to see him. I just wanted to say, “Thank you. It’s because of you, sir, that little Koko changed.”

But I couldn’t find him. So I asked my father’s friends to find him and they did. They told me, “I’m sorry, Koko. Robert Lewis is in a hospital. A mental hospital.”

I was a poor student and the U.S. is such a big country, so I didn’t go to visit him. But I really wanted to meet him to express my sincere thoughts, and since I was so busy at school, I didn’t think about him after that.

I came back to Japan and five and a half years passed. Then one day, I opened the newspaper and found out that he had passed away. I felt deep regret that we had not met again.

And a few years following that I saw an article where a psychotherapist was showing a sculpture that Robert Lewis had made while at the mental hospital. It was of a mushroom cloud with one tear.

That sculpture is somewhere in this world and someday I hope that I will be able to see it. So for Captain Lewis, I knew that he also suffered and I learned that in war both sides suffer. And now, whenever I meet with young people from East and Southeast Asia, I first have to say, “I’m sorry for what Japan did.”

In Hiroshima City there is a cenotaph dedicated to the victims of the nuclear bombing. On that cenotaph there is an inscription, “Rest in peace, we shall never repeat our mistake.” However, Hiroshima City translated that in English to, “Rest in peace. We shall never repeat our evil.”

But to me, evil is too strong a word. The word in Japanese is “ayamachi” which we usually translate as “mistake”. Although others may think that mistake is too light, I feel that the word evil is far too strong.

Human beings are not evil, what we do certainly may be, but it is not who we are.

Don’t you agree?

Yes. Thank you very much for this interview, Koko.

You’re very welcome.

*********************************

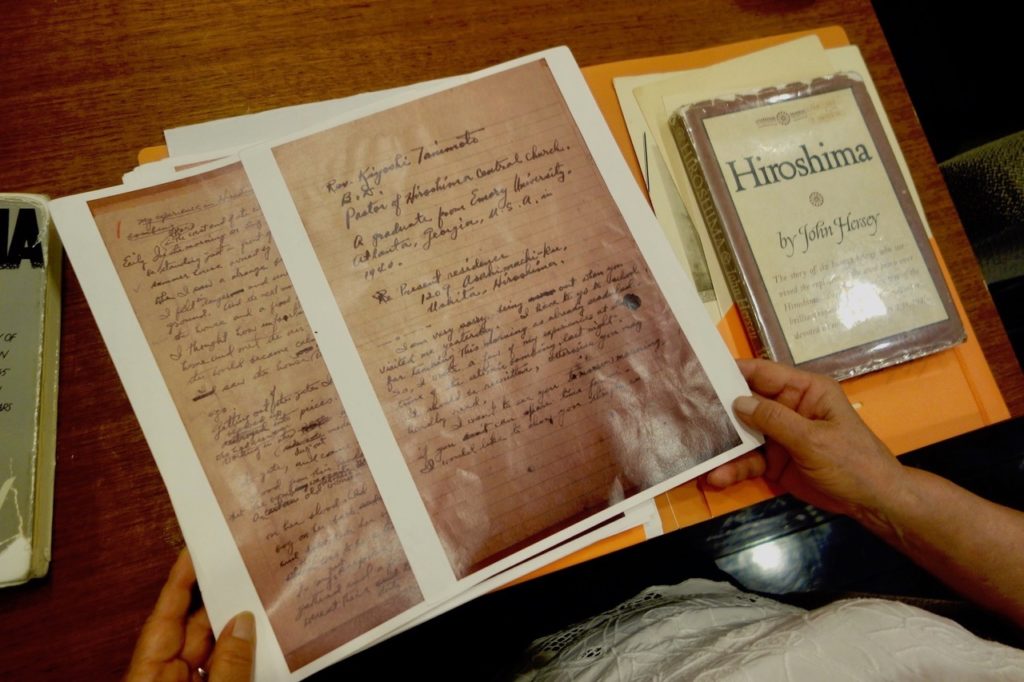

Interviewer’s note: It is important to point out the circumstances behind the documents that Mrs. Koko Kondo shows in the image taken at the beginning of this interview. The pages of the document that Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto wrote are copies of the actually documents kept in the Yale University Library. Cannon Hersey, John Hersey’s grandson who had visited the library, sent the copies to Mrs. Koko Kondo in 2016.

