Genocide Hoax Tests Ethics of Academic Publishing

INDIGENOUS RIGHTS, HUMAN RIGHTS, AFRICA, ASIA--PACIFIC, EUROPE, LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN, MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA, JUSTICE, PALESTINE ISRAEL GAZA GENOCIDE, HISTORY, ACADEMIA-KNOWLEDGE-SCHOLARSHIP, EDUCATION, LITERATURE, 16 Jul 2018

Reuben Rose-Redwood – The Conversation

Debates over the history of colonialism have sparked controversies on university campuses in recent years, as illustrated by the removal of a statue honoring Cecil Rhodes at the University of Cape Town in 2015.

Desmond Bowles, CC BY-NC-SA

2 Jul 2018 – Hate speech is on the rise. In Canada alone, it increased by a staggering 600 per cent between 2015 and 2016 as part of what some have called “the Trump effect.”

Academia is not immune to this trend. According to a recent study, some scholars have sought to promote “colonial nostalgia and white supremacy” by using the “scholarly veneer” of academic journals to spread “what are otherwise hateful ideologies.” What are the responsibilities of scholars in light of these developments? Are there any ethical limits to what is acceptable for debate in scholarly journals?

To take an extreme example, would an article advocating for genocide be fair game for publication, or is it beyond the ethical bounds of legitimate scholarly debate? That these sort of questions even need to be asked is a testament to the troubling times in which we live.

Recent academic controversies, such as the debate over the “Ethics and Empire” project at Oxford, which seeks to develop a “historically intelligent Christian ethic of empire” in order to justify neo-imperialist interventions in the present, have given a new sense of urgency to addressing the ethics of academic scholarship. Yet when leading historians and other scholars have challenged the legitimacy of such scholarship, the self-proclaimed champions of “free speech” have predictably claimed that academic freedom is under assault.

However, a scholar’s right to free speech does not entitle them to be granted unlimited access to whatever scholarly platform they desire. Scholarly journals have a right to reject any article they decide is unfit for publication — whether due to lack of scholarly merit or on ethical grounds.

The scholarly community also has a right to question the judgement of academic journal editors if they believe that a published article does not meet the basic standards of academic conduct.

This was precisely the situation that arose last year when a prominent international studies journal published an article praising the virtues of colonialism while ignoring the atrocities of colonial rule.

The “case for colonialism” debacle

When the Third World Quarterly published Bruce Gilley’s “The Case for Colonialism” last fall, it sparked outrage within the scholarly community. Not only did the article proclaim that colonialism was “beneficial” to the colonized, but it also advocated for the recolonization of former colonies by the Western powers.

Read more: Colonialism was a disaster and the facts prove it

In response, two petitions garnered over 18,000 signatures calling for the article’s retraction. The petitions argued that the article should never have been published since its account of the history of colonialism was deeply flawed and its recolonization proposal would violate the basic human rights of millions.

The publisher, Taylor & Francis, eventually withdrew the article. Yet they did so not for the reasons laid out in the petitions, but allegedly due to threats of violence against the journal’s editor. To date, the publisher has not released any concrete evidence related to these threats, nor have they explained whether a criminal investigation was conducted into the matter.

Although the petitioners welcomed the news of the article’s retraction, both critics and supporters of the Third World Quarterly viewed the publisher’s rationale for withdrawing the article due to violent threats — rather than a lack of scholarly merit — as setting a dangerous precedent.

However, the article was recently republished by the National Association of Scholars, a conservative advocacy group, in the name of supporting “academic freedom.”

Supporters of the Third World Quarterly had made much the same argument in a petition published in The Times last December, which stated that academic journal editors have a right “to publish any work — however controversial — that, in their view, merits exposure and debate.”

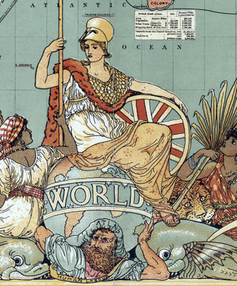

European colonialism was based upon the establishment of racial hierarchies that subjugated colonized peoples to European control.

Walter Crane/Boston Public Library

Ethics and academic freedom

What exactly “merits exposure and debate” in scholarly journals? As the editor of a scholarly journal myself, I am a strong supporter of academic freedom. But journal editors also have a responsibility to uphold the highest standards of academic quality and the ethical integrity of scholarly publications.

When I looked into the pro-Third World Quarterly petition in more detail, I noticed that over a dozen signatories were themselves editors of scholarly journals. Did they truly believe that “any work — however controversial” should be published in their own journals in the name of academic freedom?