When John Hersey first went to Hiroshima City in January of 1946, just five months after the bombing, he had already heard about Reverend Tanimoto’s work and knew that he would be an important individual to call upon during his stay there. He visited the Tanimoto family’s dwelling twice, but Mr. Tanimoto was not at home since he was constantly working to help others in the still devastated community.

When Mr. Tanimoto returned and found out that Mr. Hersey had called on him to ask about his experiences on the day of the bombing, he was very troubled that he may have missed an opportunity to express what he knew and that Mr. Hersey might never come again, that he stayed up all night and wrote many pages of the long letter. As can be seen above, he didn’t care about scribbling out mistakes. There simply wasn’t enough time. He felt he had to finish by morning when John Hersey said he would visit again.

Having had a look at the documents before this interview, it is clear to this writer that Mr. Tanimoto had presented Mr. Hersey with inspiring words that he later transformed into his classic of peace journalism, Hiroshima.

With that fact in mind, and with all of what has been read about Mr. Tanimoto through Hiroshima as it appeared in full in The New Yorker magazine in 1946 and in a sequel, entitled Hiroshima: The Aftermath. published in 1985, it is obvious that Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto was the incipient and most insistent voice of the Hibakusha Peace Movement.

Our world owes both of these men a great debt along with all the Hibakusha who have struggled for these many years to express the inexpressible.

Perhaps it is they who have kept us safe until now.

What has kept the world safe from the bomb since 1945 has not been deterrence, in the sense of fear of specific weapons, so much as it’s been memory. The memory of what happened at Hiroshima (and Nagasaki).

~~ John Hersey

_________________________________________

Robert Kowalczyk is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment. He is former Professor and Department Chair of the Department of Intercultural Studies in the School of Art, Literature and Cultural Studies of Kindai University, Osaka, Japan. Robert has coordinated a wide variety of projects in the intercultural field, and is currently the International Coordinator of Peace Mask Project. He has also worked in cultural documentary photography and has portfolios of images from Korea, Japan, China, Russia and other countries. He has been a frequent contributor to Kyoto Journal. Contact can be made through his website portfolio: robertkowalczyk.zenfolio.com.

Robert Kowalczyk is a member of the TRANSCEND Network for Peace Development Environment. He is former Professor and Department Chair of the Department of Intercultural Studies in the School of Art, Literature and Cultural Studies of Kindai University, Osaka, Japan. Robert has coordinated a wide variety of projects in the intercultural field, and is currently the International Coordinator of Peace Mask Project. He has also worked in cultural documentary photography and has portfolios of images from Korea, Japan, China, Russia and other countries. He has been a frequent contributor to Kyoto Journal. Contact can be made through his website portfolio: robertkowalczyk.zenfolio.com.

This article originally appeared on Transcend Media Service (TMS) on 6 Aug 2018.

Anticopyright: Editorials and articles originated on TMS may be freely reprinted, disseminated, translated and used as background material, provided an acknowledgement and link to the source, TMS: A Distant Flickering Light: The Hibakusha Peace Movement (Part 1), is included. Thank you.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to TMS to join the growing list of TMS Supporters.

This work is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

11 Responses to “A Distant Flickering Light: The Hibakusha Peace Movement (Part 1)”

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

SPECIAL FEATURE:

- Genocide in Pictures: Worth a Trillion Words

- Genocide in Pictures: Worth a Trillion Words

- Genocide in Pictures: Worth a Trillion Words

CONFLICT RESOLUTION - MEDIATION:

- Nonkilling Conflict Resolution and Nuclear Conflict

- Ho'oponopono: The Hawaiian Method of Conflict Resolution

- Spain’s Prime Minister Leads the EU’s Rapprochement with China Despite Pressure from Washington

TRANSCEND MEMBERS:

- Spirit of Compassion: The Dalai Lama at 90

- Boosting "Defence" Expenditure above 10% of GDP

- The Extermination and Ethnic Cleansing in the Gaza Strip Is Reaching Unprecedented Cruelty

HUMAN RIGHTS:

- US “Relocates” Iraqi Refugee to Rwanda via New Diplomatic Arrangement

- How the Human Rights Industry Manufactures Consent for “Regime Change”

- Genocide Emergency: Gaza and the West Bank 2024

ANGLO AMERICA:

- Feeding the Warfare State

- Washington Green-Lights $30M for Gaza Aid Scheme Tied to Mass Killings of Palestinians

- War with Iran: We Are Opening Pandora's Box

ASIA--PACIFIC:

- Nepal: Proto-Nationalism Entrapped in the Musical Chair Circle of Political Parties and Floundering Economy

- South Korea's Biosecurity Is Safe, Thanks to Russia

- India and Pakistan: Freedom Lost but Animosity Flourishes

MILITARISM:

- The Transatlantic Split Myth: How U.S.-Europe Militarization Thrives behind the Rhetoric

- Mapping Militarism 2025

- The Limitations of Military Might

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION:

For your reference:

– Avoiding Nuclear War—A Discussion with the Mayor of Hiroshima: https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/06/11/avoiding-nuclear-war-discussion-with-mayor-of-hiroshima-event-6912

– What is Peace to You? – One step towards peace from Nagasaki- : http://www.n-junshin.ac.jp/univ/profile/What_is_Peace_to_You.pdf

I lived in Nagasaki. At that time I wrote a poem (in English) on the atomic bomb attack. Later, Hitoshi Motoshima, the-then mayor of Nagasaki, informed me that he decided to exhibit the poem at the Nagasaki Atomic Memorial Museum. Also see “Fr. George Zabelka’s Message for Peace”: https://www.transcend.org/tms/2014/08/fr-george-zabelkas-message-for-peace/

May peace be with everyone in the world.

This is an incredible interview! Robert Kowalczyk deftly coaxes Mrs Koko Kondo to tell her family’s story of that horrid day through the eyes of a child (herself); and with the understanding of an adolescent (herself); and with the reflections of a 40-year old woman (herself); and now, in her later years, with honed wisdom, empathy and sympathy for all the victims of human folly, madness, treachery and suffering. Mrs. Kondo’s final declaration is a testament to what the best of us may be, what the Great Teachers have taught for millennia:

“Human beings are not evil, what we do certainly may be, but it is not who we are.”

It is astonishing and inspiring that a woman who lived through so much has held fast to her father’s teaching, and finds it possible to forgive–even the co-pilot of the plane that dropped the bomb!

Grateful acknowledgment to Robert Kowalczyk for casting light on the work of Reverend Tanimoto and his daughter, Mrs. Kondo. Grateful acknowledgment to all the Hibakusha who have bravely told their stories and worked for peace and healing in in our fractured world.

I will do my best to disseminate this through my channels; and I hope others will, too.

I am not sure whether political leaders have really learned lessons from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, including from those testimonies of hibakushas, for instance. If they learned, what lessons?

– Yes, they learned. In fact, there has been no nuclear war after Hiroshima and Nagasaki to this date. The more relevant people, such as Mrs. Kondo, speak up, the more the world knows about the tragic effect of the nuclear weapons. (Unfortunately, after more than seventy years, the first generation hibakushas are perishing. The above interview is, thus, very important and precious. In addition, be aware that in her interview, Mrs. Kondo chooses her words very carefully.)