If they had no qualms with publishing a case for colonialism, would they likewise have no ethical concerns about publishing a work advocating a case for genocide?

The genocide hoax

In late October 2017, I sent a hoax proposal for a special issue on “The Costs and Benefits of Genocide: Towards a Balanced Debate” to 13 journal editors who had signed the petition supporting the publication of “The Case for Colonialism.”

In it, I mimicked the colonialism article’s argument by writing:

“There is a longstanding orthodoxy that only emphasizes the negative dimensions of genocide and ethnic cleansing, ignoring the fact that there may also be benefits — however controversial — associated with these political practices, and that, in some cases, the benefits may even outweigh the costs.”

As I awaited the journal editors’ responses, I wondered whether such an outrageous proposal would garner any support from editors who claimed to support the publication of controversial works in scholarly journals.

Would they think that a case for genocide “merits exposure and debate,” or would any of the editors raise ethical concerns about its content?

As it turns out, nine of the editors declined to move forward with my proposal and the remaining four never responded. This seemed to be a reassuring sign that there were still ethical standards at work in the editorial decision-making process. However, the reasons for their rejections differed markedly, and very little had anything to do with scholarly ethics.

The editors’ responses

Two editors noted that their journals rarely if ever accept special issue proposals, while two others explained that the topic of genocide didn’t align with the focus of their journal. Interestingly, several editors expressed skepticism about whether there was a need for “balanced” debate on the topic.

More concerning were those who declined the hoax proposal but praised it nonetheless. For instance, one editor noted that the proposal “sounds fascinating.” Another offered encouraging advice and even stated that “I hope you do find an outlet.”

Of all the responses to the hoax, only one editor raised any major ethical concerns about the nature of the proposal itself.

Referring to the submission as “morally repugnant” and “offensive,” the editor said it was simply unthinkable to imagine that such a proposal could even have been submitted for consideration to a scholarly journal.

Here was a forceful defense of the ethical integrity of academic publishing if ever there was one. Yet why had this very same editor supported the publication of “The Case for Colonialism,” especially given the historical linkages between colonialism and genocide?

The ethical limits of scholarly debate

When a journalist brought the comparison between colonialism and genocide to the attention of Bruce Gilley, author of “The Case for Colonialism,” Gilley made a very revealing comment. He said that:

“It’s an absurd analogy. Genocide, I think everyone would agree, is a moral wrong. There’s absolutely no plausible philosophical argument that one group of people establishing authority over another is an inherent moral wrong. Human history is all about alien rule.”

This statement is remarkable in a number of ways. For starters, it ignores the fact that a basic principle of international law is that the “subjection of peoples to alien subjugation, domination and exploitation constitutes a denial of fundamental human rights.”

Colonialism violates the right to self-determination as established by UN Resolution 1514(XV), 14 December 1960. Patrick Gruban/Flickr

It also obscures the undeniable historical connections between colonialism and genocide. And, lastly, it is a tacit acknowledgement that an academic work which promotes a “case for genocide” is indeed beyond the bounds of legitimate scholarly debate on ethical grounds.

All the blustering rhetoric of academic freedom notwithstanding, it seems there is, in fact, general agreement that scholars must have at least some sort of ethical limits to academic debate. The key point of contention is where exactly those lines should be drawn. Gilley and his supporters would have us believe that making a case for colonial domination is well within those limits.

As for my part, I’ll stand with the more than 18,000 scholars who have argued that if an academic work is calling for the violation of basic human rights and fundamental freedoms, that’s a pretty good indication it doesn’t deserve the time of day from reputable scholarly publishers.

_________________________________________

Reuben Rose-Redwood – Associate Professor, University of Victoria

Reuben Rose-Redwood – Associate Professor, University of Victoria

Republish The Conversation articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons license.

Go to Original – theconversation.com

DISCLAIMER: The statements, views and opinions expressed in pieces republished here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of TMS. In accordance with title 17 U.S.C. section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. TMS has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is TMS endorsed or sponsored by the originator. “GO TO ORIGINAL” links are provided as a convenience to our readers and allow for verification of authenticity. However, as originating pages are often updated by their originating host sites, the versions posted may not match the versions our readers view when clicking the “GO TO ORIGINAL” links. This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

2 Responses to “Genocide Hoax Tests Ethics of Academic Publishing”

Read more

Click here to go to the current weekly digest or pick another article:

INDIGENOUS RIGHTS:

- We Must Purge Genocide from the Marrow of Our Bones

- The Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples

- ‘A World without Borders’: Revolutionary Love and Solidarity for Palestine

HUMAN RIGHTS:

- US “Relocates” Iraqi Refugee to Rwanda via New Diplomatic Arrangement

- How the Human Rights Industry Manufactures Consent for “Regime Change”

- Genocide Emergency: Gaza and the West Bank 2024

AFRICA:

- How the International Monetary Fund Underdevelops Africa

- How Trump’s Embrace of Afrikaner “Refugees” Became a Joke in South Africa

- New Study Reveals Changing Attitudes to Female Genital Mutilation among Sudanese Communities in Egypt

ASIA--PACIFIC:

- Nepal: Proto-Nationalism Entrapped in the Musical Chair Circle of Political Parties and Floundering Economy

- South Korea's Biosecurity Is Safe, Thanks to Russia

- India and Pakistan: Freedom Lost but Animosity Flourishes

EUROPE:

- Raised in a Colonial Death Cult: 600 Years of KU Leuven and still...

- The Rise of ‘Antidiplomacy’ in a Powerless Europe

- ‘Diplomatic Tsunami’ Nears as Europe Begins to Act against Israel’s ‘Complete Madness’ in Gaza

LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN:

- China Must Provide More Substantial Aid to Cuba

- Trump's Utterly Cruel and Inhuman Immigration Policy Targetting Haitians

- Venezuela: Pro-Government Alliance Wins Big in Legislative and Regional Elections

MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA:

- Persia, Iran, and the Great Arab Mix-up: A Sarcastic Stroll through History to Today’s Messy War

- Will Israel Continue to Attack Iran until the International Community Approves the Eradication of Palestine?

- Crusade against Iran and the Complicity of Western Decadent Civilizations

JUSTICE:

- Gaza Tribunal Project: Opening Remarks

- The Sarajevo Declaration of the Gaza Tribunal (28 May 2025)

- Gaza Tribunal: Program for Sarajevo Public Sessions, 26-29 May 2025

PALESTINE ISRAEL GAZA GENOCIDE:

- Signing and Spreading the Sarajevo Declaration of the Gaza People's Tribunal

- Israeli Soldiers Ordered to Shoot at Unarmed Palestinians Waiting for Aid: Report

- Gaza’s Hunger Games

HISTORY:

- History of US-Iran Relations: From the 1953 Regime Change to Trump Strikes

- Digging Up the Roots of Human Culture

- The Geopolitics of Southeast Europe and the Importance of the Regional Geostrategic Position at the Turn of the 20th Century

ACADEMIA-KNOWLEDGE-SCHOLARSHIP:

- Academia at the Crossroads: Indoctrination, Systemic Violence, and the Security Risks of Rentier Capitalism

- The Futility of Genocide Studies after Gaza

- Are We as Area Studies Scholars Guilty of Negligence in Allowing Genocides to Happen in the Regions We Study?

EDUCATION:

- Misconception and Right Concept of Peace Education: Theory and Praxis

- Financing Higher Education to Build Non-exploitative Society for Peace

- Relevance of Peace Education

LITERATURE:

I have numerous questions in relation to this argument. It makes an easy assumption that colonialism is obviously reprehensible, which may be valid for some at this time, but certainly has not been valid in the past, nor with respect to neo-colonialism, nor presumably with respect to projects for colonialising planets elsewhere (as explored by the movie Avatar). It is not sensitive to the manner in which humans continue to abusively colonise wilderness areas.

As in any court case, there are merits to articulating an argument from both sides, rather than assuming that those indicted are necessarily and automatically guilty (Saddam Hussein, Osama bin Laden, etc). Even Eichmann had his day in court. Should he have been executed without trial because adequate proof of his guilt had already been assembled according to some? Would the world have learned anything from Hussein or bin Laden if they had had a trial?

There is a different argument to be made with respect to potentially reprehensible strategies — such as use of nuclear weapons, scientific whaling, geoengineering. There is a degree of value in arguing for the reverse of genocide as I have done — tongue in cheek — namely to use genetic engineering and the like to enable very large families, maybe 20 or 40 children per mother, which I happen to consider completely irresponsible but which some would value:

Enabling Fruitful Multiplication of Global Population

Eliciting massive social consensus by unconstrained reframing of strategic priorities

https://www.laetusinpraesens.org/docs10s/repop.php

And what about the arguments for just war theory in which the religions have been so complicit, or “just torture theory” in which Western governments have been so complicit, or maybe even “just sacrifice theory” which seems to frame so many strategies advocated at this time?

now my head hurts