– No, they didn’t. “United States nuclear weapons were stored secretly at bases throughout Japan following World War II. Secret agreements between the two governments allowed nuclear weapons to remain in Japan until 1972, to move through Japanese territory, and for the return of the weapons in time of emergency.” U.S. nuclear weapons in Japan: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/U.S._nuclear_weapons_in_Japan ; and/or “Donald Trump’s plan for a more muscular US nuclear posture got a ringing endorsement from the increasingly right-wing government of Japan. Not long after the Trump administration released its Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) in early February, Foreign Minister Taro Kono said he “highly appreciates” the new approach to US nuclear weapons policy, including the emphasis on low-yield nuclear options the United States and Japan can rely on to respond to non-nuclear threats. ” Nuclear Hawks Take the Reins in Tokyo: https://allthingsnuclear.org/gkulacki/nuclear-hawks-take-the-reins-in-tokyo What did political leaders of the United States and Japan learn from Hiroshima/Nagasaki? No lessons from history? So, one day in the future, the untold tragic history will repeat itself?

One thing to be added here: Citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were vitctims of the atomic bomb attacks. On the other hand, Japanese in general should never forget what their military forces did during and even before WWII. “Horrific Japanese Crimes in WWII That History Forgot”: https://m.ranker.com/list/japanese-wwii-war-crimes/mel-judson These war crimes were committed by the Japanese military forces, not by the citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Nonetheless, if Japanese emphasize theie victimized aspect of WWII, and if they do not refer to theie offensive aspect of WWII, such attitude will never bring about a genuine and permanent peace to Asia. As Japanese never forget the two atomic bomb attacks, Japan’s neighbors also never forget, for example: “Kate Basco: the japanese did insane things to our people in the philippines in the war, they Raped girls, opened and sliced their Bodies and take their intestines and Brains out… they also got many women pregnant, and when they find out about it, they kill them.” https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=MDaiQ9n5wEM

Dear Satoshi Ashikaga,

Thank you for your comments on the article with Mrs. Koko Kondo of The Tanimoto Peace Foundation.

My disagreement with what you have written is that it often runs against the spirit of Mrs. Kondo’s story.

One does not need to yet once again point fingers of accusation, particularly with sensationalist quotes such as that by Kate Bosco, which only add more fuel to the kindling fires of hate and distrust which naturally lead to war.

As M.K. Gandhi might comment, you are only adding members to those who are blind.

We obviously have more than enough of them already.

It would be much appreciated if you take this into consideration in any future comments.

Sincerely,

Robert

Dear Professor Robert Kowalczyk,

Thank you very much for your suggestion or advice on my second comment. You say, “[W]hat you have written is that it often runs against the spirit of Mrs. Kondo’s story.” However, my comment does not run against Mrs. Kondo’s spirit at all. Rather, I appreciate her courage, sincerity, and noble spirit aspiring peace.

I understand that you are, together with people like Mrs. Kondo, working very hard for peace. I really appreciate your work. I visited Hiroshima. I lived in Nagasaki. Meanwhile I met many hibakushas. What is your real ground to claim that I am against Mrs. Kondo’s spirit?

————

Let me mention two points as follows:

(1) Learning lessons from both sides of the tragedies of the war:

You are focusing on the third paragraph in my comment. It may cause you a misunderstanding if you pick up one part from other related parts of the whole. Please see the second paragraph that is composed of two parts: “Yes” part and “No” part. In the “Yes” part, I wrote, “The more relevant people, such as Mrs. Kondo, speak up, the more the world knows about the tragic effect of the nuclear weapons. (Unfortunately, after more than seventy years, the first generation hibakushas are perishing. The above interview is, thus, very important and precious…)”. In this part, I am appreciating Mrs. Kondo’s courage, sincerity and noble spirit. In the “No” part, I am referring to some political leaders (and indirectly their supporters as well) who seem not to learn from the tragic history, while peace-loving people, including Mrs. Kondo, are warning.

Then, the third paragraph follows the second paragraph. The third paragraph is not independent from other parts of the whole, as mentioned above. This third paragraph is addressed mainly to those who forget or neglect another aspect of the tragedy of WWII in the Asia-Pacific region. It is obvious this part is not against Mrs. Kondo’s noble spirit. While she is offering her sincere interview on a certain tragic aspect of that war, there exists another tragic aspect of that war. Both are tragic aspects, from which everyone of us should learn. I don’t think you claim that we should learn lessons only from one aspect of the tragic history. Or would you claim that to learn only from one aspect of the tragedic war is to run for Mrs.Kondo’s spirit?

(2) Labeling as a non-act for peace:

You label Kate Basco as a sensationalist. Even if she is so, there is a reason for that she said that way. If there is no fire, there is no smoke. Years ago I visited the Philippines and had many opportunities to talk with senior generations of the Filipinos who experienced WWII. Today no one can deny the horrendous war crimes committed by the Japanese military. The atrocities in question were committed by the Japanese military forces, not by citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I clearly wrote that. Is that against Mrs. Kondo’s spirit?

I also wrote, “Nonetheless, if Japanese emphasize their victimized aspect of WWII, and if they do not refer to their offensive aspect of WWII, such attitude will never bring about a genuine and permanent peace to Asia.” From one of the sides of the historic tragedy, people like Mrs. Kondo are offering precious historic lessons. From another side of the historic tragedy, people in the Asian countries are offering (or can offer) another precious lessons. Have you ever met former comfort women, for instance? Have you ever talked with relatives of the victims of Changi in Singapore, for instance? Have you ever interviewed the Japanese Army’s victims or their relatives from Hong Kong, for instance? If you sincerely wish, they will surely offer you their interview(s) filled with precious lessons, as Mrs. Kondo kindly offered through your foundation. If you are in Japan, it might not be very difficult for you to find them and to interview them. Are you ready to interview them, Professor Robert Kowalczyk? Why don’t you learn lessons of the historic tragedies from both sides? If I suggest that we learn from both tragic sides of the Asia-Pacific region of WWII, is that against Mrs. Kondo’s spirit?

You say, “As M.K. Gandhi might comment, you are only adding members to those who are blind. We obviously have more than enough of them already.” These words are another labeling, as you did to Kate Basco (although I have no intention to defend her). You never know if her close relatives were victims of the atrocity committed by the Japanese Army. You have never met her. You know nothing about her personal back ground. Do not judge a person so quickly. The act of labeling without knowing about that person indicates that you are judging her so quickly. The act of labeling does not bring about peace among people. By labeling someone as something, you are directly or indirectly declaring that he or she is your enemy.

The world is filled with the act of labeling. “If you are a Muslim, you are a terrorist.” “If you are questioning about Netanyahu’s government, you are anti-Semitism.” “If you are against the policy of the Trump administration, you are anti-American.” And more. You say, “…which only add more fuel to the kindling fires of hate and distrust which naturally lead to war.” You also say, “As M.K. Gandhi might comment, you are only adding members to those who are blind.” Regardless of how much you are aware of that, your words as such can also be applied to the act of labeling. The act of labeling is everywhere.

All we need and all we wish is “peace among people”, not labeling someone or some people. It is because peace among people is one of the very foundations of “peace among nations”. Did Mrs.Kondo label other people or nation in her interview? No, not at all. She knows what is one of the very foundations of peace.

————

Finally but not least. Thank you very much for sharing Mrs. Kondo’s precious interview with the TMS readers. May her message for peace prevail all over the world! Thank you very much for your peace work through your foundation!

It is still very hot in this summer. Please take care of yourself, Professor Robert Kowalczyk.

Sincerely,

Satoshi Ashikaga

Ashikaga-san’s response to Mr. Kowalczyk’s comment is a bit long for me to read just now. But, his first comment, and the opening of his second comment, do warrant further investigation.

The interview, and Ms. Kondo’s remarks, are shining examples of the best of our humanity. To note some instances of the worst aspects of our “Naked Ape” behaviors, as Mr. Ashikaga does, cannot diminish the qualities that Mr. Kowalczyk’s and Ms. Kondo’s words convey.

I am grateful for the interview, for Mr. Ashikaga’s thoughtful response, and to the TMS site for providing a forum and encouraging such discussions. We live in a very complex world; and with the glut of information and speed of change, it becomes increasingly more so. We can celebrate the virtues of Ms. Kondo and her father, Reverend Tanimoto, the vision of Johan Galtung…and also heed the cautionary warnings and laments of Mr. Ashikaga.

Dear Satoshi,

Thank you for your thoughtful and engaged reply.

My thoughts may be inadequately short.

Well understood are your feelings of pain for the many who have suffered and who are suffering still, on this day, at this precise moment.

Please know that I share your deep sadness and great respect for the victims of humanity’s lack of a higher consciousness; however, the historical numbers are far beyond any itemization or grouping, or any leaning towards a most sincere and warranted reasons for the suffering, including accusations of those who were the perpetrators.

Human history is a continual and continuing record of suffering. This is a fact no one can ignore. It has been carved deeply at great depths in our collective subconscious. If it were not, we would have self-immolated ourselves long before this once-again new day.

Sadly, a great part of your reply has been framed as an accusation of labeling.

Each word we write, or say, or enact is a form of labeling, is it not? Language itself is labeling, what else could it possibly be? Certainly, this is an unfortunate truth, thus the inexpressible.

It appears clear that in 2018, this yet-another year of crises, there is only one valid label worth using, humanity.

We humans are all both purely innocent and gravely guilty. For those who feel more innocent than those considered guilty, there is a strong and natural tendency to point fingers of blame, including at those of both the past and the present who are either invisible or beyond common reach. Thus history continues to repeat itself in an endless unforgiving cycle of blame and effect, World War II being an obvious product of that process.

It is only when we understand that evil is not personal, as it rises from depths found within the best of us, a permanent remnant of our crawl from the sea towards survival and evolution — only then, might we finally understand the essentially blameless innocence of our human existence.

This is also the essence of the interview with Mrs. Koko Kondo, the evolution of human consciousness, of the human spirit. And this is a truth that was never more obviously available to all than at the present moment. Nor one that was more critically needed than now.

With global warming becoming a daily worldwide reality, with insanely-enhanced budgeting for even better nuclear weapons, with a neurotic, profit-seeking mass media eager to join in the search for who was wrong, we grope out in darkness for signs of human evolution.

Whether they appear or not, does not depend on our continuing fixations on past wrongs, whether they be “comfort women,” armies now long dead and gone, rising politicians who just don’t get it, or those who concentrate on speaking out against the now invisible ghosts of the past.

There is all too much need to concentrate on our collective future. Do we really have the time to engage in arguing about who knows more about the horrors of the past? For what true purpose?

I’m sorry to say, Satoshi, but it seems that particular aspect of conflict-transformation has had its day. There simply is not enough time to look back except with a deeper, more human, understanding, which can only be accomplished by tempering our spirits to the critical global tasks at hand.

Mrs. Koko Kondo expressed this very well in her healthy and forward-looking reflections on the past.

Today’s younger generations also instinctively understand this, as I noticed such growing knowledge in years of teaching, especially in recent years.

The young understand very well and are working on it with their eyes on the present and hearts filled with great hopes for their future.

For them, it is an issue of survival.

Perhaps it’s time for us to join them. Or am I wrong?

Robert

Ps. Since I much prefer not to engage in a running dialogue on these pages, you can find my email address at the website linked at the end of my profile. Thank you for your kind understanding.

Dear Robert,

“All people, except myself, are my teachers in one way or another.” – Eiji Yoshikawa

In that sense you are also my teacher, Robert. Thank you for your thoughtful remark!

By the way, today, August 11, was the day more than two decades ago I was assigned to work in the middle of the war zone in Bosnia. Years later after living in Nagasaki, I was working in Bosnia. Who could imagine then? https://www.transcend.org/tms/2015/10/the-sava-river/ What I saw right in front of my eyes, and what I actually experienced then… one day we can talk.

I will contact you in due course.

One again thank you very much, Robert!

Sincerely,

Satoshi

What fine dialogue!…between Professor Kowalczyk and Satoshi Ashikaga. This is what one hopes for when one reads the best websites…but is too often lacking…. They can document their sources, quote from the best, support their views with knowledge and wisdom gained from decades of inquiry and experience. They are models of good behavior and good sense. Thank you, TMS, for encouraging this kind of dialogue and commentary.

Dear Satoshi,

Thank you for your comments and for your finely expressed poem, The River Sava, and also for your Note on your experiences in the Balkans.

I must humbly reply that I myself do not know the realities of war.

The idealism of the late 60’s, particularly that generated by the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, carried my life towards a US Peace Corps experience in universities and government offices of Seoul for three years, starting in 1969. That experience of The Other fueled my desire to work for intercultural and intergenerational understanding, sharing and harmony.

I have lived that life while being nearly oblivious to the cruel and unforgettable realities of war such as you have experienced, except for their aftermaths documented through cultural documentary photography, particularly the images from Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Perhaps this accounts for our different perspectives.

Recently I have been lost in reflection on the deeper effects of PTSD whether from horrific-yet-limited wars such as that of the Balkans or by an immense tragedy of global proportions as was World War II.

Perhaps your passion for expressing the depth of past experiences is a form of catharsis from your own life’s pathways. Only you can provide a reply to that thought.

More generally I have begun to realize that PTSD can be a significant factor in the way that individuals or even nations assess the world; a historically obvious case in point is post-WWI Germany.

The inability for most Japanese to come to grips and face the grand tragedy of not only their country’s devastating adventure into nationalistic expansion but also its totally traumatic ending have essentially left most of them speechless. Voiceless. Even now, 73 years later.

Perhaps it is a continuing effect of national PTSD. I’m far from sure of that theory.

However, within that context among the Japanese, only the Hibakusha have had the true courage and invincible human spirit to express what to others seems inexpressible. And now they too, due to aging and a very subtle mixture of memory loss, glib neglect and accretion into larger, well-known causes, are being both actively and passively silenced into the back pages of collective memory. As if they never existed as witnesses to a highly important fact of our tenuous existence.

This is a potentially devastating loss to the evolution of human consciousness, as expressed eloquently by John Hersey in Hiroshima and other writings.

Perhaps one can view it as yet another inconvenient truth. It is as if the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were mere footnotes and not benchmarks in our awkward yet determined crawl from the dark sea of unknowing, unseeing and unfeeling.

It is for this reason that the current series of articles is being compiled for Transcend Media Service.

In closing, allow me to once again express my sincere appreciation of our dialogue which has reminded me to take note of the benefits of paying attention to the perspectives of others.

There is nothing to be proven except the truth, which itself is intriguingly elusive. However, I believe each of us is heading along different pathways towards the same destination.

Please know that many are still with you. Here on this side of The River Sava.

Sincerely,

Robert

Ps. I look forward to communicating with you via my email address found on the photographic website in my profile. I think it best to end our communicating on TMS as there must be a time limit for responses. If you are based or currently in the Kansai area, perhaps we can meet for a longer face to face discussion.

Dear Robert & Satoshi & Gary & others, greetings.

Just to say, or ask, that you continue your discussion and dialogues here on TMS. Such comments as yours enhance manifold the intrinsic value of the original article–which is the aim: to ventilate ideas, points of view, inform, an so forth. If you privatize your interactions many will be deprived of the benefit of, and perhaps to participate in, a meaningful interchange of ideas, facts, insights as most read but don’t write. Thank you.

I hope you have read Satoshi’s latest piece, sort of a sequel to this discussion: Japanese Emperor’s Remorse and Efforts to Make Amends for His Father’s War (https://www.transcend.org/tms/2018/08/japanese-emperors-remorse-and-efforts-to-make-amends-for-his-fathers-war/)

My two cents as the editor.

With appreciation to you, my friends,

Antonio